Writer Shaquille Heath talks to artist Lonnie Holley about his approach to encountering the objects that surround us, the concept of ‘debris,’ and his current exhibitions in London and St. Petersburg.

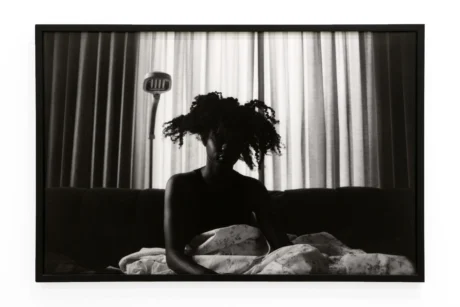

BLUM Gallery (LA/NYC/Tokyo), and Edel Assanti Gallery (London). Photo: Truett Dietz.

As an itty bitty thing, hardly even two, Lonnie Holley was attune to seeing. From his perspective, the world was full of fascinating objects, but hardly anyone else saw them that way. “You can imagine me crawling around at the fairground. Just crawling around on the ground,” shared Holley. “And you can imagine me having to look up and watch what was falling down from human hands as they threw stuff away. Everything dropping. And left for somebody else to be responsible for picking up.” In all of the objects discarded onto the ground around him, Holley saw assets. You might find yourself wanting to say “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” but the sentiment is incompatible. That’s because the value system that Holley reckons with is widely different. The word “treasure” alludes to their being some sort of orchestration of wealth, and within Holley’s system of treasures, money only feels like a real consideration when it meddles to keep people apart. Lonnie Holley and his oeuvre works strictly in the vein of putting us—and the things we foolishly separate—back together again.

Holley is a renowned blessing to the art world, his creativity spanning an artistic practice that includes sculpture, painting, performance, drawing, film making, and music, creating work since the 1970s. The bulk of this practice stems from Holley’s collection of found objects. “The parts of what I saw that affected me the most was trash, garbage, and debris. The things that humans threw away. Where were they going to go? What were they made of?” In our discussion Holley made it clear that this interest in the discarded was something of a family affair. “I remember traveling with my grandfather and watching him. He ran across these objects. He looked upon the object. He saw that he could use it then or later. He collected it and he put it on his oxen and wagon. He carried it home to put it in his stockpile. Someone else looked at it as a junk pile or a trash pile. But, what I have is mine. What he had was his. His example was I saw how he was building a 16 room house. And how every stone that he might have picked up was going to be a part of his foundation. He put together a foundation. So…maybe I’m still putting together a foundation.”

It’s a profound thing to hear an artist who has been making work for four decades say. But talking with Holley is a sagacious lesson that the universe is intentional with every step we take, even when those steps are filled with pain and hardship. From crawling around fairgrounds, to being handed around burlesque clubs, living in a whiskey house, walking through sewage pipes, being hit by a car, to having to endure harm at the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, and more and more and more. It’s a peculiar and haunting path, but it’s one that made him observant. “The best part of what I was noticing was the pictorial. The pictures from the Bible. Because I couldn’t read and write that well. But nothing was ailing my sight. It was nothing ailing, me seeing what the contributions were by our ancestors—all the way down the timeline, as far as there were pictures orchestrated.”

Holley talks about his life so nonchalantly that hearing him speak can feel a bit shocking. It feels that there’s no way that someone who has endured that much grief and heartbreak should be as whole and inspired as he is. “You got to think about me being a child and with the kind of brain that I had. I was probably just goin’ places all the time, building my interest in material things. Excuse me, but they probably would have called me a bad-ass child! Haha!”

