Staying up late has always been a statement of intent. It sends us into a twilight zone that represents liberation, creativity, decadence and determination: the will to cut loose, and also to get things done. At this point in the twenty-first century, numerous global galleries and museums have devoted major shows to nightlife culture, including Night Fever at Weil am Rhein’s Vitra Design Museum, or the recent Sweet Harmony at London’s Saatchi Gallery. Into the Night takes this trending topic to the Barbican; it also offers an alluring departure from contemporary studies: focusing on the burgeoning cabaret and club cultures between the 1880s and 1960s in varied cities across the world, including Europe (Vienna, Berlin, Paris, London, Rome), Africa (Ibadan), Asia (Tehran) and the Americas (New York, Mexico City).

Into the Night might also be viewed as a creative contrast to the Barbican’s previous acclaimed Modern Couples exhibition; where that group show explored “art, intimacy and the avant garde”, this collection takes us from private realms into social spaces, with all the febrile expressions and dynamics they yield. I headed Into the Night with friend and former colleague Dave Swindells (Time Out magazine’s influential previous nightlife editor, whose photography featured prominently in both the Vitra and Saatchi exhibitions). For the many generations of us who’ve grown up clubbing, there’s something intriguing about a glimpse into pre-DJ nightlife; in my own hot-headed youth, I might even have considered this era alien, prehistoric, rudimentary… I’m older and (mostly) wiser now, and Into the Night explodes all of these clubby preconceptions, in gloriously vivid colour.

