As midnight approached on 24 May 1997, I was in the heaving Trans Europe tent at the Tribal Gathering festival in Luton Hoo, Bedfordshire. I was squashed between a sweetly bookish “old guy” (around 30), my schoolfriend Sophia, and a sweat-drenched raver; all of us buzzing, wide-eyed and waiting for Kraftwerk. When a synthesized voice finally boomed the German quartet’s introduction over the speakers, there was a collective roar of ecstasy; as soon as the first track, Numbers, counted in with ultra-sharp visuals (dazzling digits, reminiscent of Tatsuo Miyajima’s art), I was hooked.

I had first heard of Kraftwerk via my favourite techno DJs. Tribal Gathering’s bill was an all-night electronic feast, featuring names such as Orbital, Roni Size, Two Lone Swordsmen, Laurent Garnier and newbies Daft Punk. The Detroit tent powered down during Kraftwerk’s set, as a mark of reverence. By the time the robot doppelgangers emerged from behind the screens, my throat was raw with screaming for the men-machines. More than two decades on, that set still feels like it changed my life.

Electronic music wasn’t strictly “underground” at that point. Events like Tribal Gathering drew tens of thousands of revellers, and club culture had fired up the pop charts and filtered into high street fashion. Yet a mainstream disdain lingered around the notion of “live” dance music, assuming that it was soulless and visually dull: a blinkered attitude that belied the history and ongoing innovations of electronic forms. That hang-up now seems to be widely redressed, via thriving contemporary electronic music scenes, an array of mega-successful acts, and increasing consideration from galleries and museums.

Kraftwerk inspired a MoMA exhibition back in 2012; more recently, we’ve had the Vitra Museum’s Night Fever in 2018, and shows Sweet Harmony at Saatchi Gallery and Into the Night at the Barbican Centre, in 2019. Now, London’s Design Museum reopens post-Lockdown with Electronic: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers, an “exhibition banger” remixed from a 2019 premiere at Philharmonie de Paris Musée de la Musique.

- Jean Christian Meyer, from the collection Lunacy, 1993

On a sunny morning in late July, 2020, I am gazing at Andreas Gursky’s photo of a sea of revellers at Dusseldorf’s Union Rave (1995), just inside the entrance to Electronic. This time, my plus-one is my six-year-old son. A nearby sign offers a hyper-reality check: “The year 2000 is now history”. There is an immediate headrush of emotion, heightened by the pulsing soundtrack that accompanies our one-way tour through the exhibition; nostalgia is mighty intoxicating, but Electronic’s power is no mere retro trip. All of the artists here feel bestowed with, and connected by, future possibilities.

“Electronic sounds and visions have encompassed exceptional scope, from ultra-minimal aesthetics to grandiose showstoppers”

A display of early twentieth-century pioneers also makes the argument that electronic music, with its abstract, otherworldly qualities, is hardwired to create spectacle. On show is a 1930s Croix Sonore instrument, which looks and sounds as though it was designed to commune with the stars; there is also an homage to enduring icons, such as the Radiophonic Orchestra’s effortlessly cool Daphne Oram, shown painting data onto film, in Fred Wood’s 1964 photo.

Visitors are whisked deftly towards the dancefloor, which is where the heart of this exhibition clearly throbs, across a range of (Western) hotbeds: Detroit “Machine Soul City”, Chicago’s house parties, Berlin’s squat scenes, the British acid house explosion. This meltdown of hi-tech visions and social adventures sparks some fabulous alchemy, meaning that these “repetitive beats” actually keep on giving.

Celebrated writer and former editor of The Face, Sheryl Garratt documented the rise of electronic music in her excellent 1998 book Adventures in Wonderland (just released in a 2020 edition). She explained to the website 909 Originals, “It wasn’t just about music, or even the parties. It gave us the impetus to change the way we covered fashion, to discover a new generation of photographers, to start using new models, to bring in new writers, to cover everything from science to big social issues. For me, it energised everything.”

Far from being limited in range (that previous mainstream stereotype of “a bloke prodding a laptop on stage”), electronic sounds and visions have encompassed exceptional scope, from ultra-minimal aesthetics to grandiose showstoppers. On the latter note, while I’ve never really warmed to the proggy electronica of French musician and producer Jean-Michel Jarre, his Imaginary Studio display for Electronic is appealingly out-there (if only we were allowed to touch the “lazer harp”), bringing to mind his lavish live performances, such as the world’s largest outdoor gig in Moscow back in 1997, and a pyrotechnic-packed “Millennium” show at the Pyramids of Giza.

