In a hybridised overview and an interview with assistant curator Thomas Sutton, Elephant writer Katrina Nzegwu explores Tavares Strachan’s There is Light Somewhere at the Hayward Gallery.

Kingston, Jamaica, 1914. Political activist Marcus Garvey establishes the UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association) in advocacy for economic and political self-determination of Black bodies across the globe – for the unity between Africans and the African diaspora; the dismantling of European colonial rule in Africa in favour of continental political unification; and the propulsion of black empowerment through separatism. In the following decades his writings would consolidate as the eponymous movement of Garveyism; substantiating the theories of Black nationalism and Pan-Africanism.

New York, USA, 1964. Incendiary poet, prophet and prose-master James Baldwin pens a series of four essays for the monograph produced in collaboration with his childhood friend and photographer Richard Avedon – Nothing Personal. A singular embodiment of the heartbreaking and magnificent multiplicity of the American experience, amidst the final of the collection’s prose-elucidations is Baldwin’s evocation: “One discovers the light in darkness, that is what darkness is for; but everything in our lives depends on how we bear the light. It is necessary, while in darkness, to know that there is a light somewhere, to know that in oneself, waiting to be found, there is a light.”

London, United Kingdom, 2024. A monumental bronze visage of Garvey – Ruin of A Giant (Marcus Garvey) (2023) – and the words of Baldwin find communion as the heralds of Tavares Strachans’ solo exhibition at the Southbank Centre’s Hayward Gallery: There is Light Somewhere. Exemplary of Strachan’s proclivity for, and profound ability to illuminate the lives and stories that societal structures historically strive to relegate to the dark margins; Strachan’s first mid-career survey constitutes a living history of the diasporic subjectivities that have both structured his thinking, and paved the way for the uplifting of Black and Brown persons worldwide. Indeed, the exhibition’s introductory wall text features a quote by Strachan: “Art can be a tool for us to investigate a sense of belonging, but if you don’t understand these hidden histories, then you don’t understand where you fit into the full picture.”