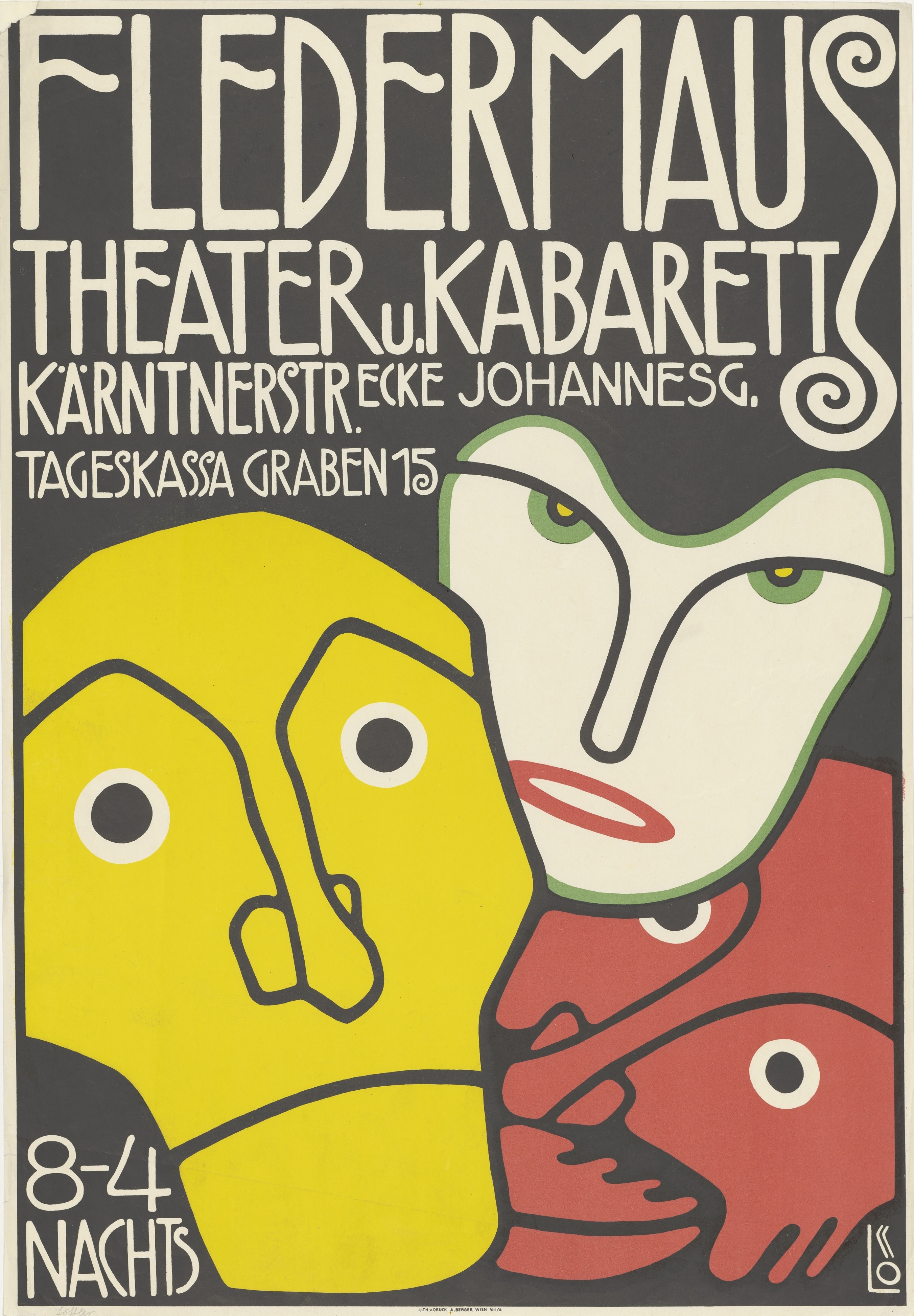

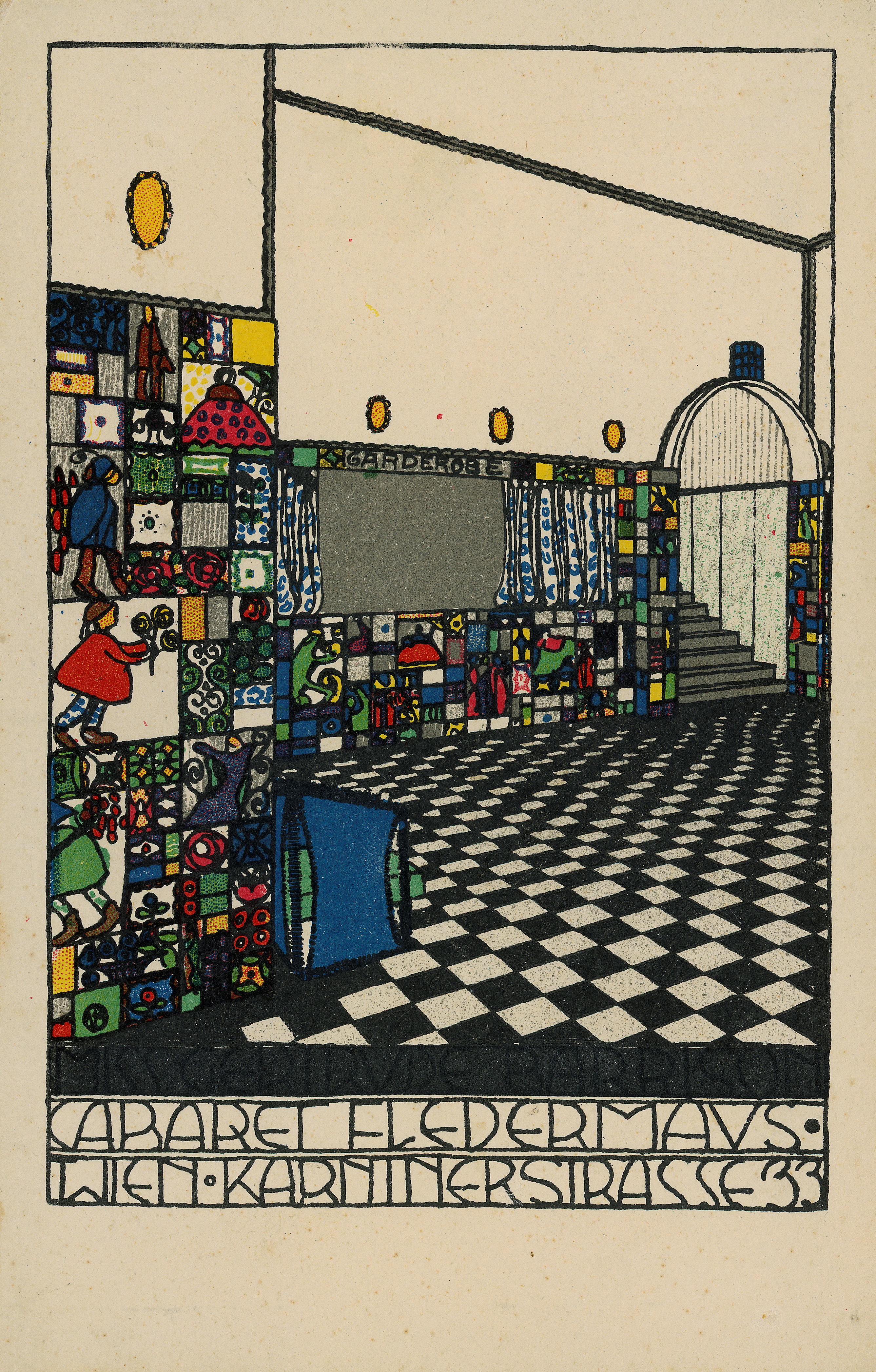

Vienna’s Cabaret Fledermaus was a fantastically stylish early twentieth-century hotspot for creatures of the night (“Fledermaus” translates as “bat”): a venue for experimental performance and exotica, and like all the clubs highlighted here, a meeting-spot for artists, writers and revellers. Viennese proto-modernist Peter Altenberg summed up the venue’s spirit (“The Fledermaus is young and full of propulsive energy”). There are nods to Johann Strauss II (Die Fledermaus) and Gustav Klimt, and the designs displayed are thrillingly bold, whether it’s richly hued poster artwork by Bertold Loffler or a pre-Metropolis Fritz Lang, or Josef Hoffmann’s immaculate interior design (including a 1907 metal plant pot and ashtray). Hedonism inevitably brings to mind destructive acts, and while many contemporary clubs boast cutting-edge design, it makes you wonder if they’re built to last in quite the same way.

“Nightlife is presented here as a reaction to the atrocity of wartime, a multi-purpose place for debate in times of conflict, and surely a universal human need”

Into the Night is rooted in historic moments, but it also feels impressively timeless; many of the nightspots featured here actually blazed briefly yet brilliantly, such as subterranean Soho joint The Cave of the Golden Calf (1912–14 in London’s Heddon Street—a backstreet now also notable for the telephone booth featured on David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust album artwork, and fancy Moroccan restaurant/club Momo), or Zurich’s groundbreaking Cabaret Voltaire (1916): a drinking and dancing den, and arguably Dadaist birthplace (experimental poet Hugo Ball announced the Dada manifesto here). Nightlife is presented here as a reaction to the atrocity of wartime, a multi-purpose place for debate in times of conflict, and surely a universal human need.

Nigeria’s Mbari Artists and Writers Club (with early sixties locations in Ibadan and Isogbo) appealed to the body and soul, with international music, dance and literature programmes—again, the visual designs here appear remarkably fresh, whether it’s actor/artist Jacob Afolabi’s expressive wood and lino cut images, or an array of titles (including A Walk in the Night by South African writer Alex La Guma) from the club’s publishing house.

