Every object carries a story. From holiday postcards to seaside trinkets, there are tales of migration, mythology and misapprehension. For Ingrid Pollard, the visual language of seemingly ordinary items has been the starting point for her decades-long exploration of the signs and semantics of representation.

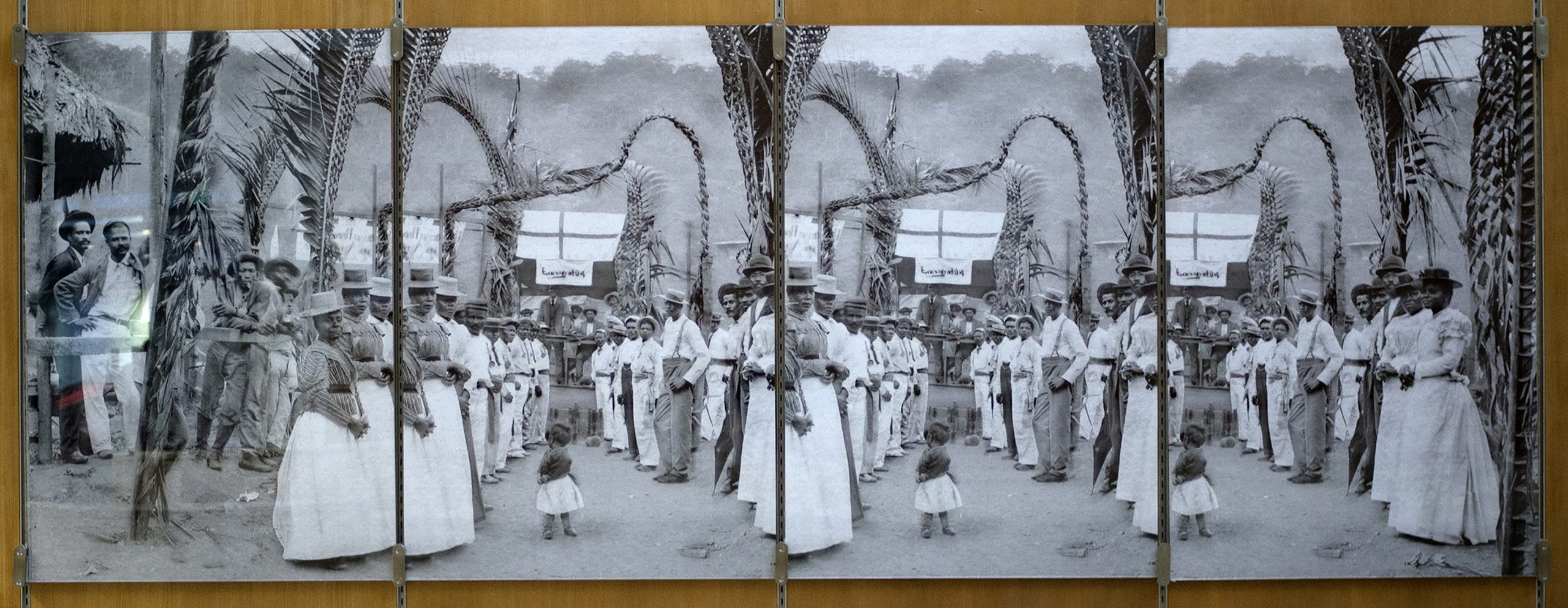

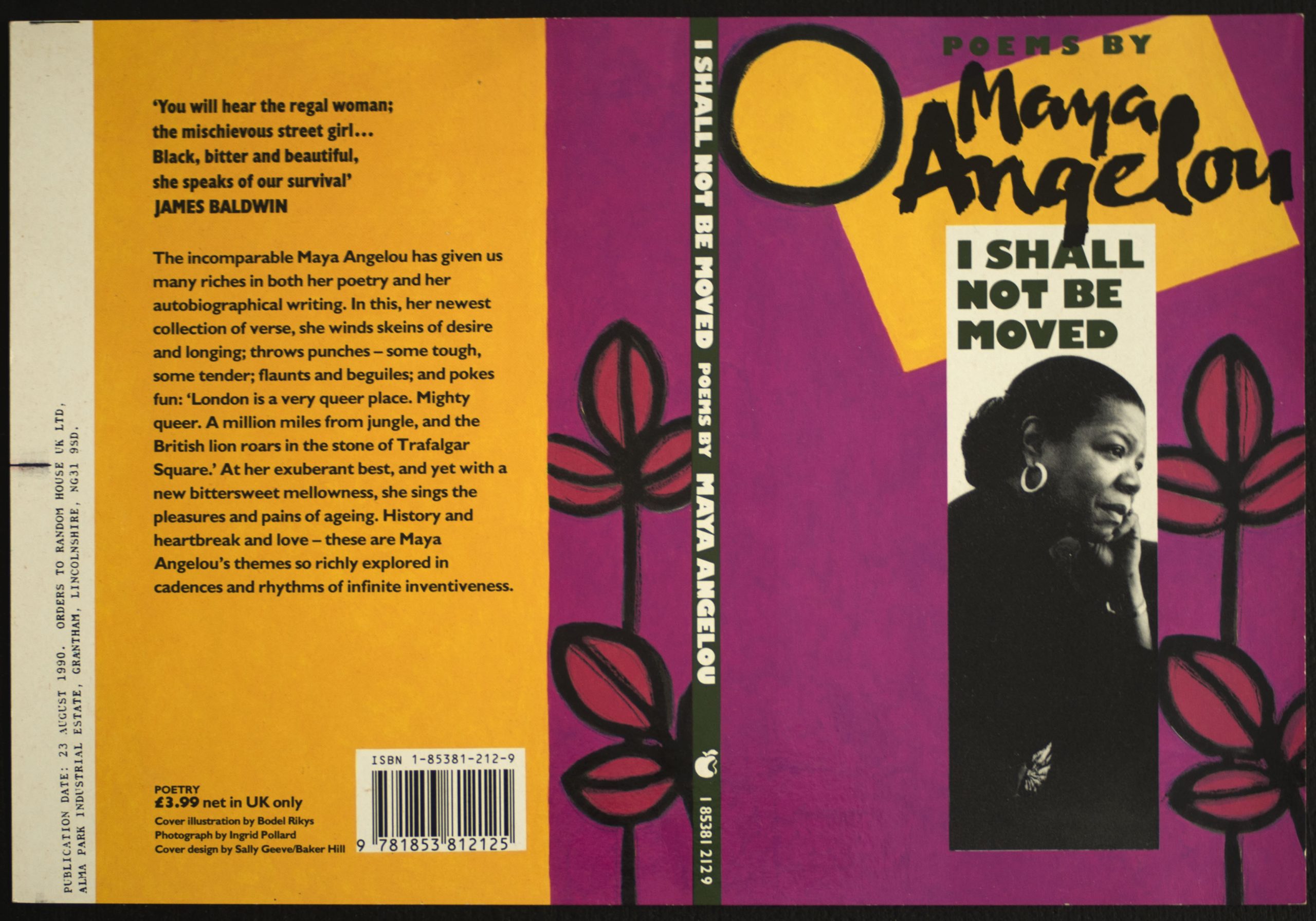

She tugs at these threads in her multidisciplinary work, which has seen her combine photography with printmaking, text, found objects, video and audio. “Because I work in photography, I have to interrogate my medium, its history and its developments,” she reflects when we first speak in early 2020. “It’s about the medium and its relationship to people.”

A cleaner; a gardener; a zoo worker… Pollard has been many things in her six decades. Born in Guyana, she moved to London at the age of four. Her father had worked as a printer at a newspaper in Trinidad, and owned amateur cameras, including a Box Brownie, and a 35mm camera which Pollard borrowed for school projects.

