Diasporic artists tend to have a tricky relationship with home. Particularly for second or third generation immigrants, the notion of the word can be tenuous—is it possible to have multiple homes? Can you claim to be part of a nation which you’ve never inhabited? Even the word diaspora, with its multiplicity of pronunciations, seems to signal fluidity.

In particular, those who live in the UK or the US find themselves at the centre of a Eurocentric art world that has historically undervalued or outright shunned work from the countries of their heritage. In recent years, a hunger for diverse representation has engulfed the industry, and while many of those in power (curators, directors, critics) steadfastly hold on to their historic advantage, a space has increasingly opened up for artists of colour, a large proportion of whom identify as diasporic.

This space, however, does not come without conditions. The power to platform these artists still lies in the hands of a white majority, meaning that the work must appeal to a white gaze. This gaze can often tokenise, or even exoticise, diasporic work, which is often myopic to the nuances of migration and its effect on identity. Zarina Muhammad of The White Pube has described diasporic art as not so much to do with the identity of its maker, but more to do with “how these artists handle their identity as an object to deploy within the work.” To delve further than this, whose identity, exactly, is being deployed? What, or how much, claim can the diaspora put to the culture of its homeland?

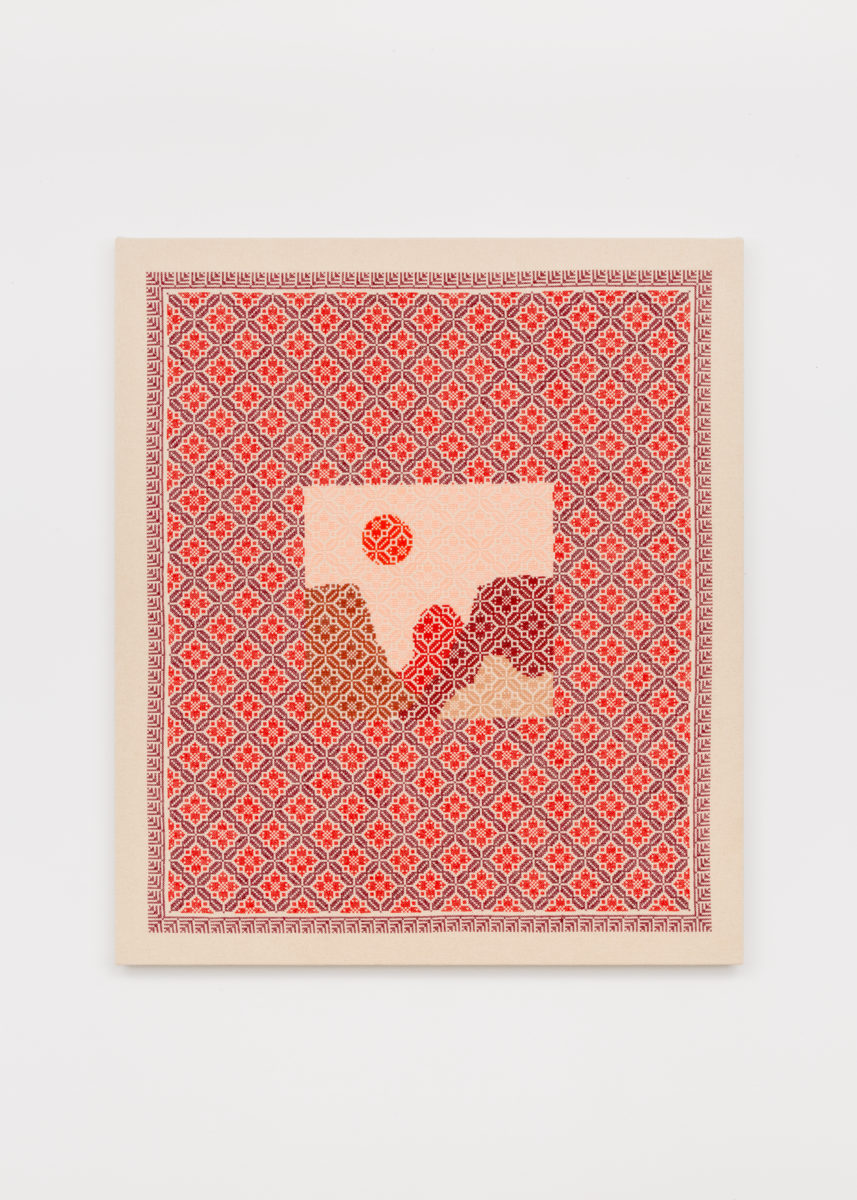

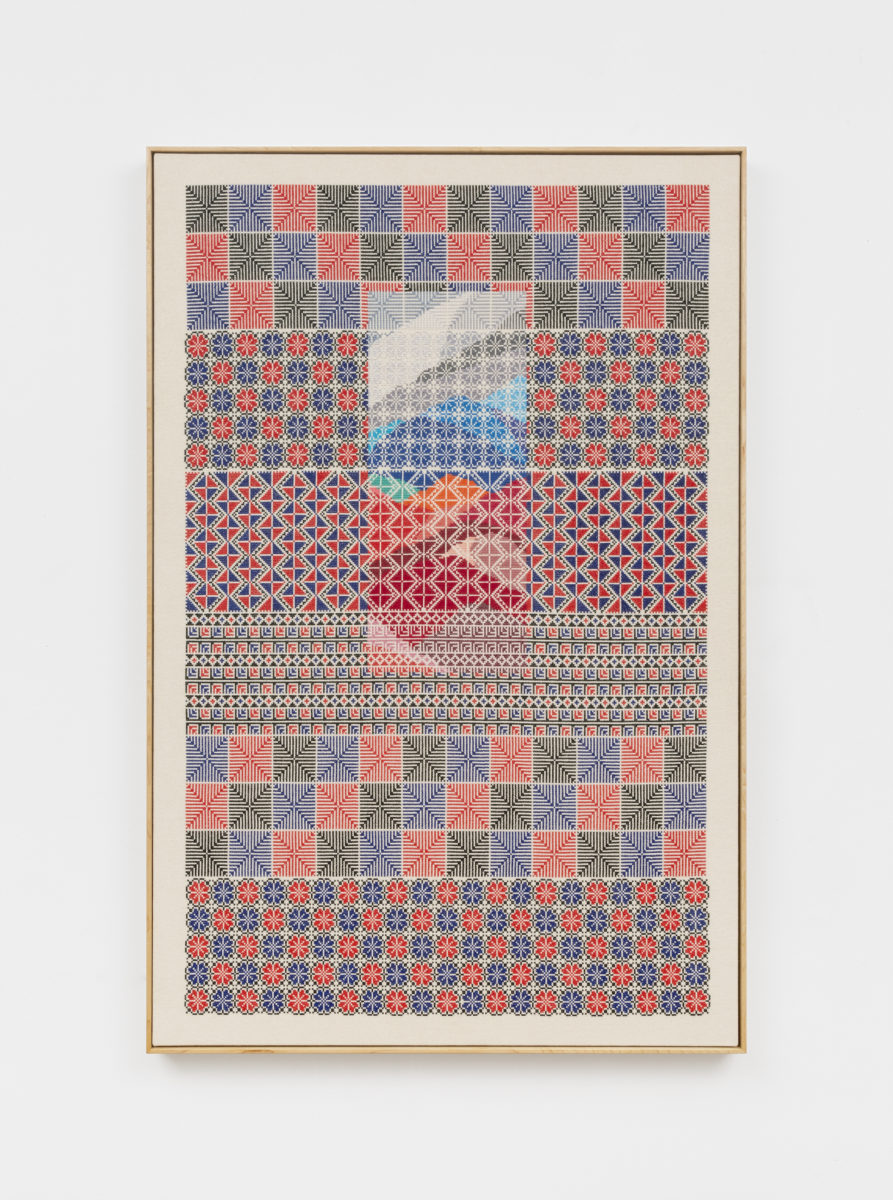

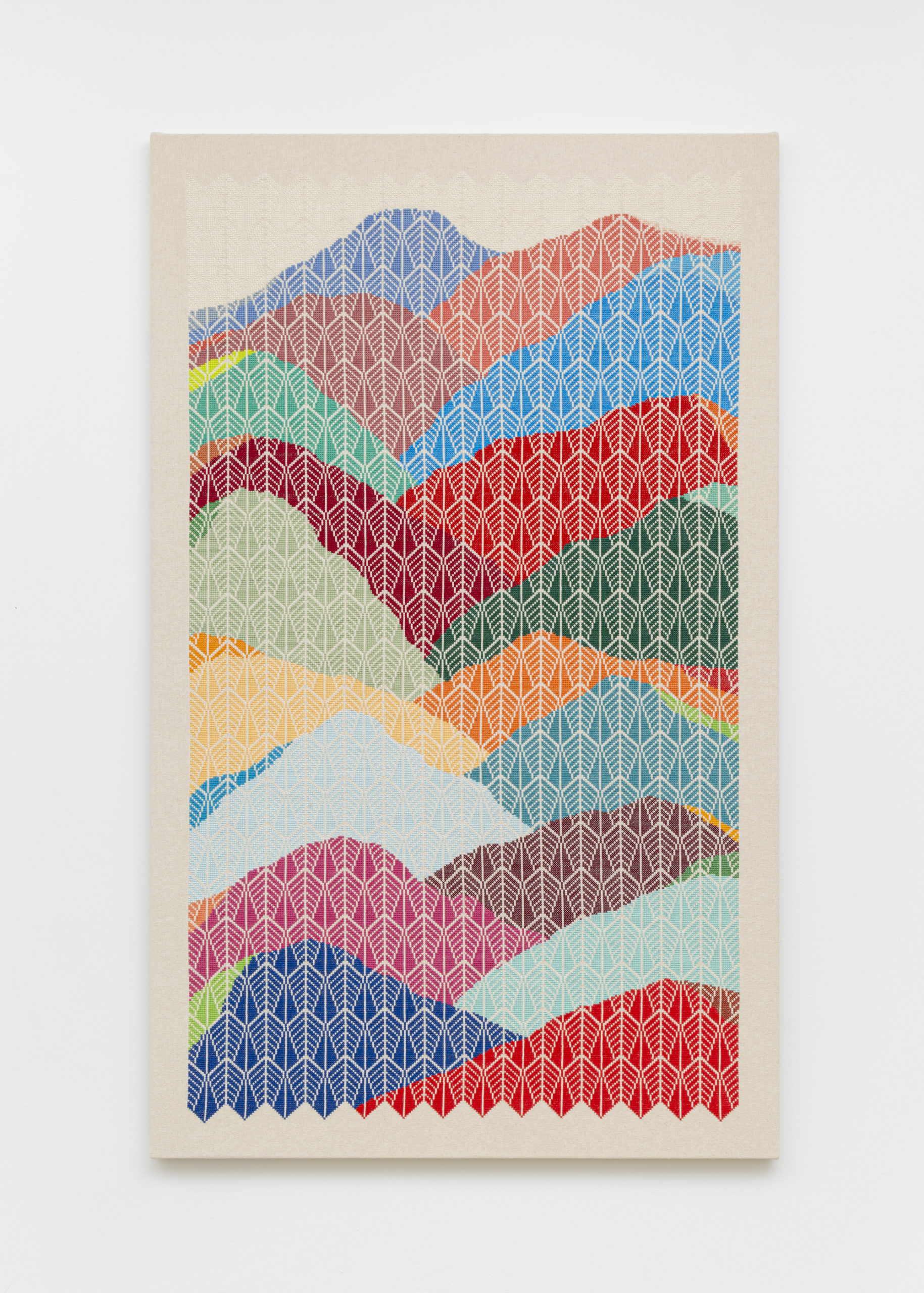

- Jordan Nassar, Left: A Lost Key Right: Gate of the Pillar. 2019

Inherited nostalgia

Jordan Nassar, a Palestinian American artist, states that in making work about his diasporic experience, specifically from a second generation American perspective, there is a distinction to be made. “I don’t attempt or claim to speak for Palestinians anywhere else, especially in Palestine.” Instead, he aims to share the feelings of “alienation, not-fitting-in, yearning for the homeland, and ‘inherited nostalgia’” that are cornerstones of his personal diaspora experience.

