Drag’s history is centuries-long and its culture is far from monolithic. In fact, today there are more varieties and styles than ever before. But we don’t necessarily see this full variety in the mainstream. RuPaul’s Drag Race

—first aired in America a decade ago and launched in the UK for the first time last month—is responsible for introducing contemporary drag to a broad audience, many of whom will have never attended a ball or seen a queen in real life. Not since Paris Is Burning—the 1990 Jennie Livingston documentary that inspired Madonna’s Vogue, and which is recently enjoying a Netflix revival—has drag’s creativity and culture been so sought after. So what does the new demand for drag mean for the originators of the scene?

“You can’t just walk into a space and start taking photos without building that trust”

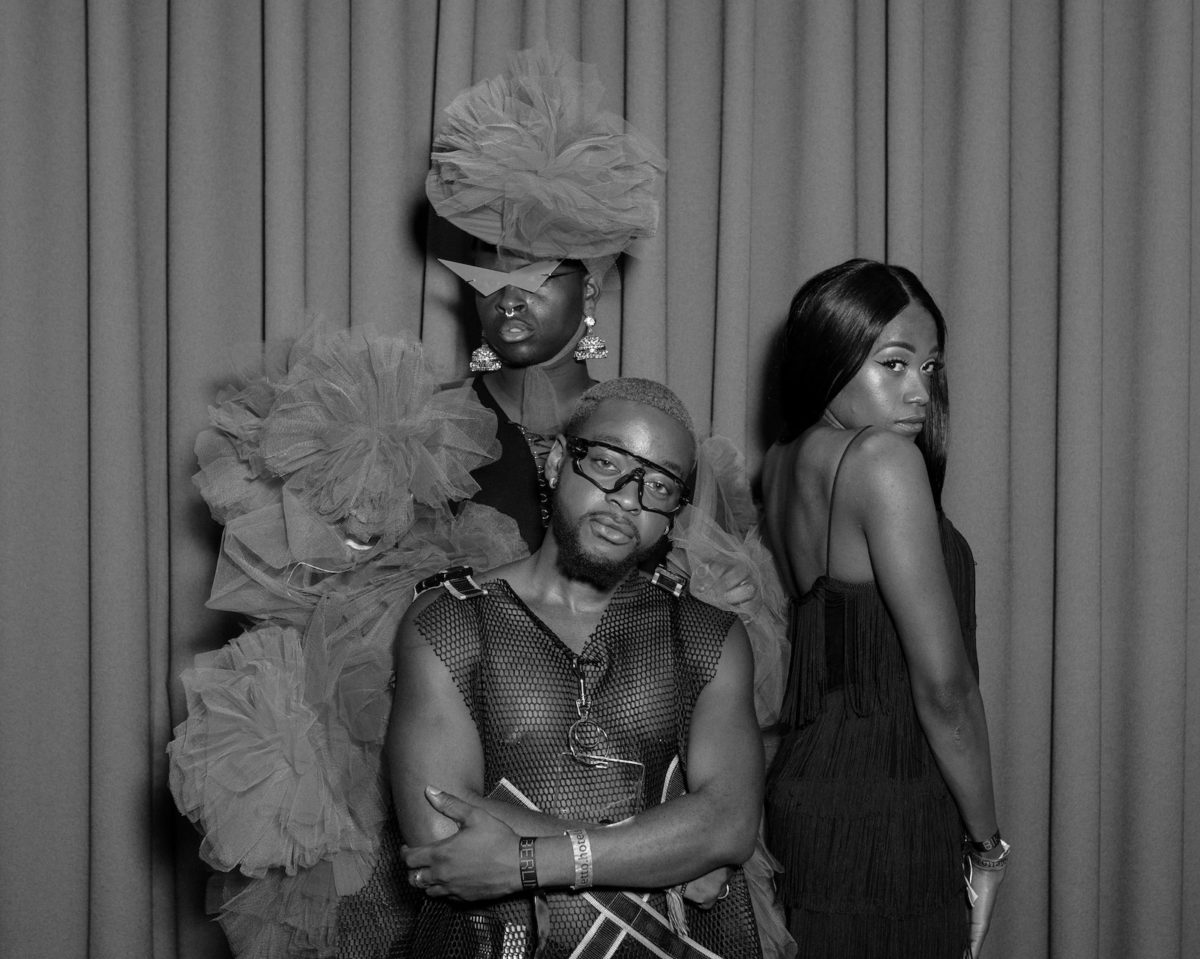

Documenting drag has always been an important part of the culture—it has preserved creations that will never be seen again, and it’s given communities visibility, where they have often been marginalized in society. On show at Foam in Amsterdam until 3 December, is an