Was is it really only thirty years ago that Judith Butler first proposed that gender is a performance, that there is no physical sex-identity which precedes the social—that your gender is something you “do” not something you simply “receive”? That shift in thinking, so radical then, is becoming increasingly mainstream. Brian Dawn Chalkley—now seventy—is an artist who, even thirty years ago, was aware of his gender as a construction. He was a modernist painter in the then-conventional style, but in private he was a transvestite. That became public in 1996, and movement between his personae of “Brian” and the extravagantly bewigged “Dawn” has since become the wellspring of his art practice. Brian continues to teach at Chelsea College of Art—he loves it and never wants to stop. Dawn makes all the art.

Lots must have changed since you grew up in the 1950s?

Yes, the boundaries of male-female are being re-contexualized, and there’s a different imagination being applied by the younger generation. Thinking about that takes me back to my school in Stevenage. The whole aim seemed to be to train people to work in a factory, and I failed miserably in everything. I remember horrible moments of being confronted as different, and I see on reflection that even at eleven I didn’t have the male bonding expected.

You realized very young, then?

At ten. I remember trying on the lodger’s underwear, so that questioning of society has been there all my life. My parents were very liberal, though—at fourteen I painted a big question mark on the ceiling in my room. My father didn’t scream and shout “Get rid of that!” but said “That’s interesting, I wonder about that question mark”—and he left it there until he moved out himself, twenty years later.

Did you resist the construction imposed on you as a boy?

Exactly, yes. I couldn’t have articulated that then, when you’re like that you just don’t know what’s happening. Whereas now an adolescent can say “I want to be a woman.” That’s a problem too, I think, as it still implants a binary division between female and male, whereas I want to oppose that. The very word “masculinity” seems to define a clarity which I resist. I’m not denying masculinity, but embracing it in a much broader sense.

You became known as a painter, and led the MA at Chelsea College. When did you make your true nature public?

In 1996 I started to appear publicly as Dawn. It took a lot of guts at the time, but I was obsessive, going out every night to exhibition openings and performing as Dawn, too. There were mixed reactions. Some artists asked why I had to do that, but Paul Noble said “Great, send me some work!” and that led to me showing a film at City Racing in 1998.

Can you pin down the appeal?

Both personae are constructed, but the interest is in the point of transition between them. It’s that moment of “becoming other” which matters. You could say, if you’re looking at it conventionally, that most trans men look dreadful, but no one questions it in that world: it’s the change which matters, not its aesthetic. I’m quite conventional in my female representation, I don’t see myself as drag, or as theatrical in the way that Grayson Perry is—I used to see him often at parties in the nineties. As I wrote in my Manifesto of a Tranny in 2005, which looked to define such differences, “I am not for the respectable face of drag, as parody, as vaudeville, as family entertainment” but “I am for the badly applied make up. I am for the mirrored excess of beauty.”

Your partner is a woman. Whom did she meet?

She met Dawn in The Way Out Club. She loved Dawn, and said to me for a long time “I don’t want to see Brian,” so I had to dress up every time she came round until I said “We can’t carry on doing this.” I think she was attracted to the relinquishing of the male, rather than attracted to a woman as such. I come out of bisexuality—again, I see that as fluid.

How has being both Brain and Dawn influenced your art practice?