There are so many articles and stories that exist in the world outlining Holley’s traumas and recounting his painful path. I couldn’t help but wonder if he ever became sick of replaying these memories over and over. Of course, he couldn’t feel more opposite. “I think our togetherness and our conversation together is going to help more humans on this planet know that we do need to take time to figure things out. But figuring them out and leaving them in our head is not going to justify anything for anybody. We have to write about our experiences and that, I couldn’t do…But it’s just so fortunate that I am living in a time where I am needed the most. I’m needed the most right now. Not doing the most for self glorification. I’m not trying to glorify myself. My grandmama had already taught me about, ‘you ain’t wear but one pair of shoes off in your grave. I don’t care how many pair of shoes you get, you’re not going to wear, but one pair in the grave.’”

Holley’s work is absolutely needed. Currently he has a solo exhibition on view at the Camden Art Centre titled All Rendered Truth. “About what?” I asked. “About what? Mostly about our faults,” he shared. “About these different types of wires and things corroding. And not behind our back. Because we don’t notice. It’s put between the walls of most of our homes, the electrical wires that we depend on…but we keep on plugging stuff into those wires.”

The strengths that lie in assemblage artists is their ability to see value for exactly what it is. It is both a primitive and apocalyptic view at once. Looking back and looking forward. Realizing that as humans, our ideals are so misaligned. Holley’s work has the purpose of reminding us that what we depend upon—the things that keep us alive, healthy, satisfied and content, is far removed from what we desire, dream, covet and crave. “These were my contributions to any part of the art world. Is that I had allowed others to know what a piece of wire is… galvanized copper, brass. What a piece of tin is…galvanized, steel, aluminum, brass, platinum. What we believe in is silver, gold, and diamonds.” What we need is not given its proper merit. “You know, you got a ton of diamonds—you’re rich. If you got 50 tons of gold–you’re filthy rich. You understand what I’m saying? But if you have 50 tons of particle debris out of the ocean and the sea, you’re not that rich.”

This line of questioning and examination extends to Holley’s other exhibition on view at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg in an exhibition alongside the works of artist Lizzi Bougatsos. The two share thematic commonalities between their works with the use of found objects, but also in their focus on sustainability and environmental conservation. “My gathering of materials before rendering that show, were already materials that were talking about the water’s edge. Getting those things together with it in mind that this show needs to be about our hazardous waterways. Because I’m not kidding with you, and it almost makes me cry… every hurricane, every tornado, every storm, and the storms and the tornadoes and hurricanes are getting worse—they are leaving behind so much debris… And we cut it up into little things and we send it to the city landfill.”

For decades Holley has been making work to help humans see that everything that we often need is already right before us. That the rat race and the hustle is an unnecessary exploitation of the powers that be. That our desire to have our humans needs—a safe place to live, a warm plate of food to eat, someone sweet to pass the time with—isn’t as much as we think it is. “I love the song, It’s a Thin Line Between Love and Hate. Sometimes a garment that we loved, it gets something on it, and we don’t love it any longer. Our shoes get too dirty, and we don’t love them any longer. The dish that we was eating, we taste it and it don’t taste right, because we tasted something else that tasted more righteous. And we don’t love it any longer. A thin line between our love and what we hate is growing enormously. It’s growing out of control.”

It’s about as easy to wrap up a conversation with Holley as it is to leave a gallery full of his work—which is to say, it’s not easy at all. One piece of wire leads you to a face that feels familiar, that leads you to a piece of driftwood that brings up the memory of that perfect beach day, that leads you to a burnt out radio that looks like the one you had during the worst summer of your life. He speaks in this same manner, connecting all his thoughts through memories and anecdotes that punctuate the essence of his work. I thanked him deeply for all the words he was willing to share and he left me with this: “I really like that this is a project called ‘Elephant,’ because of the elephant and how thankful they are, and all the memories that serve them best over their growth. I did a piece called 144,000 Elephants, and I mentioned that at Camden. They asked me why did I think of 144,000 elephants? I was talking about elephant power. The strength of an elephant. How the female elephants act down to children. How the male elephant grew to be so strong. My memory factor is so strong, and I thank you for choosing me as an elephant.”

Words by Shaquille Heath