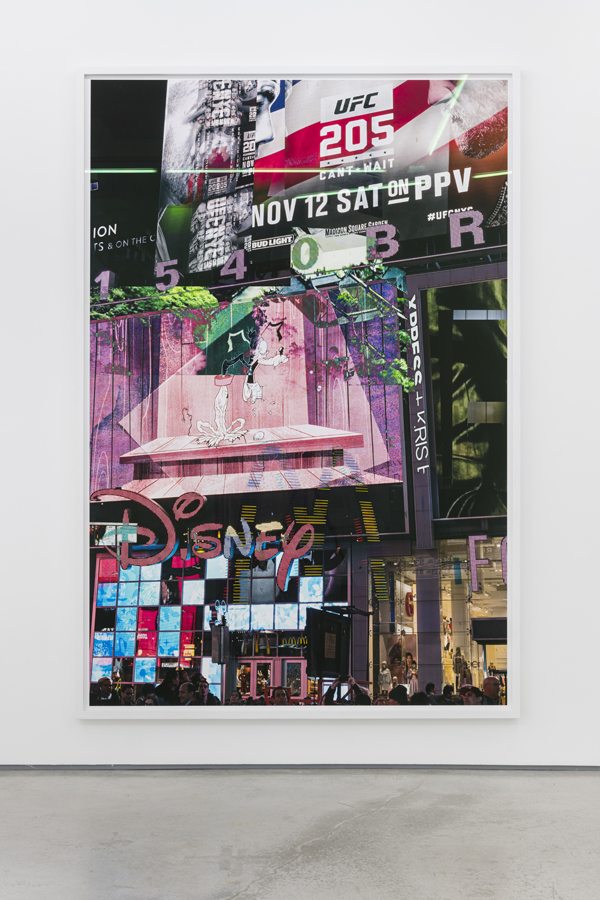

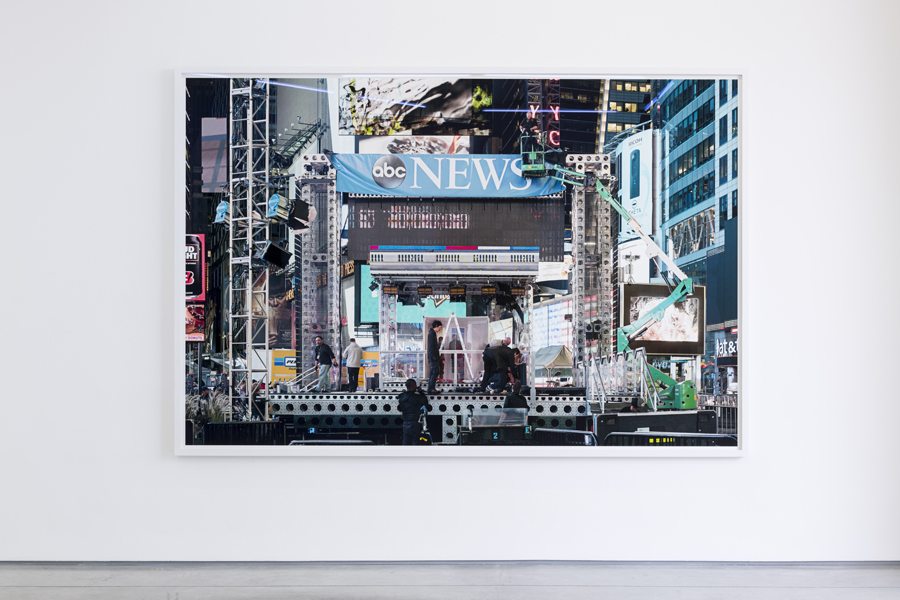

Where do we, and our digestion of images, information and facts, stand in the age of digital excess? A recent show at Rod Barton gallery in London brought together two artists—Kristian Touborg from Denmark and Moritz Wegwerth from Germany—to consider the current position we find ourselves in. Wegwerth’s images focus on Times Square, as workers disassemble the stage after Donald Trump’s election success, surrounded by gaudy, flashing advertising imagery. Touborg creates imagined archaeological items from a near future society. Here, they talk about data collection, their visions of the future and their reasons for staying positive.