exhibition of photographs by Dustin Thierry, documenting the Dutch ballroom scene from 2013 to the present. A tradition that has been a form of expression for LGBTQ people since the nineteenth century in America, Thierry’s portraits show the contemporary ballroom scene as it has been revived in recent years, in cities including Amsterdam, Berlin, London, New York and Paris. The artist sees this scene as distinct from the mainstream idea of drag, and his work points to the discrimination against black and queer people as much as it celebrates masquerade as an art form.

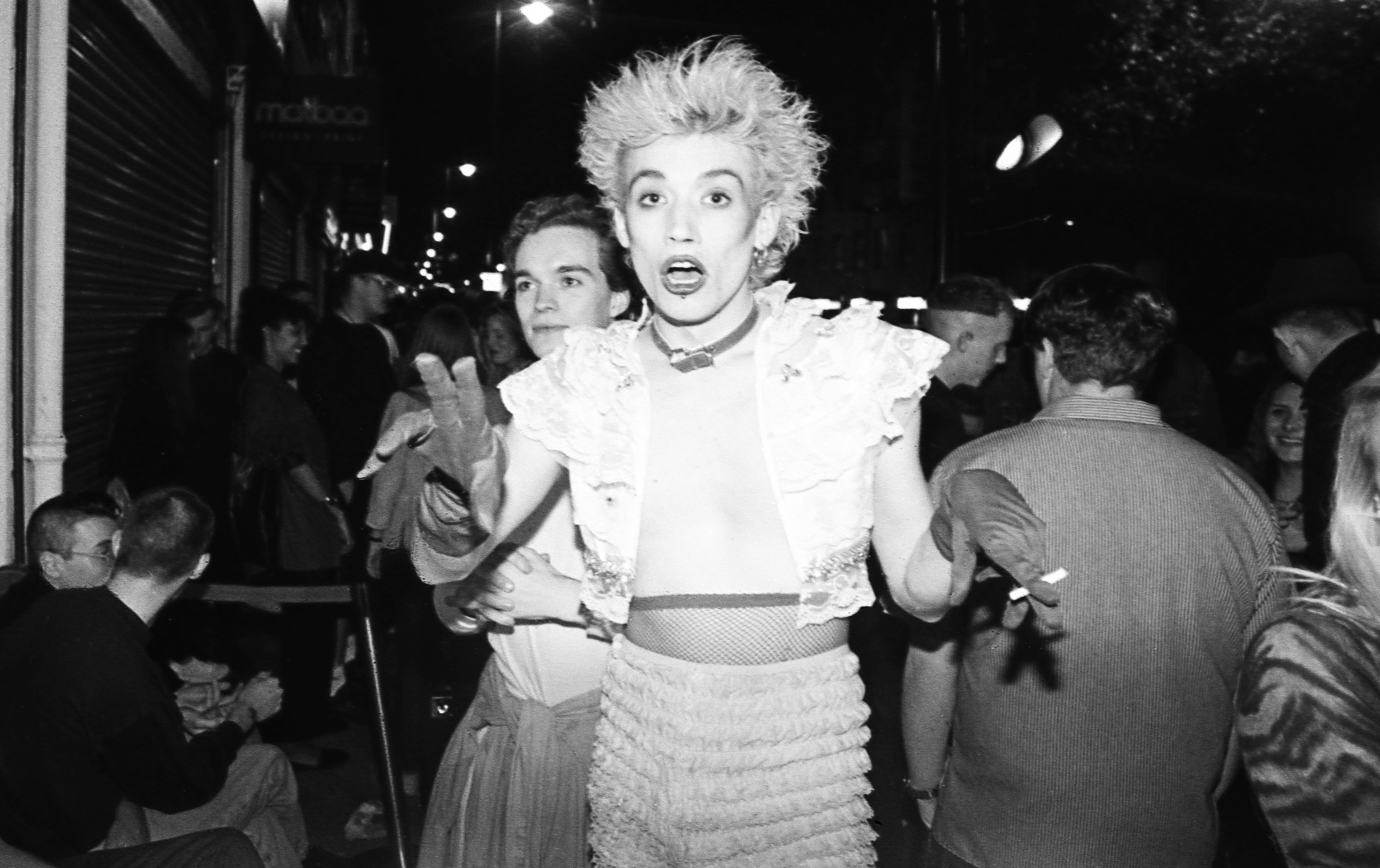

Adam Frost at WIMP, London 2019; Photo by Damien Frost

Damien Frost has been photographing drag in London since 2013, starting by shooting portraits late at night on the streets around Soho and the East End. “After a while it felt like I was documenting a close-knit community and I was fascinated by both the transformative and ephemeral nature of many of the looks—where people would spend hours crafting something that might also be days in the planning, only to wear it for a few hours one night and then never again.”

