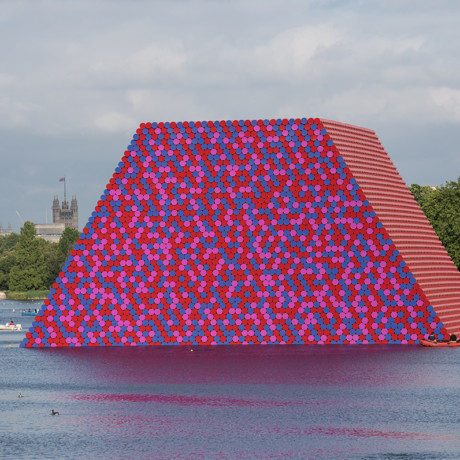

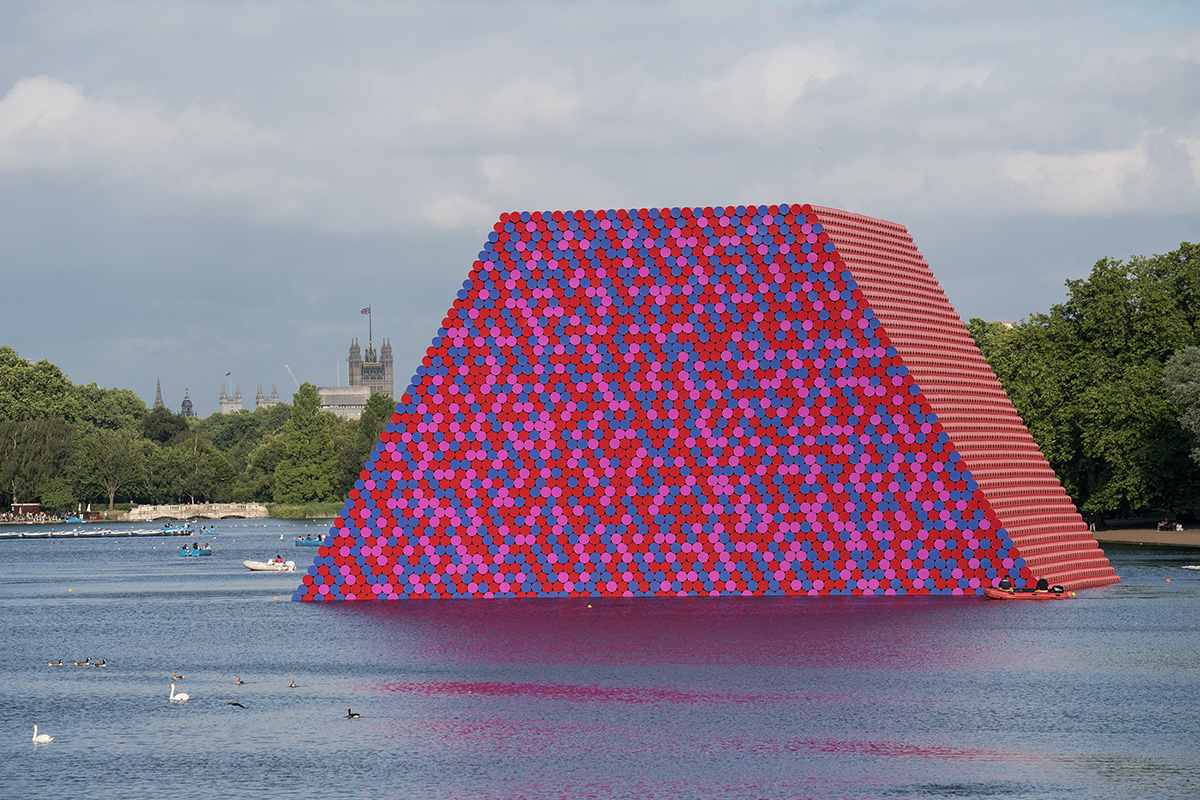

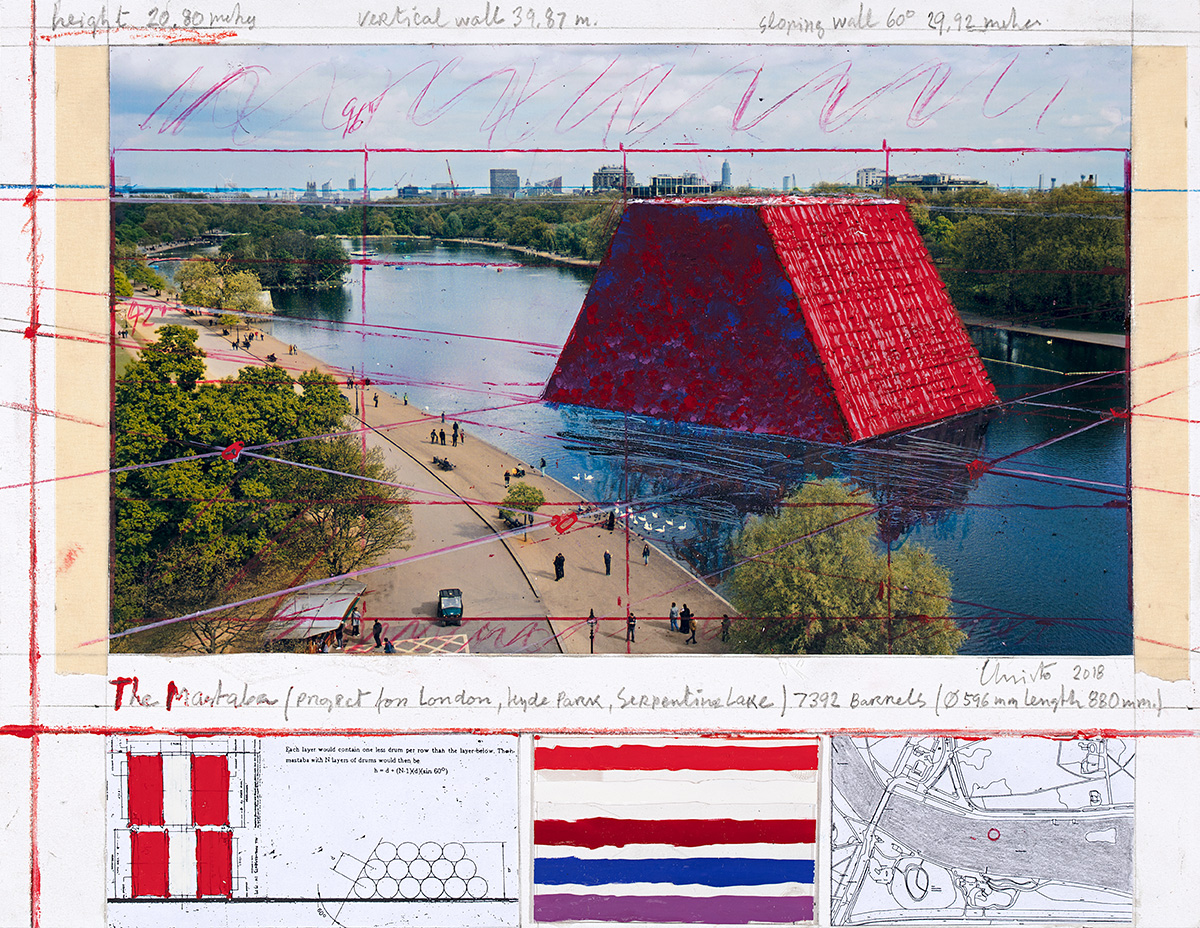

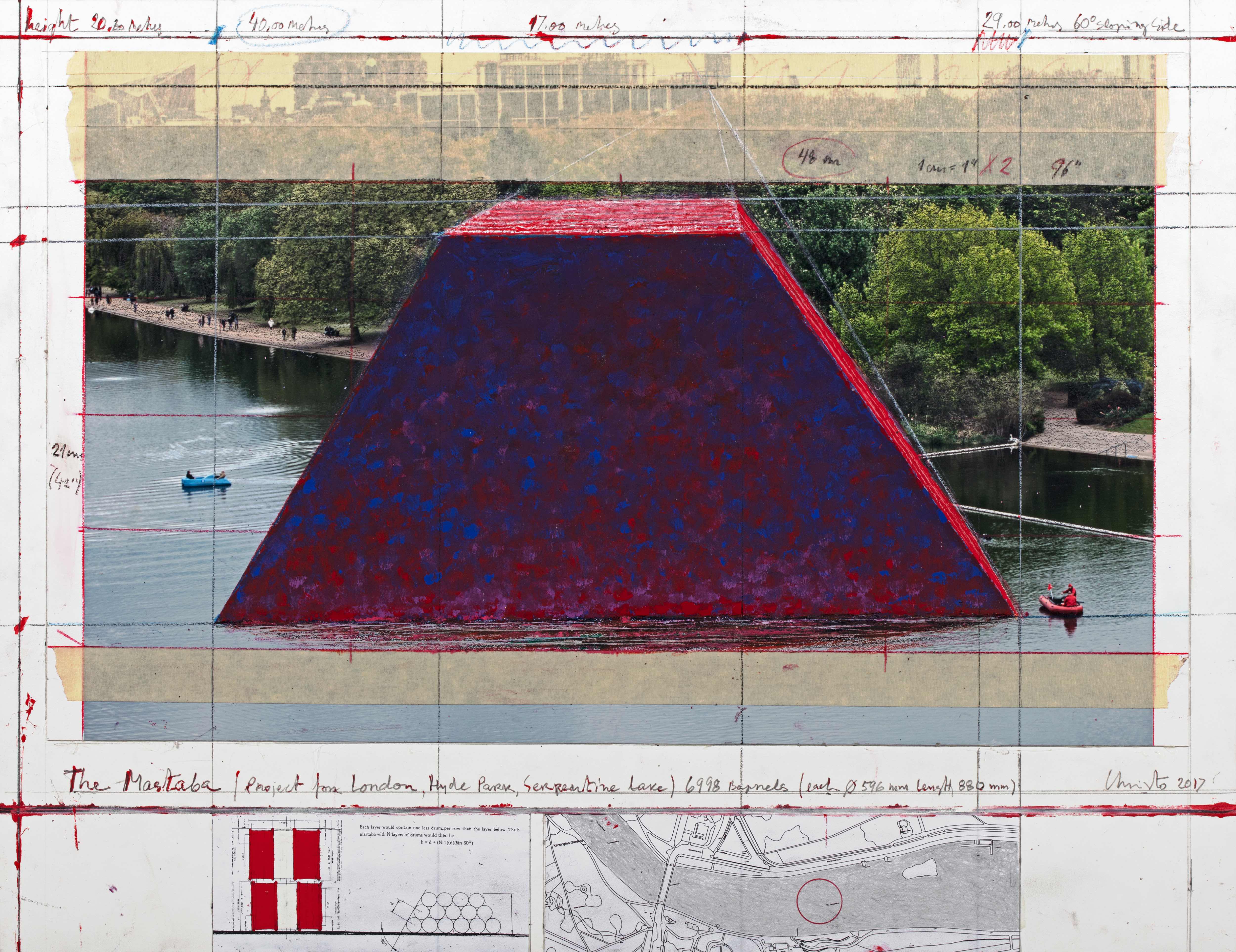

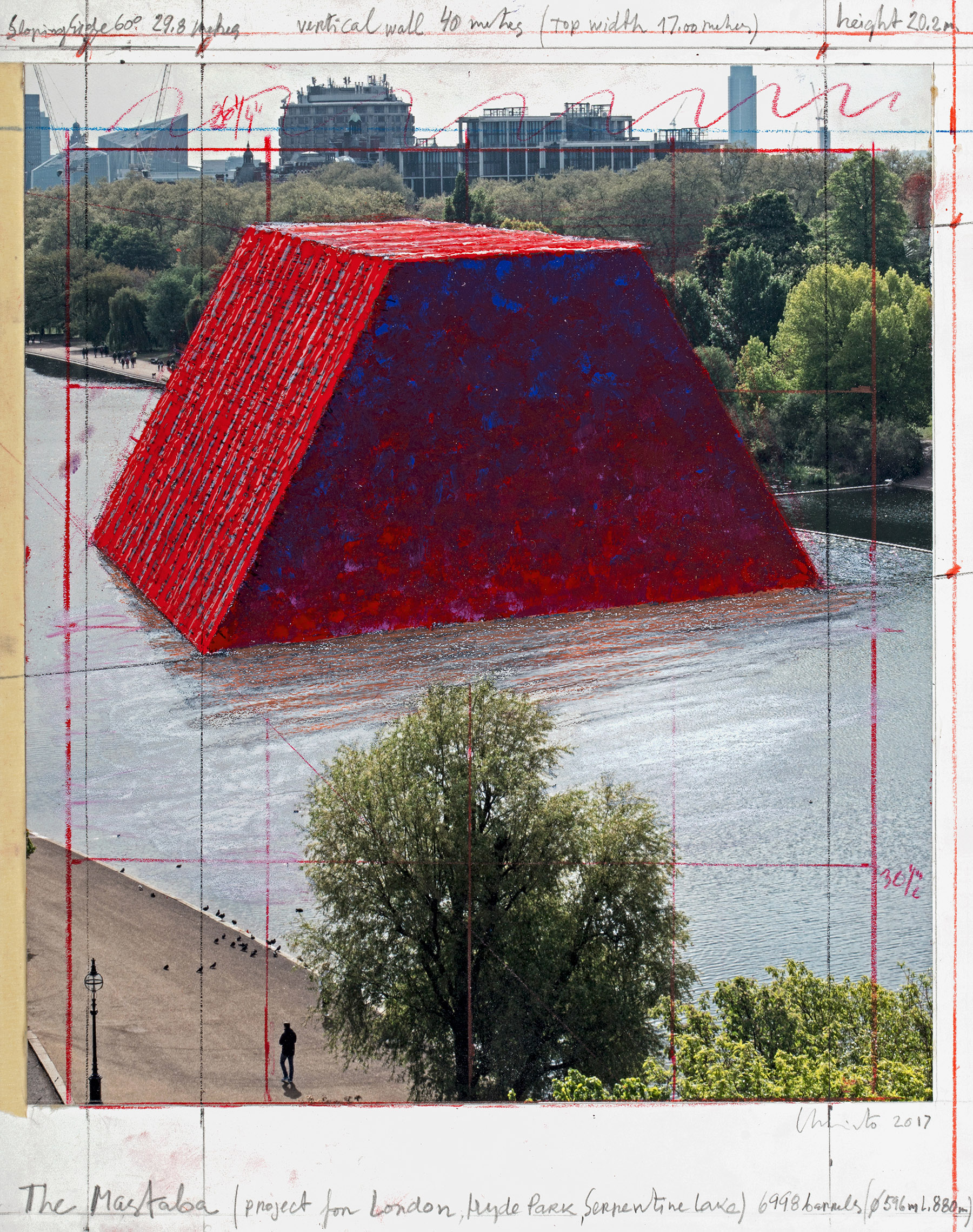

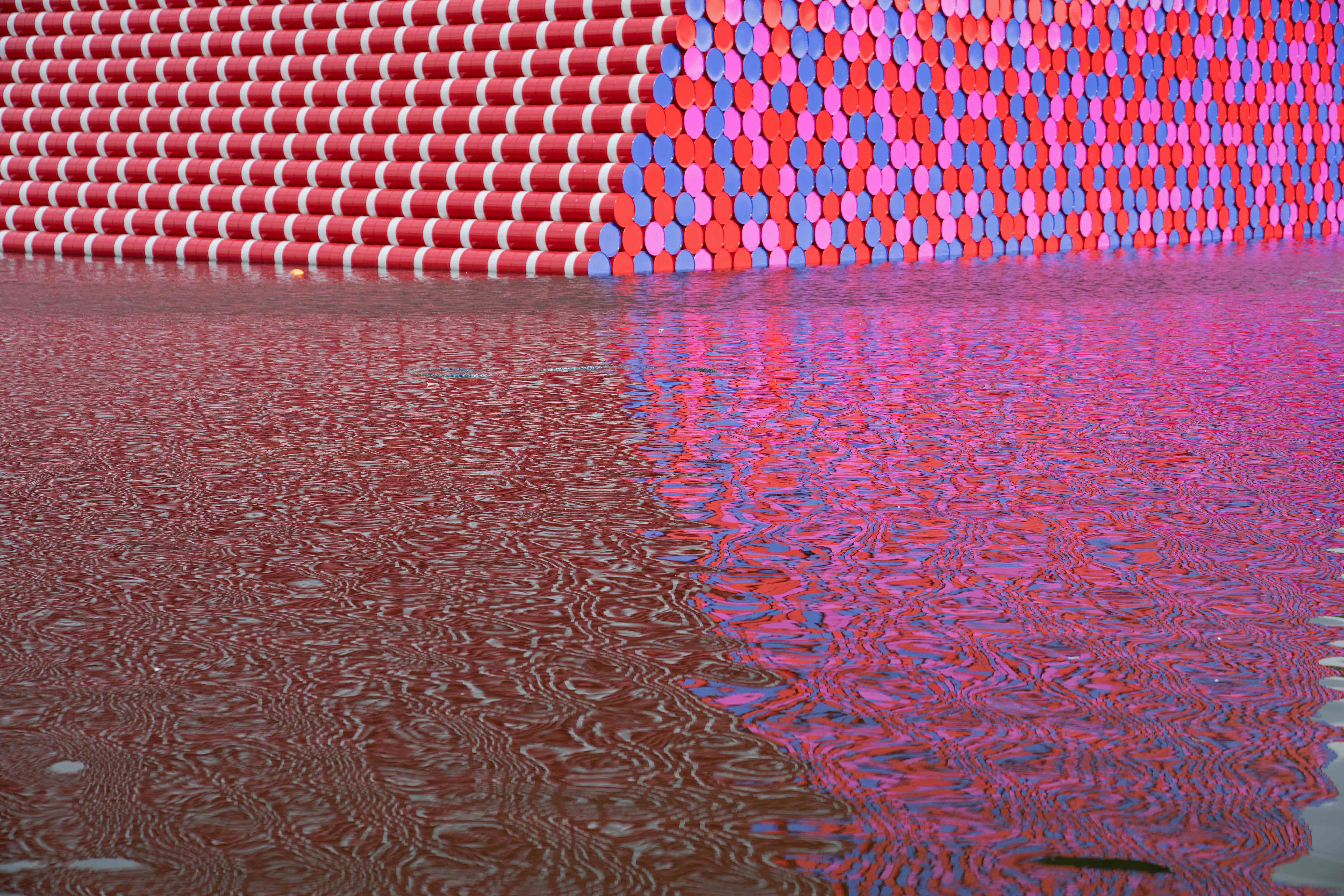

The London Mastaba, Serpentine Lake, Hyde Park, 2016-18, Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2018 Christo

It’s a beautiful summer morning as I make my way past the lakes and fountains, towards the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, where