This feature originally appeared in Issue 31.

Now that I look back, I realize I already had the potential to be a fujoshi when I was still in elementary school. Fujoshi means “rotten girls”, and is the self-deprecatingly humorous term used by female readers of “Boys’ Love” manga to describe themselves. Back then, in the Eighties, I was living in Bayside, New York, and on Saturdays, after Japanese school in Flushing, we would drop by the Japanese market, Daido, to shop for groceries. While I waited for my parents, I would go into the corner dedicated to books and become absorbed in a world imported from my home country. I can’t imagine how they miraculously made it into the limited Daido selection, but almost all the volumes from Keiko Takemiya’s Kaze to Ki no Uta (The Poetry of the Wind and the Trees, 1976), Mineo Maya’s Patalliro (1978) and Moto Hagio’s Thomas no Shinzo (Thomas’s Heart, 1974)—all classics of shonenai (“love among beautiful boys”) manga—were present. And so it was that I would read these works, stocked alongside more mainstream fare such as Doraemon, Dr Slump and Candy Candy, never questioning the same-sex male relationships depicted in them and even experiencing a strange feeling of attraction to the characters.

Fast-forward to when I became a college student in Hyogo, Japan. I used to visit a local secondhand bookstore with my sister to dig up interesting finds, and I came across Zetsuai (Absolute Love, 1989) by Minami Ozaki. Set in Japan’s bubble economy of 1986–91, the love affair between the obsessive seme (the dominant partner in a BL homosexual relationship) and the beautiful but traumatized uke (the passive partner) fascinated me. It wasn’t long before I then found myself hooked on a story about the relationship between a superstar musician named Koji and a genius soccer player called Takuto. At the time the term “Boys’ Love” (or just BL as it’s now commonly known) didn’t even exist, and soon after I left Japan again and moved on to other reading matter. Little did I know that BL culture was growing rapidly, with derivative works (doujinshi or self-published fanfiction) at the root of this expansion, and that by 1995 more than thirty BL magazines would be in production.

Fast-forward again to spring 2013. Now, almost thirty years after my first encounter with shonenai, one of my friends casually hands me a copy of Setona Mizushiro’s Kyuso wa Chiizu no Yume o Miru (The Cornered Mouse Dreams of Cheese), claiming it to be her favourite manga—and in the process reintroducing me to the richest and most diverse form of popular entertainment in Japan today. It was as if I had been struck by lightning. It had taken me three decades and I had certainly gone the long way round, but somehow I was now able to officially enter the land of BL. That my awakening came so late may also have been my good fortune, since the genre had matured considerably and many high-quality works had been produced in the previous twenty years, leaving me able to choose from the pick of the crop. I felt like I had stumbled upon a goldmine—a rare experience in this day and age, when everything has already been done, discovered and consumed.

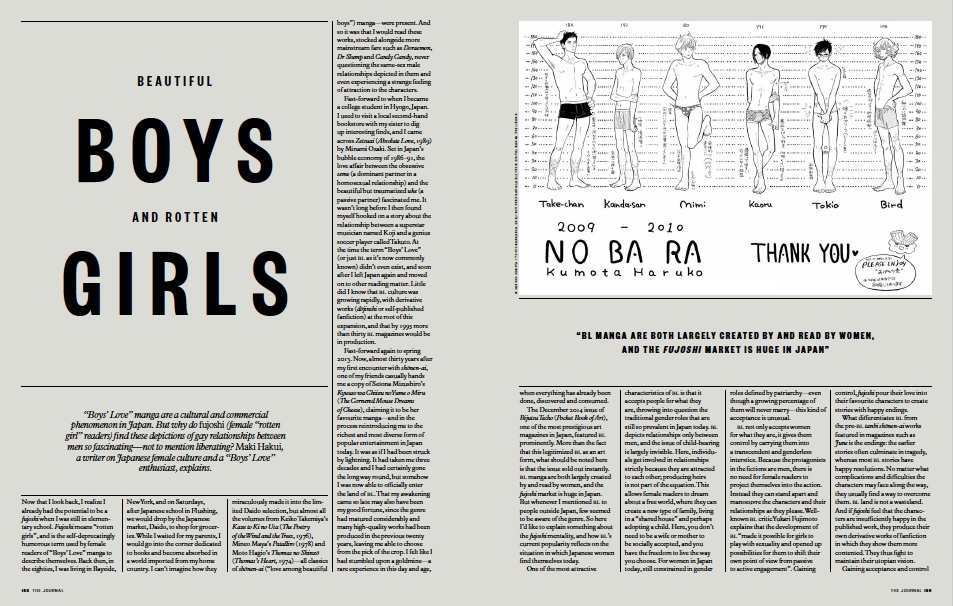

The December 2014 issue of Bijutsu Techo (Pocket Book of Art), one of the most prestigious art magazines in Japan, featured BL prominently. More than the fact that this legitimized BL as an art form, what should be noted here is that the issue sold out instantly. BL manga are both largely created by and read by women, and the fujoshi market is huge in Japan. But whenever I mentioned BL to people outside Japan, few seemed to be aware of the genre. So here I’d like to explain something about the fujoshi mentality, and how BL’s current popularity reflects on the situation in which Japanese women find themselves today.

