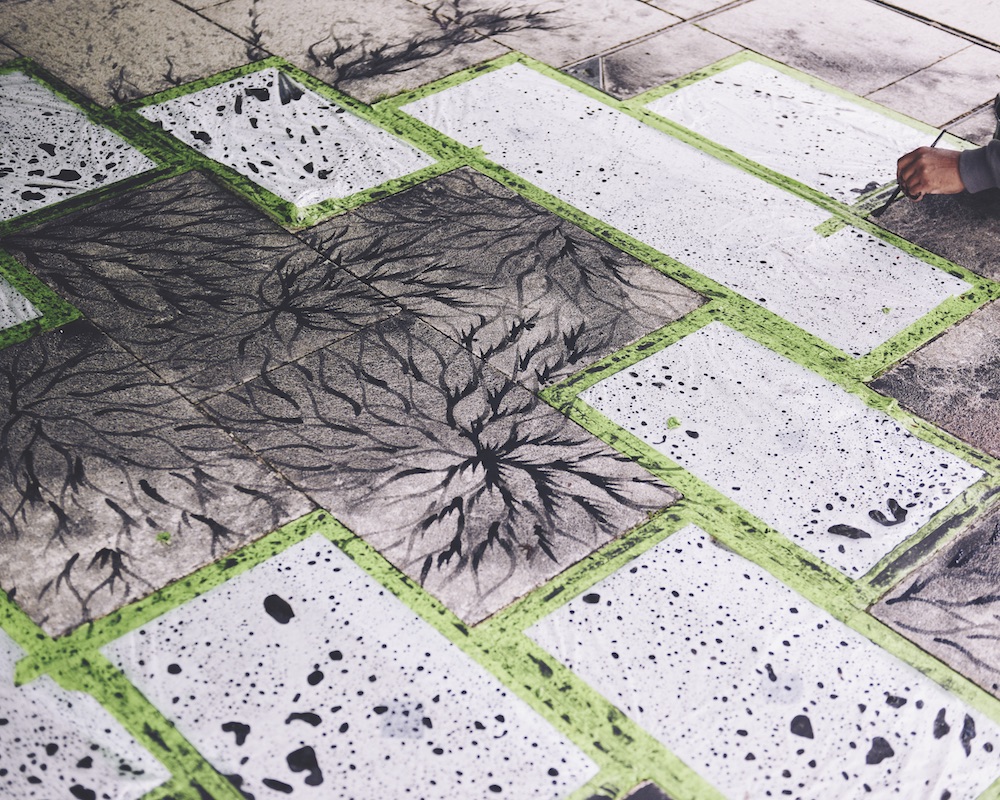

An unseasonably wet June may dampen anyone’s spirits, but for the Lahore-based artist Imran Qureshi the weather has proven to be the most challenging part of his latest commission. In Bradford’s picturesque Lister Park, a sunken pond garden has been subtly transformed: bags of soot appear to have been emptied onto the paved walkway separating the tranquil waters and smeared underfoot, while eruptions of red mingle with the grimy-black. If this suggests the aftermath of carnage, then it’s one where exotic blooms grow amid the charred remnants.

An unseasonably wet June may dampen anyone’s spirits, but for the Lahore-based artist Imran Qureshi the weather has proven to be the most challenging part of his latest commission. In Bradford’s picturesque Lister Park, a sunken pond garden has been subtly transformed: bags of soot appear to have been emptied onto the paved walkway separating the tranquil waters and smeared underfoot, while eruptions of red mingle with the grimy-black. If this suggests the aftermath of carnage, then it’s one where exotic blooms grow amid the charred remnants.

“It should be woven into the space naturally, so that you don’t feel that it’s something that’s been artificially placed”

But the piece, commissioned by 14–18 Now, the UK arts programme set up for the anniversary of the war and which was also responsible for Jeremy Deller’s “ghost soldiers” in a powerful enactment to commemorate the Battle of the Somme, is proving frustrating. “For this kind of work, you can’t cover the space with a canopy or any kind of stretchers,” Qureshi says. “It’s a very tricky thing. And I was so excited to be doing this work in the UK because the men who fought from this region, it’s not a very known history. But when the rain starts, you have to wait for hours sometimes. It’s very difficult. It’s becoming a very long process. There’s so much waiting.”

The other challenge for Qureshi, who really does look as if he could do with a good night’s sleep when we meet (he works solidly throughout daylight hours, weather permitting), was the scale of the piece. Although he has worked on large-scale commissions before, most notably on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s roof garden in 2013, he is best known for his miniatures, which follow the classical traditions of sixteenth-century Mughal painting.

“The real challenge was how big it should be,” he says of Garden within a Garden. “It can easily be lost in the space because it’s so busy. You have to think of the division of space, the levelling, the water, the other parts of the garden, the trees. You are thinking that the work should have a presence in the garden, but that it should also blend into the architecture. It should be woven into the space naturally, so that you don’t feel that it’s something that’s been artificially placed.”

