In his new photographic sequence April Fool 2020, Erwin Olaf presents himself as a 21st-century Pierrot. White-faced, cone-hatted and attired in a sleek mac, the artist pushes a supermarket trolly through an abandoned carpark, passing a row of faceless corporate structures. Once inside the shop, he inspects emptied-out fridges and shelves, unwanted items tossed to the floor. An attendant restocking the bare freezers wears the same snowy visage and dunce’s hat. In the face of Covid-19, we are all fools.

- Erwin Olaf, April Fool 2020, 10.05am, 2020 (left). April Fool 2020, 9.45am, 2020 (right). Courtesy the artist and Ron Mandos Gallery

The series captures the anxiety and absurdity of the pandemic. Aged 61 and suffering from hereditary emphysema, Olaf was acutely aware of his own vulnerability. “When the pandemic started,” he recalls, “I thought that I would go bankrupt. For the first month, no-one picked up the phone, mail wasn’t answered.” Shooting April Fool 2020 changed all that. “The day after I made it,” Olaf explains, “I felt I could control the situation better. I was not paralysed anymore.”

“I can depict myself better because I’m getting closer to what I want to express”

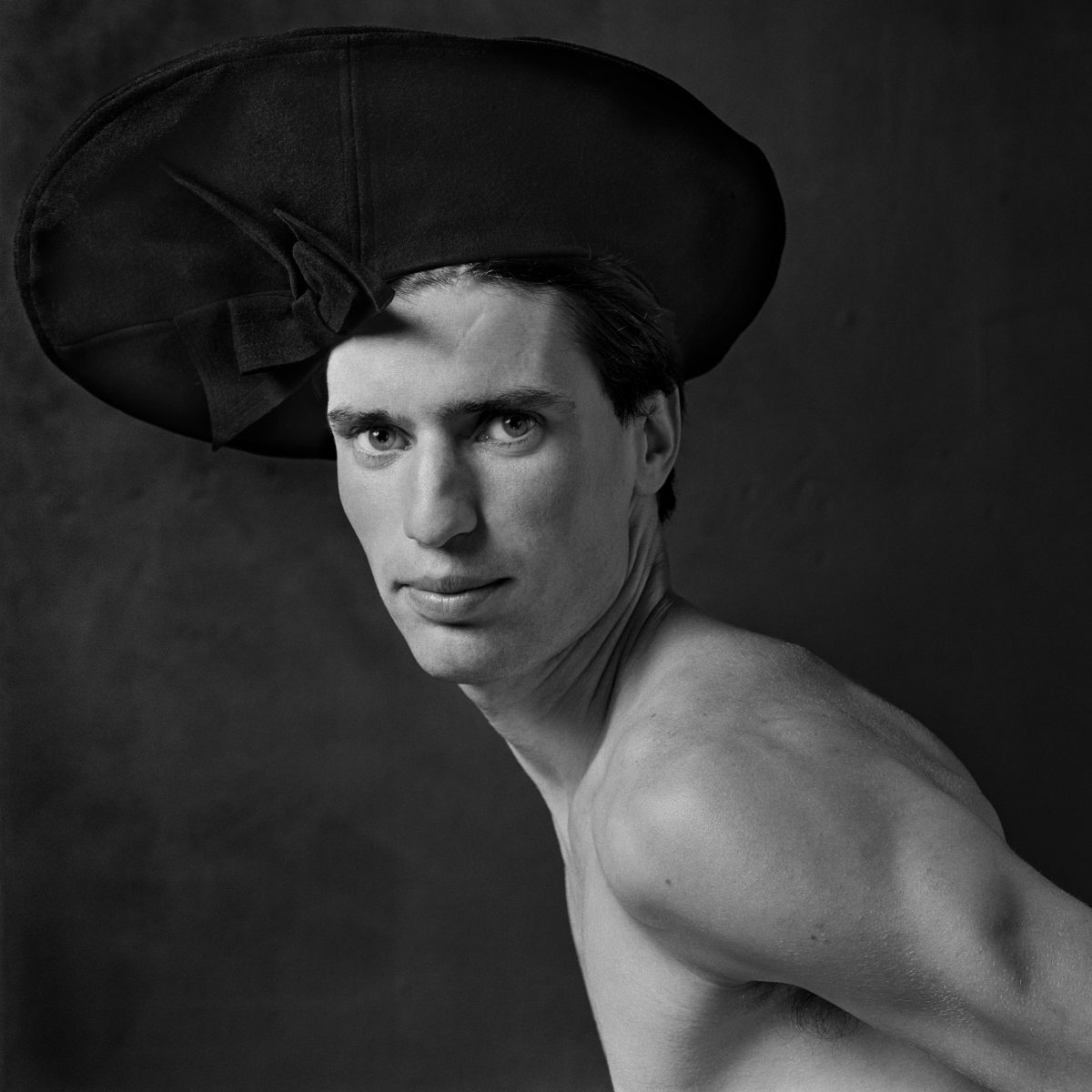

In the year since, Olaf has hardly paused. As well as April Fool 2020, he travelled to the Bavarian Alps to shot his project Im Wald and revived his Ladies Hats series (1985 onward), in which nude young men in extravagant headpieces pose in the manner of Dutch Golden Age portraits. All three will be exhibited in Galerie Ron Mandos, on Amsterdam’s Prinsengracht, this spring. And then, from May, the Kunsthalle Munich will host his career-spanning retrospective Strange Beauty.

