A year ago, one month before the 57th Venice Biennale, Dirk Braeckman sat across from me on his balcony in Ghent, smoking a cigarette, pouring us glasses of afternoon champagne and effectively avoiding the subject of his upcoming solo exhibition at the Belgian Pavilion. “If I tell you what I want to do there, you’ll immediately form a picture of it, and come to the photographs with expectations.”

With weeks to go before the opening, he could still change his mind about what and how to exhibit. “I always work until the last minute. I want to have the freedom to change. Even during the show, I want to know that I can go further if I want to.” He stubs out a cigarette, to the soundtrack of church bells ringing on a Flemish Sunday.

“Planning is very technical. I’m not against planning or organizing,” he laughs a little. “Quite the opposite: I’m impressed that some people can do it. Fantastic! Wow! But it’s not for me. No.” Braeckman emphasizes impulse. His own, and also the impulse of those encountering his work. “People want stories—about how the photographs are made, the places I take pictures, about loneliness. But I don’t think any of that is important,” he says. “All you have to deal with is the picture. Just look at the picture.”

I guess it’s been a while since Braeckman has seen daylight. He calls his darkroom a sacred place, tells me he doesn’t allow anyone there, and makes a point of saying that it’s well-ventilated. I’m relieved hearing it, considering the chemicals and the hours and days he spends in there waiting for an idea to amount to more than that. Waiting is a ritual. It used to bother the artist, now he accepts that anxiously vacuuming the room in an effort to do something is part of doing something. “I need that kind of doubt. I need to feel frightened.” He gives the example of a painter in front of an unfinished canvas. As a young man, Braeckman wanted to be one. He initially studied photography as a way to aid that pursuit. Though he never put the photo camera down after picking it up, he says he “still thinks like a painter”.

“Sometimes I leave the darkroom without doing anything,” he says. “I need more time. Sometimes the work goes very fast. Sometimes in one print.”

“Do you ever start to worry if it doesn’t happen?” I wonder.

“I’m a worried person, yeah,” he tells me.

The works that end up at the Belgian Pavilion are large-scale—mostly new, though chronology is a problematic metric of Braeckman’s work. He leaves his negatives alone for at least a year—or five, or ten. He refuses to touch recent negatives. “I distance myself from the emotions of the moment I took the picture. It’s better that way.” One negative can lead to three or seven different photographs. With Braeckman, time is as irrelevant as geography. Someone once asked the artist if a photograph was taken in his kitchen in Belgium. The picture was actually taken in Senegal. “Either way, it doesn’t matter,” Braeckman says. “A photograph is not the truth.”