Pollard struggled with dyslexia and lacked the support she needed at school. “I wasn’t given proper employment advice, which may have been because I was a Black, working-class child,” she reflects, when we speak again in 2021. “I was just told to get a job in a shop. I knew I wanted to do something artistic, but I didn’t know how to apply for college. My parents didn’t know either. So I ended up in low-paid work, being a cleaner.” She bought her own second-hand camera when she left home and learned to use a borrowed enlarger to print in her kitchen at night. “I never thought of it as a job.”

“It’s not just about Black people and race. It’s also about beauty and technique and materiality”

Pollard has long been involved with community arts initiatives, initially at the Dalston Children’s Centre and the Lenthall Road Workshop in Hackney, East London. The latter was a printing space, started by three women in 1975, and offered darkroom and printing facilities to those who frequently found themselves marginalised in mainstream society, notably Black and working-class women.

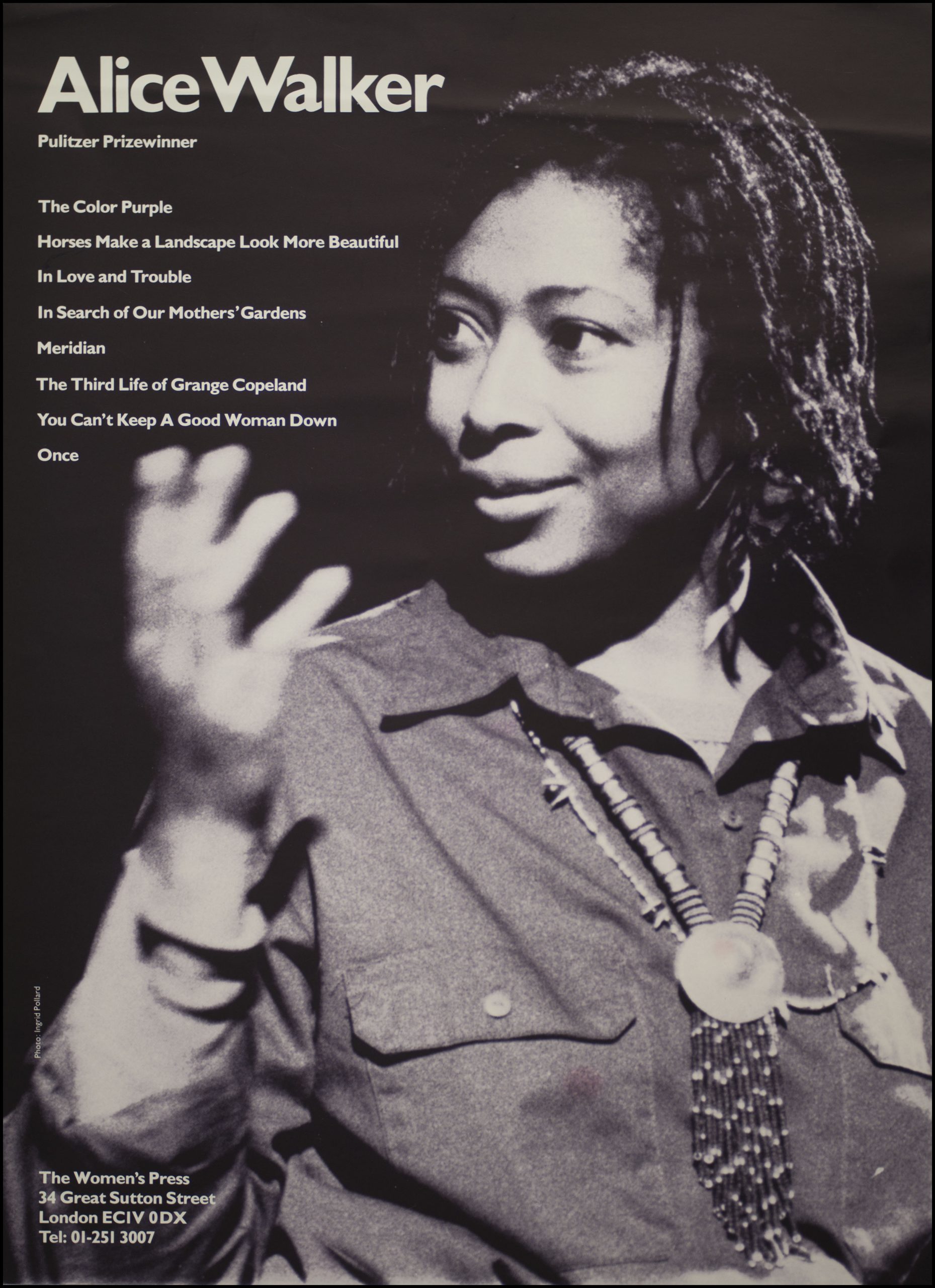

The Women’s Liberation newsletter was laid out and produced in a building next door, alongside now-iconic feminist magazine Spare Rib, which ran from 1972 to 1993. “I’d do photos and they’d end up in Spare Rib or Outwrite,” Pollard says. “It was an informal community of women working together. The difference between socialising, activism and hanging out was very loose.”

Pollard took her camera everywhere with her, her pictures offering a reflection of her daily life. “I’d go to see Alice Walker do a reading because I wanted to see Alice Walker,” she says. “It was much more spontaneous. And it wasn’t because we all wanted to be famous painters or famous photographers.” Her black-and-white photographs are intimately evocative, with particular attention paid to the quietly expressive nuances of gesture and motion.

Pollard revisited images from this period while in residence in the Lesbian Archive at Glasgow Women’s Library in 2019, where she focused on the activism around race and sexuality in 1980s London as a means of contextualising otherwise unnamed and uncategorised photographs. Pollard’s own archive documents life beyond the mainstream in London, in the period from the early 1980s onwards, and offers an alternate perspective on an era that has, at times, been dominated by the queer male gaze.