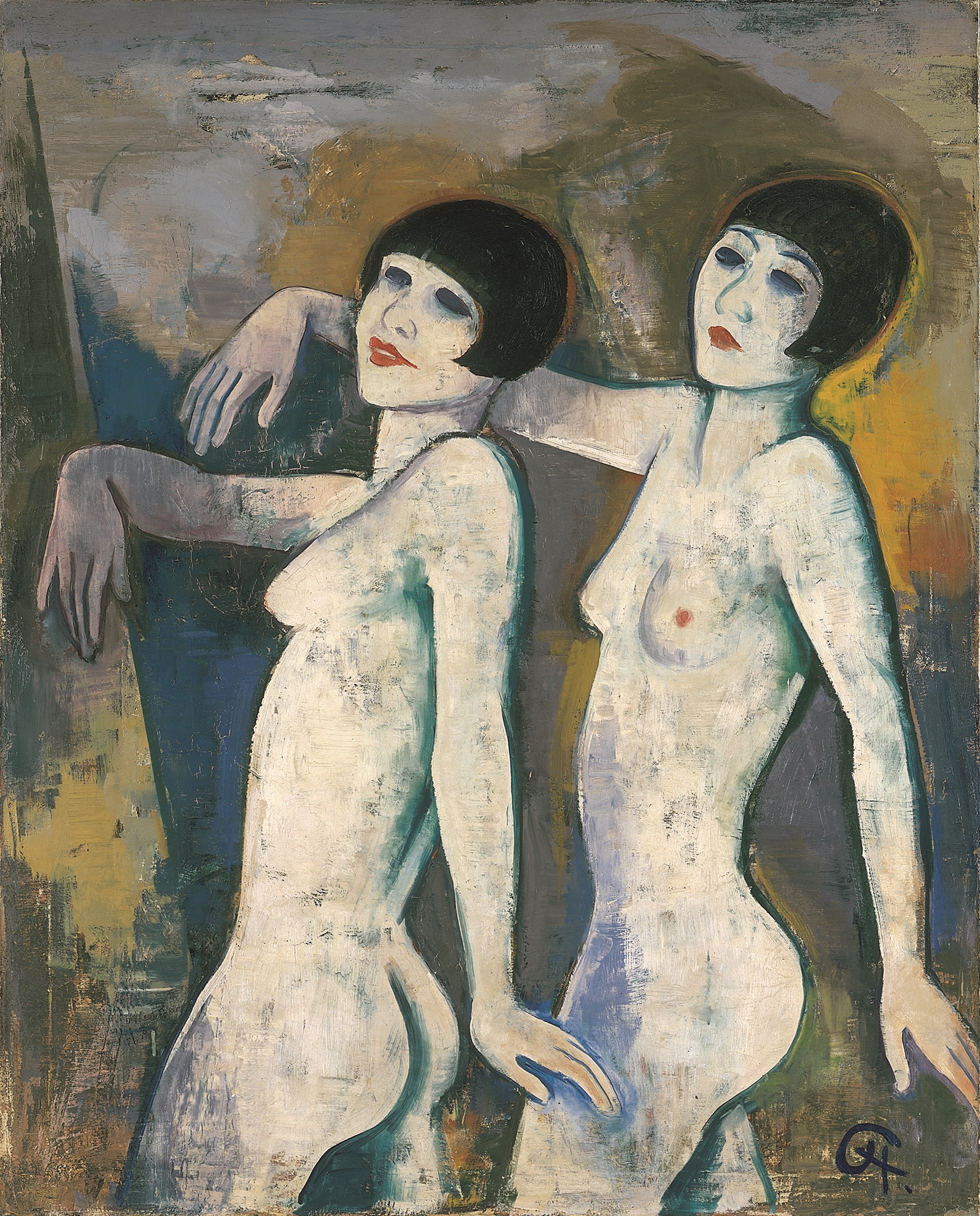

Nightlife is naturally a place where social and sexual boundaries are relaxed, or blurred in the shadows; there’s a wonderful frisson to the Weimar-era Berlin collection here, with highlights including the evocative female-centred paintings of Jeanne Mammen and Elfriede Lohse-Wachtler, and Curt Moreck’s droll 1931 Guide to “Depraved” Berlin. Such spirited, sensual forces have always been regarded with suspicion by the authorities; apparently, a German government slogan of that period warned citizens: “Berlin, stop and think, you are Dancing with Death”. We delight in these free expressions, yet we’re grimly aware of the horrific era that followed it; Lohse-Wachtler, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, would be one of countless artists persecuted by the Third Reich, ultimately murdered aged forty, as part of the Nazi “Aktion T4” forced “euthanasia” programme. It feels vital that her talent is remembered here.

- I’m a Clever Waterman, 1966 Collection Kamran Diba © Kamran Diba

One of the best aspects of Into the Night is that it digs deep—avoiding “obvious” hooks, and unearthing real treasures. There’s a devilish charm to the details throughout—such as Fortunato Depero’s lush, fiery designs for Rome’s 1922 Cabaret del Diavolo (slogan: “Tutto all’inferno – Everybody to hell!!!”), E Simms Campbell’s deliciously detailed Nightclub Map of Harlem (1934), or Theophile Steinlen’s slinky posters and dining menu for Le Chat Noir in late nineteenth-century Paris. Perusing the latter, I wonder who would want to feast on chateaubriand at a nightclub (but then, the closest I’ve got to club catering has been a 5am breakfast roll from the van that used to park outside Bagleys Warehouse). Dave agrees, adding that modern soundsystems send those basslines straight to your belly—Le Chat Noir’s live soundtrack (we hear Erik Satie’s elegant piano compositions) was presumably more attuned to digestion.

“Nightlife is naturally a place where social and sexual boundaries are relaxed, or blurred in the shadows”

The physical layout of nightclubs has always been significant—we descend into these hidden playgrounds, we sink into the booths, or we might watch the action from above, before we make our move. The Barbican’s ground-floor gallery goes enjoyably “immersive” here, recreating spaces including the Mbari club, and Strasbourg’s abstract “cinema-ballroom”, L’Aubette (1926–28); the latter design reminds us how integral balconies have been to many iconic clubs (although the balcony here appears frustratingly impossible to access—and it also gets me thinking of notorious New York 1980s/nineties “King of the Club Kids” Michael Alig

, who would urinate from the balcony of Disco 2000 onto the crowds below.

It’s a headrush to walk into the gorgeous tiled room of the Cabaret Fledermaus, intricately recreated from a 1907 postcard illustration. The exhibition also promises a programme of “after-hours” events, including live performance, talks and cinema, which should add further sparks to this excellent collection. Before we leave, another detail catches my eye—in a mesmerizing room dedicated to suspended mobile designs from Le Chat Noir. The initial light-and-shadowplay brings to mind nursery fairytales, before you realize that there’s a much darker edge at play; I remain quite haunted by the “suicidal Pierrot” figure, gently floating with a gun pressed to his head. The dance macabre recurs throughout club culture, across every continent and conflicted era—but “nightlife” is also an irrepressible force; its energy is never lost, regardless of fashion—it keeps moving and mutating, before our time and beyond it. Staying up late is in our blood.