Architecture can’t save the world, but it can lighten the load of existence in fraught times—according to the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator duo Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Irish practice Grafton have assembled the complex yet poetic and ultimately optimistic Freespace, in which over one hundred invited architects and sixty-five countries have contributed exhibitions. Freespace celebrates the spirit of generosity in architecture spanning all scales and typologies of our built environment and natural resources, from the democratic beauty of an aesthetically pleasing wall to the supple cast of moonlight across a body of water.

In celebrating and questioning the democratic potential of architecture, this year’s Biennale is particularly sensitive to themes of embodiment and inter-species relationships. Viewing architecture as a connecting thread between humans and the landscape, ecologies and emotions, Freespace goes beyond literal definitions of architecture in its attempt to bring to life some of these complex conditions, made all the more salient in light of our current planetary and political climate.

It is a sliding scale between nature and culture. Some participants, such as the UK-based Alison Brooks as well as the Swiss and Scottish Pavilions, have produced projects that are fully embedded in the urban environment: a condition that will affect two-thirds of humankind by 2050. In the sweeping expanse of the Arsenale, a sixteenth-century shipyard measuring 317 metres in length, Brooks has devised an indoor playground of four details from her pre-existing projects, blown up to an inhabitable scale. Tricked out with mirrors and other spatial optical illusions, these “totems of free space”—taking the forms of passages, façades and rooftops—together become an “urban stage that represents the theatricality of thresholds, serving as a celebration and elevation of everyday encounters”, according to the architect.

Meanwhile, Switzerland has created a riff on the rental home stereotype that skips the typical existential terror of open houses for an unpredictable, confounding and ultimately delightful uprooting of spatial logic. A true fun home filled with oversized kitchen counters as well as shrunken rooms, trick doors, pill-sized power sockets and children-only cubbyholes, it encourages a second look at the unremarkable aesthetics of standardized living spaces and still maintains a critical edge despite its capacity for play.

Far away from the main drag of the Biennale, architect Lee Ivett of Baxendale Architects and curator Peter McCaughey have created what they refer to as a “living library with the right degree of wrongs”. Filling the garden of the Palazzo Zenobio with a joyful outdoor playground ripe for transformation by its users, drawbridges, ladders, deckchairs and a DJ booth become a modular “free space” that can be added to and deconstructed by locals.

During my visit, I watch as one corner of the L-shaped playground is temporarily transformed by a gaggle of hyperactive seven-year-olds into an elaborate game of ropes. Kids run rampant in the sunshine as adults stretch out on recliners, sipping prosecco and generally recuperating from the madness of the Biennale. We take multiple breaks from the interview as the curators lend a hand in parallel events, from coordinating a parade to helping a Swiss student organize a parallel exhibition elsewhere in Venice; soon, the meaning behind Happenstance starts to speak for itself.