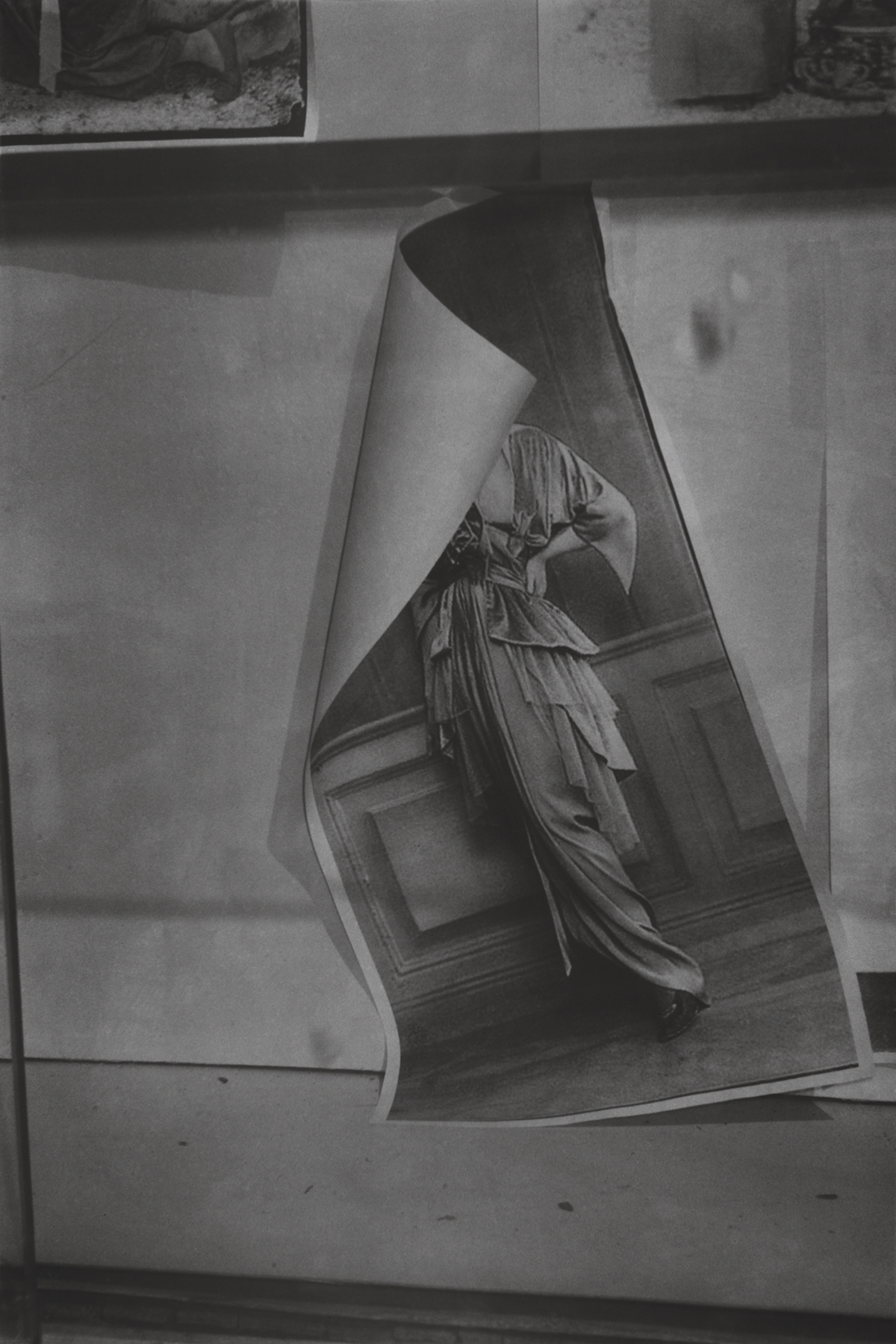

- Installation view at Bozar, 2018

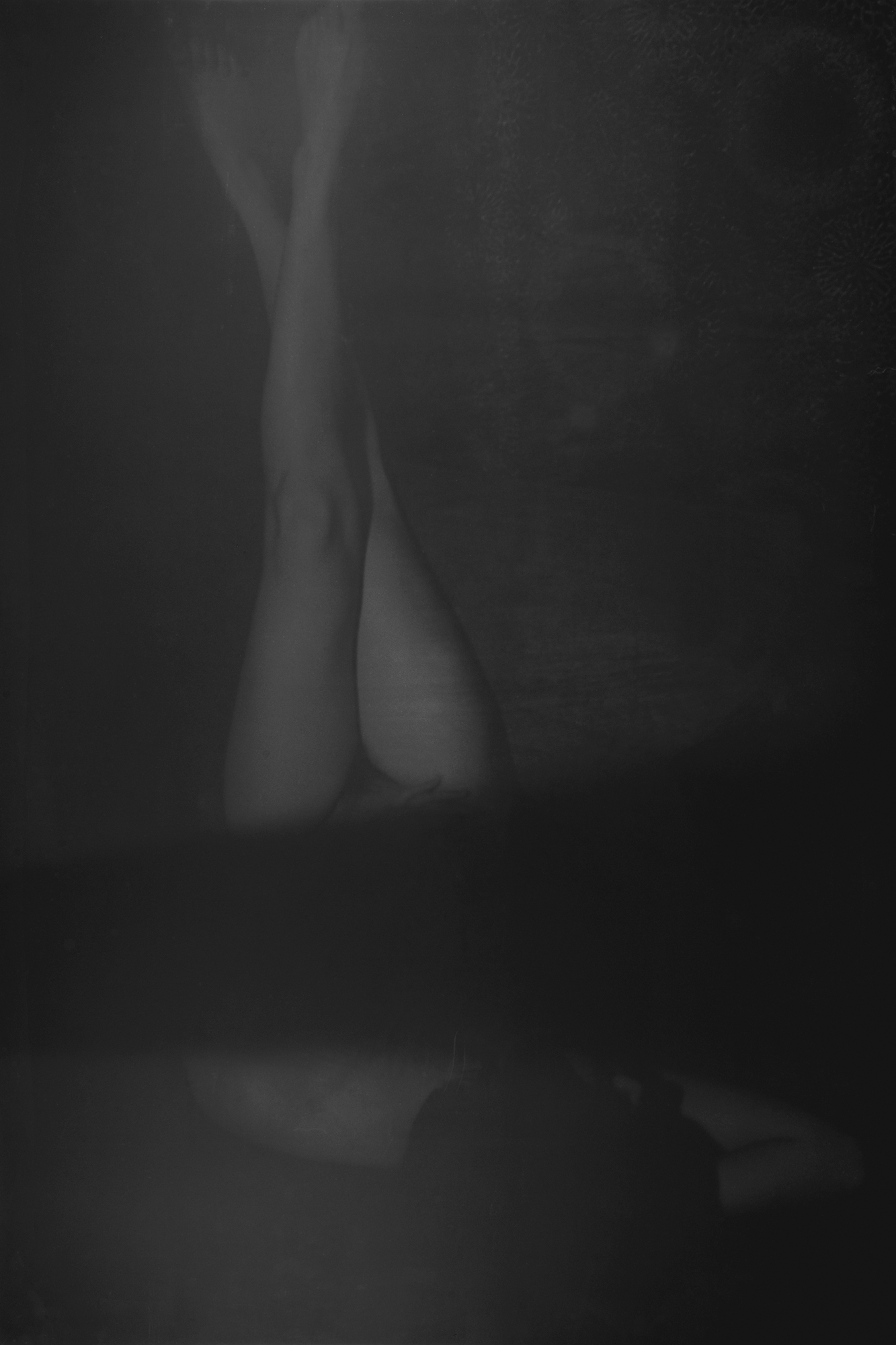

Among the distinguishing characteristics of Braeckman’s work is the lack of eye-contact. When human figures appear, they are typically turned from the camera, as if evading the photographer. Faces play a secondary role to torsos and arms and bodies, of subjects in seemingly candid positions. “When you see a face, the photograph becomes a portrait,” says Braeckman. “The view of someone’s eyes influences the entire image. The people in my photographs are never models. I never stage scenes.”

“When you see a face, the photograph becomes a portrait. The view of someone’s eyes influences the entire image”

Because of the frequent absence of the human figure, his photographs are subjective standoffs with natural and constructed space. The photographs walk into the corners of the earth or of a room, they séance with dead-ends. They indicate the pounding headache of staring at the corridor floor. Many of Braeckman’s photographs appear stolen or barely preserved: a mattress without bedding, a chandelier over a stained carpet. Dim, as if considering the act of disappearing. “Of course, I’m there,” he says. “But the relationship between me and the surroundings isn’t visible. I collect feelings.”

Occasionally, Braeckman teaches and notices his students trying his techniques. They present him with photographs on matte paper, black and white, and say that they’ve done it in his style. Braeckman recognizes the formal aspects of his photographs but does not see the psychological. A kind of place he refers to as “movement in stillness”. In these student works, he wants to see “an artistic choice”.

He emphasizes the physical experience of viewing artwork, which is particularly important for photography. “When you see a painting in a book or on a screen, you still understand that it exists as a different material shape outside of that,” he says, “but not with a photograph.” He thinks of his own books or catalogues as memories of the actual art.

“People want stories—about how the photographs are made, the places I take pictures, about loneliness. But I don’t think any of that is important”