One of the most attractive characteristics of BL is that it accepts people for what they are, throwing into question the traditional gender roles that are still so prevalent in Japan today. BL depicts relationships only between men, and the issue of child-bearing is largely invisible. Here, individuals get involved in relationships strictly because they are attracted to each other; producing heirs is not part of the equation. This allows female readers to dream about a free world, where they can create a new type of family, living in a “shared house” and perhaps adopting a child. Here, you don’t need to be a wife or mother to be socially accepted, and you have the freedom to live the way you choose. For women in Japan today, still constrained in gender roles defined by patriarchy—even though a growing percentage of them will never marry—this kind of acceptance is unusual.

BL not only accepts women for what they are, it gives them control and carrying them into a transcendent and genderless interstice. Because the protagonists in the fictions are men, there is no need for female readers to project themselves into the action. Instead they can stand apart and manoeuvre the characters and their relationships as they please. Well-known BL critic Yukari Fujimoto explains that the development of BL “made it possible for girls to play with sexuality and opened up possibilities for them to shift their own point of view from passive to active engagement”. Gaining control, fujoshi pour their love into their favourite characters to create stories with happy endings.

What differentiates BL from the pre-BL tanbi shonenai works featured in magazines such as June is the endings: the earlier stories often culminate in tragedy, whereas most BL stories have happy resolutions. No matter what complications and difficulties the characters may face along the way, they usually find a way to overcome them. BL land is not a wasteland. And if fujoshi feel that the characters are insufficiently happy in the published work, they produce their own derivative works of fanfiction in which they show them more contented. They thus fight to maintain their utopian vision.

Gaining acceptance and control in this way, fujoshi turn into philosophers seeking the answer to the big questions: “What is love? What is desire? Who are we?”

BL can certainly be generic but the details within the broader storytelling and character-defining rules are constantly being renewed. And BL is all about the details. Log on to the BL website Chiru Chiru and look at the range of search-engine keywords for the different types of seme—oresama (bossy), kichiku (brutal), kenage (lovable), shuchaku (obsessive), hetare (loser)—and uke—tsundere (cold but sweet), inran (slut), wanko (royal like a dog), futanari (androgynous), kinniku (muscular), etc. Moreover, the average BL spends twice—or ten times—as many pages describing a key moment in a relationship as a regular manga.

BL contains a lot of explicit depictions of sex, and many people just see it as pornography, but it’s the nature of desire that fujoshi are interested in. Having two men engage in many different kinds of sex, and depicting those acts in detail, is a highly intellectual philosophical play. What is important in BL is the relationship between the main characters and the nature of the obsessions they show for each other: naked souls crashing into each other. It’s this process that fujoshi want to see more than the act of sex. “What is important is desire, not sex itself,” as Marguerite Duras put it in La Passion Suspendue (1989). “I already knew when I was a child that the universe of sexuality was fascinating, a world far beyond what one can imagine. My life has been a process to verify that fact.”

Rihito Takarai’s Ten Count depicts an intense relationship between a secretary with a morbid cleanliness obsession, Shirotani, and a therapist who tries to cure him of his condition, Kurose. The artist uses her delicate skills to portray both the sexual and psychological engagement of the two characters to carry readers into their closed world of “therapy”. Shirotani has had a traumatic experience in the past but Kurose’s obsession with his patient hints at problems of his own. The mystery of the men’s difficulties and their hidden causes, not to mention the drama of their relationship—Shirotani’s not wanting/wanting to be touched, Kurose’s wanting/not being able to touch—provide all the materials necessary for a psychological masterpiece.

Then there’s Setona Mizushiro’s aforementioned Kyuso wa Chiizu no Yume o Miru and Sojou no Koi wa Nido Haneru (The Carp on the Chopping Board Jumps Twice), parts one and two of the same story, which Keiko Takemiya hailed as one of the great works of BL. It’s a story about a straight thirty-year-old “salary man”, Kyoichi, who is indecisive and can’t say no to anyone who shows him affection, and a gay private investigator, Imagase, who has been in love with Kyoichi ever since they were students together. Imagase is anxious that Kyoichi will go back to being straight, while Kyoichi, on the other hand, fears that because he does not consider himself genuinely gay, he won’t be able to make Imagase happy. The pair’s paranoia makes for high drama and opens an investigation into the meaning of love and, indeed, of personal identity and authenticity.

