War memorials, wrestling matches, or socialist public monuments? In her solo exhibition at Lismore Castle Arts, the German sculptor puts the spotlight on the 1930s dance marathon phenomenon.

In the closing scene of Sydney Pollack’s Depression-era drama, weeks of relentless dancing and mounting despair culminate in a moment of quiet acquiescence for Gloria (Jane Fonda) and Robert (Michael Sarrazin). Confronted with the futility of their struggle – clocking upwards of a thousand hours of one-step and waltzing at the Santa Monica dance marathon – they walk away from the prize money and onto the pier. With the sea thrashing against the pilings, Gloria draws a pistol from her purse. Unable to end her own life, she begs Robert to assist her, and, after a moment of hesitation, he complies. When questioned by the police about his actions, Robert utters the haunting final words: “They shoot horses, don’t they?”

This harrowing finale is brought to mind in German sculptor Nicole Wermers’ most recent work, a solo exhibition hosted by Lismore Castle Arts which continues until May 25th. “I’ve wanted to create a piece of artwork centred on the subjects of the marathon dance competitions for something like twelve years,” Wermers tells me from her home in London.

The short-lived craze that swept through America in the 1920s and 30s was a rather grim spectator sport. Throngs of paying customers watched contestants push their bodies to the brink – dancing for days, weeks, even months on end. Exhausted and semi-conscious, they clung to partners, lured by prize money and whatever loose change the audience might throw onto the floor. Medical staff stood by – not just for safety, but for show, heightening the theatrics of the Darwinian drama.

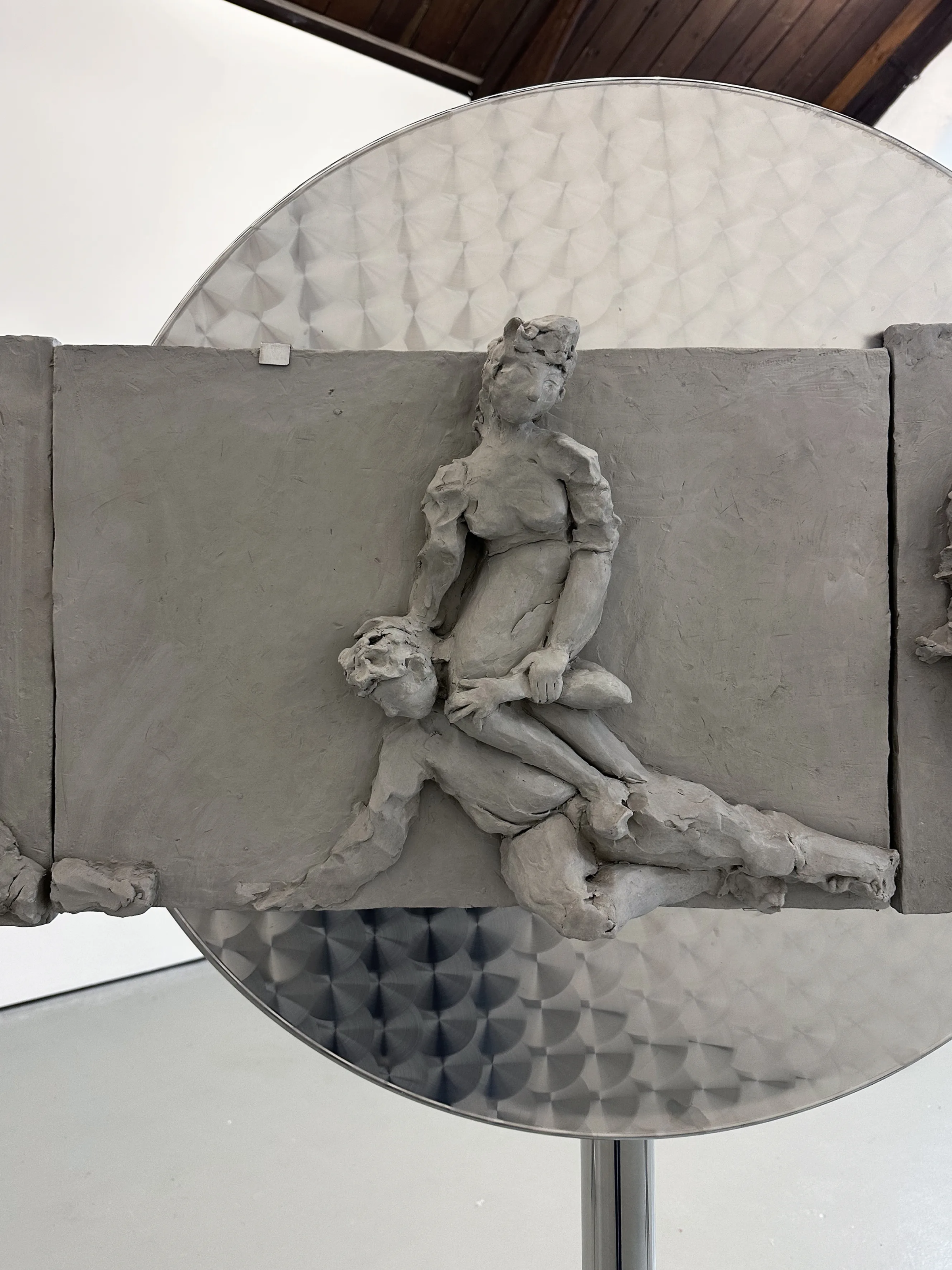

Marathon Dance Relief (2025) oscillates between the violence and tenderness of its titular phenomenon. Set within St. Carthage Hall – the hallowed project space at Lismore Castle – the installation comprises eleven relief slabs made by Wermers, mounted on a chorus line of upward-folded metal tables. Succeeding her solo show, Day Care, at The Common Guild in Glasgow, the artist deepens her exploration of invisible labour and body economics by sculpting forms that convey both the delicate and brutal aspects of endurance. “I don’t think the notion of entertainment as labour had happened before on this kind of scale,” says Wermers. “Dancing had always been a form of recreation but in these competitions, it was distorted to a point of cruel exploitation.”

