In March 1848, strange thuds, scratches, and knocks began echoing through a cramped one-bedroom cottage in Hydesville, New York. The disturbances woke fourteen-year-old Maggie Fox and her eleven-year-old sister Kate from their sleep—and soon, the girls claimed the noises were messages from an unseen spirit. As the sounds persisted, their parents called on neighbours, who too heard the phantom raps. A consensus formed: a ghost was in the house, trying to speak. But their older sister Leah suspected a different truth. She coaxed a confession from the girls—they had been producing the sounds themselves, a trick of nimble joints and perfect timing. Rather than ending the performance, Leah saw an opportunity. She began staging the hauntings for paying audiences, launching her sisters into the public eye. By the early 1850s, the Fox sisters had become international celebrities and unwitting founders of a new American spiritualist movement.

It’s this origin story—equal parts hoax, belief, spectacle, and girlhood—that underpins The Missing Link in Modern Spiritualism, Emma Rose Schwartz’s solo exhibition at Derosia. Taking its title from a lesser-known text by Leah Fox, the show traces a lineage of feminine myth-making that stretches from 19th-century séance culture to contemporary expressions of fantasy, intuition, and mischief. Schwartz probes the tension between authenticity and performance, exploring how history itself is often shaped by the spectral—by rumour, storytelling, and the imagination of young women.