Can you tell me a little about Instant Excess at Rod Barton?

Kristian Touborg: Instant Excess was an intersection of visual streams. It was an exposure of how visual imagery contains its own strata and how the works originate from our belief that what catches the eye in the street is a compilation of layers.

We seek to simultaneously expose and exercise the complex and incessant systems that imagery flows in at this point in time, framed and enunciated by the internet. Instant Excess is a verbalization of the foundation for both our practices: How can an accumulation of artistic frameworks, which focus on diverse means of visual production, which are interwoven with digital and psychical archival methods, contribute to an understanding of the visual culture of our contemporary society?

Installation view

You were both very well-paired in this exhibition, and were described as working as a visual critic and a visual anthropologist, each exploring similar territory by very different means. Were you in dialogue before the show, were these works formed with a consideration of each others’ practices, or is the match more of a coincidence?

KT: The exhibition is not the outcome of a random juxtaposition of two artists using the same reservoir of visual material, but much more pivotal to us—the exhibition is the outcome of a pre-established, long-term and ongoing dialogue between Moritz and myself. This conversation is not rooted in the production of specific artistic projects, but is initiated as a dialogue that enriches and guides our bodies of work separately. A joint project then came naturally when it was proposed, as we already share this exchange of thoughts and ideas. Instant Excess kept in mind Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s line of thought, as we notice how we influence each other as our data and information creep in only to be merged into our separate practices as the preceding dialogue refers back in time to endless hours of discussions on art and life.

Moritz Wegwerth: Excess made me think of Byung-Chul Han’s book, Hyperkulturalität (Kultur und Globalisierung), which I was reading lately. He talks about everything as being interwoven, a step further beyond hybridity. That is what I think is at stake.

The ideas that came up in the exhibition are very rooted in this current moment in time, where individual behaviour and thought feels very led and manipulated by technology, and where fact and fiction are incredibly blurred. Where do you see this going in the future?

KT: We should expect extreme changes, as the technologies of the future are being developed as we speak. Ranging from virtual and augmented reality in our everyday life as well as environment reinvigoration and AI. Immediately I think of the movie Her—about a man who develops a love relationship with an intelligent computer operating system, which is personified through a female voice. It’s the same type of story that’s told in Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld from 1973, which has recently been made into a series by HBO. This scenario in which technology influences and becomes a central part in how our feelings and emotions are created in a near future stands as a constant reminder to me of how important the true physical and human relationships in life are. I find the way the scenarios unfold in science fiction universes simultaneously scary and possible as technology evolves, and the more I think of it, the more I feel an importance of standing up for the analogue in a world where technology influences almost every aspect of our everyday life, including the production of art.

I’m also fascinated by the possibilities technology brings into the production of art, but it’s pivotal to me to anchor my work in the dreamy seductive authenticity that only materials processed by the human hand can hold. How love can only be exchanged between humans, and how brushstrokes and a visual eloquence of an artist only can be simulated and not replaced by technology—at least not at this present moment in time.

But it fascinates me how artists can shape the future of technology and how we interact with technology, as well as how technology plays a role in the way artists express themselves.

Considering the news currently, data collection is being discussed in a different way to perhaps even when you were making this work. Is this something you’re already both responding to in your practice?

MW: Considering the news very currently, 25 May 2018, the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) decision has a huge impact on how data is being collected, but also distributed. Perhaps even more interesting for long-term implications is how individual countries and corporations are choosing to permit or restrict access to images that can be viewed—who has access to what as visual resources and who does not. The medium still is the message.

