Snapshot is a weekly series that zooms in on a single photograph to explore the context of an image, the conditions it is created within and its wider cultural impact.

In 1968, Enoch Powell gave his “Rivers of Blood” speech, now renowned as setting the precedent for a particularly hateful, political kind of racism. His words tore the country in two like the jagged end of a knife, as he criticised the so-called tide of immigration pouring into the UK; in actuality, this had stemmed from a post-war Britain inviting members of the Commonwealth to rebuild the country. Powell cited a letter he’d received from a Wolverhampton constituent, complaining of the immigrants moving into her street and the “white flight” that ensued. At a time when the Conservative party was scrambling for power, Powell weaponised the lives of people of colour to climb the political ladder, a strategy that has seen resurgence in the 2016 Brexit campaign, or even more recently in the media focus on asylum seekers.

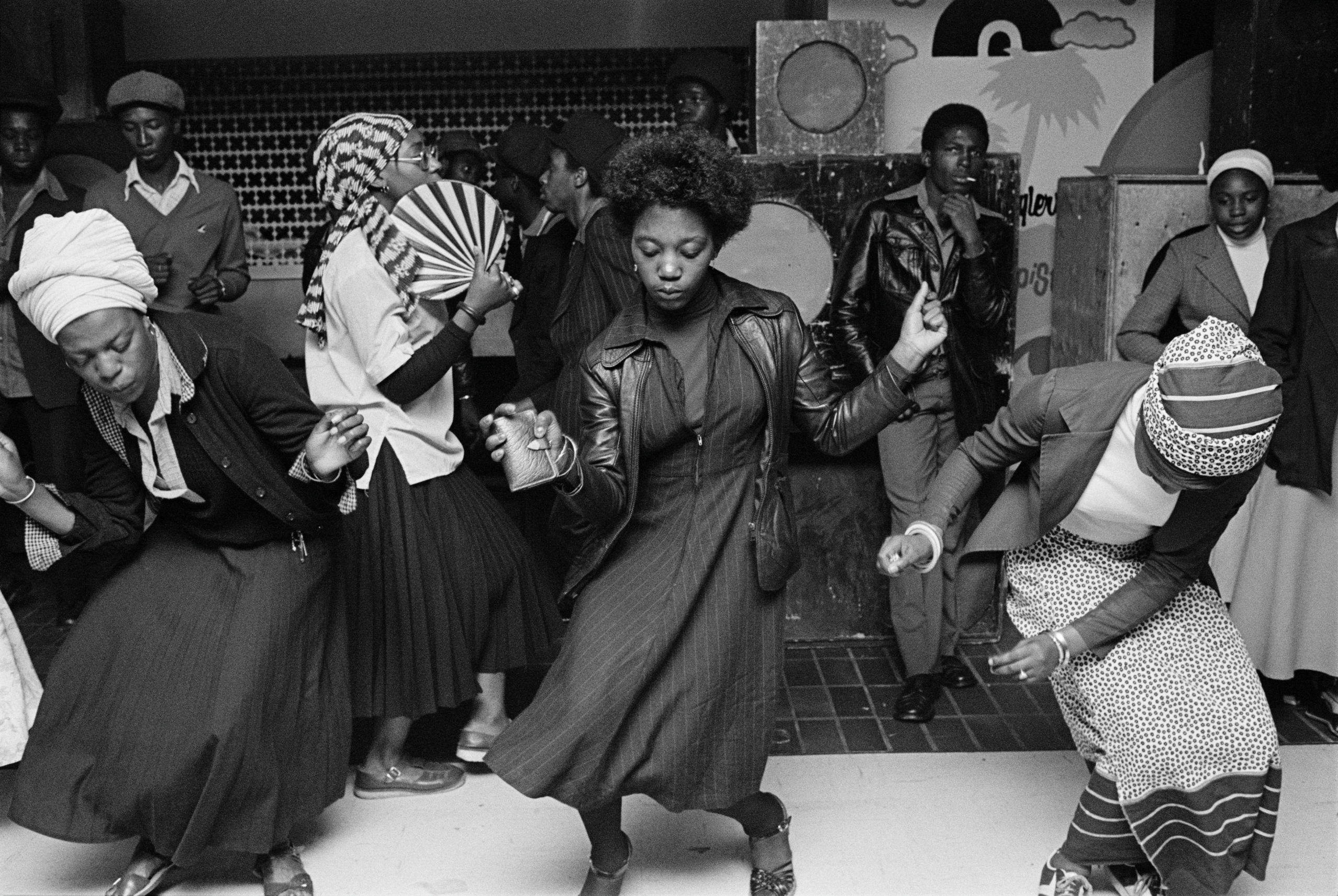

Fast forward ten years, and Chris Steele-Perkins, a photographer of British and Burmese descent, wandered into a youth club in Wolverhampton. Commissioned by the Sunday Times Magazine, he aimed to document what the city looked like, a decade after Powell spoke the words that ensured his removal from the shadow cabinet.

“Hardcore reggae was blaring from a soundsystem which took up most of the dancefloor, amidst packed bodies pulsing to the beat”

The image he captured is one that has been long heralded as a summary of Britain. Steele-Perkins describes the youth club in an interview with the Guardian

as being a “little island of energy” in the grey expanse that was Wolverhampton. Hardcore reggae was blaring from a soundsystem which took up most of the dancefloor, amidst packed bodies pulsing to the beat. There were a number of youth clubs which had formed in the area, mostly set up by churches, where young people gathered to “hang out, do some classes or just play pool”. The people pictured here were drawn to the reggae; Steele-Perkins recalls that they weren’t particularly young, but didn’t have many other places to flock to where they could dance to music they enjoyed.

Dance has its own kind of power, functioning like an algorithm. Music enters the body, limbs translate the sound into movement, outputting a co-ordinated, yet uninhibited set of motions. This is what Steele-Perkins captured so effortlessly, pressed between the heaving bodies, trying desperately to move as far back as possible to compose the best shot. He recalls the “degree of tension” in the club. “I had come up from London and I’m not African-Caribbean. These were slightly pissed-off youth and they weren’t dying to hang around with me.” They put up with him though, his camera shutter snapping away, and the result is an image which captures the spontaneity of the scene.

“Dance has its own kind of power, functioning like an algorithm”

Steele-Perkins was accompanied by Gordon Burn, a writer who was known for setting his words against the gritty backdrop of Northern England. Given the wider context of why they were there, the image is even more wonderful. To mark the tenth anniversary of Powell’s nonsensical utterances by shooting a picture showing immigrant communities not just surviving, but thriving, shoves the ultimate two fingers up at the establishment.

Despite the fact that at first, he didn’t love the image, Steele-Perkins admits that it’s one of his most sought-after prints: “It seems to have caught the popular imagination.” Ironically, the story was never published. The Sunday Times wasn’t printed for a year due to the print unions’ strike during the “Winter of Discontent”, and so the image holds even more of a transient quality, a piece of history that could have been lost if not for its popularity. If compared to contemporary movements, the photo feels Afro-futuristic in its depiction of Black freedom. More than ever, the work shows how community spaces induce feelings of joy, their presence even more essential against the backdrop of a city fighting against them.