I’m to meet Christo, one of the few contemporary artists to be known only by one name. The wild heron balanced on top of the lakeside Henry Moore seems propitious. A collision between art and nature in an urban setting; a theme that runs deep through Christo’s work. The day before our meeting marked the opening of The London Mastaba, his temporary sculpture of 7,506 horizontally stacked blue and red painted barrels set on a floating platform in the Serpentine Lake, like a great pyramid.

I have my questions carefully prepared. What was the effect of his communist upbringing? Does he consider himself a land artist? How does he see his legacy? But, before I can get out the first question, he’s off—his sentences running as fast as a greyhound out of the starting box. This isn’t so much an interview as a private lecture by one of contemporary art’s most genuinely original artists.

“I owe everything to my parents,” he tells me. “My father was half Czechoslovakian, half Bulgarian. My mother, Macedonian. From the age of seven they encouraged me. I had private art lessons, real painting, real sculpture, real architecture. It was not so much that I escaped Communist Bulgaria in 1956,” he says, “rather that I went to live with relations in Prague. The world was chaotic. There was a lot of violence. Austria was divided. We feared WWIII. I’d done four years at the academy and the curriculum was very nineteenth century. We studied the decorative arts and even did two semesters of anatomy.

“I belonged nowhere. I was young and had never seen any real contemporary art so headed for Paris”

The course was eight years, but I left after four. I became a stateless person. I had no means, nothing at all. I had a “white passport”, a Nansen passport issued by The League of Nations. I belonged nowhere. I was young and had never seen any real contemporary art so headed for Paris where I did all sorts of odd jobs. It was in Paris that I met my late wife and life-long collaborator, Jeanne-Claude.”

