Damián Ortega’s studio is tucked down a quiet street in Tlalpan, a pretty colonial village with cobbled streets on the southern edges of Mexico City’s unwieldy urban sprawl. On my arrival he whisks me off to a warehouse a couple of blocks away where he is working with an engineer to test the resistance of a planned 5.5 metre sculpture composed of precariously stacked hollow bricks, a commission for a pair of Napa Valley collectors. Once the monument is built, he will take a sandblaster to it. “These figures become really elastic, organic, more sexy, irregular and the contrast is interesting,” says Ortega. “The net of the brick squares creates a very orthogonal, rational structure and with the sand it’s an organic process of deconstruction. I like to play with erosion to show the fragility, how rigid things are transformed into a skeleton.”

“These figures become really elastic, organic, more sexy, irregular and the contrast is interesting”

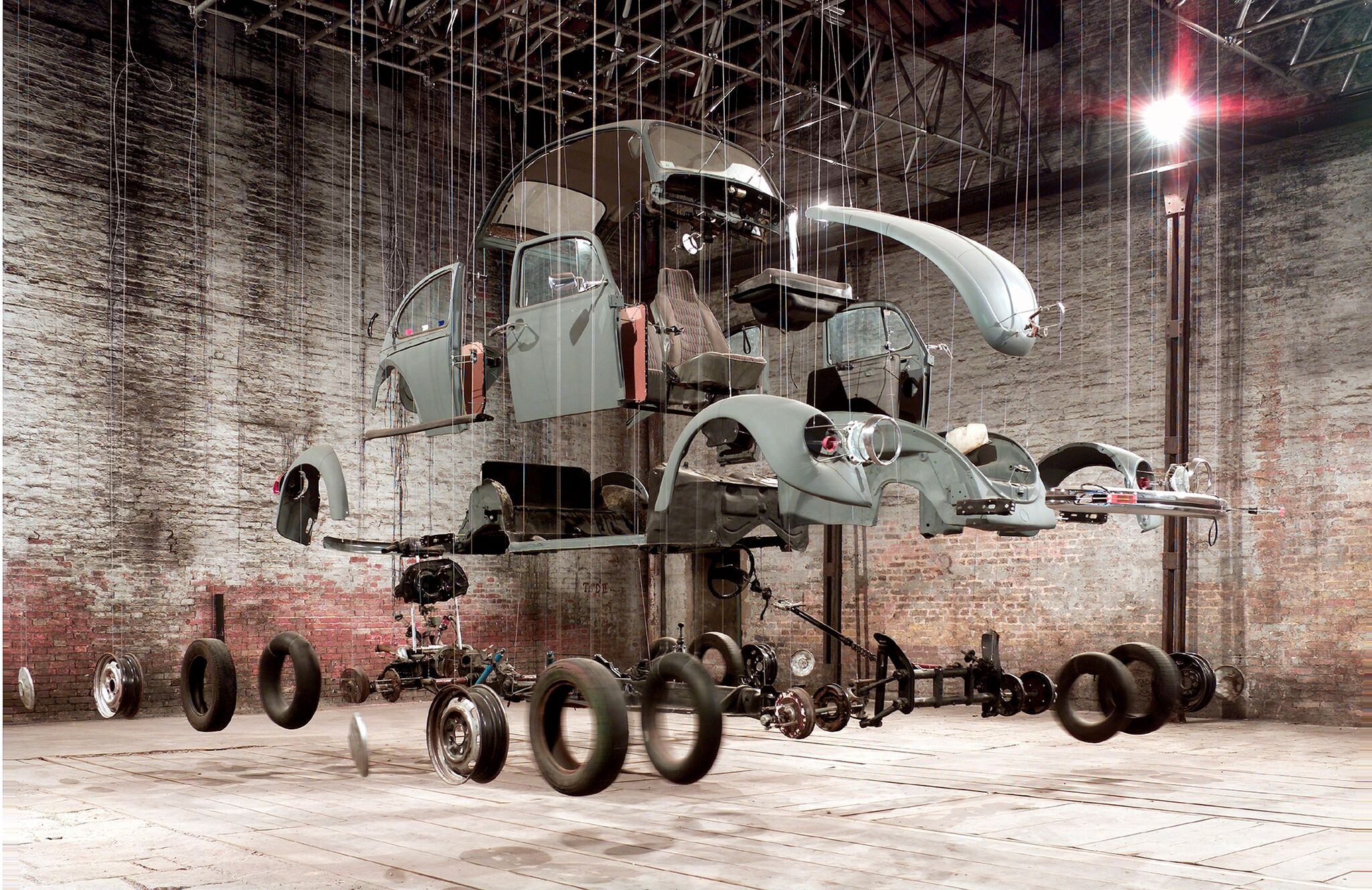

Although he also works with photography, performance and video, Ortega is most renowned for his talent in conjuring visual poetry from quotidian materials in his sculptures. He has made geometric constructions from the humble tortilla, gravity defying sculptures from chairs, a spinning tower of teetering petrol cans and he has looped cement into knots. Most famously, he dissected a Volkswagen Beetle, which he presented at the 2003 Venice Biennale in fragments suspended mid-air, resembling a mythical machine-beast descended from some industrial galaxy. In the corner of the warehouse, I am excited to see not that Beetle but a rusty white cousin that starred in two of his subsequent performative works.