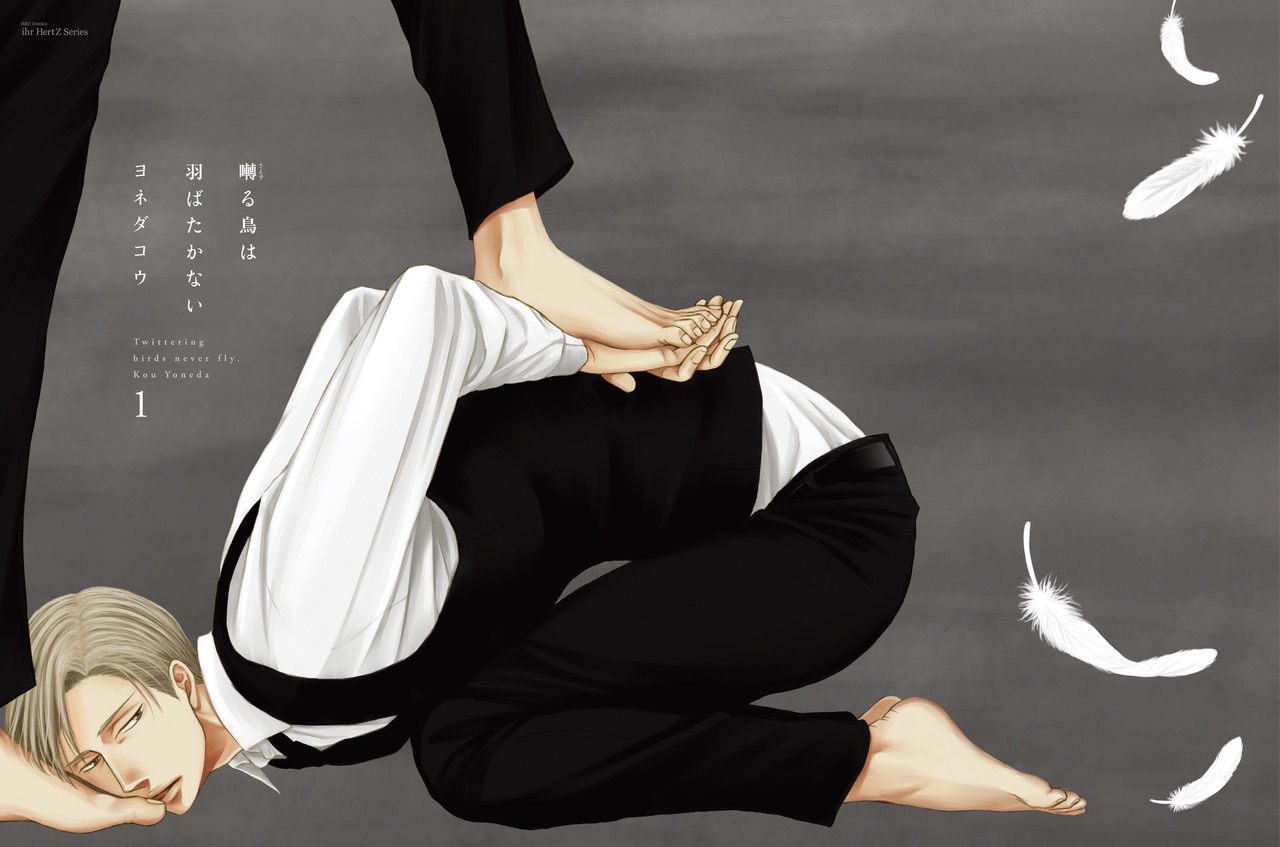

Kou Yoneda’s Saezuru Tori wa Habatakanai (Twittering Birds Never Fly), which is currently being raved about by fujoshi as a kami (godly) work, is a hardboiled yakuza BL about a young yakuza head, Yashiro, a perverted but compellingly cool masochist, and his impotent bodyguard, Domeki. Despite the violence of their surroundings, Yoneda’s characters are full of pathos and marked by personal traumas; readers are immediately drawn into the emptiness and sadness of their existences. Yashiro is particularly brilliantly drawn, and his twisted and contradictory nature keeps readers on tenterhooks as to where his relationship with Domeki will go next.