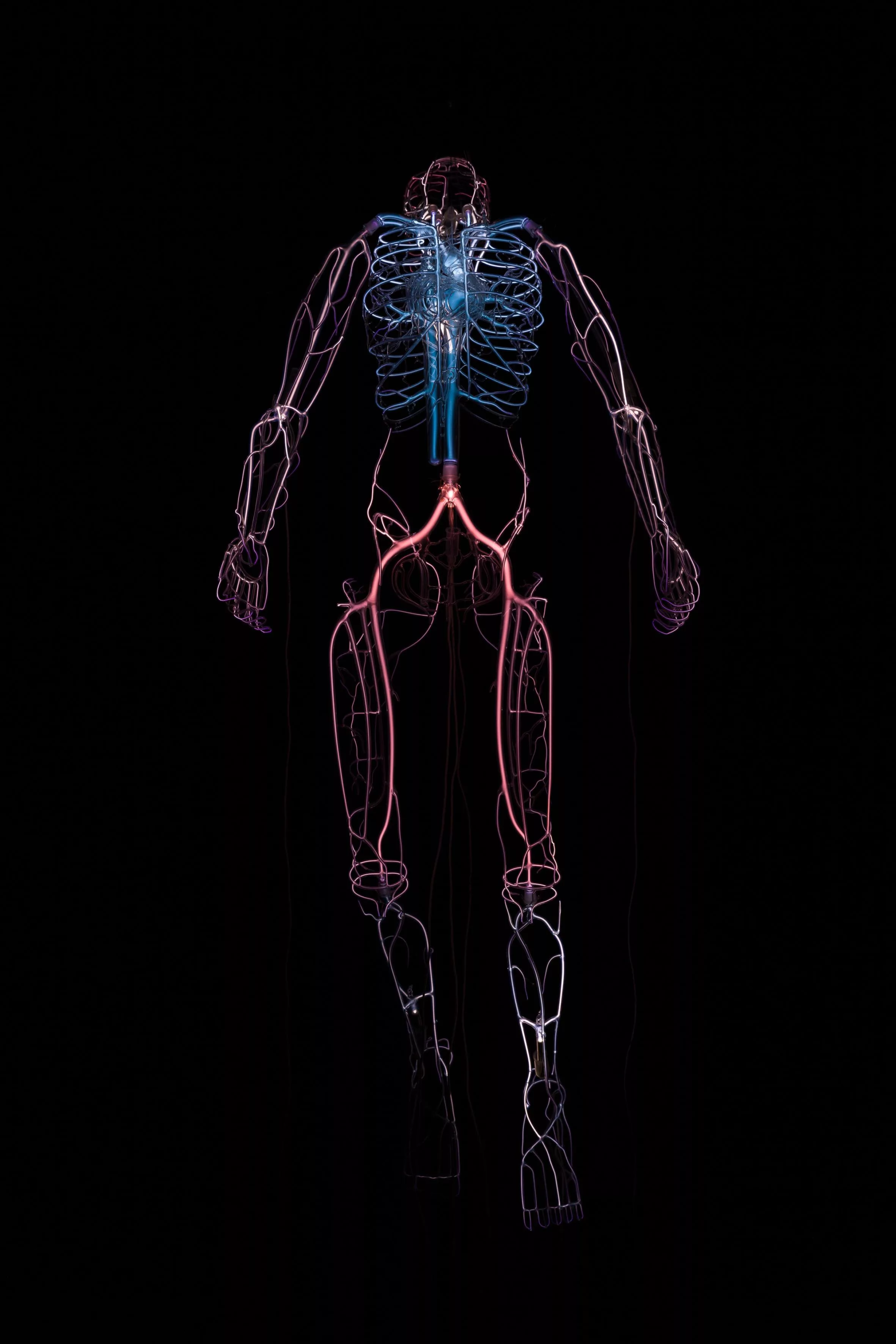

Born in Nassau, Bahamas, and living and working in New York City, Strachan’s enticingly undefinable practice oscillates between the somatic and scientific; macro and micro – at once personal and collective; ceaselessly informative in a manner that evades pedantry. Technology is deployed to the end of aesthetic stimulation, for instance in the work Henrietta (2014). A rendering of Henrietta Lack – the study of whose unusual cancer cells were deployed (without her consent or awareness) has profoundly propelled diverse aspects of medical research – in pyrex and mineral oil utilises the shared refractive index of the materials to construct an image variously perceivable at different angles; paying heed to the interplay of presence and absence that permeates, perhaps even characterises Strachan’s practice.

Flipping exploration as the remit of the white middle and upper classes on its head, various works by Strachan demonstrate his forays into the vagaries of space-time, as a route to the creation of an alternative future. Foregrounded in the works ENOCH (Display Unit) (2015-17) and Robert (20180, are the story of Robert Henry Lawrence Junior: the first African American astronaut to be selected for a national space programme. As Lawrence Junior was a pioneer, so too is Strachan – launched into the stratosphere via a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in 2018, ENOCH as hybrid sculpture-satellite orbited the earth for three years; re-entering on December 21, 2021.