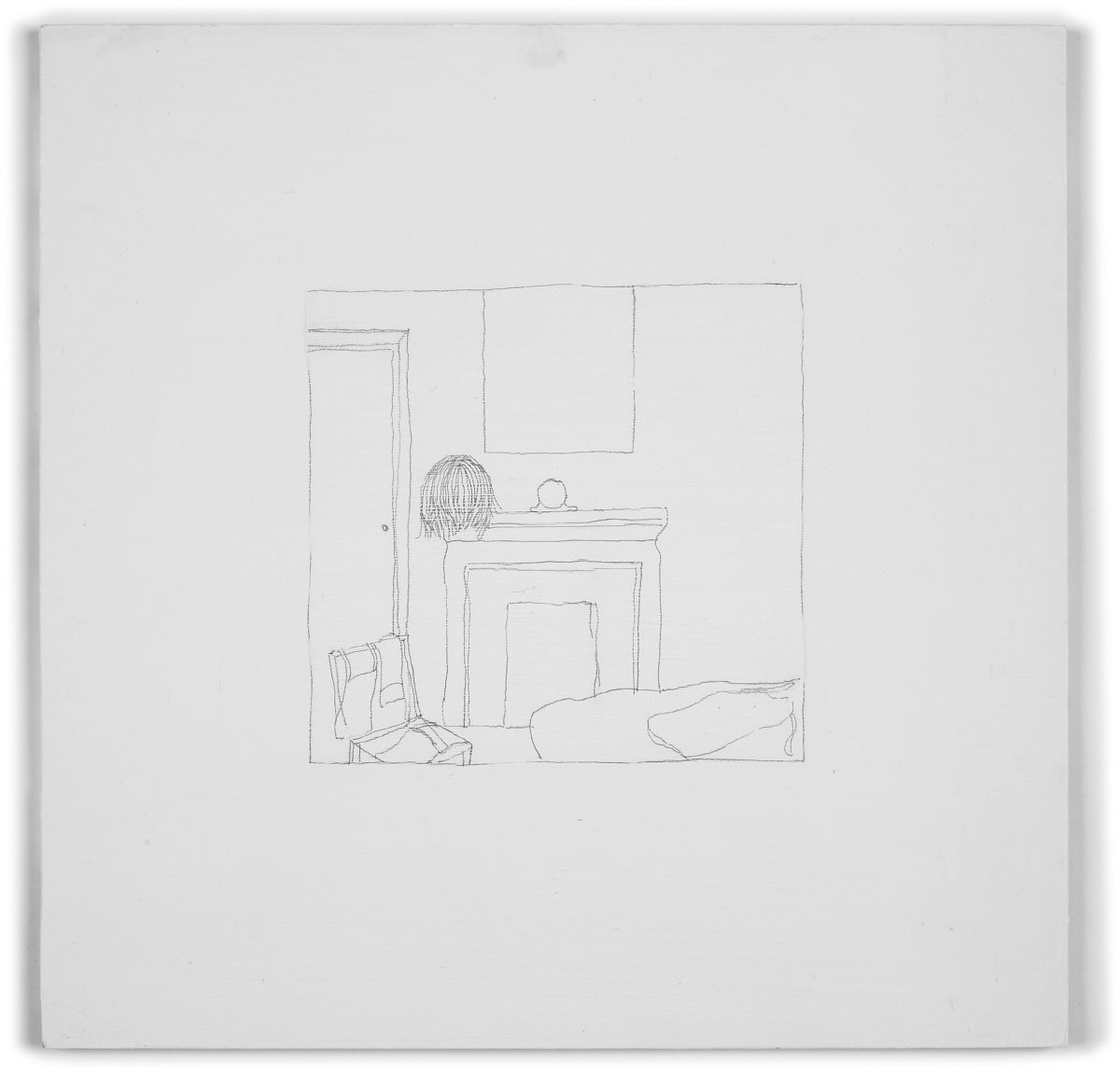

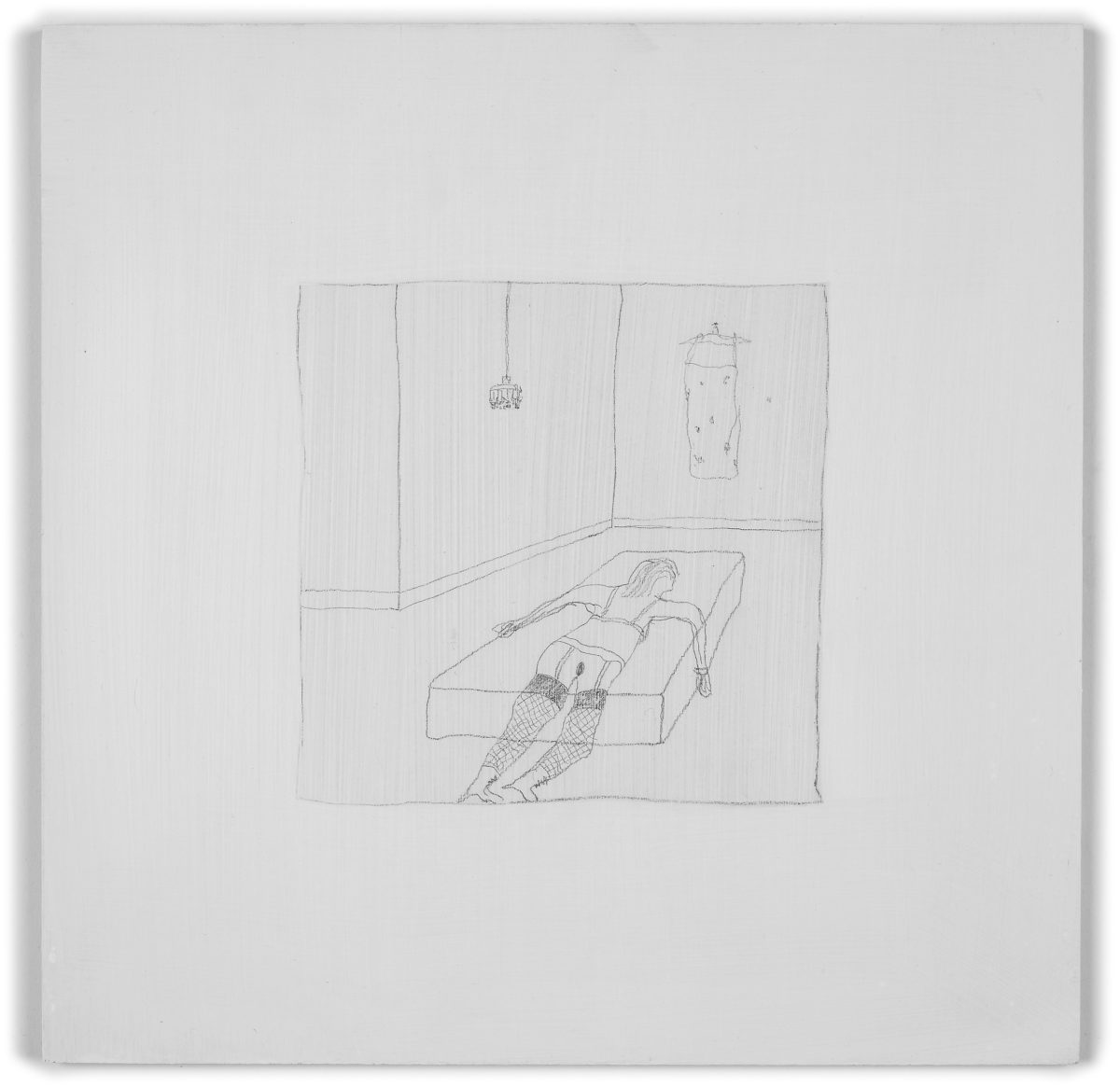

Dawn opened a broader landscape than I had as Brian, the macho eighties painter of big landscapes and steel abstractions. Being Dawn doesn’t carry the same art historical baggage. Her pictures started with line drawings on board—shown as Dawn in Wonderland in 2012-13: I noted them down at five in the morning, when I got back from the clubs. They’re very sexualized.

“The very word ‘masculinity’ seems to define a clarity which I resist. I’m not denying masculinity, but embracing it in a much broader sense”

