2023

London- What does it mean to be hardcore today in an increasingly overstimulated society? Numbed to shock value and vulgarness, how can we reassess the semiotics of sex to reveal the sexual truths of our time? ‘Hardcore,’ a group show on display at Sadie Coles HQ (Kingly Street), has taken a long hard look at the power dynamics of sex, its implications in intimacy, and our diverse reaction to it. It includes works from 18 artists, including Monica Bonvicini, Bruce LaBruce, and Cindy Sherman. In an accompanying essay entitled ‘Hardcore,’ written by Reba Maybury, also known as Mistress Rebecca, an artist, writer, and political dominatrix, Maybury writes:

“Discomfort links arms with curiosity. Pleasure holds hands with disgust.”

Curiosity and disgust are two central themes that dance in a devious dichotomy in Sadie Cole’s Knightly Street Gallery. When entering the upstairs space, you are met with curiosity at the sight of Monica Bonvicini’s Breathing (calm), 2023, an installation that imitates the appearance of a BDSM whip but scaled up considerably. It is suspended from the ceiling, producing a motor sound that punctuates the gallery space in an oddly calming manner. Perhaps it replicates the brief anticipatory moments before a masochistic administration of a whip, or it serves as a reminder of human scale and fragility.

“What does it mean to be hardcore today in an increasingly overstimulated society?”

Disgust is at the forefront of the space, most notably in two works by King Cobra, documented as Doreen Lynette Garner. In The Feast of the Hogs, 2022, is a silicone carcass suspended by a rope and chain laden with glass beads, crystals, and pearls. It is uncertain whether this carcass is that of a human or animal, but the uncanny mixture of flesh, bodily hair and textiles continues into a second work, White Bread, 2021. White Bread is more of a meatloaf, with the cross-section revealing bone and other internal detritus you would expect to find when cutting into a body. The flesh’s proximity to fur has semiotics similar to Meret Opennheim’s infamous teacup. Still, involuntarily you can’t help but recall the fictional prospect of vagina dentata or the all too real teratoma tumour, which have the same viscerally offensive combination of bone flesh and hair —google these at your own risk.

Curiosity and disgust are akin to Freud’s Eros and Thanatos, or life and death drive. Eros, the life drive in psychoanalysis, is linked to love and creativity, which Freud also correlates with our sexual instincts and libido. On the other hand, Thanatos is the death drive and is the self-destructive, sadistic and violent part of the ego. There is an unspoken assertion made in ‘Hardcore.‘ In the principle of pleasure, in its many multifaceted forms, “never identical” and “always unique,” it is in the coexistence of curiosity and disgust, and Eros and Thanatos, that pleasure is achieved. This is epitomised in works such as Bruce LaBruce’s Female Liberation Army, 2005, and Homosexuality is the Highest Form of Class Struggle (Slava and Brian Kissing), 2013. Though the images have an 8-year gap, they are visually highly similar. They both depict individuals of the same gender in a caress, an intimate intersection between intimacy and violence. Their naked bodies take the centre frame in blood-spattered rooms, each containing objects usually associated with war and destruction, such as an ak-47 or tin soldier hats. Perhaps the pinnacle of this principle is shown in Bob Flanagan and Sheree Rose’s Supermasochist, depicting Flanagan in a hospital gown strung around his shoulders like a fictitious protagonist with elaborate S&M devices attached to his phallus. Flanagan was submissive to Rose for a number of years until his eventual death at age 43 due to cystic fibrosis. The image is also the cover of a documentary entitled Sick, 1997,which details his life and eventual death. It discusses his conceptual, performance and video art that often pertained to pain, illness, sexuality, and its intersections.

It cannot be ignored that many of the works featured in ‘Hardcore’ are from the feminine perspective, which problematizes a reading of it via Freud without further integration. As psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster asserts: “Freud takes the unconscious as a woman.” “The opposition between the masculine precision of a bold formula, the one Freud sees clearly before him, and the murky unyielding veiled and resistant woman.”

It’s clear to Freud and many other masculine thinkers that the female body and mind is an unknown territory that presents more questions than answers. In cases such as the Greek etymology of hysteria, it equates a specifically female loss of sensibility to a ‘wandering womb.’ While disgust resides in the canon of fetichism, ‘Hardcore’ presents it as an inescapable experience in the conduct of pleasure. Whilst strictly male fantasy often places it as a niche interest, it seems that within the canon of the ‘female gaze’, it is a matter of fact. What is often mistaken in assessing such things for pornography or extreme vulgarity is, instead, lived truth.

‘Hardcore’ also has a notable recurrence of sartorial objects, including Elaine Cameron-Weir’s hairshirt with lucky cilice SS 23 cartoon violence collection, 2023 and Tayeba Begum Lipi’s Comfy Bikinis, 2013. In ways, it speaks to clothing’s presence as a fetish object. Clothing, aside from being objects of capital desire, also occupies a space in the realm of sexual commodification; as fashion theorist Valerie Steele asserts in Fetish, 1997, “The inanimate fetish object is often, but not necessarily, a piece of clothing.” Notably, the hairshirt and Bikinis in ‘Hardcore’ imbue elements of fetishised clothing and materials, such as the leather of the jacket and the form of the bikini, which, contrary to the name, doesn’t appear pleasant to adorn —depending on what you’re into. Fetish, 1997 presents a peculiar case of a safety pin fetishist who would become “glassy-eyed” at the sight or thought of the object, at times also being induced into actual seizures. Whether Lipi was aware of this acute desire is uncertain, but Comfy Bikinis appears to have a purposeful aversion to a bodily presence.