- Left to right: Ladies Hats, Enzo I-FC, 2021; Ladies Hats, Jean II, 2020; Ladies Hats, Hennie, 1985. Courtesy the artist and Ron Mandos Gallery

Olaf’s career has been long and diverse, spanning almost every conceivable genre of photography, as well as video, installations, the 2014 Dutch Euro coin and a public toilet in Groningen. Olaf trained as a journalist, but he quickly traded the printed word for the reproducible image. His early documentary works, many undertaken for the Dutch LGBT organisation COC, were circulated internationally in queer publications. These attracted the attention of the mainstream press, which in turn provoked work for fashion brands. And Olaf’s success in these spheres allowed him to pursue his art.

“The human skin is for me a huge theme, an endless source of inspiration”

His images demonstrate the polished, poised perfection of fashion and advertising photography, while simultaneously puncturing the certainties of their concocted worlds. Olaf’s work often shocks: an image in the Royal Blood (2000) has Lady Di’s arm gorily implanted with the Mercedes-Benz badge from her fatal drive. The award-winning Chessmen (1988-89), meanwhile, presented 32 bound-and-gagged human chess-pieces, forming an obscene tableaux reminiscent of the photographer Joel-Peter Witkin. “The human skin is for me a huge theme,” says Olaf, “an endless source of inspiration.”

Witkin was a key early influence, along with Helmut Newton and Robert Mapplethorpe: all transgressive photographers who bridged raw flesh and subconscious desire. “Until that time,” Olaf explains, “the camera was not seen as an instrument you used to make art. They opened up a fantastic world.” But Olaf’s work has a liberated sexuality entirely his own. Joy (1985) shows an athletic young model clasp a spurting bottle of champagne to his crotch, his mouth agape in ecstasy. In the self-portrait Cum (1985), the titular fluid drips from Olaf’s own lips. “The body,” he says, “is just a body.”

- Erwin Olaf, Im Wald, Am Wasserfall, 2020 (left). Im Wald, Der Schwan, 2020 (right). Courtesy the artist and Ron Mandos Gallery

Compared to these full frontal assaults, Olaf’s recent work is more meditative. But it is, in its own way, exposing. April Fool 2020 features himself as the main protagonist, while Im Wald depicts both Olaf and his husband Kevin Edwards. Why this turn towards self-scrutiny? “Well, it’s cheap!” Olaf jokes. “It’s a kind of natural evolution over the last few years. I feel I can depict myself better because I’m getting closer to what I want to express.”

“Nature doesn’t have emotion. It doesn’t mind if you drop dead, if you suffer, if you are happy”

The new works also represent something of a loosening for an artist whose work is usually meticulously controlled. April Fool 2020 was shot in a single day, in what the artist describes as a “guerrilla” style; Im Wald is his first project shot on location outdoors. Prior to this a single professional disaster had helped shape Olaf’s working method. In the early 1990s, he was commissioned to photograph the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in the US Midwest, a gathering of Harley-Davidson bikers. “I had my artificial studio set,” explains Olaf, “and then everything went down: the lens broke, the camera broke, everything. I ended up with one journalist’s camera, a Nikon.”

Stung by this incident, Olaf retreated into the studio. For the baroque, monochrome-on-monochrome Blacks (1990) series, he worked with costume designers and make-up artists. By 2004’s Rain, he was building entire sets. “Everything,” says Olaf, “was exactly where I wanted it to be in my imagination.” In 2011 he won the Johannes Vermeer Award, the Dutch national art prize, but despite now having the means to shoot on location, his projects (while large in scale) remained largely indoor productions, akin to film shoots.

The influence of cinema runs through Olaf’s career. His images often suggest a larger narrative, whether the grieving housewives of Grief (2007) or the scantly clad man taking the knee in Palm Springs (2018). As a student Olaf would often attend the cinema alone. He was particular drawn to the “incredible sadness” of Luchino Visconti and the carnivalesque work of Federico Fellini. “Many art forms—music, painting, cinema, literature—can make you cry,” explains Olaf, “but photography, in my opinion, rarely does.” One of Olaf’s achievements is to grant photography a similar emotional thrust.

- Left to right: Erwin Olaf, Im Wald, Porträt IV, 2020; Im Wald, Porträt VII, 2020; Im Wald, Porträt XI B, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Ron Mandos Gallery

If film runs through April Fool 2020, Im Wald’s closest affinities are with painting. Inspired by the sublime landscapes of the German Romantics, it shows nature at its most oppressive. Figures are shrouded in mist, hidden behind foliage, dwarfed by waterfalls. We see Olaf among the trees, wearing a nasal cannula. The series takes particular aim at human arrogance towards nature, as epitomised by the tourist industry. One image shows selfie-stick wielding tourists attempt to turn the forest into their backdrop, unaware that Olaf’s camera is in turn capturing their own insignificance beneath the towering trees. “We think we are so superior,” he says, “but we’re actually so vulnerable, as we can see with the last year. I think nature is so interesting because it doesn’t have emotion. It doesn’t mind if you drop dead, if you suffer, if you are happy. It just thinks ‘go away’.”

Olaf is currently working on a project as concerned with connection as his 2020 works are with disconnection. In 2019, Olaf invited his models and muses from the 1980s and 1990s to his retrospective exhibitions in The Hague. “99% of per cent of them,” Olaf says, “have agreed to pose again. I’ve photographed two of them already, and it was really emotional. Our bodies all change, but their mentalities were still very strong, very liberal.” After four decades of smashing norms, Olaf is angling, unabashed, for one of the biggest unspoken taboos of all, ageing. “I think it’s fantastic,” he says, “to talk about time passing by.”