Four years ago, I stood entranced in front of Wadsworth A Jarrell’s painting Revolutionary (Angela Davis) while visiting the Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power exhibition at Tate Modern. Hand-rendered lettering emanates from the image’s focal point, the determined, proclaiming mouth of Angela Davis. It’s the only inch of quiet space in a swirling vortex of words, aptly conveying the former Black Panther’s oratory power. Jarrell powerfully blurs the boundary of graphic design and fine art, and carefully, yet explosively, channels his defiance of discipline onto the canvas.

Revolutionary was painted in 1971, but it was in 1968 that Jarrell co-founded the Coalition of Black Revolutionary Artists (COBRA) with his partner Jae Jarrell and artists Barbara Jones-Hogu, Gerald Williams and Jeff Donaldson. Based on the south side of Chicago, the group were intent on exploring a Black aesthetic. They were partly inspired by a project from the previous year entitled the Wall of Respect.

“They were drawn to methods of mass production: the accessibility of the poster, in comparison to a painting, means that everyone could own one”

This 20-by-60-ft mural brought together Chicago creatives to brighten up a dilapidated bar on the corner of 43rd Street and Langley Avenue. Honouring African American heroes such as WEB Du Bois, Malcolm X and Nina Simone, the mural was a statement of pride in Black culture and an integral space in terms of organising Black artists and uniting them in an expression of coalition. The concept was dreamed up by the artist William Walker, designed by Laini (Sylvia) Abernathy and painted by 21 artists and photographers, many of whom were involved with the visual arts workshop of OBAC (Organization of Black American Culture).

So, when Jeff Donaldson requested that a group of artists, who had been weaving in and out of these different outfits for the last few years, meet in Wadsworth Jarrell’s studio in 1968, it was difficult to refuse. Jones-Hogu recalled that Donaldson wanted to discuss the premise that “Black visual art has innate and intrinsic creative components” and the group’s meetings analysed the recurring aesthetic themes in the artists’ work, characterised by bright colours, human figures, lettering and strong socio-political imagery. It was decided that functionalism would underpin their philosophy as a collective, and art would be used as a tool of communication.

Jae Jarrell, Urban Wall Suit, ca. 1969. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of R.M. Atwater, Anna Wolfrom Dove, Alice Fiebiger, Joseph Fiebiger, Belle Campbell Harriss, and Emma L. Hyde, by exchange, Designated Purchase Fund, Mary Smith Dorward Fund, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, and Carll H. de Silver Fund © the artist. Photo: Brooklyn Museum

They were also drawn to methods of mass production: the accessibility of the poster, in comparison to a painting, means that everyone could own one. The intention was to make art not for critics, but for the people, an intention amplified by the group’s philosophical emphasis on, in Jones-Hogu”s words, “identifying problems, and solutions to problems, which we as Black people experience”.