Nassar ruminates on this notion that diasporic peoples are “surrounded by material tokens of that fuller culture that we are missing, and so our understanding of that culture becomes in itself limited to these commodities—basically crafts and food and music, easily exportable things… that become all we have or know of our culture, thus rendering our understanding incomplete.” This results in an innate yearning for the homeland, inextricably fused with a feeling of foreignness upon arrival.

“The white gaze can often tokenise, or even exoticise, diasporic work, which is often myopic to the nuances of migration and its effect on identity”

Nassar’s practice is rooted in the craft of tatreez, a traditional Palestinian form of embroidery that the artist encountered as he was growing up on New York’s Upper West Side, with a Polish mother and Palestinian father. While tatreez is traditionally a woman’s craft, he began to practise the embroidery as a way to connect with his Palestinian heritage and roots “in a more meaningful way”. After practising this for a few years, he began to experiment with pictorial elements amongst traditional motifs, and uploaded an image of an embroidered mountain to Instagram. The Los Angeles-based gallery Anat Egbi contacted him immediately, resulting in Nassar’s first solo show in 2017, and the following year he debuted his collaborative tatreez works at Frieze New York. His career has risen exponentially ever since.

“About four years ago, this work brought me to an artist residency program in Jaffa, and while there I met Palestinian embroiderers, and since have also been making collaborative works with them,” he explains. These embroiderers, all women, are part of the communities of Nassar’s friends and family in Palestine. He describes the process of working in tandem with them. “I lay out traditional Palestinian embroidery patterns in a composition, then I remove sections of it which I intend to embroider myself later, then pass the design to the women to embroider their part first.” They choose how the colours are situated on the page, capturing what Nassar calls the “living cultural practice” of embroidery tradition. Upon receiving the work back, Nassar completes the empty sections, responding to the aesthetic choices the women have made, embroidering in his “diasporic” fashion, to meet the indigenous style halfway.

Education and social change

This collaborative exchange is echoed in the work of The Typecraft Initiative, founded by Ishan Khosla, Andreu Balius and Sol Matas. Launched in 2012, the initiative develops typefaces based on the “rich crafts and tribal arts of India” in partnership with local craftswomen, and aims to provide opportunities for craftspeople to “earn through the creation and sale of the typefaces and allied products.”

The idea originated in Khosla’s MA thesis at School of Visual Arts in New York in 2005. Upon returning to India, he set up his own design studio in 2008; The Typecraft Initiative was born in 2012. Khosla states that he wanted to engage with India’s rich folk arts, get out of his comfort zone in the city and travel to rural India. But he also wanted to start a discourse on what Indian design can include, “beyond the Modernist tropes designers are taught in the country or the cliché of Bollywood and truck art being viewed (in the West) as an epitome of Indian graphic aesthetics.” His thesis discussed the need for communication design to address broader social aspects, such as literacy, that transcend the interests of corporate clients.

Khosla liaises with craftspeople through collaboration with local NGOs, like Rangsutra, a company that is owned by over two thousand artisans across rural India. This third party ensures that the craftspeople, who are often women, are comfortable during the workshop, setting the “tone, pace and manner of working”, according to Khosla. It is essentially a skills trade—the craftspeople learn about typeface design, while the designers learn about indigenous craft.

Although Khosla only dabbled in a diasporic experience through his studies in New York, he is thoroughly aware of the urban privilege he holds. India is a vast country that houses a huge variety of cultural differences, and navigating different communities must be done with care. He explains that “in some communities, such as with the Sodha Rajputs, men are not allowed to enter the workspace where married women are working.” Because of this, it’s mandatory that Typecraft Initiative workshops are led by women.

“Although Khosla only dabbled in a diasporic experience through his studies in New York, he is thoroughly aware of the urban privilege he holds”

Although the initiative’s initial intention was to bring about social change, Khosla admits that since the workshops are only conducted over a few weeks, it’s not always possible to measure this—however, at times, they can instigate shifts in mindset. “One of the villagers said, in confidence, that the emphasis of letters in the workshop made the women realise the importance of education…. In fact, by the end of the workshop, a few craftswomen such as Paami told us that they wanted to learn English.” Khosla also recalls noticing that the daughter of one of the craftswomen in Barmer had resumed school after a few days of the workshop, whereas she had been helping with housework beforehand.

