When in an art gallery, I find it unusual to be asked if I want to go somewhere more private to have sex or just stay where I am and do it in public. I paused for a few moments at the question, unsure how to reply before deciding that, hell, why not, let’s just do it in front of everybody. I pressed my hand down on the button, and it began.

I was in the Hot Stuff Hotel. Well, I wasn’t. I was in the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva, but the playable version of myself was in the weird, glitchy Hot Stuff Hotel. The button I affirmatively slammed had been built by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, and both the Hotel and unexpected question I found myself were conjured by her imagination. Brathwaite-Shirley is an artist who builds video games and then situates them into gallery spaces as an act of disrupting what may be expected from nice, polite spaces of mannered exhibition. The games, it seems, can also disrupt nice, polite, mannered people.

“It’s very interesting when you have someone that’s from a richer ilk approach this work, you see how uncomfortable they get with the fact that they just can’t suck it in,” the artist tells me. “They have to put something of themselves out, and my main aim is to do that, to literally say ‘I don’t care about your nice experience, none of this is nice, here you go, this is horrible!’” Her audiences can be confronted with some truly horrible experiences and expected to make decisions which make my public sex dilemma tame by comparison.

Not long after leaving Hot Stuff Hotel in the artist’s choose-your-own-adventure style experience, NO SPACE FOR REDEMPTION? (2023), I faced a darker choice. I was walking home alone along a dark street as footsteps behind me grew closer and louder. After a series of choices as to whether I should try to catch a glimpse to see if I’m being followed, to turn and face them, or to speed up, my character reached for a 10-inch machete they had concealed for just this situation. Then, I was given options:

- ATTACK WITHOUT WARNING: SLASH SLASH SLASH

- WARN THEM: NO SLASH NOT UNTIL THEY MAKE ME

Brathwaite-Shirley is black and trans, two characteristics that have always been front and centre to work, which deliberately puts the gallery viewer – gallery gamer, perhaps a better term – into difficult situations. “I feel like that you need to fucking make the art space into a space that actually challenges the audience,” she tells me, “because the audience has been going there, able to lie back and not think about the insane choices that they’ve made in life to get us to this point.”

