I was five-years-old when Uncle Hamad taught me how to draw. We were sitting on grandma’s sofa when he leaned over and gently whispered, “Shall we draw your mum?” I remember being sucked into a web of enchantment as he explained proportion, composition and the importance of detail, making sure I included each contour of mum’s shoelaces. When finished the resemblance was uncanny and everyone appeared impressed, even my discerning grandma. Little did I know, at the time, Uncle Hamad’s health was rapidly deteriorating from HIV/Aids and this memory of him would be my last.

Hamad Butt was born in Lahore in 1962 before moving to London at two-years-old. In his youth everyone remembers his polymathic tendencies, his brothers and sisters ferrying crates of books to and from the library every day to quench his insatiable thirst for knowledge. He would also mural his bedroom, colouring the walls into life.

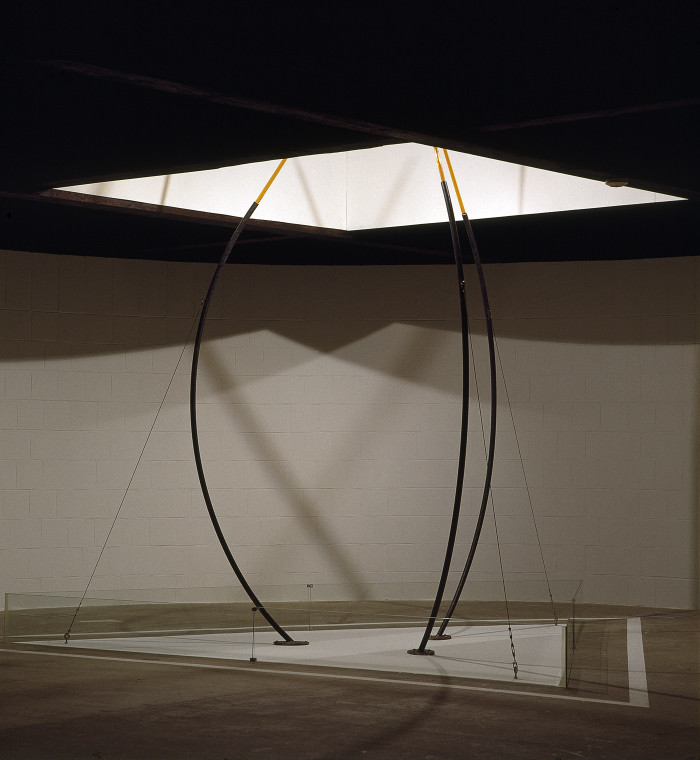

Transmission, 1990. Installation at Milch Gallery, 1990

But this artistic passion was discouraged as his brother, Jamal Butt, explained in a recent discussion about his work: “If I was to be fair, growing up in an Asian family in the seventies and eighties, art wasn’t a preferred profession if I put it delicately—it was either medicine, law or accountancy and it was the same in our family—art wasn’t a thing that you pursued. I think times have changed now, but he struggled with that—he struggled to find a place to express himself.”

“Typical of my uncle was his ambition to integrate chemistry within a dialogue of spirituality and religion”

After a short stint training as a biochemist and briefly attending Central Saint Martins, he enrolled at Goldsmiths University to study fine art and it was here that his final year project,Transmission (1990), went down in Goldsmiths’ history as the highest grades ever awarded to a final year student.

The installation featured a wall-mounted glass vitrine, which contained paper soaked in sugar solution, encrypted with elliptical sentences and impregnated with fly pupae. Over the course of the exhibition the flies hatched and lived off the sugar paper until they died, symbolising “an endless cycle of information, literally eaten and digestibly passed on”. Supporting this, on the floor, were nine books made from sheets of glass, accompanied by an ultraviolet light beam and safety googles, as etched onto the open page was a triffid, in reference to John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids.