- Left: Nirmala, one of the Barmer appliqué craftswomen designing the letter B, based on paper-cuts and motifs created earlier in the workshop. Right: Charu lata ben and Amisha ben at the Soof workshop, where they are initially getting to make their own letterform designs using the basic geometric building blocks of soof embroidery

Non-native immersion

Born and raised in China, artist Jessie Yingying Gong set out to study and live in Europe in 2011. This journey prompted within her a “fascination with the topics of memory, identity, symbols and language.” One of her projects, Nüshu Works, explores a script developed and only passed on among the female population of small villages in the South Hunan Province. Gong discovered the script during a period of research, and was enamoured with its “rhombus form, reminiscent of dancing figures.” The culture goes beyond a writing system—Gong explains that it includes “singing, poetry, embroidery, calligraphy and sworn sisterhood.”

Before travelling to the area, she had no relationship to the craft and artisan practices, but as someone who practices calligraphy herself, became intrigued with the “diverse aspects of craft that come together in the application of Nüshu”. The writing system is an act of defiance—Gong elaborates that women who practiced it gave themselves a voice in a restricted and patriarchal environment by inventing their own secretive way of writing. After the standardisation of Mandarin Chinese and the Cultural revolution, it became a dying practice. “Nüshu now stands at an interesting historic point—where it is witnessing a revival of interest and considered a cultural heritage, [while] being utilised for touristic and monetary purposes in a governmental and social structure that remains patriarchal.”

She recalls asking herself as a person “not native to the land and the practice… what is my own position in relation to Nüshu?” Gong presents the work as a research-based project “providing an extensive and honest background to the subject (images, writings, audio recordings). I spent time in the Nüshu villages where I immersed myself in the daily lives of these female practitioners.”

Khosla is vehement in crediting the craftspeople he works with. Alongside mentioning them in any promotion surrounding the project, they also profit from sales of the typefaces they have a hand in creating. When I asked Gong how she credits the artisans, she said that she planned to return to the villages with a more extensive research video project in mind, but the events of 2020 scuppered these plans. She’s in touch with some of the women on social media, and credits them when images or recordings are presented. “Although I have not yet been able to provide the local women remuneration for their time and expertise, I intend to bring awareness of this unique writing system and practice through more accessible and shared resources.”

“How can we begin to examine our mixed-up dual cultural inheritance in a way that doesn’t capitalise on the experiences of others?”

Gong goes on to describe how she contributed to a female coder group on developing a free open-source Unicode font and provided necessary connections to linguists, scholars, designers and artists in relation to Nüshu. Nassar has a different response, explaining that the women he works with “have asked to remain anonymous… it would be wrong to expose them against their wishes.” He liaises with them through a production manager, who is part of their community, and Nassar’s friend. “They do commissions all the time, whether it be for the local community or foreign clients. So I am, in essence, just another customer.”

The fluidity of dual heritage

It is integral to use art to widen understandings of different cultural forms. Members of the diasporic community often inherit only certain elements of a culture, arguably experiencing them at surface level (as Nassar refers to). In order to engage in a more authentic way, it makes sense that one would collaborate with people who have dedicated their lives to craft—note that almost all of the craftspeople that these artists liaise with are women. It’s easy, at a first glance, to see these relationships as paternalistic—local people provide cultural fodder for others to gain exposure and profit from the Western art world (Gong has exhibited at the Venice Biennale, Nassar’s work is on display at the Whitney). I wonder however, if this reading takes into account the nuance of these projects.

As a second generation Indian immigrant myself, these issues weigh on my mind. How, then, can we begin to examine our mixed-up dual cultural inheritance in a way that doesn’t capitalise on the experiences of others, when the system that we exist within prioritises our white-adjacent, global and thus more palatable voices?

To return to the idea of the word “diaspora” itself being attached to fluidity, I wonder whether we can extend this ideology into a critique of diasporic art. Perhaps it makes sense to embrace somewhere in between the categories of Problematic or Not, within an inconclusive space of working things out. This might look like slowly but surely unpicking the strategies that whiteness has taught us: the practice of plucking from cultures at a whim; bestowing glory on an individual rather than crediting a group; exoticising otherness. This can only happen by reaching out, making mistakes and trying again.