That sense of balance is key to Qureshi’s work, as are the dualities he explores in terms of theme, namely those between violence and beauty, and death and renewal. His Barbican exhibition in the Curve Gallery earlier this year highlighted them to dramatic effect. Where the Shadows Are So Deep displayed his latest series of miniatures in a theatrically dim-lit space. The floor was covered in exuberant spillages of red paint which, with their bursts of blood-red flowers and bleeding tendrils, also coursed down the walls like a Cy Twombly painting. The miniatures glittered in the crepuscular gloom and featured uprooted trees and mounds of earth covered in splattered paint: exquisite gardens and depopulated landscapes struck by unseen forces, but in which the trees themselves appeared like wounded figures.

“Now other miniature artists can see so many other artists’ work and they can see the diversity in this tradition”

“I’ve always worked with these themes, whether directly or indirectly,” he says. “Whatever is happening politically or socially, or even if it’s happening emotionally, on a very personal level.” He acknowledges that the recent spate of Islamist terror attacks in Pakistan, such as the horrific 2014 mass shooting in a school in Peshawar by Taliban terrorists, have fed into the mood of his work, just as 9/11 influenced an earlier series of miniatures, which he called Mapping Terrains, which concerned geopolitical boundaries.

And yet, despite these thematic tensions, he never loses sight of the seductive beauty of the miniature tradition. Just like the Mughal court painters whose tradition he carries on, he uses gold leaf and a dazzling palette, in his case modern acrylic paints (which he also uses for his larger public works), rather than watercolours, which retain their colour intensity and richness. And although modern pigments are no longer made from natural plants and minerals, he prepares the paper and makes the brushes in the traditional way.

The cotton paper, called Wasli, is used specifically for painting miniatures, and Qureshi joins four sheets together with glue containing plain flour, carefully pasting them together to ensure that no bubbles remain. He makes the tiny brushes using bamboo sticks and squirrel hair. In traditional Persian miniatures, they use, he says, hair from a kitten’s tail. This ancient method involves tying the ultra-fine hairs together and inserting them through a straw which is actually the hollow shaft from a pigeon’s feather. Then the straw goes straight into a long bamboo stick, which is sharpened with a cutter to form a rounded tip.

Qureshi, forty-four, is noted for being the leading figure in the revival of miniature painting. In the early nineties, he attended the National College of Art in Lahore, which is the only college in Pakistan to teach miniature painting, having been introduced into the curriculum in 1982. Qureshi now teaches there himself, but as a student there were very few living artists who painted miniatures. “We never had many examples around us to refer to,” he says. “So we were struggling with ourselves, trying to find new ways of creating contemporary miniature painting. But now other miniature artists can see so many other artists’ work and they can see the diversity in this tradition. But at the time it was very challenging.”

Qureshi also talks of the struggle he had at the time in attempting to update and redefine the tradition. “A lot of people were completely against it. They were saying we were destroying the tradition—those people who were very traditionalist, which included even my own teacher, who was fantastic in terms of learning the classical skills and techniques, but he disagreed with the way I was crossing the boundaries of the miniature. There were certain rules, he’d say, such as saying that you can’t paint a miniature without figures in it.”

Much of his training involved copying old Mughal masters. “The training is very academic, very traditional and very disciplined,” he says. “And in the beginning it’s really hard. But then after that you’re free to do anything within that tradition, so it’s very exciting. And because your training is so rigorous, you feel like you have the ability of executing anything, any idea, to perfection.” Needless to say, this is a very different training to that received in most art schools, either in Pakistan or in the West.

“I really wanted the viewer to feel that characteristic of the medium—of how it feels alive, as if it’s almost breathing”

Still, despite this rather forbidding idea of perfection, Qureshi is happy to incorporate accidents in his work, and since there must be quite a few in so precise a medium that must be a good thing. “With every accident you learn something new,” he says. “Instead of getting frustrated or depressed I always try to take it as a blessing.” Indeed, he is not shy in suggesting that there is a deeply spiritual dimension to his work. When he paints he likens the experience to a form of meditation. It’s a feeling of deep focus and oneness with what he’s creating.

Since graduating, Qureshi has shown worldwide and is the recipient of the Deutsche Bank Award for Artist of the Year for 2013 and Pakistan’s ArtNow Lifetime Achievement Award, earlier this year. But it’s not just as a painter that he’s excelled. He’s also made sculptural installations using paper, and videos. One recent video work is called Breathing and shows a piece of gold leaf flying in space. “It was shot in slow motion,” Qureshi explains, “using a super slow-motion camera, which captures three seconds and stretches it into four minutes, so that the gold leaf is almost very still, but also appears as if it’s breathing.

“When I’m applying gold leaf in miniatures,” he continues, “it’s so alive before it’s pasted onto the paper, and when it’s pasted and burnished onto the paper I feel that it’s like killing the medium. So I really wanted the viewer to feel that characteristic of the medium—of how it feels alive, as if it’s almost breathing. It’s such a fragile material that when you’re using it you almost have to stop breathing yourself, otherwise it will be spoilt. And that aliveness, I feel, is the same with wet paint. When the paint dries you just don’t enjoy the living part of that medium.”

Photographs © Benjamin McMahon

This feature originally appeared in issue 28

BUY ISSUE 28