Electronic also gravitates from industrial to science-fictional themes, notably in the work of Detroit techno hero Jeff Mills, whose iridescent stage gear for The Visitor (his collaboration with Pentagram partner Yuri Suzuki) looks as though it’s been beamed into the gallery. Mills is another artist whose projects warrant an exhibition in their own right, including his film scores for titles such as Metropolis, his orchestral collaborations including 2015’s Light from the Outside World, and his contemporary art performance Life to Death and Back (2017): a film/ stage collaboration with French choreographer Michel Abdoul, shot in the Louvre’s Egyptian wing.

The show also demonstrates how DJ and producer specs can transform spaces meant for electronic scenes. London’s contemporary club scene, currently on hiatus, places cutting-edge design beneath party-goers feet, such as the main room at Fabric, which features a “bodysonic” dancefloor, with 450 bass traducers installed beneath burnished wood. One short-lived yet memorable London spot was the Pentagram-designed Matter, which ran from 2008 to 2010 within the Millennium Dome construct.

Elsewhere, Ben Kelly and Peter Saville’s designs for legendary Manchester venue the Haçienda are instantly recognisable, yet retain some near-mythological power. Visitors are also absorbed into virtual landscapes, such as Weirdcore’s visuals for Aphex Twin’s 2018 Collapse album and live sets: a brain-fizzing AI view of AT’s native Cornwall.

“It’s a weird realisation that the gallery is the closest that most visitors will get to raving for a while”

There is a seemingly infinite mix here, spanning and splicing genres from house, techno and hi-NRG disco, to footwork, ambient and EDM, yet there are also immediate, instinctive points of visual connection. Included in the exhibition are: the ubiquitous smiley, fashioned into a luminous riot shield by KLF artist James Cauty; the Haçienda’s yellow and black hazard stripes; and even the facial tension of someone lost in music, as in Jacob Khrist’s evocative photo of Berlin electronic musician and producer Ellen Allien.