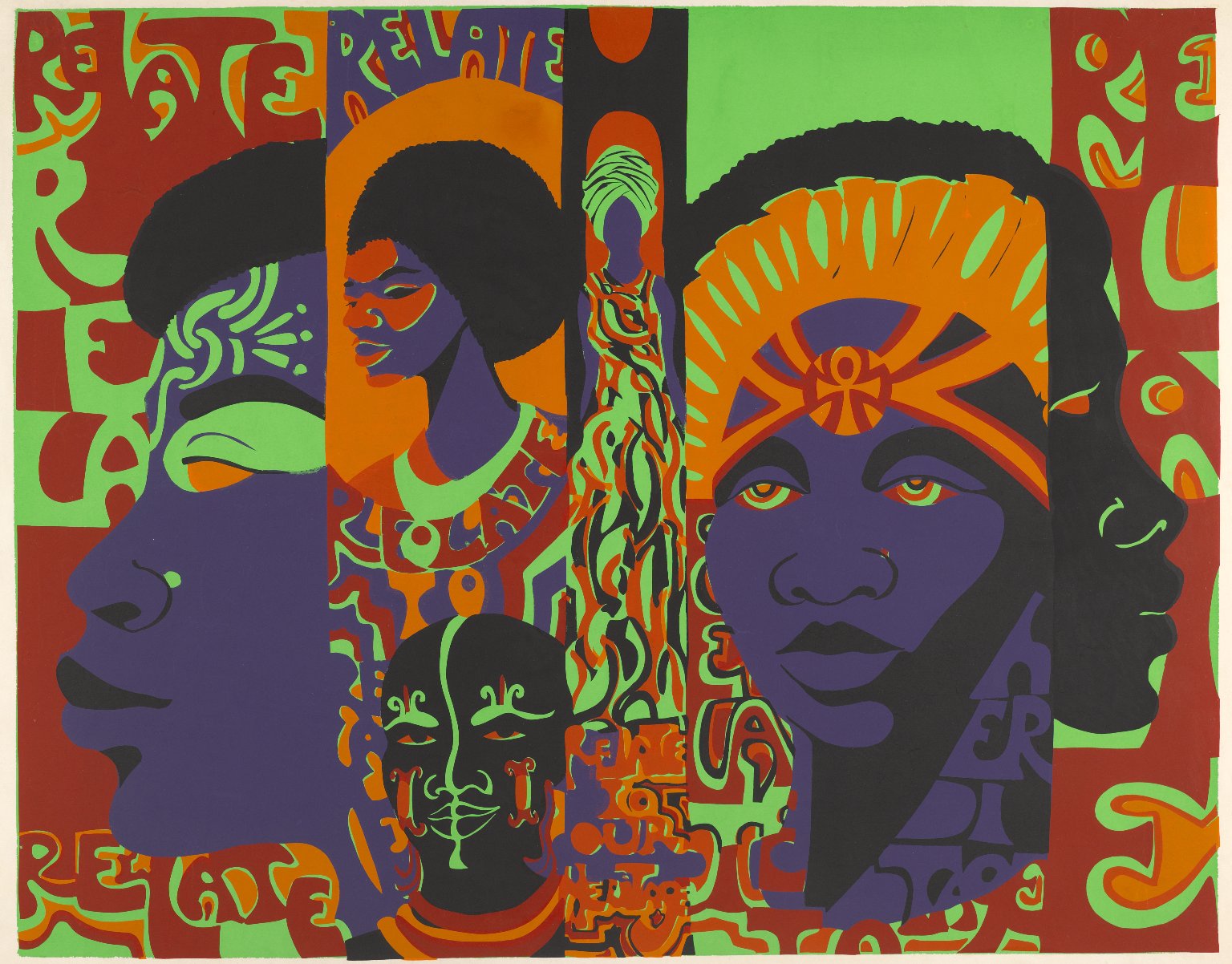

The evolution of the collective’s name from COBRA to AfriCOBRA in 1969 (with the initials eventually changing to mean African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) stemmed from wanting to acknowledge an international perspective. Drawn from African art forms as well as the styles of the artists, their aesthetic principles drew on ideas of syncopated, rhythmic repetition, aiming for a midpoint between abstraction and naturalism. Luminosity and bright colour were identified as imperative to a Black aesthetic, inspired by “the personal grooming of shoes, hair… [or] skin.” These values were documented in AfriCOBRA’s 1969 manifesto, Ten in Search of a Nation.

“Drawn from African art forms as well as the styles of the artists, their aesthetic principles drew on ideas of syncopated, rhythmic repetition”