“While disgust resides in the canon of fetichism, ‘Hardcore’ presents it as an inescapable experience in the conduct of pleasure.”

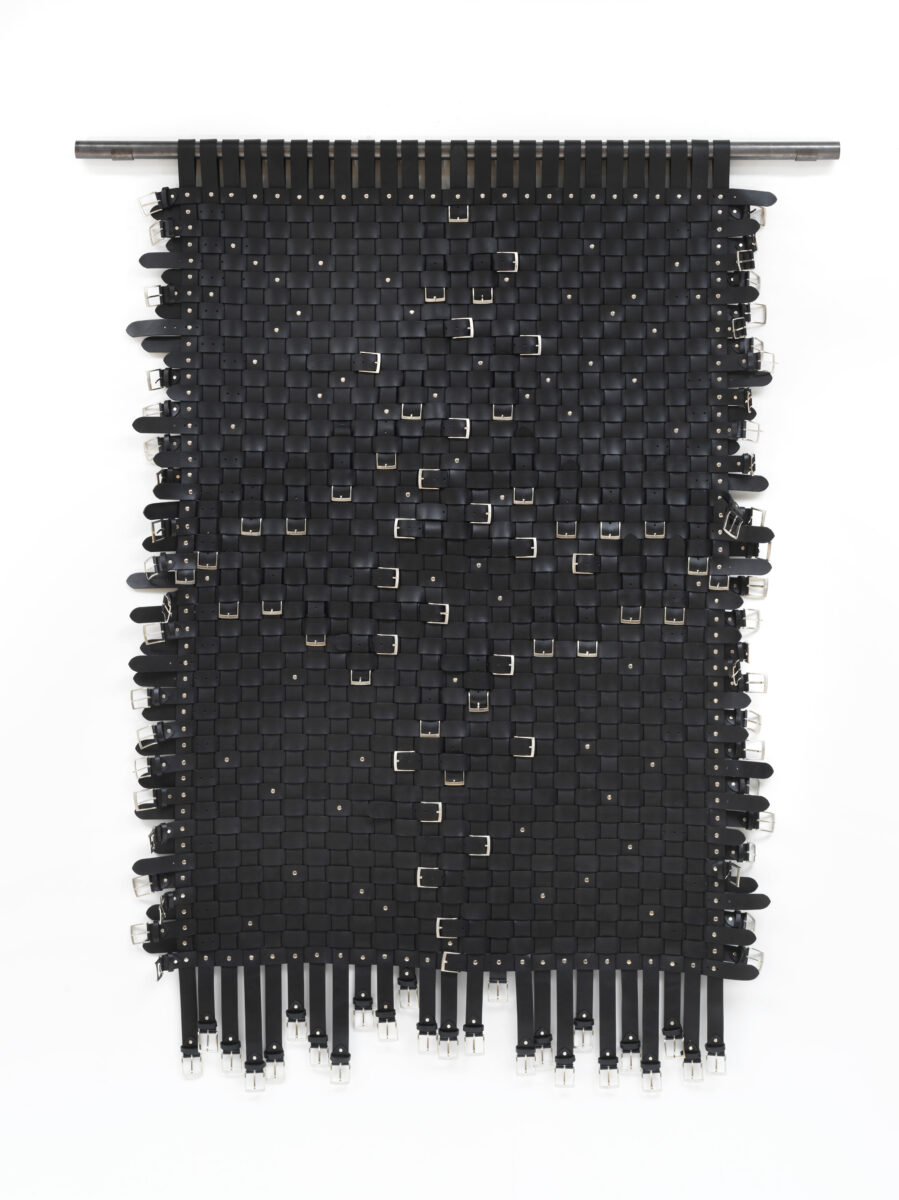

The flirtation of presenting a space where it appears a body should be but is not creates a peculiar but common scenario. The absence of a body makes space for fantasy, the imagined space it would occupy conjuring respective visions via the clothing’s innate connotations. Because of clothing’s inherent proximity to the body, it lives as a second to an individual experience, a storehouse of cultural and individualised memory. In this way, Monica Bovicini’s Beltdecke #6, 2023, plays on the existing connotations of a leather belt. Presented in a tapestry-like formant, Bovicini assembles many belts to create a wall hanging, whose buckles appear to make a faint outline of a cross in the middle. Aside from the connotations of the belt as a BDSM object, the way we engage with a belt, wrapping it around our bodies, tightening it or loosening it accordingly, changes our bodies and breathing consequently, which instils its own set of power dynamics, obedience, resistance, and restraint.

It’s clear that despite the inherent shock value that some of the works may produce, ‘Hardcore’ does not seek to redefine its name or viscerally offend you but confront you with the truth of what is already there. Curators Sadie Coles HQ and John O’Doherty epitomise its mentality in the statement: “The concept of ‘Hardcore’ is not to scandalise or titillate, but rather to represent without judgement.”

Words by Lucy Broome