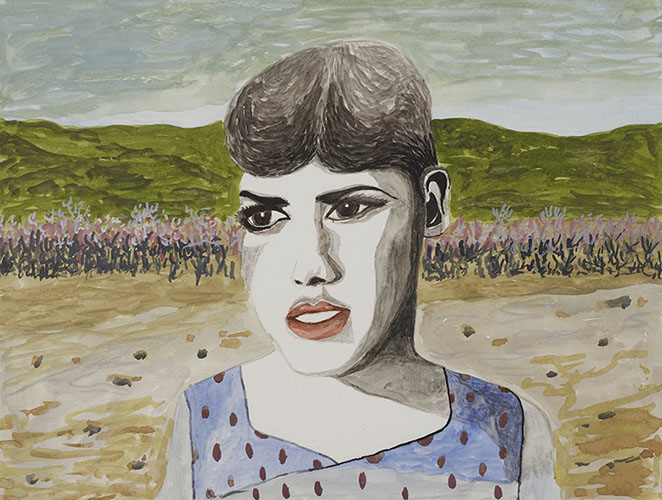

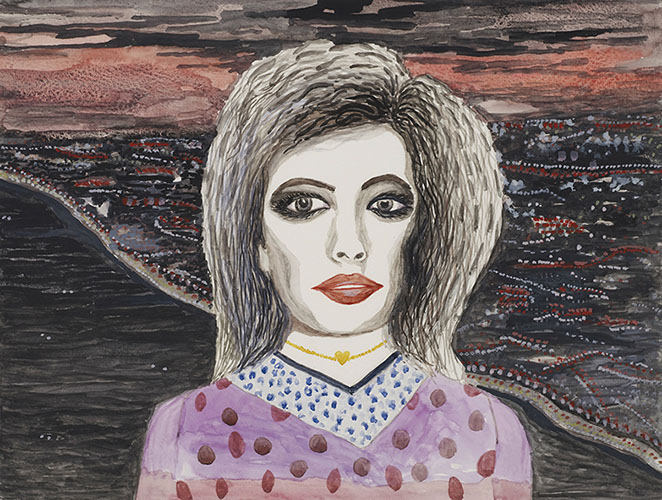

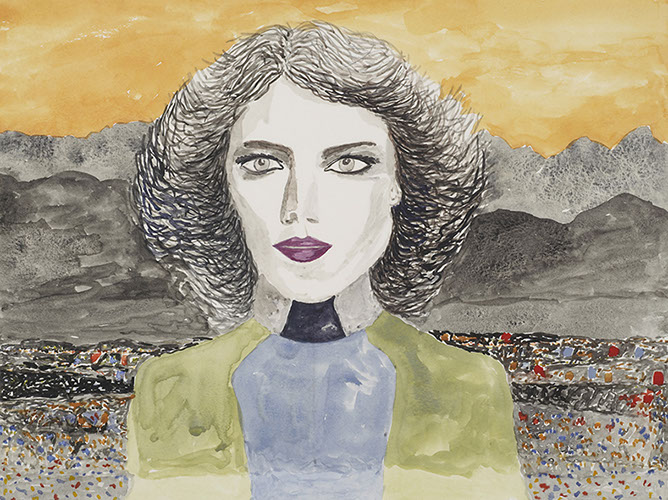

You introduced more complexity with the series Career Girls at Horst Schuler Gallery Dusseldorf in 2011. They have colour, narrative titles and elaborate backdrops and sneak the language of abstract painting into clothes and décor…

Yes, I started to paint figures of “becoming” Dawn, then I realized I wanted a background, so I invented settings to suit the figures as I imagined them, e.g. if I thought she was a croupier from LA then I would match that. Possibly I was trying out the characters I would like to be. Painting as Dawn allowed for a certain naivety in the painting… flat, and with lots of emphasis on the makeup. Putting on makeup is like painting a sculpture, and also performative.

- Watercolours from Missing exhibition, 2018. Courtesy Lungley Gallery

Your ongoing new series of watercolours, Lost, are much simpler—but there were already 454 when you showed them at the Lungley Gallery last year. How do you see these working?

Watercolours are a fluid medium in which to explore fluidity, and also suit how Dawn enables me to embrace the amateur. I like to bring figures and narrative together, and many of the watercolours incorporate fragments of text painting, integrated as imagined monologues rather than as titles. The words come in response to the image after I’ve painted it, drawing on a bank of texts I’ve jotted down from conversations or reading. The idea is to show them as an installation, as at the Lungley Gallery last year. The viewer jumps around between scores of characters and builds up a narrative view across the whole.