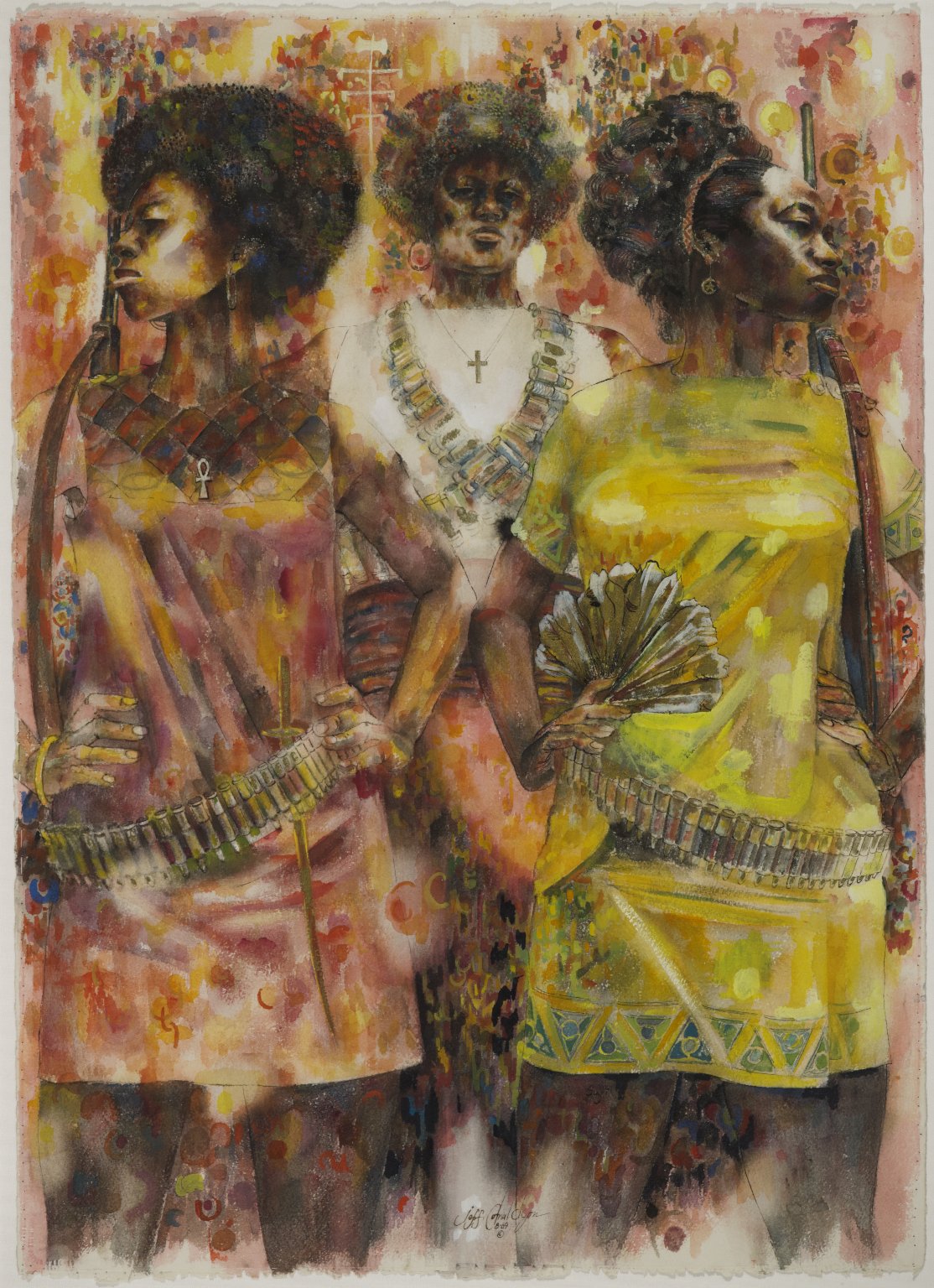

Two shows at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1970-71 showcased the group’s ideas. Nelson Steven’s Jihad Nation explored what it means to spiritually build a nation through vividly abstracted faces, while Jeff Donaldson’s Wives of Shango showcases three combat-ready sisters, sporting bullets and guns, in a delicately rendered, painterly homage.