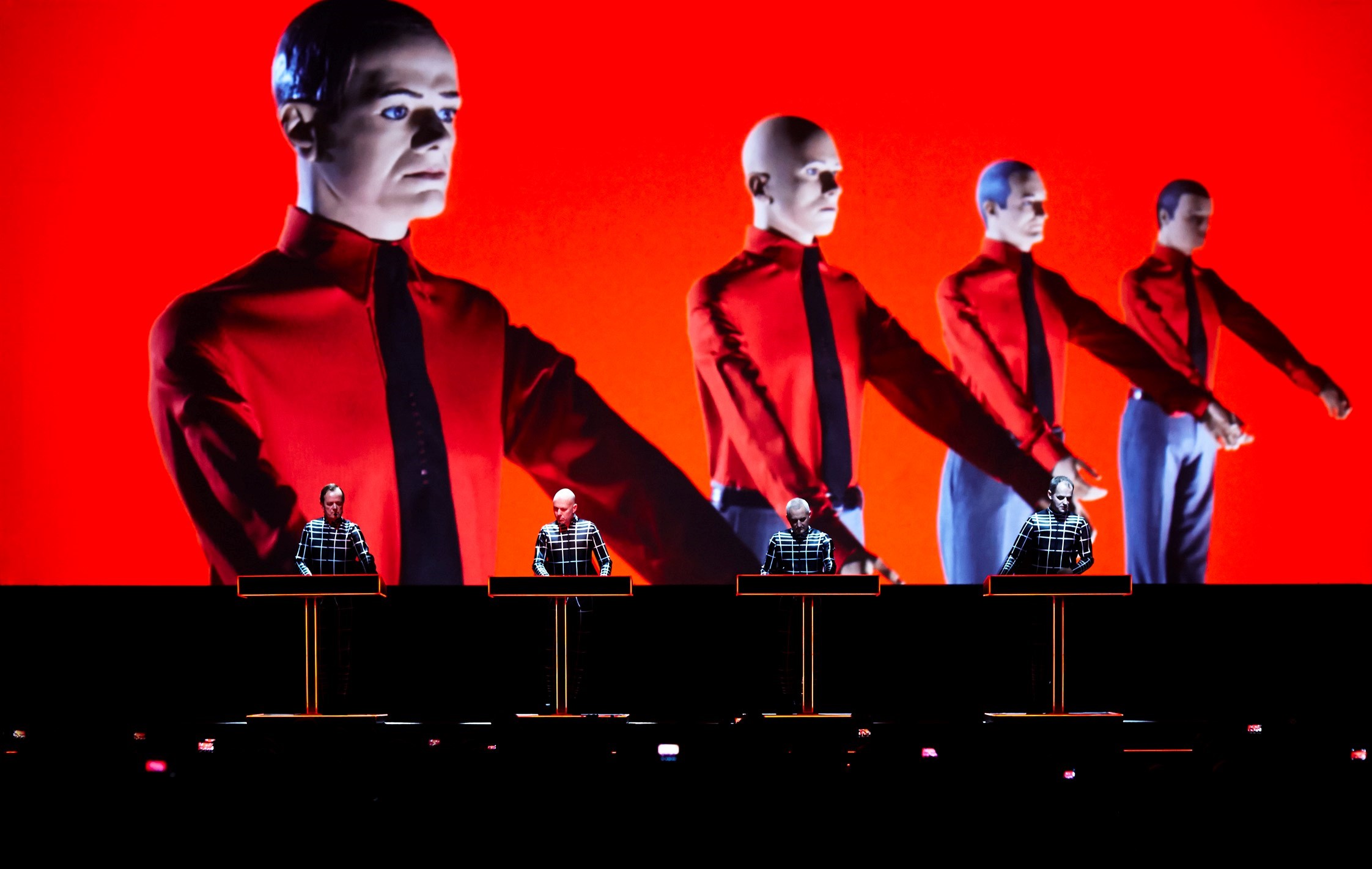

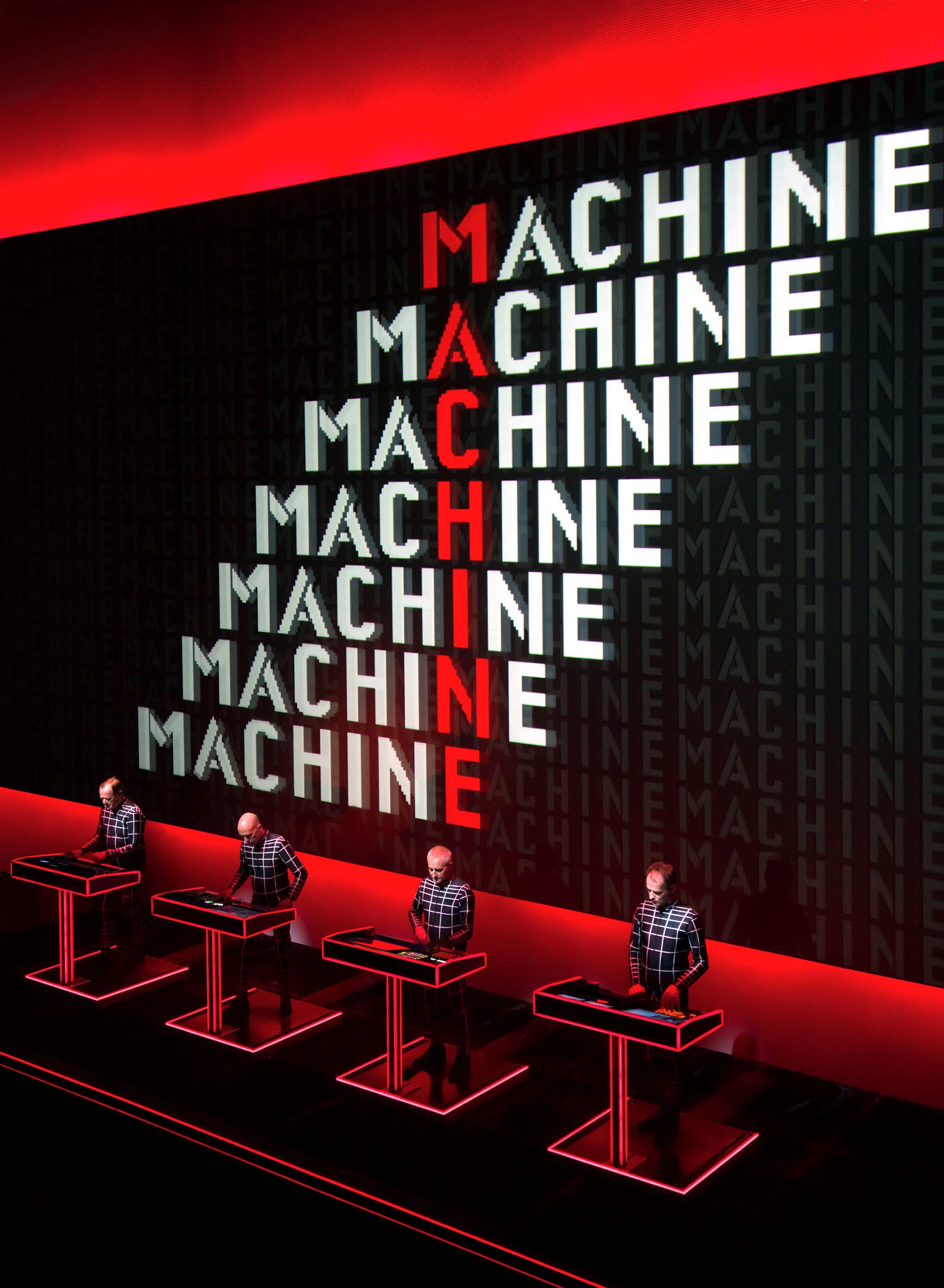

The classic red and black tones of Kraftwerk’s 1978 Die Mensch-Maschine are part of Electronic’s language, and viewers are enveloped in them for a 30-minute 3D screening of the quartet’s contemporary live visuals. For fans, this is some consolation for the necessary cancellation of Kraftwerk’s planned summer festival dates, though I’ve always found their rudimentary, weirdly visceral robots more exciting than their latest, uber-slick projections.

The immersive elements of Electronic are clearly vital. These are expressions that you should feel in your heart and guts. The CORE installation by 1024 Architecture is a gorgeous, mesmerising highlight, comprising 81 rods containing 24,000 sound-reactive LED lights, pulsing and undulating to Laurent Garnier’s playlist mix. It casts a wondrous spell, on adults like myself, and on my young son, who is yet to enter a club.

It’s worth noting that the French version of Electronic was subtitled De Kraftwerk a Daft Punk, while the British version shifts more focus towards our island’s rave scene, and Manchester-founded duo The Chemical Brothers. The remix makes sense, and I would hope that further global “mixes” of Electronic could follow, highlighting innovations across African, Asian and South American scenes rather than taking a specifically Western storyline. After all, it might be argued that Mumbai musician Charanjit Singh “invented” acid house with his 303- and 808-driven 1982 album Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat.