When Frost began to take the pictures that he would later publish in a book, Night Flowers, “there was a small explosion of alternative and extreme-drag and club kid looks—probably influenced by shows like Rupaul’s Drag Race but also more importantly tied to the increasing popularity of tools like Instagram, where drag communities could be inspired by riff-off, beg, borrow and steal each others’ looks.”

“I was fascinated by both the transformative and ephemeral nature of many of the looks”

Frost was an outsider when he started out photographing portraits in dark alleys. Now he’s a regular at clubs where he invites his subjects to sit for portraits—though they’re still unplanned and improvised and he never knows who he’s going to shoot. “I purposely situate my subjects in an environment that doesn’t look like a club, so I’m largely taking them out of their context already, but it’s important to me that people see the images as documentary photography and, as such, real-life. These aren’t models styled by a team of stylists in a studio—they’re walking works of art exploring and transgressing boundaries and just fucking with expectations, and I find that incredibly fascinating.”

Frost’s photographs capture a hidden, more underground side of the scene, darker and distinct from the kind of drag that makes its way to the mainstream. “I’m less interested in documenting ‘traditional drag’—there’s a lot of craft and artistry involved in traditional drag, but I’m more fascinated by drag that goes beyond the idea of passing for the opposite gender and rather transforms the person into a third space that’s beyond ideas of binary gender and, as such, is more transgressive and harder to define.”

- Photo by Magnus Hastings

Magnus Hastings—a British photographer who has photographed the drag scenes in Sydney and Los Angeles—agrees that “its only really a certain version of drag” that has become mainstream. As drag begins to appeal to a wider audience, it might lose some of its vital political and subversive power. As Hastings says, “it annoys me when it gets made more family-friendly. Real drag is kind of punk rock and it is unapologetic and in your face. San Francisco drag, which is extremely creative, is an important part of drag for me and I have constantly showcased it. But it gets very little attention in the mainstream because it’s dangerous and sexual and doesn’t fit in with the tongue snapping, death dropping, catchphrase forcing new normal… I have had battles with people trying to keep it PG which isn’t the point… I actually think Rupaul’s Drag Race is pretty good at not doing that and remains pretty on your face, which kids clearly love—it’s just the parents, as usual, wanting to reimagine an art form in a convenient, vanilla way to protect their delicate offspring!”

Hastings started shooting portraits of drag queens early in his career and they’ve been the focus of his practice since 2003. “I always say I am a participant not an observer,” he says. When he moved to Sydney in the early 2000s, the scene was thriving and vibrant. “Vanity Faire and Courtney Act were to become my muses and at the time they were threatening the face of drag, as they were genuinely fucking with people’s heads, and making straight men uncomfortable.” Instagram has contributed as much to changing tendencies and trends in drag as shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race, with Instagram followers playing the role of ballroom judges or audiences.

- Photo by Magnus Hastings

In the last ten years, the commercial industry started to tap into the marketing power of drag superstars, from global brands like M.A.C and Absolut to Facebook and even Peta. Hastings recalls when friends started to be asked to do TV ads, and one particular champagne campaign that featured Vanity Faire. “It was a strange phenomenon. On the back of Priscilla Queen of the Desert, the Australia Tourist Board really pushed the drag and gay side of things, encouraging gay immigration, but at the same time there was a sort of backlash, with lots of gay-bashing going on in the gay areas.”

Hastings’s observations point to the discord between what’s celebrated on screen and what drag queens experience on the street. “I’m suspicious of saying that drag is accepted by the mainstream. It’s definitely got a lot more traction but I feel it’s sometimes treated as a novelty and reduced to ‘camp fun’, but this glosses over the fact that people walking down the street or travelling on public transport are still heckled, called-out, threatened and attacked for dressing how they do,” Frost adds.