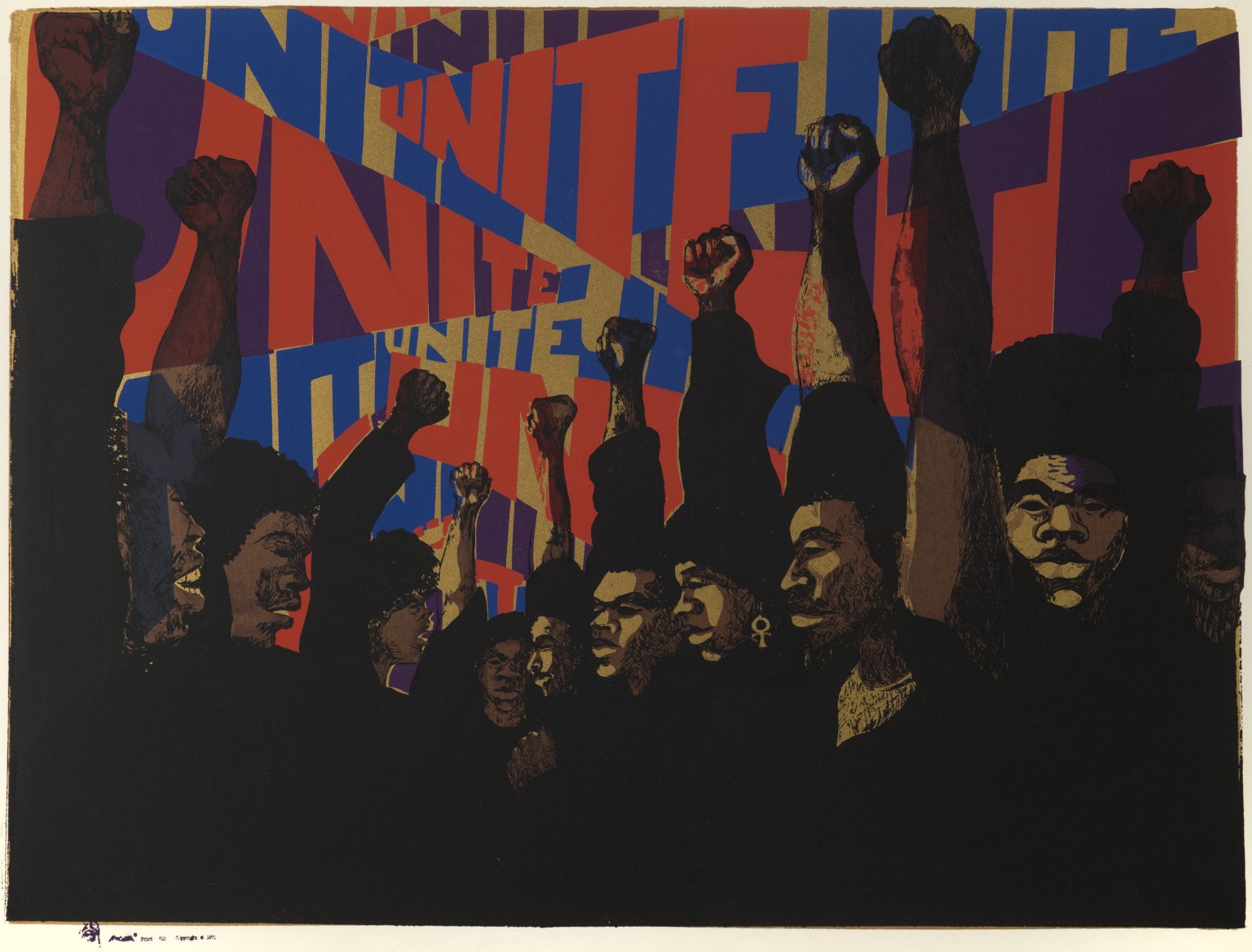

Jae Jarrell harnessed the power of paint and patchwork to replicate graffiti in her garment Urban Wall Suit. Carolyn Lawrence emphasised the importance of familial relations through explosive lettering set against warm hues in Uphold Your Men, Unify Your Families, while Jones-Hogu urged the community to Unite in an image that has come to characterise the Black Arts Movement.

A 2015 exhibition at the Harvey B Gantt Center looked back on the history of the collective by focusing on two strands: AfriCOBRA, which examines works from members who joined in 1968; and AfriCOBRA Now which highlights work from current members after the passing of Donaldson in 2004. Curator Michael D Harris explains the evolution of the collective’s aesthetic over the past 40 years as moving away from bright, Kool-aid colours into a more complicated colour palette, melding abstraction and furthering conceptual ways of working

Kevin Cole, one of the youngest members of the group, highlights the AfriCOBRA parallels between music and art. “What does colour sound like?” he asks. “It’s about the cacophony of sound. It may be rap, it may be jazz, it may be R&B or gospel, but it tells a positive story of African Americans which is not seen a lot, but they were doing it years ago.”

Perhaps the overarching message that we can take from AfriCOBRA today is not just one of positivity or autonomy, but also of the importance of collective resilience, in creating a movement that transcends the work of individual members to visualise a future of vibrance and joy.