“People are crawling out of the cracks to want to speak to me, which is great. Why didn’t they speak to me 20 years ago?”

“The gay women from that era have been less presented, less shown, I think,” she says, mentioning artists such as Isaac Julien and Sunil Gupta. Pollard and Gupta later collaborated to help establish Autograph, the Association of Black Photographers, in 1988.

In recent years there has been a renewed focus on the lesbian artist communities of the 1970s and 1980s. However, Pollard is unsentimental about a community and era that many are quick to mythologise. “I think we were all ambitious. But politically, we were reluctant to sell to collectors. We wanted our stuff to be in institutions where they’d be well looked after and available to a wider public.”

She points out that Tate and the Victoria & Albert Museum have since acquired her work (“They realised that there was a huge gap in their collection”). It’s part of a recent flurry of recognition, including the University of Sussex’s inaugural Stuart Hall Research Fellow in 2018; the 2019 BALTIC Artist Award; and a solo exhibition at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes in 2022.

At a time when commitments to change have been made by high-profile galleries and museums in response to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Pollard finds herself at a unique juncture. “There’s a flush around race and the work of Black people,” she says. “People are crawling out of the cracks to want to speak to me, which is great. Why didn’t they speak to me 20 years ago? That’s the question that’s also got to be asked. But it’s nothing new.”

“Because I work in photography, I have to interrogate my medium. It’s about the medium and its relationship to people”

Does she believe that these promises will be kept by institutions? “I think some people will come through, but it’s a long game. Especially the young Black people that are being brought on now. You want to protect them and say, ‘It doesn’t matter if you think you’re famous now. What’s your ten-year plan?’” She pauses, sighing. “I don’t want to be negative, but you do have to be resilient more than anything else. You’ve got to be able to do this for 30, 40 years, and with delight.”

Pollard’s work often focuses on race, but it is about far more. “It’s not just about Black people and race and all the things that traditionally they’ve said that this work is about,” she says. “It’s also about beauty and technique and materiality.”