For her veritable storyboard of exhaustion, Wermers could not have sought a medium more fitting, nor more evocative, than that of relief. The concept is central, carrying a dual meaning – both in the fleeting 15-minute rest periods granted to marathon participants and in the form’s rich artistic tradition. “Relief sculpture is deeply embedded in art history – from obelisks and friezes to public edifices and church interiors,” Wermers reflects. “Historically, they have depicted scenes of physical labour and craftsmanship, often celebrating the processes of construction. In ancient Egypt, for example, reliefs portrayed the efforts behind building the pyramids, making the invisible, visible. Somewhere along the way, the attitude to labour changed. Through its dematerialisation, I’ve become more interested in looking into the past.”

A historical sculpture technique like relief perfectly embodies what Wermers calls “the strange in-between-ness” we inhabit today: “the space between the flat, screen-based two-dimensional and the fully realised world.” Honouring this tradition, the artist’s sketchy relief slabs – hand-built in clay – capture the relentless motion of these anonymous dancers (often referred to by number rather than name), as well as the physicality of Wermers’ own artistic efforts. Formally too, Wermers sculptural eye finds resonance in the partner dynamics of the widely-photographed participants. “There tends to be one figure in the couple that hangs off the other, which reminded me of the counterpoised legs in classical sculpture,” she notes. “My figures embrace, collapse, and support each other in a similar way – fighting gravity, exhaustion, and even one another.”

Arranged in the style of an architectural frieze and mounted onto bistro tables, Marathon Dance Relief engages with the boundaries of private and public realms and the ways in which design manufactures social structures. “I’m very much interested in how hierarchies manifest in surfaces, materials, and shapes,” Wermers reflects. “These bistro tables are often found in spaces where the private and the public are constantly negotiated.” The tables, Wermers implies, are perhaps amongst the most democratic of designs, setting the scene for a life lived as much as it is performed.

The gallery space – a former Victorian church hall complete with its Christian spatial hierarchy of symmetrical axes and 90-degree angles built around the cross – adds another layer of meaning to the installation it accommodates. Wermers deliberately chooses to position the chorus line on the diagonal, disrupting the room’s formal symmetry and elevating the dancers to a position of public display. Not unlike her Reclining Female maintenance workers, supine on the altar of their housekeeping arsenal, the chorus line’s assertive presence makes a spectacle out of those who are usually confined to life’s margins.

In Dance Marathons: Performing American Culture of the 1920s and 1930s (1994), Carol Martin’s penetrating analysis of the peculiar phenomenon, she observes that dance marathons “presented life lived as theatre” whereby “spectators are perpetually suspended between belief and disbelief.” Crowds came for entertainment at the expense of the performers’ physical and mental health, while those who organised and observed these spectacles still occupied spaces with enough privilege to dance for pleasure. “It was a position Bertolt Brecht would have appreciated,” she continues. “The enjoyment of an aesthetic phenomenon only partly masked as a real-life event.”

Still, the perverse appeal of endurance spectacles lives on. “The marathons were really a precursor to reality TV, specifically shows like Love Island and Big Brother,” Wermers tells me. “They grip the public’s imagination in much the same way, rooted in the idea of taking pleasure in others’ discomfort.” Both the dance competitions and their modern counterpart thrive on a voyeuristic fascination with desperation and human vulnerability.

As the UK appears to flounder in every corner – from raging culture wars, to disintegrating social infrastructure and abhorrent foreign policy – is it any wonder that we are drawn to the cheap thrills of televised psychological warfare, happy to retreat to the spectator seats at a safe distance from the unfolding chaos? As the rogue emcee Rocky solemnly proclaims in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969) perhaps people “just want to see a little misery out there so they can feel a little better.”

In more ways than one, the dance marathons of interwar America that Wermers observes in her artwork serve as a historical parallel to contemporary gig economies and the increasing precariousness of labour in the UK. In January this year, the government issued formal warnings to gig economy companies over the misclassification of workers as self-employed, a practice that often strips individuals of essential employment rights such as sick pay or holiday entitlement. Just as destitute and working-class dancers pushed their bodies to the limit for the possibility of minimal financial gain, today’s workers – whether in low-wage jobs, creative industries, or digital labour markets – must navigate a system that demands constant effort with little security or reward in return.

In 1923, as the craze for these oft-named “corn and callus carnivals” reached Washington, Mina Van Winkle of the Washington DC police warned The New York Times, “a dance epidemic always precedes national disaster, as clouds precede a storm.” Werners’ Marathon Dance Relief then feels especially prescient; with recession fears mounting after the government slashed this year’s growth forecast, her astute and unsettling installation reminds us of the relentless cycle of economic struggle. The grim underbelly of labour and exhaustion, its inevitable escort, lay bare a system where endurance is the performance – and collapse waits just beyond the velvet curtains.

Written by Millen Brown-Ewens