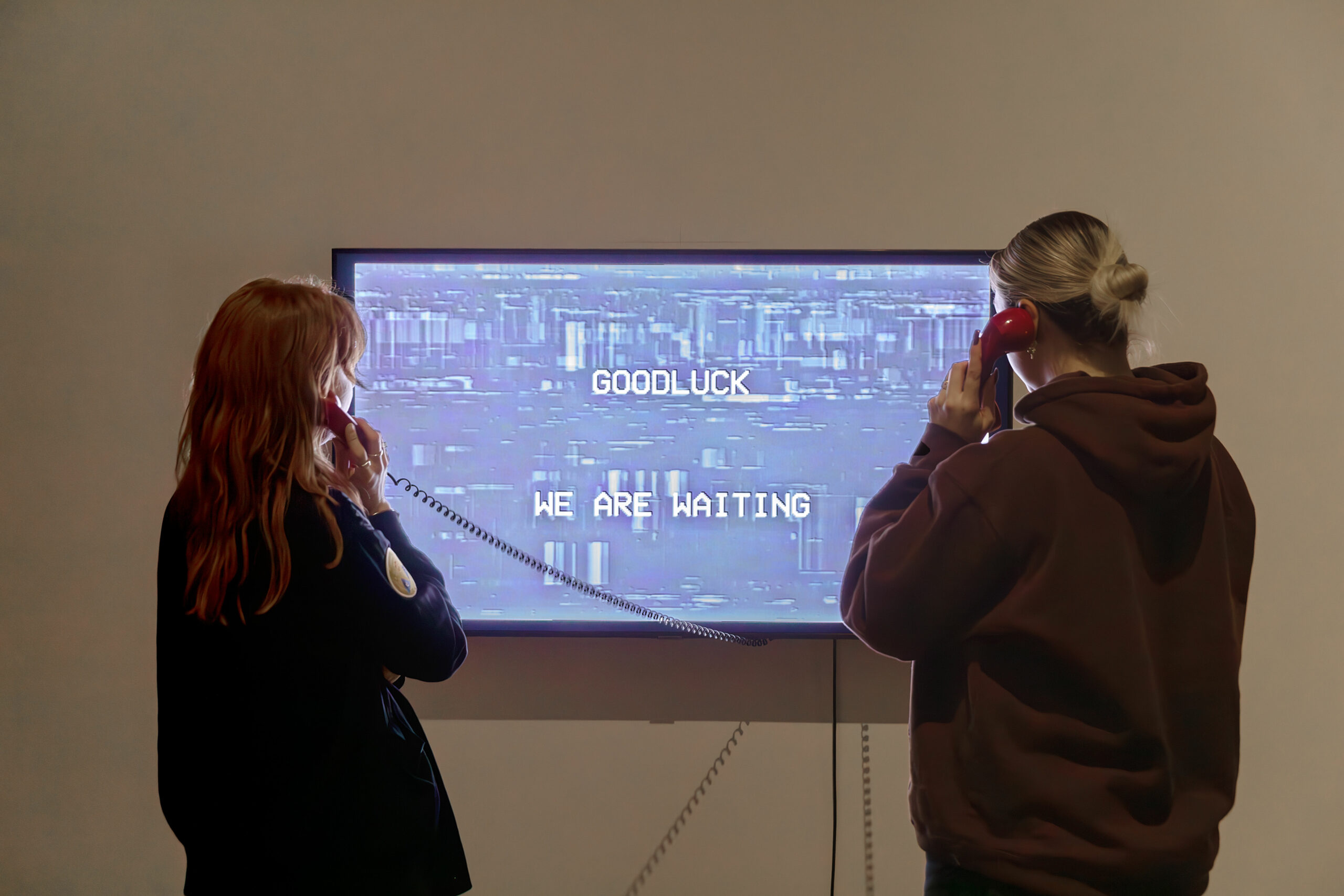

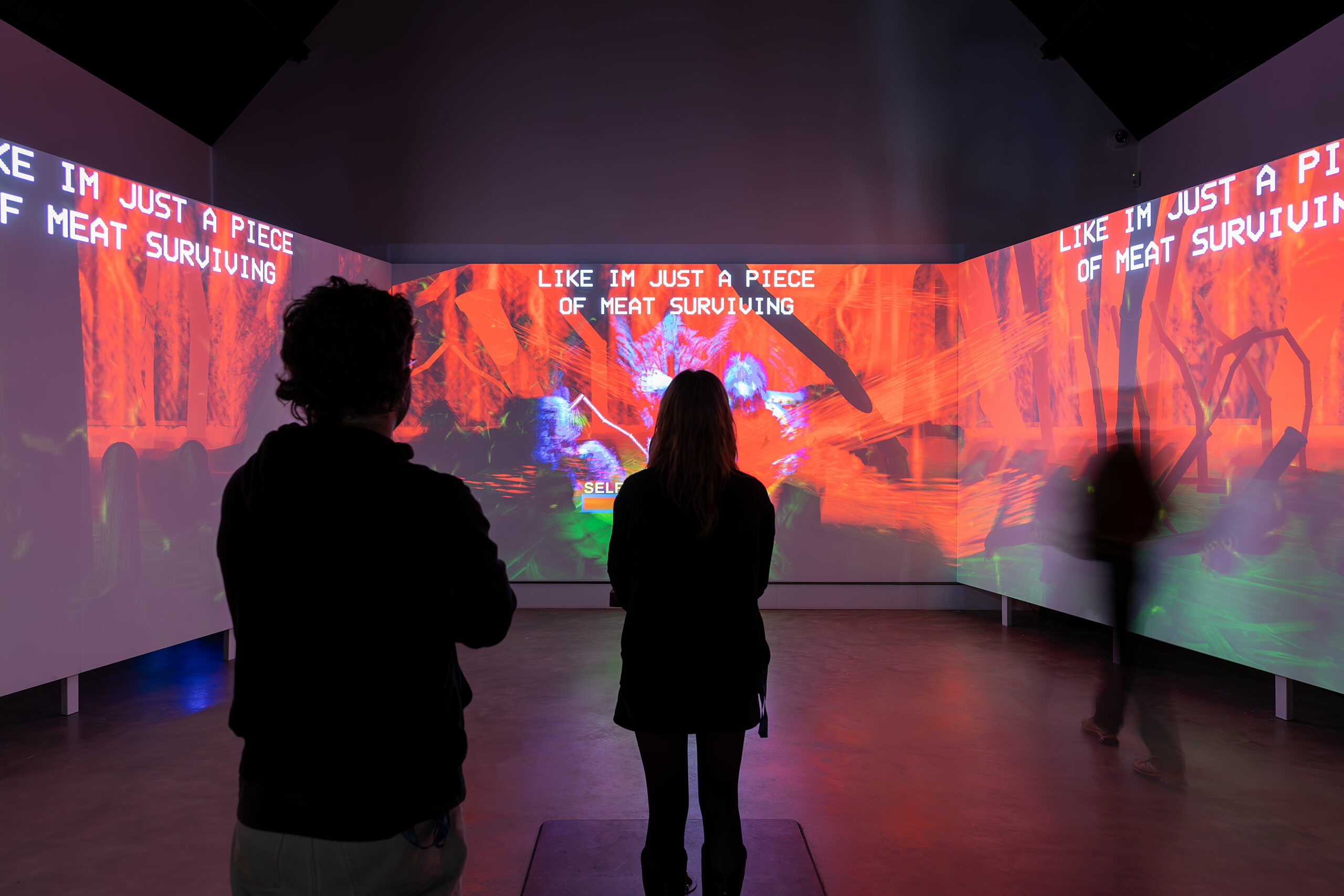

As the narrative unfolded, I sat in the centre of a square room as visuals and text were projected onto three walls around me; though the experience is not as calming as being surrounded by a room of Rothko’s, this was certainly no invitation to lie back and not think. The work is part of the Centre d’Art Contemporain’s Biennale de L’image en Mouvement – an eclectic mix of fifteen artist’s moving image work as Vanessa Murrell reported on for Elephant, and which included American Artist’s political provocation Yannis Window (2024) – and a narrative derived in part from the artist’s personal experiences. “A lot of it is basically a diary; most are actual encounters I had,” the artist tells me of the anxiety-inducing plot points,” they are all anecdotal problems I have that I don’t know how to deal with, five nightmare scenarios.”

The works are like scribbles from memory, texts that are quickly written down replete with typos and snagging syntax, carried by graphics and sound equally as frantic and scratchy within a punk aesthetic. “They’re made very quickly,” she says, “it’s all sketches, feelings thrown into one, compounded together like a collage that make this glitchy, weird game.” The typos are not intentional but are deliberately left in. If the finished pieces were polished and edited, with prose turned to fluent, florid language, polished graphics, and a cinematic soundtrack, the urgency would entirely be lost. The artist tells me that once a previous experiment with clean sound production simply didn’t work: “The way the story was told didn’t match this amazing, perfect sound – it needed mess, some sort of, I don’t know, smearing!”

The smearing breaks any photo-realism and allows the viewer into a space of semi-abstraction. “If we were to talk about a different medium for a second, they’re more like quick expressive paintings that try and hold emotions in the brushstrokes,” then, switching mediums between fine art and gaming, adds “rather than Death Stranding, which is meticulously detailed and imbued with exact notions of Hollywood.”

In the games-realm, polished and sublime triple- and quadruple-A games such as Death Stranding, Red Dead Redemption, or Horizon Zero Dawn are not the totality of the sector, and Brathwaite-Shirley’s games could be considered more alongside a range of political and agitprop provocations published independently. Games such as Papers Please, an immigration officer simulator, Not Tonight, where the player cosplays a post-Brexit bouncer trying to avoid deportation, or Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator for LGBTQ parent romance. Such games can invoke confrontational politics into a play situation more than their triple-A counterparts. But, the artist says, there is still “a subset of gamers that are like, ‘we don’t want politics in our games’.” With perhaps half a mind to ongoing discussions of suggested Arts Council England censorship and the removal of pro-Palestinian political statements across Germany, adds that “and now it’s in museums, and it’s in museums codes.”

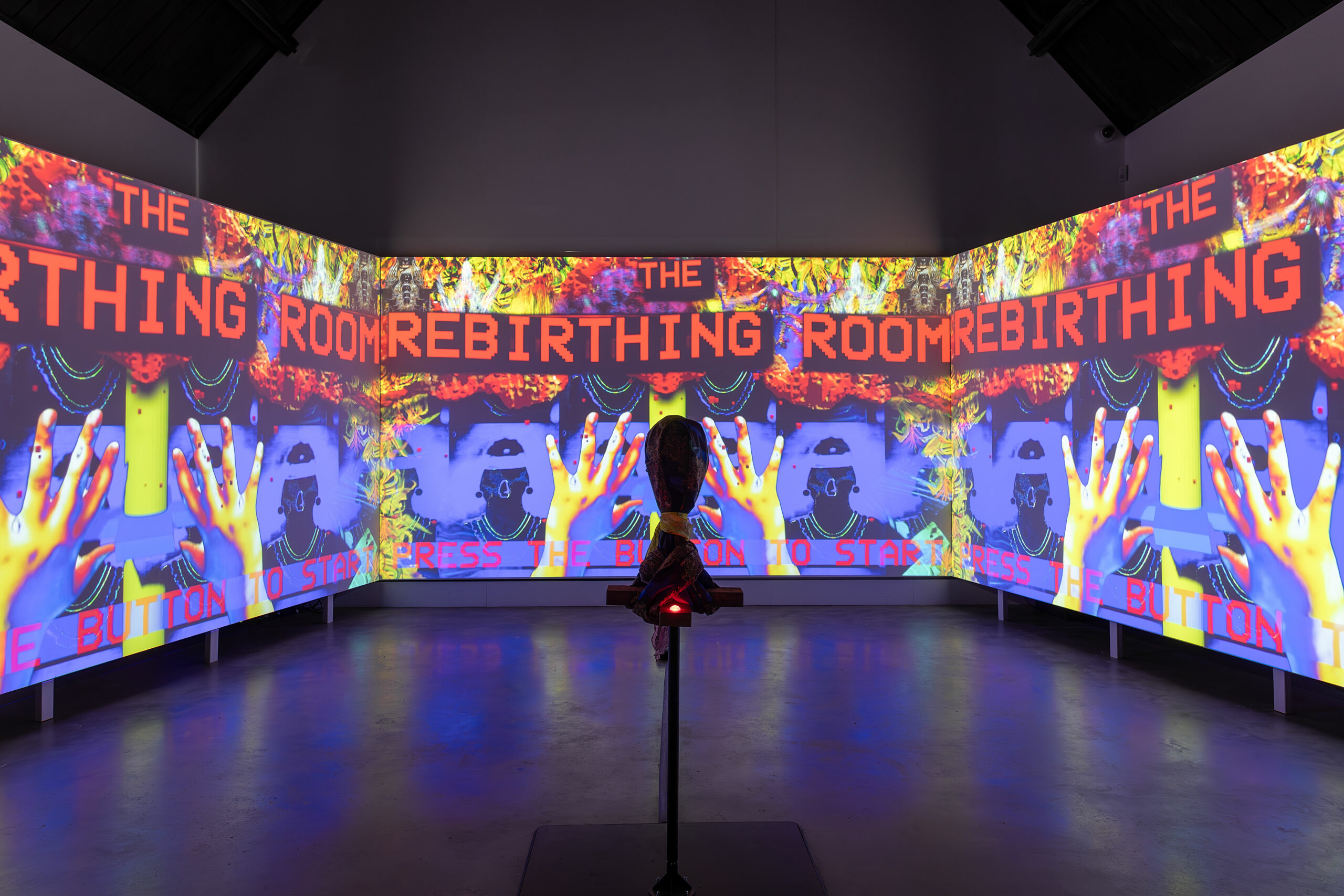

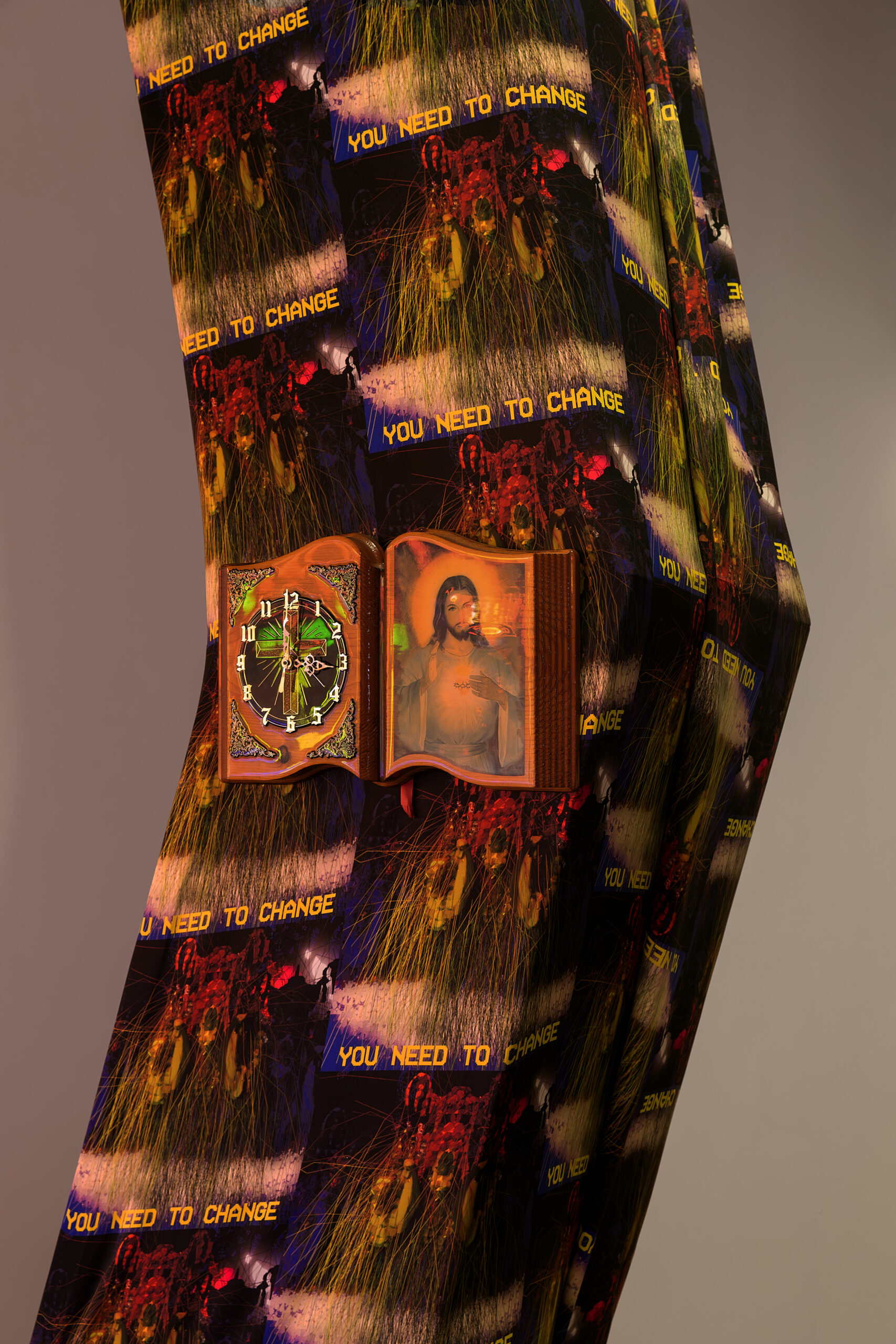

For Brathwaite-Shirley, it’s been a busy start to year that will only get more hectic. Not only did she have to finish the game for the Biennale de L’image en Mouvement – which required last-minute coding tweaks – but also had to put together a solo exhibition for London’s Studio Voltaire, one which is equally as confrontational. In THE REBIRTHING ROOM, a single visitor becomes the protagonist, holding the anchor, a controller built into a cross at the centre of the gallery. Across three screens a series of reveal themselves from shadows and overgrowth, then threateningly head towards the gallery-gamer who must fend them off in an increasingly anxious shoot ’em up. The demons all represent issues faced not only by Brathwaite-Shirley but most of us in the modern world: low self-esteem, fear of failure, addiction.

It marks a slight shift for the artist who has largely dealt with personal experiences focused around their Black Trans self, opening up into an area of more general and more widely shared issues of identity and self. “At a certain point, I was like, deifying Black-Transness as an experience and identity,” the artist says, reflecting on past works, “when a lot of the encounters I was having were more universal than I expected.” The Studio Voltaire project, an outcome of a 12-month residency supported by Meta Open Arts, is no less confrontational than previous projects, but instead of forcing the visitor into a confrontation over Black Trans allyship and understanding, it forces inner reflection and exploration of self.

“I feel like right now I’m trying to connect with people, that the work is trying to connect with you and it’s just trying to say ‘I just want to talk to you’, whoever you is,” the artist explains, “I want to talk directly and connect to you in some way.” I didn’t beat any of my demon accosters and asked Brathwaite-Shirley if the monsters were even beatable at all, or if in fact THE REBIRTHING ROOM is training us to understand we will have to live with our demons. “I’ve seen one person complete one level, so yes,” she replies – but it seems most of us will need to get used to the constant demon attacks.

“A show I’m planning later this year should be impossible to complete alone,” the artist tells me of a future project which sounds equally as tough, “and it will require immense amounts of collaboration, which I 100% believe will never happen.” There seems to be no let-up in the confrontation, force, urgency, and energy in Brathwaite-Shirley’s many upcoming projects. These include a major installation at Halle am Berghain in Brathwaite-Shirley’s home city, Berlin, a commission from LAS Art Foundation for whom Lawrence Lek recently created a world of empathic AI cars. In the Halle, one Studio Voltaire’s demons will return: “You’re walking down the stairs into a basement and there’s a demon down there, it’s like a scene from a horror movie, that’s what the audience should feel the entire time.”

Also in the pipeline are a series of NFTs for MOMA. “I think NFT’s suck,” the artist tells me, “but that’s why I’ve made Cancel Yourself ones – you’ll get an NFT saying you’ve been cancelled for racism, or something like that.” Then there’s a project for Barcelona’s Joan Miró Foundation in which “the show is all burnt bodies, that’s all it is, the show is horrible, and my aim is to get people to leave the gallery.” There is also, she tells me, “possibly a massive show next year that’s crazy,” nervously adding, “but I’m not gonna say anything about it,” followed by an infectious laugh.

That laugh is key to the artist. There is undoubtedly darkness, despair, and depths in Brathwaite-Shirley’s glitchy, haunting worlds, and they are not only confrontational but are deliberately abrasive, angry, threatening, and scary. Her games are unashamedly political, forcing the visitor into answering difficult questions, whether internally or with publicly visible narrative decisions. But there is a humour – albeit dark – throughout the situations, text, and aesthetic, which along with politics is a key part of the glue which keeps the fragile and existential digital collages together.

“The art world is famously fantastic at looking at a piece of art with politics, then taking away the politics and saying, ‘just look at the image!’,” the artist tells me, adding that “there’s a reason commercial galleries sell paintings of handprints, there’s a reason gay artists don’t sell very much, there’s a reason most work with political meaning is rewritten about and sells twenty years later.” Brathwaite-Shirley has created a singular type of artwork that simply can’t work in this way, where the image is the political component, where if the politics were to be removed, then nothing would remain.

Brathwaite-Shirley is aware that her approach doesn’t always sit comfortably into how many galleries and institutions work. “I often say that I’m not trying to make art, I’m trying to change art,” they say, and an encounter with one of her works is quite unlike most gallery experiences. The visitor who is not forced to flee will unlikely emerge refreshed and revived: “I would love the idea that you go to a gallery and it feels like a workout or is a mental excursion, or is like a gym routine,” the artist says, before pausing, “… or like therapy.”

Written by Will Jennings

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: THE REBIRTHING ROOM at Studio Voltaire

31 January – 28 April 2024

find out more