I ask if he believes his comprehensive art education was of value. After all, his beautifully drawn plans have the precision of an architect’s project. “Well, the first critic who wrote of the wrapped Reichstag was an architectural critic. Space is such an important element in this work.”

“It’s an adventure, a drama of ideas but also very physical. I used to have huge arguments with Jeanne-Claude”

Where does he get his ideas from? They’re quite unlike anyone else’s. “I’m interested,” he says, “in the things we don’t know how to do, that engineers don’t yet know how to make. I work with a pool of people in the small hub of my nineteenth-century building. It’s an adventure, a drama of ideas but also very physical. I used to have huge arguments with Jeanne-Claude. We’d argue all the time. That’s how we developed our ideas. I’m not interested in modern technology. I can’t drive. I don’t use a computer. There is no elevator in my block. I spend six or seven hours a day standing in the studio. I like what’s real. I love the heat and air, wet and cold. I’m not very interested in the clinical space of the gallery. We call the thinking time the “software period”.

Educated as a Marxist, he set up a corporation to fund his projects largely from the proceeds of his drawings and other permanent artworks. He’s never had public funding and feels this gives him total aesthetic freedom. “Anyway,” he says, “in the early days no one was interested in our work.” He develops several projects simultaneously and emphasizes that he makes the work entirely himself and has no assistants. But he does need teams to help with the complex logistical planning and installation. It’s very expensive. The London Mastaba will have cost around £3,000,000. And it’s hard to get permissions. Twenty-three projects have been successfully made; forty-seven never happened.

“We work with the urban and the rural but in places touched by human habitation… Everything is based in the real”

Does he know what a work will look like when it’s finished? “Oh, yes. We find places to make them in secret, test the materials. For the Pont Neuf piece, we went to a small French village where the mayor owned a Monet and asked to wrap up his bridge.”

Does he feel connected to the tradition of land artists, such as Robert Smithson and his Spiral Jetty? “No. We work with the urban and the rural but in places touched by human habitation. We need the lamppost or church to give comparative scale. Everything is based in the real”.

How does a work evolve? “Well, in the places where people or collectors support us.” In the 1980s Miami was a place of race riots, refugees and violent crime. He and Jeanne-Claude arrived in town attracted by the flatness of the landscape, intending to dress the islands, built from piles of trash in Biscayne Bay, with hot-pink skirts. The result was lyrical and visually stunning. The idea was Jeanne-Claude’s, he reminds me, and it’s evident that he still misses her.

On 9 October 1991, their 1,880 workers began to simultaneously open some 3,100 yellow and blue umbrellas in Ibaraki, Japan and California. Why umbrellas? “Ah,” he says, “the work is like a diptych based in two of the richest countries in the world, but that have huge cultural differences. There’s a comparison in the space. Japan would virtually fit into California, which is much less densely populated. California is essentially flat, Japan mountainous. We started with the idea of shelters, but that was too difficult. Then tents.

We wanted to incorporate the idea of the nomadic. In the end it became umbrellas: roofs without walls. Yellow for California where the grass becomes burnt. Blue for Japan where there are rivers. We placed them near churches and gas stations. Real places. The umbrellas had bases where people sat. Families picnicked there. But in Japan, they took off their shoes. That’s a cultural difference. People think umbrellas were invented in Japan, but it was in Mesopotamia. Our umbrellas were eight meters wide and nine meters high. The size of an average two-storey Japanese house.”

Next, I ask about a typical Christo day. “I like to start the morning hungry. I might take a little yoghurt with garlic, a banana and some coffee. I need to feel edgy and alert, so I eat in the evening. The day is for creativity, the evening for classifying and ordering.” He doesn’t read anymore. “Because I’m running out of time,” he says. “The only thing that matters, now, is my art.”

And his legacy? Well, the work is all temporary, fragile. Like people striking a camp in the desert. It’s there one minute, then taken down. “In the end, what do we know about ourselves? What remains are ruins and memories. We can make a sort of archaeology, but reconstruction isn’t real. The computer chip is the most reliable way of recording what’s real. These will give the only true records of the present in the future. But I don’t like nostalgia. I love life too much. I’m not interested in retrospectives. I have too many new projects in mind.”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Barrels and The Mastaba 1958–2018

At the Serpentine Gallery until 9 September

VISIT WEBSITE