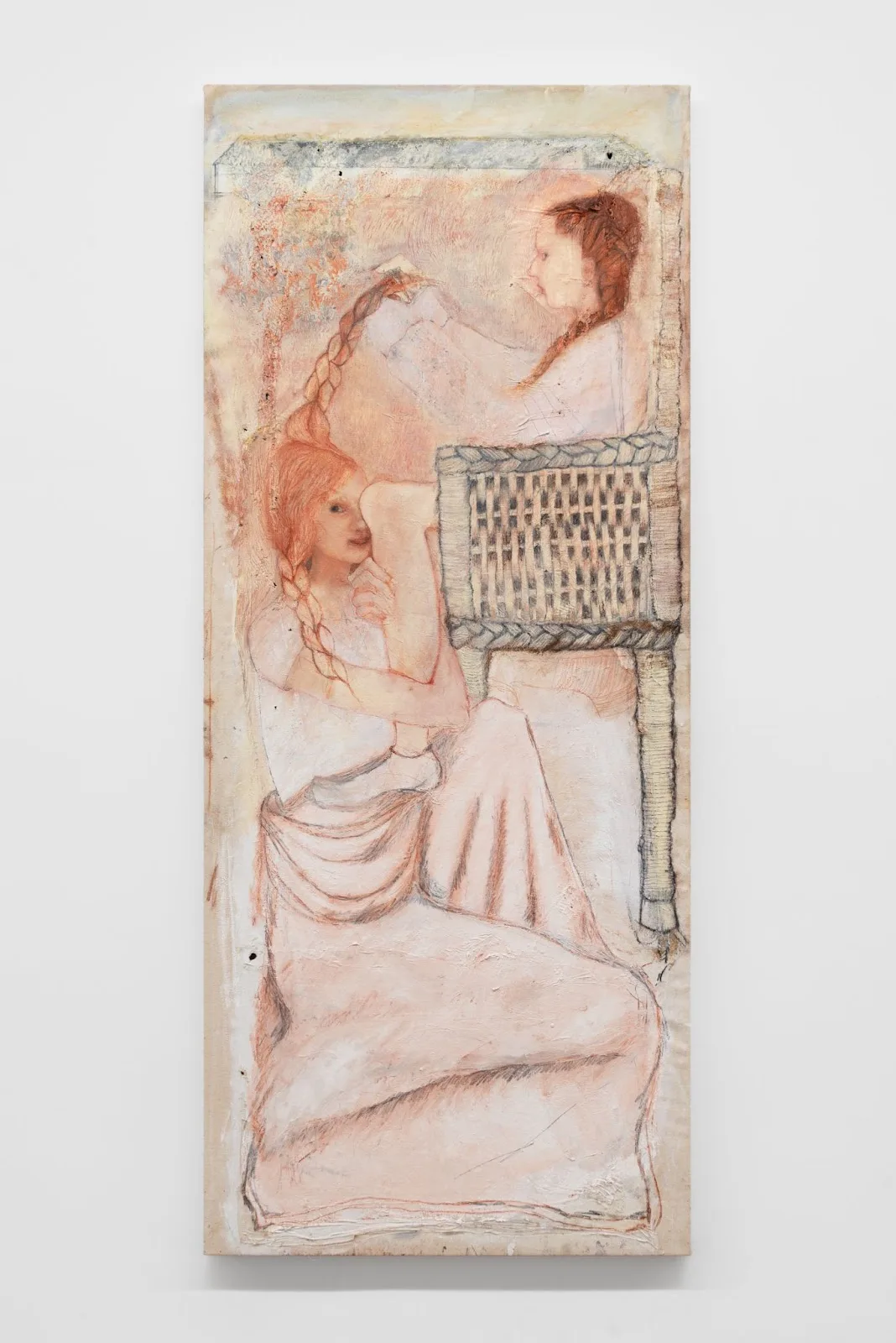

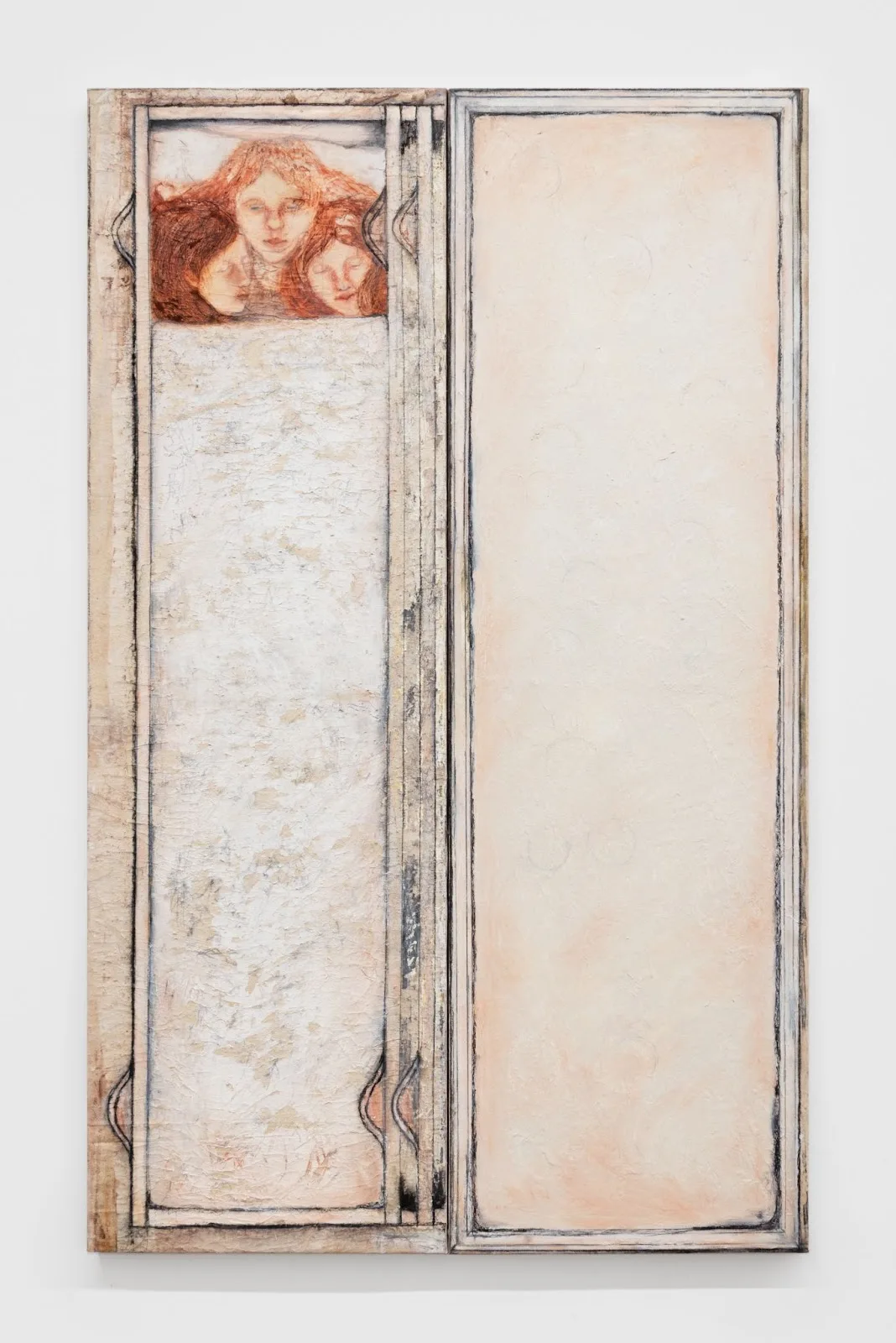

Throughout Schwartz’s canvases, red-haired girls with cunning expressions sprawl across wicker furniture, their beady eyes and sometimes-detached heads evoking both playfulness and unease. Braided hair recurs as a motif, as do female figures that, while not directly autobiographical, serve as echoes of the artist’s intentions for the work—fractals of the female self, refracted through time and symbolism. Morning Inside a Chest of Drawers (2025) captures the exhibition’s themes particularly poignantly in elegant shades of ochre-red and creamy white for the calm faces of the three pictured, female figures. As the Fox sisters’ taps and cracks permeated through furniture and walls, so do the figures, poking out suggestively from the storage piece in front of them.

Schwartz’s interest in these unruly girls—their cleverness, their perceived deceit—raises larger questions. “Why girls? Why not boys?” she asks. “Maybe we don’t hear about the boys because they’re not seen as capable of mischief, or maybe the girls are so desperate for power, or the experience of power.” That hunger—quiet, unspoken, yet pulsing beneath the surface—imbues the work. The girls in Schwartz’s paintings aren’t simply mischievous; they are architects of a minor mythology, wielding fantasy as both armour and authorship.

Schwartz spent the winter developing the work in an old schoolhouse in upstate New York, buried in snow and immersed in a world of pop-spirituality: her brother gifted her a Ouija board, she listened to paranormal podcasts, and explored the concept of table-tipping and ghost stories.

These attributes progressively seeped into her practice, combining with her enduring interest in domestic space as a uniquely American symbol—both as a lived-in reality and a cultural fantasy.

Her canvases are worked to the point of rupture: shadowy tones, distressed textures, and an unintentional patina lend the works an aged, uncanny feel. A recurring farmhouse appears at the top-centre of several paintings, referencing her Southern upbringing in Nashville and evoking the classic ranch house—a symbol of mid-century middle-class America, all horizon lines and dreams of ownership.