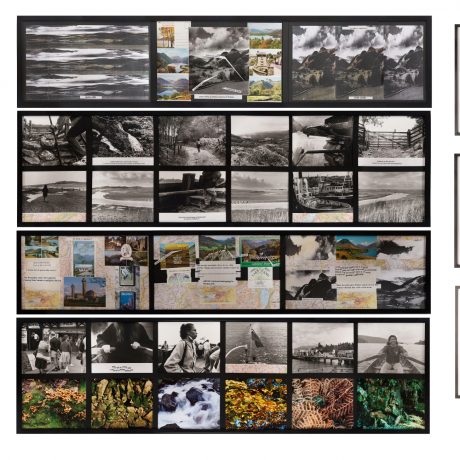

Over 40 years Pollard has interrogated the power and physicality of the photograph itself. In Contenders (1995), she cut up aspirational ‘before and after’ images of bodybuilding from boxing magazines, combined with real paraphernalia from training sessions, to unpick the male body as it prepares to fight.

“It was an informal community of women working together. The difference between socialising, activism and hanging out was very loose”

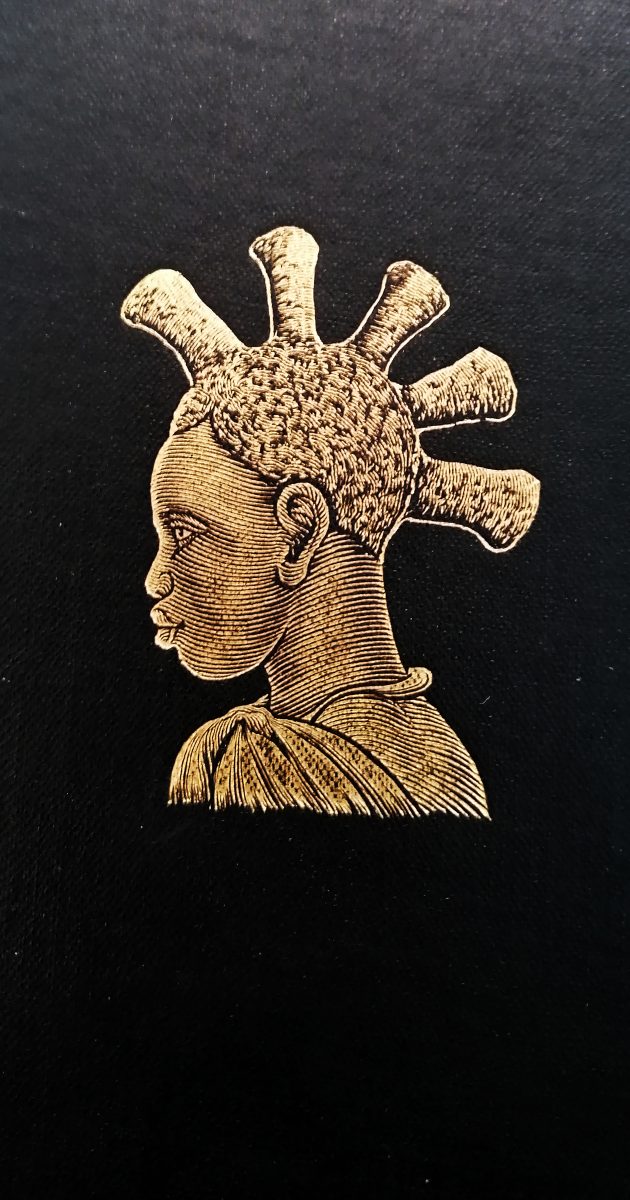

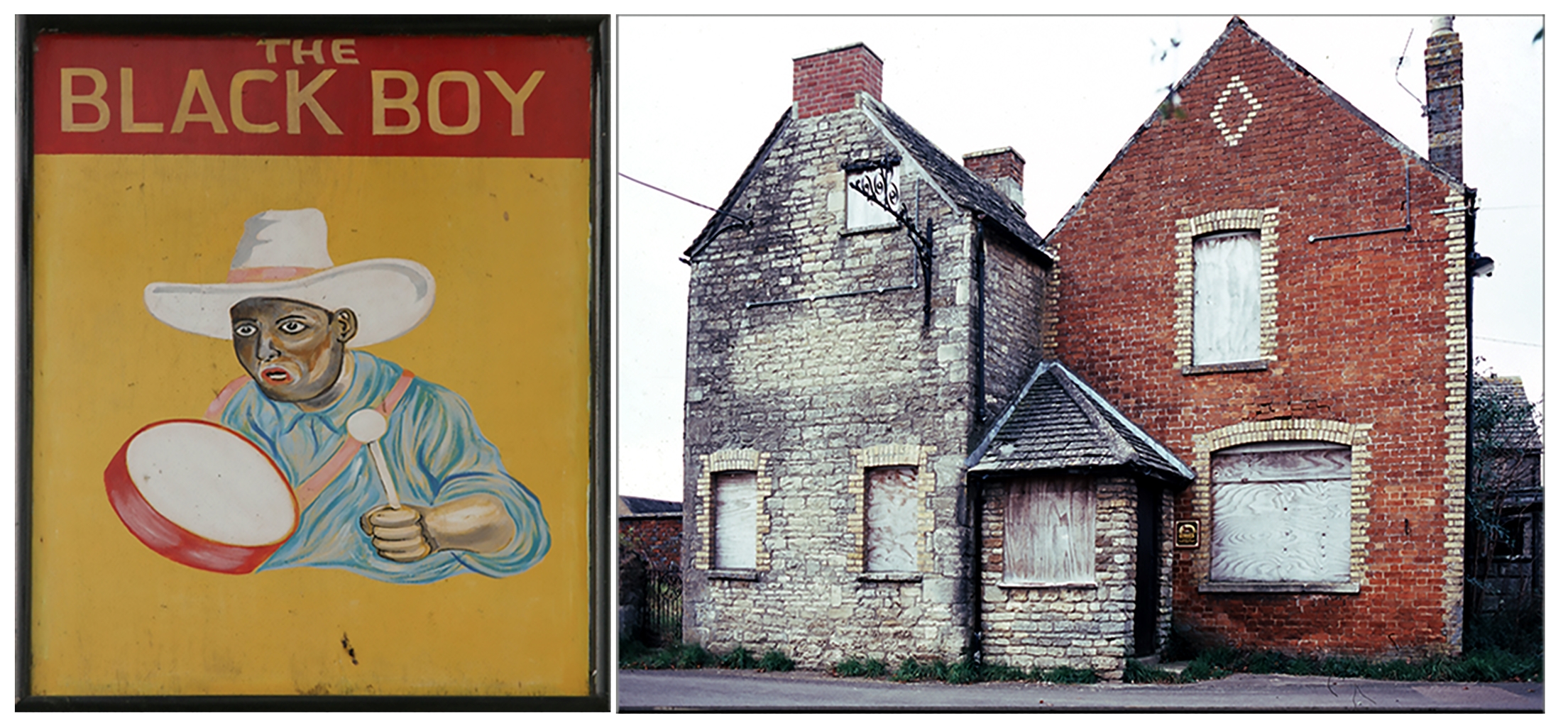

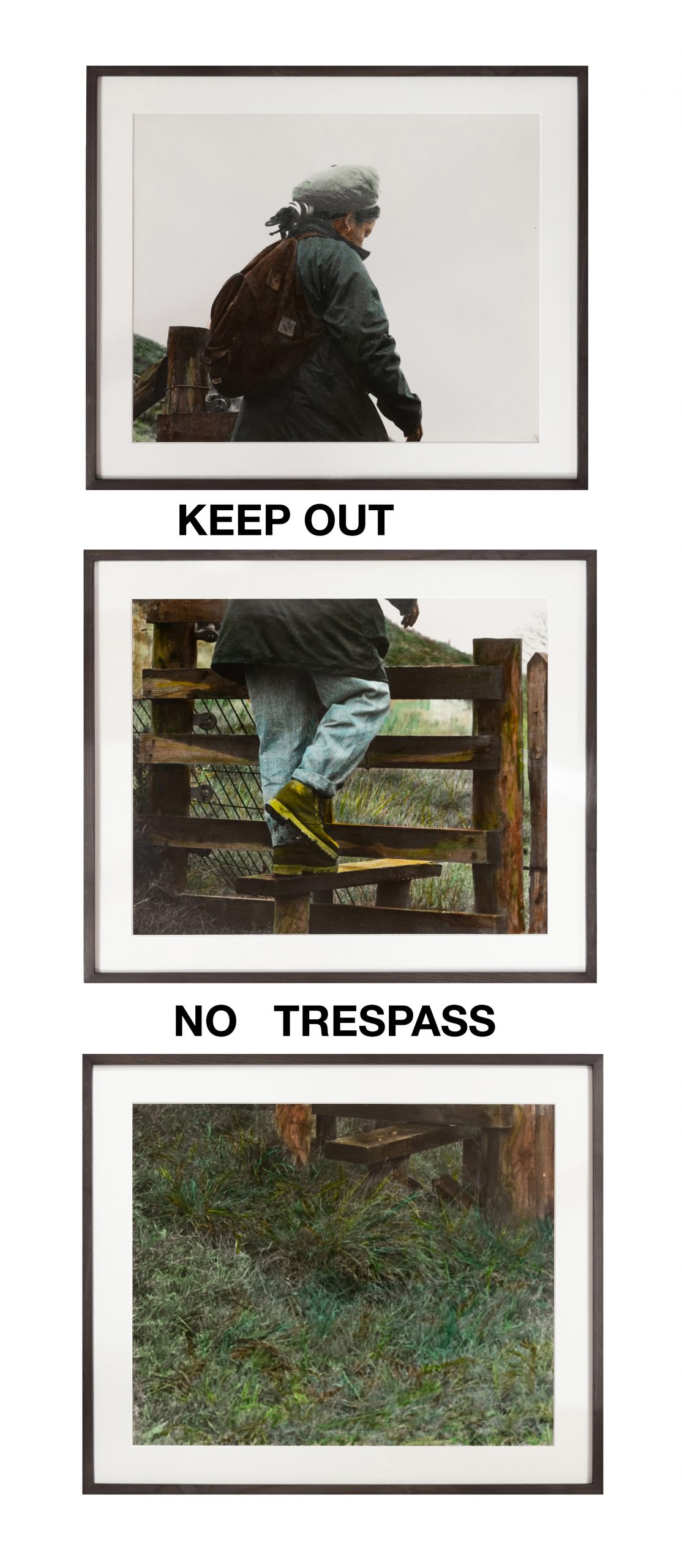

At BALTIC in 2019, she presented Seventeen of Sixty Eight, an exploration of the representation of the Black figure in British life, as seen in the 68 pubs across the UK that have ‘Black Boy’ in their name. The exhibition brought together photographs, sculptures, video, found objects and historical artefacts, and told a story of racism and an unsettling colonial legacy that remains in plain sight. “I never want people to just walk in and think, ‘Oh that was nice.’” she says. “People have got to work in my exhibitions and spend time thinking, ‘Why is that there?’”

It is reflective of Pollard’s manner: self-possessed, firm and direct. She has long operated outside the spotlight, connecting directly with local communities, an approach she has no plans to abandon as her profile grows. “You don’t stop doing the other stuff,” she says. “You look for alternative spaces, or you do slightly different things.”

Pollard’s practice is rooted in lifting others up, in facilitating change and becoming immersed in the lives and stories of real people. As she continues to push the realm and definition of photography, she draws on four decades of experience to build an unwavering, alternative vision that goes far beyond the establishment.

All work images courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Elephant 45

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor