Tal R speaks calm, idiosyncratic and unaccented Danish amidst the organized chaos of his hangarlike studio in central Copenhagen. But he maintains and even underlines the privilege of an outsider. He was born Tal Rosenzweig in Tel Aviv to a Danish mother and a Czechoslovakian Jewish father in 1967. The family moved to Copenhagen when he was one. Now, Tal R is probably Denmark’s most recognizable painter (though he works in sculpture, collage and other forms besides). The Danish capital has provided him with countless subjects. But only as an intruder can he truly break the culture of a place open, he says.

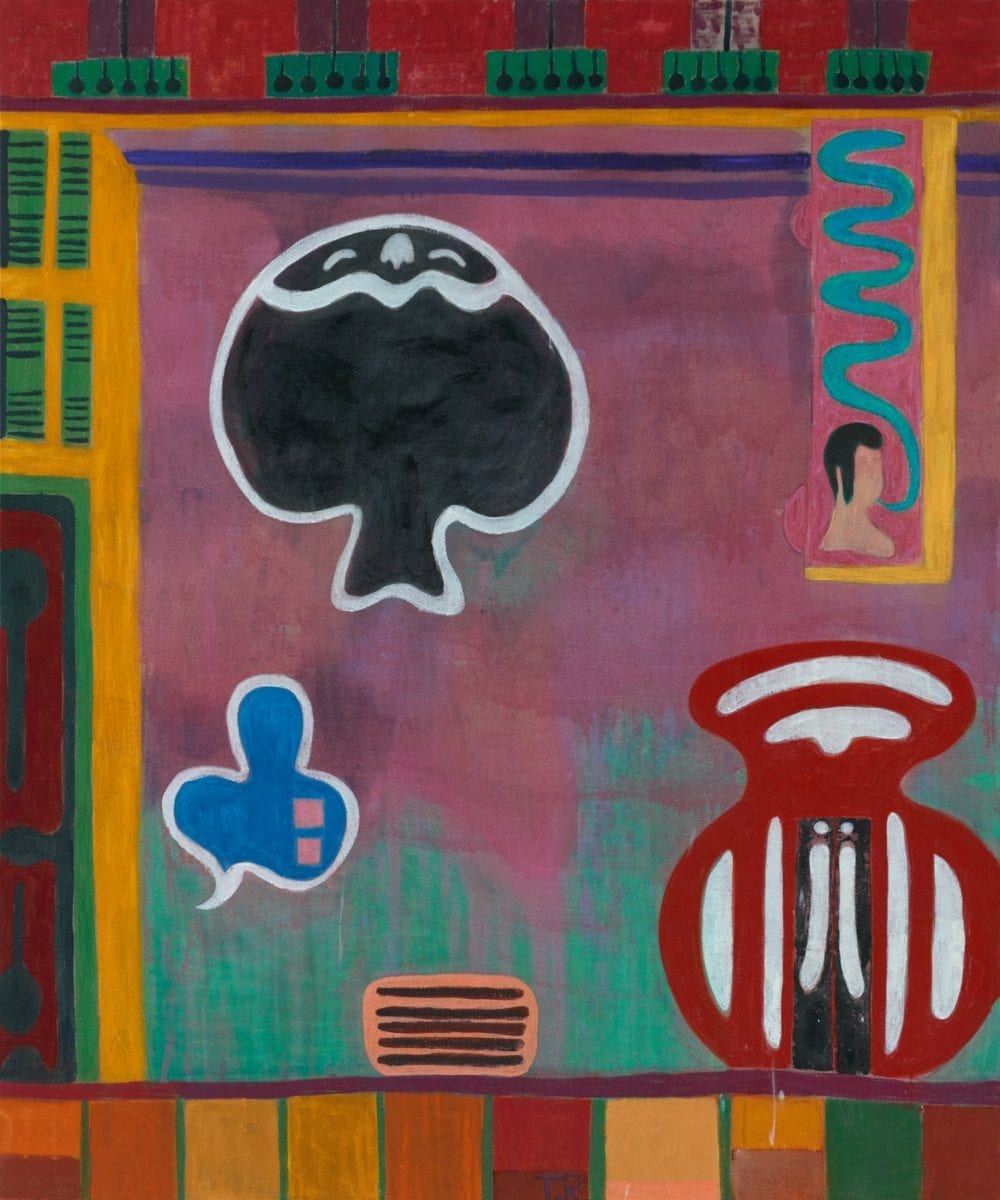

Consistent identifying features of his work, in painting at least, include a striking vibrancy of colour and application that combine knowing sophistication with childlike frankness. He is increasingly allowing heroes and forebears—Henri Matisse, William Copley and Philip Guston among them—to peek through his own canvases. But Tal R’s distinctive use of colour and his glimpses of the fantastical—often in ordinary street scenes or straight architectural images—are all his own. So is the sheer brawn of his brushstrokes. He first exhibited at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, north of Copenhagen, in 2007. This summer the museum presented a major retrospective together with a new set of nine uniform-sized canvases, each bearing the image of a railcar. Later this year, an extension of his series depicting the façades of sex shops from around the world, the seeds of which were first sown in the Cheim & Read show Keyhole, will appear at Victoria Miro in London under the new title Sexshops. In both these works and the huge railcar paintings, he uses a distemper technique, mixing pigment with rabbit-skin glue to “make the canvases vibrate”. The result is a surface intensity that some have likened to Rothko’s.

He has used the method since the late noughties (though he has continued to use oils as well). But the luminosity that the substance induces is also intrinsically linked to the large, fat areas of rooted colour that have been one of his hallmarks for far longer. Thrown into this are elements of hand-drawing and areas of sudden detail that can appear to have wandered in from different works. Sensuality was always a central element of his pictures. In Sexshops, it is forced out by its own obviousness.

Some critics have observed a solidification of his work recently: a move from something jocular and seemingly disposable to something more solid and resonant, just as his use of undiluted colour has gained confidence while checking its own privilege at the same time. “I think something has changed,” he admits. “I’m going somewhere else now.” But some established elements of Tal R’s practice, you feel, will always remain. His hyperimagination in the face of everyday objects is one of them. Some sense of the enigmatic secrets behind those objects is another. A third is the honesty and vitality—both complex and innocent—with which he talks about his work.

The title of your Louisiana show is Academy of Tal R. Is that a joke?

That was [Anders Kold] the curator’s idea, but I accepted it. I was not so sure about “Academy of Me”. But “academy” is a nice word because although my approach is not very academic, I taught for ten years in one of the biggest art academies in Europe [Kunstakademie Düsseldorf] and I was always interested in how to communicate ideas. In reality I worked in many different directions at the same time, directions that in a normal intellectual way work against each other—minimalism on the one hand, very clear narratives on the other. I suppose I was always fishing between the two approaches. I would do a painting of the façade of a sex shop, but then I would notice certain patterns emerging that would become abstract forms. I would wear them down until they cracked and changed.

- Chez La Souris, 2017

- Blue Moon, 2015

You have said that you found academic study restricting, nullifying.

I found it frustrating to a point. If you grow up making cinnamon rolls with your mum every Sunday, and it’s the best time of your childhood, you’re asking for trouble if you then decide to become a baker. Drawing was freedom for me in my childhood. I would draw weapons, war, everything terrible. And I would enjoy it. So to enter art school was a disaster and it took me almost ten years to get back to the same place—where to make art was to work on what was important. It’s a Bermuda Triangle, because you then have art history. When you first see Philip Guston, it kills you—it’s like a hand grenade in your shoe. Later it becomes a stone in your shoe, and that makes you walk a little more carefully, which is when art history starts working for you. When you’ve got fatness and you want to have narrative, you can look at Matisse and become cleverer. Then there is the most important element: your own stupid necessity, your own dirty laundry. You have to find a method, a way of articulating it. For me that might be a train, or a moon reflecting in water. What I found most complicated when teaching was getting the students to connect their dirty laundry to the outside world. That connection is quite hard to make and ultimately you have to do it on your own.

“In a way the sex shop paintings are dealing more with pattern painting, with Rothko, than with anything sordid”

But you’re trying to lock something down, are you?

I don’t think you’re really “assessing” as an artist. If you are dilettante, you are going to have a lot of questions about your subject matter: Why this, why that? Actually you don’t know, and that’s why you make art. You don’t make art to get psychological answers back. You simply unfold the mystery of your own interest. You say, “I look at this and I am stunned by it. It rings a bell.” You don’t care why the bell rings, you just know there is the possibility of unpacking something. So you’re driven by stuff that you are not really in control of.

Is that why most of your subjects are everyday, even banal objects—train carriages, for example?

You look for objects that mirror something that you don’t know anymore; that’s where the possibility for you to express yourself lies. There are all sorts of questions about trains: why isn’t the train obsolete when it can only run on tracks but a car can drive anywhere? I like that stupidity, and the fact that train tracks form a sort of skeleton over Europe. Right now Europe is changing beyond our control. You might say, in the end, that what connects it is just the trains. Ultimately if you ask me what the train means, I can make up stuff, I can try to think about it, but you have to understand that I’m not really sure.

Let’s talk about sex shops.

There is something that connects paintings and sex shops. A painting is a flat surface that promises you something, but it’s actually just a piece of canvas. A sex shop always promises you something but you know you’re going to be disappointed. I did a painting of a sex shop in Copenhagen, and I thought it could be nice to do a whole body of work only around these places, because they have this cheap attraction. It’s like a pop song. But when you look at my sex shops they’re not obscene, they’re just weird pattern paintings. I think in a way they’re dealing more with pattern painting, with Rothko, than with anything sordid.

Technically, they are bang in your traditional style: blocks of colour.

And they are two-dimensional. Every other shop is three-dimensional, because in every other shop you have to look what’s inside. With a sex shop the façade is almost always flat, because there has to be an expectation or a fantasy of what happens inside. Plus, it’s private. So there’s this weird thing that a sex shop is like a police station—you can’t look inside it. Like the church or the synagogue, they are promising something.

So there is still a narrative at work here, as in most of your recent previous works?

Around 2008, I understood that my painting was going in a certain direction: into very clear ornamental crosses, lines, ornaments. And then I decided I was not ready for this kind of ornamental “downhill”, so I started to do clearer narratives— narratives that I could explain over the phone: “man walking down the street”, “moon reflecting on water”, “girls in pharmacy”, things like that. So I thought, OK, I need a new technique for this, something slower. That’s where the distemper method came from, because you can’t play around with it like you can with oils. It just happens that eight years later I’m still here.

Has it solidified your work?

I certainly started as a painter by trying to do paintings that didn’t exist—that were consciously on the periphery of art history. I think a lot of the paintings I do now are in the “main room”, and that’s the biggest challenge you can take as an artist, to reach towards something that almost looks normal; to be next to all of your heroes and say, “No problem.” That takes something.

This feature originally appeared in issue 32

BUY ISSUE 32