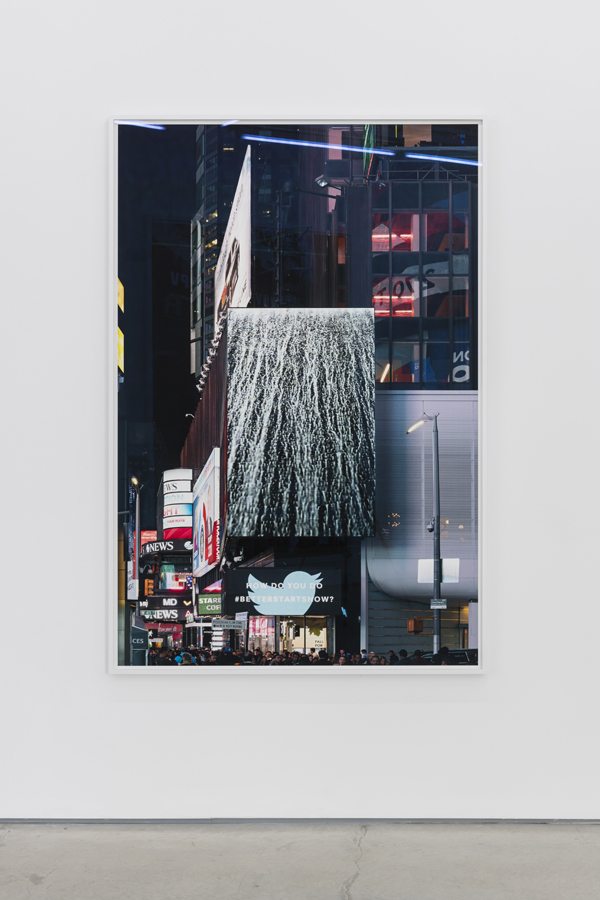

On the other hand, with a constant stream of information, I try to take some distance from that and to see it as a system itself and to see the mechanism behind the production. I look at documentation of life through the lens of the “revolution of images”, how they change, reflect and shape culture over time. Early civilizations used symbols, fifty years ago it was more text-based, and now we have come to tech images as our mass means of shared understanding. If there is one nexus in the world where this all comes together it is Times Square. There is a constant stream of images being generated, both put out and taken, and shared across the world. It took layers of complexity to get to where we are now, to give us the multi-perspective experience that we now live on a daily basis.

“It’s a question of who decides how and what to preserve from our digital footprints”

KT: In my work I try to dive into one of the biggest obstacles of a digitalized society: How do we create a lasting, immaterial storage of data? We are now at a stage where we have the means to reconstruct lost code. If the resources are used, we can change the question from how do we remediate the 1s and 0s, to a question of how we create lasting, democratic, immaterial storage. This means that how and what material should survive from our vast personal digital databanks in the long term are at stake. My work offers no quick fixes in this matter, but I wish to highlight the obstacle as it touches upon all of us as we save photos in our digital clouds, speaking about data as a metaphysical concept freed from material mass and commercial affiliation. It’s a question of who decides how and what to preserve from our digital footprints as well as who has the option of harvesting this information. And most important—who has the option of deleting everything in an instant.

- Kristian Touborg, Situation Symphony (Relief Panel) I, 2018

- Moritz Wegwerth, Betterstartsnow, 2018

Do you feel hopeful about the future?

MW: The interaction between images and reality and how tech images change reality and the future is under constant construction. I see it as very diverse.

KT: A few weeks ago I became a dad, so please let’s not talk CO2 or clashes of civilizations! I am, in general, an optimist, and I believe optimism is important in molding the future and creating possibilities. So let’s talk about the amazing things the future will possibly bring. In creating this body of work I discovered a glimpse of the incredible evolution within computer visions and the different approaches to it. Machines can now understand objects in a scene and create an impression of what is happening in it. Machines can analyse pictures on our mobile phones and understand the meaning of them; who and what is in the picture. We can interact with Siri.

“AI will play a big role in the future in art, which makes the analogue even more important than it is today, reminding us that we are humans”

This is a part of the AI development that I believe we have only seen a single bit of. We are standing on the train platform talking about the Shinkansen train that we know is approaching. And all of a sudden it passes by with the speed and the power of all winds and beasts on the planet multiplied. This is a frightening, fascinating and relevant thought, since we keep producing so much online data and constantly feeding the beasts with personal info (as Moritz mentions).

AI will play a big role in the future in art, which makes the analogue even more important than it is today, reminding us that we are humans. Dreams and visions are vital in the creation of our future.