It feels as though Bill Viola’s sprawling retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao begins before one even enters the building, surrounded as is by such vast amounts of water—a key element in the American artist’s oeuvre. Other elements of Viola’s works feature outside too, with Yves Klein’s Fire Fountain (1961) blasting five columns of flames upwards at night.

Inverted Birth (2014) is the first work I encounter inside the exhibition, which draws together pieces by Viola from the seventies to the present day. The video plays out alone in a blacked-out room, towering over spectators. At the moment I enter, an orc-like man is standing tall on screen, muscular and covered in a liquid substance so thick and black it might be mud. Initially it conceals him almost entirely. The liquid rises, licking around his body, accompanied by a powerful but muffled noise as though the viewer is listening to a waterfall through earplugs. As it climbs the liquid turns blood red, then white and eventually clear, leaving the figure clean and calm. The screen turns black for a moment before the process begins again. The deluge, though ferocious, at no point feels dangerous, the man standing solid, washed in reverse in the colours of birth.

“My trajectory has always been based on the influences I received from many sources,” Viola tells me in correspondence prior to the show’s opening; “from reading texts and poetry of the Sufi and Christian mystics; from the teachings of Zen Buddhism, where I learned about the universal questions of human existence; from other artists throughout the ages, including today’s media artists such as Nam June Paik and Peter Campus, from whom I learned technique and the endless possibilities of video. So, I feel that I have been exploring the same themes but in different ways.”

One of the works the artist has been most excited to see presented in the exhibition is Slowly Turning Narrative, one of the most technically daring creations, dating from 1992. “That year I made nine new installations,” he tells me, “more than I had ever done, and I was experimenting with the physicality of objects, adding sculptural elements to the works. This piece has a large rotating screen mounted in the centre of the room. On one side is a normal screen, on the other side is a mirror. A projection from one side of the room shows a jumble of images with loud sounds; a carnival, a carousel, kids playing with fireworks. On the other side of the room, a black-and-white projector shows an image of a man’s face, sometimes straining. The room explodes with distorted images as the mirrored surface is hit by the projections. The viewer is immersed in the work as not only are they covered with the images that the mirror is shooting out, but they are also reflected in the mirror. The one constant element is the audio, a man reciting a mantra that I wrote using every verb I could think of: ‘The one who sleeps’, ‘The one who walks’, etcetera.”

