At 7.27pm on 17 June 2003, more than 100 people gathered in the home furnishing section of Macy’s department store in Manhattan. They surrounded a $10,000 rug and informed the salespeople that they were looking to purchase a “love rug” for the free-love commune they shared. Precisely ten minutes later, the crowd dispersed.

This event is widely considered to have been the very first flash mob, a phenomenon defined by Collins Dictionary as “a group of people who arrange by phone or online to meet suddenly in a public place to do something for a short time.” The Macy’s mobbers were summoned in advance by text and email chains, instigated by an anonymous ‘Bill’, who later revealed himself to be Bill Wasik, then an editor at Harper’s Magazine, now the editorial director of The New York Times Magazine.

Picked up by blogs, chat rooms and mainstream media, flash mobs spread like wildfire that summer. Wasik continued to organise events in New York, such as the 500 mobbers who stormed the Toys R Us in Times Square and cowered beneath the store’s giant animatronic Tyrannosaurus rex. In Rome, 300 people flooded a music and bookshop asking for non-existent titles. In Berlin, 40 people took out their mobile phones in the middle of a busy street, shouted “Yes, yes!”, and then applauded.

A timestamp in the history of telecommunications, Wasik has since described his original flash mobs as “a demonstration of what the technology of internet chain emails and text messaging could do, and a demonstration of social networks.” It was also, he said, a critique of hipster culture: “Part of what I was trying to lampoon with the flash mob was the idea of the ‘next big thing’. It was like I was creating the next big thing and saying, ‘Well, I’ll tell you what the next big thing is, it’s nothing. Let’s all get together for nothing at all’.”

True to the short-lived nature of the mobs, and the fads they imitated, the craze was declared over before the year was up. But while flash mobs in their original form died out, the phrase did not. “The term ‘flash mob’ was invented to describe the giant, absurdist meetups that I and others were doing, where most people had no idea what was going to happen until they showed up,” Wasik explains today. “But then people started applying the term to the kinds of things that Improv Everywhere was doing, where a group of people planned an elaborate show for an unwitting audience.”

Charlie Todd, who in 2001 founded comedic performance art group Improv Everywhere to create “unexpected scenes of chaos and joy in public spaces”, believes this shift occurred as a result of one particular mission. Filmed in 2007 and uploaded to YouTube in 2008, it involved over 200 participants standing frozen for five minutes in New York’s Grand Central Terminal.

“I think our Frozen Grand Central video is really what introduced the flash mob 2.0, without me ever using or liking that term,” says Todd. “That was the first truly viral video that we ever had. Within weeks, hundreds of people were freezing in place in train stations, plazas and campuses around the world. It was everywhere.”

“Within weeks, hundreds of people were freezing in place in train stations, plazas and campuses around the world. It was everywhere”

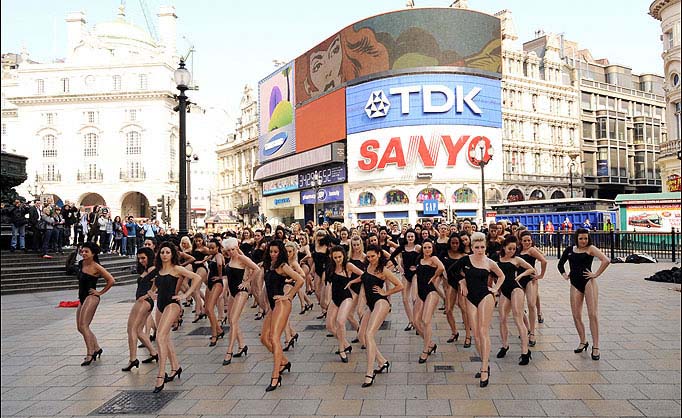

The term “flash mob” has since become a catch-all for any seemingly spontaneous stunt or performance in a public space. The most common are flash mob dances, which took off in the late 2000s in shopping malls, squares, train stations, and even prisons. One hot-spot was London Liverpool Street Station, immortalised in flash mobbing history by the 2009 T-Mobile Dance advert, which cleverly harnessed the flash mob’s reliance on mobile communication.

In the early 2010s, when everything online was “EPIC” and what happens next was always guaranteed to “SHOCK you”, organisations like Club Mob popped up, offering to create bespoke flash mobs for special occasions. More cringey than any impromptu musical theatre number were the flash mob proposals that played out in busy high streets to an inescapable soundtrack of LMFAO’s Party Rock Anthem or Bruno Mars’s Marry You (grounds for a breakup rather than an engagement, in many people’s opinion).

Whereas Wasik’s unfilmed originals demonstrated the power of social networks pre-mob (growing organically through the forwarding of texts and emails) the virality of these later “feel-good” flash mobs occurred after the event, once they’d been filmed, edited and posted on social media. Nevertheless, they still surprised the public.

“The virality of these later ‘feel-good’ flash mobs occurred after the event, once they’d been filmed, edited and posted on social media”

“Flash mobs are designed to disrupt the normal, to shake up people’s routines, expectations and attitudes,” says marketing professor Anthony Patterson, who traces them back to the Situationist International (1957–72), an avant-garde movement that strived to disrupt the capitalist systems that govern everyday life. It’s ironic, then, that flash mobs have been co-opted by those very systems for promotional purposes, from Ford Motor Company’s 2005 “flash concerts”, part of a campaign to sell its Fusion sedan, to Ray-Ban’s plaza performances.

Even so, Patterson believes that flash mobs are “powerfully emotional things”, especially when used for protest. These include the democracy activists who gathered to eat ice cream in October Square in Minsk in 2006 to subtly undermine Alexander Lukashenko’s regime; the One Billion Rising flash dances protesting violence against women, and the flash-mob techniques of pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong in 2019.

At the height of the pandemic, flash mobs of every kind became an alien concept. Videos of crowds dancing en-masse in front of lingering commuters felt impossibly distant and dated. TikTok, which took over as the prime destination for quick-fire dance routines, reintroduced the flash mob on a smaller scale last year, with @rony_boyy’s choreography to Like Yhop being performed in theme parks and underground stations, and the “Flash Bobs” of entertainment collective @bobsdanceshop.

“The craze was declared over before the year was up. But while flash mobs in their original form died out, the phrase did not”

“In the context of Covid, I think the viral qualities of flash mobs are precisely what enables them to mutate and adapt to all conditions, contexts, and uses,” says Georgiana Gore, professor of anthropology of dance. “They can be used for any purpose by anyone, not just professional performers or those with financial capital. Unlike conventional street theatre, anybody can join in and become a star for a day.”

While our current understanding of the flash mob has mutated far from Wasik’s love rug stunt (swapping cynicism for polished choreography, commercialism, and a healthy dose of cringe), when done well the power of collective spectacle remains.

“As pandemic conditions improve, I hope that we’ll see a resurgence of these kinds of projects around the world,” says Todd. “I think it’s important to be in a crowd of strangers and create something bigger than yourself.”

Madeleine Pollard is a Berlin-based journalist specialising in culture and current affairs

Love contemporary art stories? Check out our back catalogue of Elephant magazine, as well as the latest issues, at Elephant Kiosk.

Contemporary Classics

From memes to emojiis, Elephant explores the intersection between art and pop culture

READ MORE