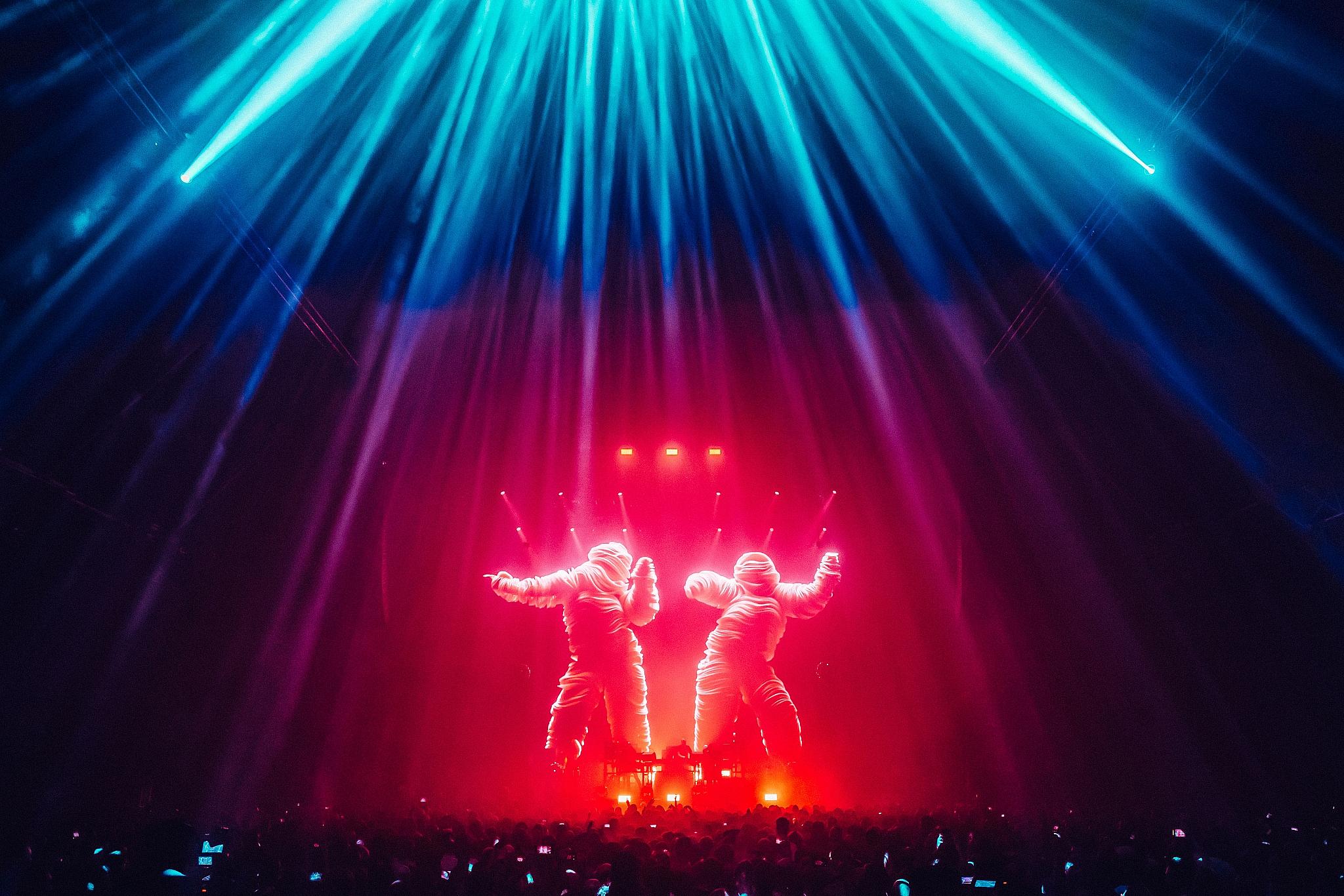

- The Chemical Brothers. Photo by Tony Pletts

Like many of the musician and visual artist dream teams depicted across Electronic, The Chemical Brothers go way back with their brilliant visual collaborators Adam Smith and Marcus Lyall, who have previously used monikers including Flat Nose George and Vegetable Vision. Their work together has resulted in gloriously surreal, spirit-lifting audio visual live shows, as also documented in the 2012 concert film Don’t Think. When I interviewed Smith in 2011, he described The Chemical Brothers’ music as “a dream come true in terms of making visuals. Their tracks are full of noises you’ve never heard before and incredible hooks. It’s a bombardment of the senses, with total heart and soul… We use a lot of colours magically emerging from darkness, and primary colours. A lot of that comes from working with primitive projectors in the early days, when we had to compete to stand out. Now we’ve got amazing Solaris light cylinders and hi-tech stealth screens and more intricate plans, but the style has remained.”

I swiftly steer my son away from a display of Chris Cunningham videos (“Ewww, what’s that?”), and towards Smith and Lyall’s final room: an installation based on their visuals for The Chemical Brothers’ blissed-out 2019 anthem Got to Keep On. It is a startling sensation, with blazing strobe lights, massive screen visuals of a dancer in a Leigh Bowery-style body suit, and the scent of dry ice cut with hand sanitiser. It is a full-on, twenty-first-century contrast to the “blacklight room” that was the centre-piece of Tate Liverpool’s Keith Haring exhibition over a year ago. It’s a weird realisation that this gallery is the closest that most visitors will get to raving for a while. It also feels like a statement that this cannot be the end. Electronic’s “future possibilities” extend to future generations: a circle of nightlife.

Electronic: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers

Until 14 February 2021 at the Design Museum, London

VISIT WEBSITE