In their hungry search, as Mark McLelland and James Welker explain in Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan (2015), fujoshi have “come to view all of culture through their ‘rotten filters,’ constantly on the lookout for homoerotic interpretations of otherwise everyday situations and events. In their radical reimagining of the potentialities of affection between men, Japan’s rotten girls avant la lettre have opened up new spaces for the exploration of masculinity and femininity for men and women alike.” When you discover it, this “rotten filter” can turn your black-and-white world into a high-definition movie.

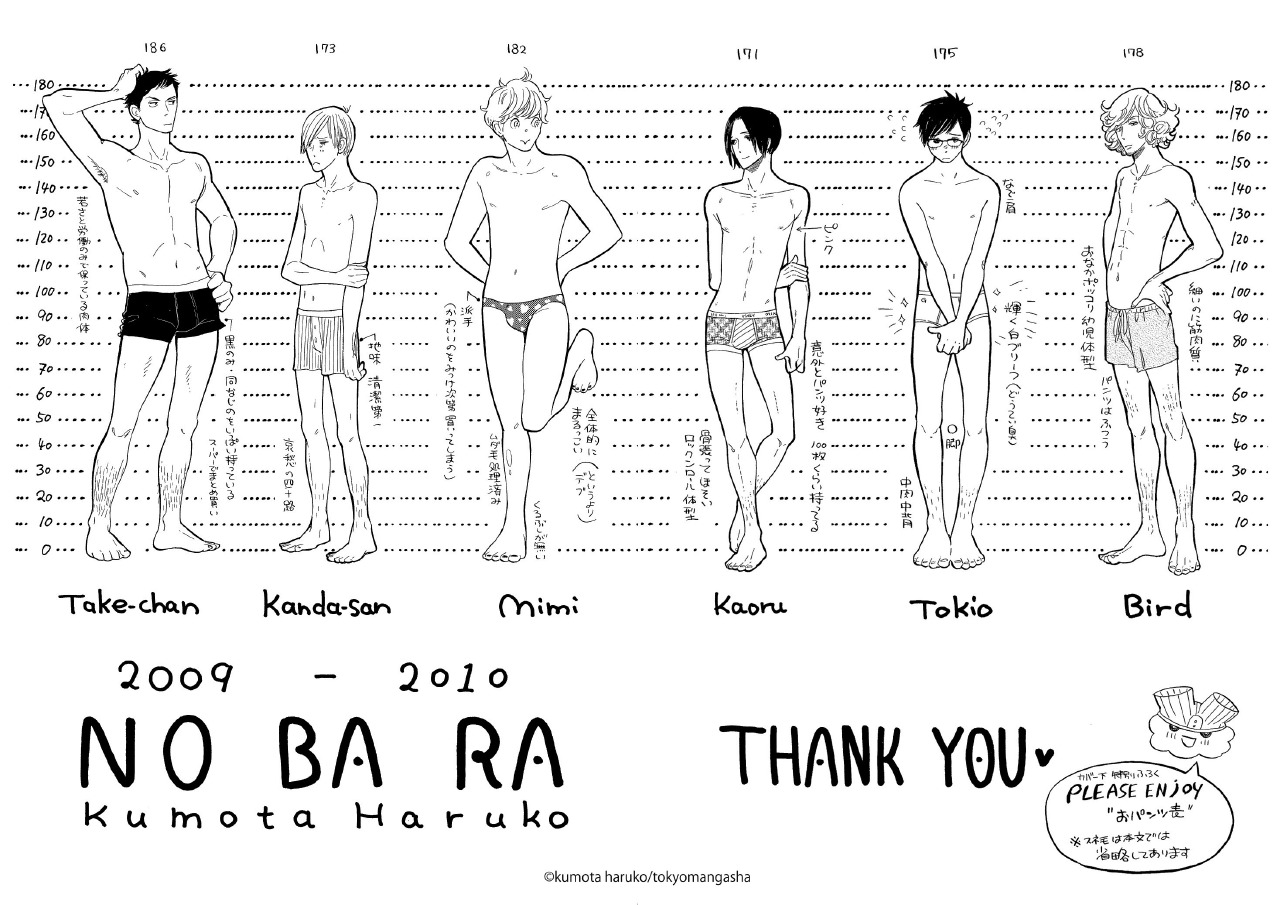

It’s worth noting the success many BL manga creators have also achieved in the cultural mainstream. Works by mangaka such as Haruko Kumota, Fumi Yoshinaga, Setona Mizushiro, Tomoko Yamashita and Est Em are now being enjoyed by the widest possible audiences. Polishing their skills as storytellers in the BL genre, under the severe eyes of fujoshi, it was not long before people beyond the BL field began to notice them as creators of works of universal appeal.

Buy Issue 31