Despite the increasing visibility of drag, in reality, the closure of many famous clubs and pubs supporting the community in London has had an impact on the scene. The Vauxhall Tavern is one of the few iconic venues that is still a hub for the drag scene. “Drag shows have always been well supported, however because of the quality and diversity of artists it now attracts a very good appreciative audience. The drag scene is the biggest area of change we have seen in recent times. It has transformed itself to a credible level of performance. Our Sunday cabaret shows with Queens of Cabaret are the best the London LGBTQ scene has to offer,” the venue tells me.

“I feel it’s sometimes treated as a novelty and reduced to ‘camp fun’”

Emily Rose England started to photograph East London’s club scene a decade ago. “I already had a few friends here who were involved in the club scene—either putting on nights, performing at them or attending them, so I would often go with them. I guess from there it just snowballed from a teen going out with her friends who started to document life around here, to becoming part of this wonderful community, which has become a huge part of my life. The photographs I was taking of life around me have become an important documentation of the drag and queer community at present in East London.”

England has photographed at VFDalston, East Bloc, The George & Dragon and its reincarnation, The Queen Adelaide, where she also works behind the bar. She also runs a night, Sassitude, at Dalston Superstore. England emphasizes that as someone who photographs the scene regularly, trust is important. Misrepresentation can come with mainstream media attention—and a central part of drag culture has always been a familial bond, where many members of the community might have been rejected by their own relatives.

“I am close friends with a lot of my subjects—one of the perks of being in such an amazing, tight-knit community—and they love being photographed by me. I think trust is an important part of that though, because we have this existing close relationship, they trust that I know what photographs they will and won’t like, and if there’s a specific photograph that makes them feel uncomfortable. They know the photographs are taken on both our terms, not just my own, and that’s incredibly important. You can’t just walk into a space and start taking photos without building that trust and having that existing consent—especially if you are coming from outside of the community—and expect your subject to be ok with that.”

England’s motivation as a photographer is “documenting a community who historically has been and still often is under attack from people who would rather we didn’t exist”, she explains. “Sometimes documenting what we do and making sure there is a lasting record of this beautiful amazing community is one of the ways in which we can fight this—as we are making sure that we won’t be silenced in any shape or form and that we do exist and are here to stay. I think it’s important for those of us from within the community itself to do this—as often when people from outside come in they will already have preconceptions in their mind of what they want to show or capture through their work, which largely ends up with the queer and drag community being exploited for someone else’s agenda. In regards to making sure that they are understood outside their context, I think because we come from within the community itself and are involved within it, we often take extra care with how it’s presented, who’s wanting to use the images and what for. Even if it means losing work, it’s very important to me to ensure that my subjects and the community aren’t exploited for someone else’s gain.”

“I think shows like Drag Race have helped people accept drag more and educate on topics such as gay history. Realistically it is one of the only well-known programmes out there to feature predominantly gay men and show them in a positive light, which helps with the acceptance of gay rights in society as a whole. However, these shows are often presented as the be all and end all of drag, when in reality it’s only a small insight into it,” England continues.

“The drag community is very inclusive, and includes cis women, trans and nonbinary queens. Whilst there have been a few trans contestants on Drag Race, they often end up leaving soon after coming out or coming out after the show ends. And RuPaul himself has been known for his misogynistic and transphobic comments. It’s also a very polished version of drag. In London and Manchester drag tends to be a lot more conceptual, performance art based and a little rough around the edges, which should be celebrated and included just as much,” she points out.

- F.L.T.R. Matyouz LaDurée, Vinii Legendary Father of the House of Revlon, Gigi Da Blizzard Revlon at the On The Cover of Vogue Ball under direction by Zueira Mizrahi, Berlin 2018, from the series Opulence © Dustin Thierry

For Hastings, there are also positives to the way that drag has become better known. The role of photographers from inside communities has also been to represent drag in a celebratory way, and as an art form “which is the normal perspective now”, he notes. There are other reasons that drag’s mainstream appeal could be beneficial, as Frost comments. “I’d like to think that having it in the public consciousness would help humanize it and make people less apprehensive about it.”

At the same time, he says, “drag still has the ability to shock. There’s a disruption and palpable feeling of electricity when someone is walking down the street dressed up and owning it, that still has the ability to turn heads and stop people passing by.” It’s this power that’s at the heart of drag and has ensured it has survived and thrived, whether the mainstream is paying attention or not.