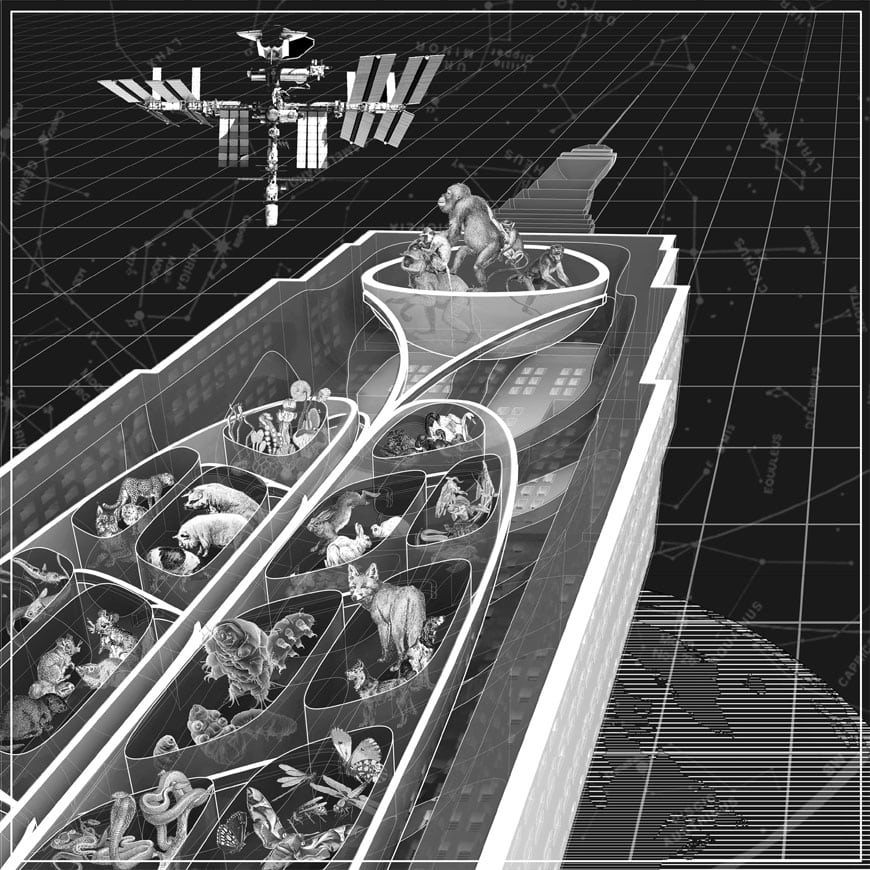

Others ditch urban digs for proto- and post-human landscapes in order to delve into topics of climate change and sci-fi survival strategies. In the US Pavilion, outer space enthusiasts Design Earth have produced Cosmorama, which consists of three semi-fictional scenarios that illustrate some of today’s most salient political and environmental concerns. Backlit illustrations depict apocalyptic narratives of the near future, from privatized space race legislation that stems from neoliberal entrepreneurialism narratives, to mining nearby asteroids for non-renewable resources and a planetary ark that proposes to save endangered species from the uncertain future of planet Earth.

“Freespace celebrates the spirit of generosity in architecture spanning all scales and typologies of our built environment and natural resources”

Australia has filled its sparkling new building with an arsenal of indigenous plants, while Argentina has created a trippy hall of mirrors populated by greenery. Meanwhile, on its Via Giuseppe Garibaldi outpost, Lithuania has entered the post-human architecture party in full swing this year with The Swamp School. The country’s debut exhibition in Venice ramps up the political and pedagogical potential of swamps-as-metaphor, using Venice’s own geographical distinction as a lagoon as a case study.

Back in the cavernous expanse of the Arsenale, padded floors, a twisting abstract model, ambient lighting and the sound of cracking ice transport visitors to Dorte Mandrup’s large-scale ice age installation at the back of the complex. Conditions underscores the inhospitable geography where Inuit and Europeans (Norse) met for the first time, some 200,000 years ago. As an artificial storm kicks up and the pale blue landscape plummets into dark winter and then lightens into an infinite summer, Conditions carves a new joy and intimacy within this chance encounter. Mandrup’s built structure on which Conditions is based, the Icefjord Center on the west coast of Greenland, takes the backseat in favour of this imaginary history of humankind. Instead, the poetic and supersensory installation of humanity’s victory against the “superpower of nature” provides a refreshing contrast to the many doomsday narratives dotting the Biennale this year.

“The human essence of architecture—both its playfulness and perils, its elemental past and increasingly complex future, its manicured and untamed tendrils—emerges”

Finally, the Dutch and Cruising Pavilions are two main players in a roster of special exhibitions that dive deep into the embodied landscapes of labour, technology and culture, as well as the subcultures existing beneath the surface. Marina Otero Verzier, head of research and development at the perennially trendy multidisciplinary research institute Het Nieuwe Instituut, has produced an equally eye-popping project titled Work, Body, Leisure that takes a playfully serious approach to the fluctuating conditions of labour and the pressures placed on the body in the wake of automated technology. A bright orange locker room-like interior with multiple disguised doors opening out into separate research projects including a survey of virtual body standardisations by Simone C Niquille. The Architecture of Sex Work in collaboration with Amsterdam Museum and the Foundation for Responsible Robotics, as well as a performative Q+A Bed-in with artist Beatriz Colomina that recreates Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s famed Bed-In for Peace (1969) in Amsterdam. While legible in parts, the overall impression of the Dutch Pavilion is a loud and chaotic assemblage of concepts that are never able to join animatronic hands.

Still, the Dutch Pavilion’s most interesting component includes a range of unrepresented and heterogeneous bodies that is conspicuously absent in the Cruising Pavilion, despite its claims to do just the opposite. The four curators, Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault and Charles Teyssou, slammed the Biennale’s directors for failing to consider the “heteronormative production of space itself”, warning of an unofficial intervention to come. Yet their attempt at producing an alternative queer space within Spazio Punch Gallery located on the island of Giudecca was effectively a black-out set of Swiss cheese-style scaffolding in which “every hole is a goal”. With a dark set-up that conceals the lack of content and renders the rest of it mostly impossible to read, the Cruising Pavilion limits its understanding of such alternative spaces to a dimly-lit private party.

For all the requisite poetics of this spirit of generosity in architecture, the 2018 Biennale nonetheless gets down to business with the relational and embodied qualities of the discipline. Rather than mediate these separate manifestos—which wind from the early days of human civilization to the banality and wonder of contemporary life to bizarre sci-fi narratives of alternative futures—Grafton has left a “free space” that works across scales and time. The human essence of architecture—both its playfulness and perils, its elemental past and increasingly complex future, its manicured and untamed tendrils—emerges across its ancient palazzos, pavilions and exhibition halls within this surreal city, both Biennale-bound and beyond.