The physical experience of the exhibition space also informs the scale of the photographs and the pauses Braeckman leaves between them. In the tall, contemplative halls of the Biennale’s Belgian Pavilion, his photographs keep a distance from one another. They are large, immersive—the word most often used to describe them is “monumental”. Braeckman has just had two new exhibitions up simultaneously. At Bozar/Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels, he continued the large scale from Venice, aligning his photographs with the sweeping curves of Victor Horta’s art nouveau architecture. At his second exhibition, Braeckman used the contemporary exhibition space of M-Museum in Leuven to also present smaller prints, stretched across long exhibition cases, on delicate paper folding at the edges, requiring the viewer to come in close to try and see. A video installation in a separate room further complicated the desire to capture an eluding stillness.

Braeckman never considers who may encounter his works. The photographs are not provocations, he insists, though they make some people angry with the questions they leave unanswered. Why a chair? Why emptiness? Why darkness? Is there anything there? “But that’s good,” says Braeckman. “My ideas of dealing with art aren’t about comfort and beauty.”

I met Braeckman for a coffee recently and he told me about the photographs he took while working in New York and Berlin in the eighties and nineties. In addition to the art he was making then, he also took “tourist photographs”, as he calls them, just for himself, not as a form of documentary. They happened to include situations such as the fall of the Berlin Wall. These photographs were never meant to see an audience or be presented as part of his body of work. They were photos he took so he could remember but they now exist as a record of history. He has since been encouraged to publish them but has so far refused. These photographs are too tethered to time and place.

When photographs are widely used for oversharing, Braeckman seems to enjoy keeping a secret. When photographs are instantaneous, he savours the time—the years—it takes to develop a single image or idea. Braeckman sees his process as a place of “protection” from art fairs, schedules and critics. It is an escape from the influence of outside pressures on his work. “My response is to go back to the darkroom,” he says. Then the artist excuses himself and steps outside for a smoke.