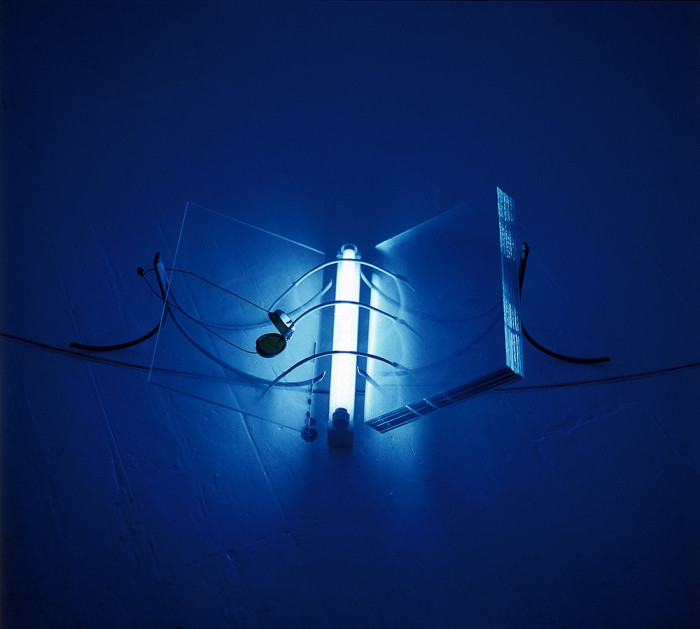

- Familiars Part 2. Hypostasis, 1992

Of the piece, the artist said in a rare home video: “It’s called Transmission because it’s transmission of light as a metaphor and the obvious because I was using ultraviolet light. Ultraviolet light is an invisible light available in all light, and is kind of invisible knowledge available in all knowledge but the closer you get to it the more dangerous it becomes that’s why the shape of books is in a circle, which you then have to cross over to get the safety goggles to actually read the book.”

Typical of my uncle was his ambition to integrate chemistry within a dialogue of spirituality and religion. His Muslim faith is hardly ever mentioned when talking about his work, but as a gay man he found Islam both challenging and enlightening—dedicated to an inclusive religion that simultaneously forbids homosexuality.

Continuing with Transmission, which was also exhibited at Milch Gallery in 1990, he said: “There was certainly a relationship to religion, which was the holiness of the books, and the holiness of knowledge, in a way there was a kind of play with the whole notion of blind faith in written things from other places, which I was equating with disease transmission through the use of flies. In fact the book when opened looks like a large moth or fly.”

The late eighties and early nineties was the height of the HIV/Aids epidemic around the world and transmission of the virus was at the forefront of his mind; my uncle witnessed many friends dying while also struggling to overcome the illness himself. It is what, I believe, makes his work even more poignant. “Hazardists” was the term used to describe artists within this particular art movement of the twentieth century, with fellow Goldsmiths alumni Damien Hirst cited as the “pioneer of art as a health hazard”. Little do people know Transmission came before any of the “hazardist” work Turner Prize-nominated Hirst has come to be known for.

Transmission caught the eye of the former director of the John Hansard Gallery, Professor Stephen Foster, who commissioned his first solo exhibition, Familiars—now in Tate’s permanent collection. Professor Foster said: “Hamad was such a genius—I’ve used the word in public many times—I do believe he was the closest thing to a genius of any artist I’ve ever met and unfortunately he died soon after making this commission for us in 1992. It’s a remarkable piece of work and who knows what he would have done subsequently.”

“Erring constantly on the side of danger, each piece represents the tumultuous relationship we have with the devil on our shoulder”

Familiars (1992) comprises of three structures encasing lethal chemicals in fragile glass receptacles; Newton’s Cradle (Cradle) containing chlorine, a Venus Flytrap (Hypostasis) with bromine and a Jacob’s Ladder (Substance Sublimation Unit) encasing iodine that when heated, transforms from a solid to a gas. Erring constantly on the side of danger, each piece represents the tumultuous relationship we have with the devil on our shoulder, lulling us into a false sense of security.

Talking about Familiars, he said: “There is a direct relation to spirits contained in sculptures, usually of the devil. There was a period where there was a shift from medieval alchemical witchcraft to the modern rationalistic chemistry—a shift between purity of the self and search for truth through purity of the self in alchemy to purely substance and physical quantity outside the self and the spirit has somewhat disappeared and it’s this dangerous spirit that I like and I think should be revived.”

After his passing in 1994, Goldsmiths University set up an award in his name in 1996, and his book Familiars was published posthumously the same year. As a child I remember attending exhibitions of his work, including Rites of Passage at Tate in 1995 and at Millais Gallery in 1998, when the entire family piled into a minibus to reach Southampton. I recall being in awe of the giant Newton’s Cradle, observing the chlorine-filled glass balls precariously hanging from the ceiling. Years later I see his art from a new perspective, as work that pushes us to think beyond preconceived boundaries, as an artist daring to challenge the limitations of science and as a man who asks us to contemplate our own mortality while he, courageously, succumbed to his ephemerality.