The pieces are suggestive insofar as they seem to encourage viewers to look deeply into the eye of mischievous subjects (the most curious perhaps arriving in Define Figment (2025)) and think about the storytelling that led to these works. In conversations with Elephant, the artist shared that notions of women’s role in spirituality actually inspired a certain level of interest in the Fox sisters’ story, “and why women might be more often associated with communicating with the dead, telepathy, and women’s intuition being this mainstream idea.”

This interest in the feminine mystique—its performative edge, its cultural persistence—runs throughout the show’s sinews and layers. In Wicker Rocker Sunset (2025), fiery layers of red hair tumble backward as a subject tosses her head down playfully, curious smile and bright eyes beaming at potential viewers. Across the exhibition, the viewer becomes complicit in this process of meaning-making. Each scene feels like the aftermath of something barely seen—half-revealed narratives that invite projection.

For Schwartz, these ambiguities are less about withholding than about opening: creating space for emotional and historical inference. The paintings become séance-like in their own right, inviting not spirits but interpretations to rise to the surface. The artist’s ghost stories are not about proving what is real or imagined, but about honouring the murky territory in between—a space where young women have long been at once mythologized and dismissed.

Like the Fox sisters themselves, Schwartz’s subjects hover on the edge of credibility. They are not merely representations; they are stand-ins for every girl who’s ever been told her instincts were irrational, her feelings too dramatic, her dreams too strange. In reclaiming this aesthetic language—of gothic Americana, spiritualist hokum, and domestic surrealism—Schwartz doesn’t just pay homage to a lineage of feminine trickery. She rewrites it, insisting on its power, its playfulness, and its profound place in how we understand the unseen forces that shape our lives.

Written by Emily Sandstrom and Sam Falb