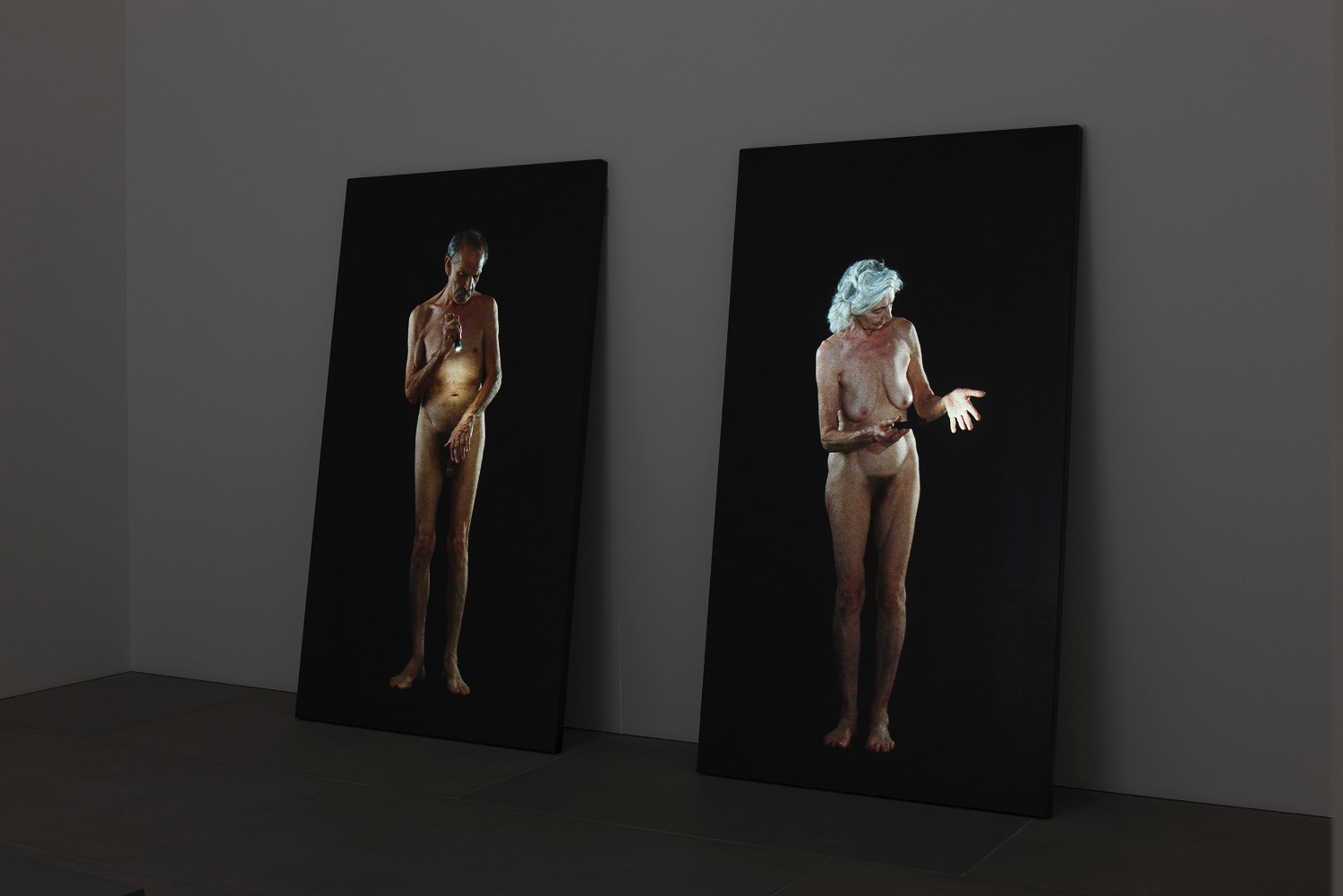

I wonder how the vast changes in film and video production have affected his practice over the years. “I use what I need to make each work,” he responds, “and I have never been hindered by the developments in technology, usually quite the opposite. Of course, video has become much more complicated than it was when I first started. Early on, in the late seventies and eighties, Kira (Perov, his wife and collaborator) and I were often just collecting images with a portable camera and recorder, travelling to the deserts, to other countries, other states, to find the images I was looking for: mirages, mountains, forests… Later, I needed to stage pieces that became installations. When the need came for using slow motion, we required a film crew and a team that could help with lights, sets and rigging. But I also continued to make simple works with just a camera and an assistant. Man Searching For Immortality/Woman Searching For Eternity (2013), a piece in the exhibition that depicts two naked older people projected onto two slabs of granite, was recorded with myself, Kira, the actors and one other person to help with camera and lights. On the other hand, Going Forth by Day (2002) was the biggest production we did; at times we had forty crew members with two hundred extras on the set.”

Earlier this year I visited Bill Viola: Electronic Renaissance in Florence where, once again, the city and show bled somewhat into one another. The exhibition focused on the influence of the Renaissance on Viola’s practice, placing his works side by side with the paintings that inspired them.

“I have always depicted an inner world that resides in our dreams or in our subconscious mind”

“Of all my works, both installations and videotapes, there really are only a few pieces that have directly been influenced by another work of art,” he explains. The Greeting (1995) is one of those. I was fascinated by Pontormo’s painting Visitation (c. 1529), not so much because of the subject matter, but the composition, the form and colour, and, most importantly, the emotion that the eyes are expressing. This is the humanism that figures prominently in the Renaissance.”

The Greeting is hypnotic: three women move to greet one another at hyper-slow speed, their garments blowing in the wind as though through water. Again, the sound is muffled, creating a sense of being cocooned. I’ve seen numerous Viola works before, but never at such scale, one after another. I have always seen the work as being dark above everything else, but on leaving the exhibition I felt calm and peaceful. “Perhaps the calming experience is the time necessary to see the show that forces you to slow down,” he says. “It is easy to spend two hours in one of our exhibitions. There is enough time to reflect on what you are seeing, and reflect on your own experience. Most of the works have a built-in positive aspect to them, with the cycle of birth and death there is always rebirth.”

The “our” used here is not royal: it includes his wife, Perov, who has been an abiding presence throughout the years. After inviting Viola to the university she worked at in the seventies, she moved from Australia to New York to assist him and has been at his side ever since. The couple now live in Los Angeles. Where one ends and the other begins can be a point of confusion (she also uses the term “our” multiple times when discussing the work, and the studio inform me that the written correspondence is aided, in part, by Perov), and yet she is somewhat of a silent partner—it’s Viola’s name stamped on each show.

“I think my title is Wonder Woman,” she jokes at the opening in Bilbao. What Wonder Woman means in practical terms is that she has gone from assistant to executive producer, in charge of decisions such as selecting performers, choosing costumes and “signing the cheques”. Perov is keen to emphasize “Bill’s ideas are Bill’s ideas”, nonetheless, she says she is often the one who can see which ideas need some time to develop and which are ready to move ahead.

“ I have never been hindered by the developments in technology, usually quite the opposite“

Each production is highly organized, everything carefully planned out in separate notebooks (one for ideas, one for the development of individual ideas once they’re ready and one for the practical side of things). Inspiration comes from many sources. “I usually start by reading something, or looking at art that has attracted my attention,” Viola says. “I take notes or write in my journal. Sometimes I will see a vision, an image that pops into my head, stimulated by my reading. At other times, I have an idea for a work based on a certain piece of equipment.”

Man Searching For Immortality/Woman Searching For Eternity reinterprets the nubile bodies in Lucas Cranach’s 1528 painting Adam and Eve, displaying the ageing male and female as no less inquisitive, right up to the end. “This piece is specifically about ageing and mortality, which will happen to all of us,” Viola says. “In other works, I often use a range of performers from different ages, ethnic backgrounds and genders, such as in The Dreamers (2013), to show our diversity.”

“A video camera has as much spirituality as a paintbrush,” Perov notes at the opening of the Guggenheim exhibition. There is such splendid sincerity in Viola’s work that it can feel at odds with the prevailing mood in contemporary art. The artist shows little desire to be ironic or to mock the lofty aspirations of previous generations. It may feel at first as though religion is the key inspiration but there is little solid notion of a god within the work, despite the influence of religious teachings and the history of art. The human is notably mortal in these pieces, but that doesn’t mean the philosophies of a less secular way of life don’t apply.

“All of my art represents my search for the spiritual that exists in everything,” Viola writes. “I have always depicted a world that is different to the one we all see as ‘reality’, an inner world that resides in our dreams or in our subconscious mind, a world where we can focus on the mysteries of life.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 32

BUY ISSUE 32