Remembered in Germany as the “People’s Car” conceived by Hitler, the VW Beetle has quite different associations in Mexico, where it was manufactured from 1962 until 2003. The beloved bug became a symbol of freedom and independence for many Mexican families, including Ortega’s, thanks to its cheap price and availability of parts. So his “blown up” Beetle, with its hippy title Cosmic Thing, touched a chord for many. Moreover, his dismantling of the vehicle imbued it with a kinetic dynamism way beyond the sum of its parts. “I think it was a kind of revelation,” agrees Ortega, “because you conceive the world as a unity, enclosed, and [here] you can see all the elements of the system connected to each other. You realize the diversity, the imagination, the long process of becoming something you use every day but that was also a marvel.”

The artist has employed a similar logic of fragmentation with other works too, the result of his childlike curiosity about the inner workings of things. His 2007 installation Controller of the Universe comprised a violent maelstrom of suspended work tools—hammers, saws, rakes, axes, chisels magically frozen in motion in the process of exploding outwards. “I like the idea of breaking to analyse. I used to be more calm and watch my brother opening and destroying all the kitchen machines while my mother was screaming. And after years, I did it professionally,” Ortega laughs.

He uses humour in a similar way. “Humour is also a strategy to decompose meaning because with a joke you can transform one solid thing into something very flexible,” he says. Sometimes it arises in his work by accident and he is compelled to see the funny side, like the time he was sanding the wooden floor in his studio and left the switch on. The sander went berserk on his floor, reminding him of Donald Duck, so he made a wooden duck’s head for the machine; a comical dig at hi-tech gadgets.

“I used to be more calm and watch my brother opening and destroying all the kitchen machines while my mother was screaming. And after years I did it professionally”

Ortega was born in 1967, not far from where he works now. His father was an actor in political theatre and his mother was a teacher. He attended an experimental school run by leftwing intellectuals, where the children learned skills like embroidery, carpentry and ceramics alongside traditional subjects in an atmosphere of total freedom and creative play, which undoubtedly fed into his approach to materials. Later, he and his brother would accompany their father to communist party festivals for concerts, painting and dancing. Ortega began working for the leftist newspaper La Jornada as a political cartoonist. “For my father it was more understandable for me to make political art than abstract art, which was very bourgeois,” he notes. “It took eight years for me to play with abstraction, or just not figurative things.”

Módulo de Construcción con Tortillas, 1998

But ultimately Ortega wanted to make art that transcended politics. He visited the artist Gabriel Orozco, son of another, more radical communist, and asked to be mentored. Their weekly lessons turned into legendary “Friday workshops”, which took place between 1987 and 1992 and included Abraham Cruzvillegas

, Jerónimo López Ramírez, aka Dr Lakra, and Gabriel Kuri—all now big names on the Mexican art scene. Influenced by the conceptual ideas of Marcel Duchamp, they found the conservative approach taught in Mexican universities repressive. “You need to work a lot to find a piece of marble or to make an oil painting. And maybe an oil painting was not the precise material to describe what we were thinking or feeling or dreaming or wishing,” Ortega explains. “We started to play more with our own context, the objects around us—kitchen supplies, food, manipulating these materials. It became more personal, more subjective, individual, these actions into our community, our houses, our way of living.”

Theirs was a generation characterized by resourcefulness. When museums weren’t showing their work they exhibited in an empty house lent by an acquaintance; when they had no gallery to represent them, they got their friends Jose Kuri and Monica Manzutto to form one. Frustrated by the lack of available Spanish translations of artists’ texts, Ortega started his own publishing project Alias, which now has some twenty titles. The first book, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, evolved in a typically Ortega-esque, deconstructive manner. Given the original by Orozco, he asked friends each to translate a page, resulting in a mishmash of Mexicanisms and in-jokes in different typographies and voices, which would certainly have appealed to Duchamp. Ortega sees the project as inseparable from his work: “It’s also a sculpture, an object which has meaning, which is political, influential, which transforms our space directly to ideas. It’s more like a virus which is moving in different geographies and expanding.”

As we watch the engineer swaying on a test stack of bricks in the warehouse, Ortega remarks that a journalist recently grilled him about why he had shifted from making industrial objects to organic matter. It strikes me that his works have always combined ephemerality and permanence, revelling in the tension of opposites, frailty versus mass. Ortega agrees, but such is the fame of his generation of artists these days that it’s like a rock star meeting fans who know all their lyrics. “Yes, they think ‘Your first record is better,’” he says with a grin.