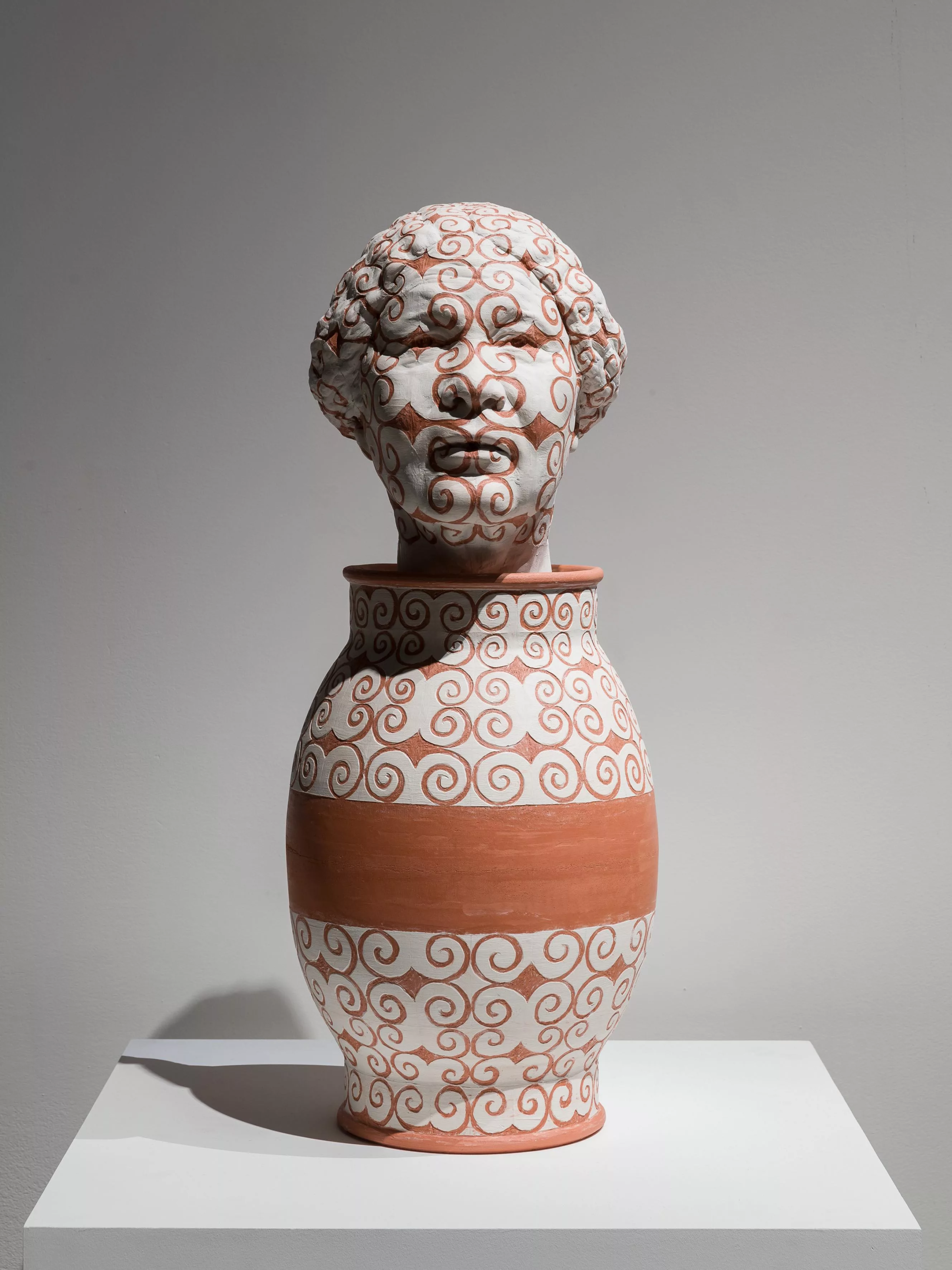

Colonialism and commerce; art history and activism come into play via series of visages cast in multiple media: from Nina Simone bearing a golden coronet emerging from a ceramic clamshell in Inner Elder (Nina Simone as Queen of Sheba) (2023); to A Map of the Crown (2024). A constellation of seven bronze busts bringing together the construction of Greco Classical figurative sculptures, with the intricacy of correlate traditions in the West African kingdom of Benin; each sculpture is adorned with with different African and Afro-Caribbean coiffures woven from hair collected from Bahamian barbershops.

The compelling thread of the exhibition is the notion of narratives as, in the words of Strachan, “The connective tissue of the human experience.” Further stories illuminated include those of W.E.B. Du Bois, Hailie Selassie and Mary J. Seacole; Frankie Paul, Marsha P. Johnson, Steve Biko and King Tubby. In a riot of cultural references, materials, sensory experiences and philosophical probings, the presence of large-scale collage works bring covers of JET magazine, flamingoes, and Spalding-branded basketballs; into conversation with the legacies of Queen Elizabeth II, assassinated US president John F. Kennedy, and Benin-born critic of French colonialism Tovalou Houénou. Though rooted in the exploration of the Black diasporic experience (as pertains to Strachan’s own biography), the exhibition’s message of belonging and knowledges is metonymic for the cultural and experiential cumulation, amalgamation and interconnection, inherent to the existence of all members of historically marginalised communities. On the occasion of the show’s opening; and in advance of the inauguration of the show’s accompanying public programme You Belong Here; I had the fortune of walking through Strachan’s unique and captivating practice with the show’s Assistant Curator, Thomas Sutton.

Katrina Nzegwu: I wanted to ask about the title of the exhibition – whether that was an artistic, or curatorial decision?

Thomas Sutton: The title of the exhibition is inspired by a quote from James Baldwin, the writer, essayist and social critic. We have an artwork in [the opening galleries of] the exhibition which is a neon text version of the passage from which the title is taken,and that also has a sound element; where the artist and others reading that passage of text is cycled and repeated in the opening galleries.

It was the artist’s decision, and one that was come to in dialogue with the curators; but it really signifies various things. The idea of light, and the idea of making things visible is a really important theme in the exhibition. What Tavares Strachan is particularly interested in, and what we’ve foregrounded in this show, is visibility versus invisibility. Those who are seen versus those who are not – the idea of carrying light is symbolic of that.

KN: As the title and its conceptual essence pertains to the wider cultural programme across the summer, You Belong Here – could you speak a bit more about this exhibition as a jumping off point?

TS: Tavares’ artwork You Belong Here (2014) – the large scale neon text piece on the side of the Hayward Gallery – that phrase has lent its name to the wider programme at the Southbank Centre. Obviously for an art centre that is constantly trying to be as inclusive and as welcoming as it possibly can, that’s a wonderful slogan for us, and a wonderful phrase for us to be able to share with our audiences. But the way that Tavares is using it actually has a bit of a sting in the tail. The way Tavares speaks about that piece,he says that, actually, if you have to be told that “you belong here” – what does that raise? What does that perhaps point to – some tension or some feeling of not belonging; or some contrast between those who really get to feel comfortable in a space and those who don’t.

Whilst it’s an affirmative statement, for Tavares it’s also a probing. And I think other works we have in the show – for instance those relating to Marcus Garvey – the Black Star Liner Ship, a 40-foot installation we have visible on the terrace alongside this slogan You Belong Here – I think those two works make a wonderful pair. Garvey was very much interested in the idea of belonging, and really exploring the racial divides that existed in America in the first half of the 20th century. To put those two works in conversation amplifies the critical voice of that statement, as well as its affirmative feeling.

KN: Why Marcus Garvey outside the exhibition in particular – as opposed to any of the other larger bronze sculptures in the Ruin of a Giant series – Harriet Tubman, or King Tubby, for instance?

Marcus Garvey is an absolutely uniquely important figure for Tavares. Part of Tavares particular interest is in the stories that aren’t told through our dominant historical narratives; he describes how, growing up in the Bahamas, he didn’t learn about Marcus Garvey in his school classes. He wasn’t represented in that context; Tavares learnt about Garvey through music – through Burning Spear. That was his route into this extraordinary story about social activism; about campaigning towards social self determination, and the Black Star Line – a black owned business that was about commerce, but also about promoting a greater feeling of belonging.

Garvey is a figure who was hugely active in American activism, he was hugely active in London – in fact he died in London – and he started an organisation, the UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association), that had [over 11] million members in 40 countries [by 1926]. He had this extraordinary reach and extraordinary ambition as an activist; but he’s also this icon to the Rastafarian movement – a prophet within that religion, and someone who is central to the musical culture, as well, of the Caribbean. He’s a figure that sits between different areas of culture and politics, and a unique touchstone that Tavares particularly wanted to celebrate and amplify.

KN: With Garvey, but also with the wealth of cultural references – particularly in the collage works – there’s this thread of Pan Africanism. I was wondering how that fits with, or is situated in relation to the decision to have this first mid-career survey in London; as opposed to in New York or the Bahamas?

TS: I think in a way the only thing I can say is that we’re very fortunate to have that opportunity to show Tavares’ work at the Hayward. Ralph Rugoff, the curator of this exhibition, showed Tavares’ work in his Biennale in Venice a few years ago;and they’ve had a relationship, a dialogue for some time. Whilst I think there are many different contexts in which Tavares could have had a big museum presentation, really it’s our good fortune that it is in London.

KN: I wanted to ask about the relationship of this show to the previous one – When Forms Come Alive, 7 February–6 May 2024 – and this thread of work at the intersection of technology, the digital, and the scientific. With Tavares’ own relationship to exploration, and When Forms…survey of dynamism and transformation – how do these things then come into conversation with the somatic, or with cultural conversations?

TS: What both exhibitions might share, and what other exhibitions in the Hayward programme might share, perhaps, is that they’re looking at art that is pushing boundaries. They’re looking at art that sits between certain areas, and reaches beyond the bounds that art traditionally occupies – that’s certainly true with Tavares’ work. From the beginning he was undertaking artistic projects which really were difficult to categorise in a traditional way. Visiting the arctic, or undergoing space cosmonaut training in Russia…Tavares has always said that he makes art at the interstitial points between disciplines. Whether that’s exploration or science or technology; the idea of putting a sculpture into space through a collaboration with Space X; or the idea of making invisible sculptures which rely on the physical properties of pyrex glass mineral oil.

There’s technology and there’s science embedded into what Tavares is doing; but then there’s also – and you’ve referred to it – there’s the joy of images. Placing images into conversation with one another to create new meanings…and also a joy in material. You have an amazing range of materials in this exhibition. From ceramics, to bronze, to painting, to neon works; photography, large scale installation, sonic pieces. There’s an excitement at making art in all sorts of different mediums, as well, as you say, in pushing the boundaries into different areas and disciplines. There is Light… as a show has huge breadth and variety. Its reflective of Tavares extraordinary practice, which is hugely broad; and, in a way, refuses to respect the boundaries. Transgressing boundaries, refusing the status quo…it seems to me that that’s what Tavares’ projects have been about since the very beginning, when he opened an encyclopaedia and said hang on a minute – “Who gets to write these stories, who gets to choose these entries? I’ll make my own encyclopaedia.” Tavares is quite unique like that.

KN: Could you talk about the decision to curate the show in these three thematic sections, as opposed to a more classical chronological survey?

TS: When we were planning the exhibition, we considered different options in respect to that. Ultimately the show is the way it is, because of the encyclopaedia project – Tavares calls it the spine of the exhibition. Giving visitors the opportunity to engage with that incredibly rich, knowledge and information based project – the idea of exploring across time and space through knowledge – that seemed like the crucible of the exhibition.

From there we could look at Tavares exploration projects, where he’s gone on these incredible physical journeys; this is the second strand of the exhibition. And then this idea of remapping as the [third strand]; works that are particularly looking to the African continent through all sorts of different cultural references, whether that’s through hairdressing, or through architecture. We have an installation based on a traditional thatched installation inspired by Tavares’ trip to Uganda; and then, as you mention, Pan Africanism – the Back-to-Africa movement that people like Marcus Garvey were proponents of. And in a way, that strand represents some of Tavares’ more recent works, the installations such as Intergalactic Palace (2024), that people will see last in the exhibition.

The encyclopaedia seemed like the appropriate entry and access point for people coming to Tavares’ work anew. It really gives you a first glimpse into his extraordinarily curious mind; his desire to explore, and to go beyond the bounds of what has been permitted or what is laid down.

Written by Katrina Nzegwu

Tavares Strachan’s There is Light Somewhere is on view at the Hayward Gallery until 1 September

find out more