I’m standing in the Barbican Conservatory, a glass-roofed tropical oasis of more than 2,000 species of plants and trees built into London’s landmark brutalist estate. I’ve taken off my shoes. My eyes are closed. I’m breathing.

“Notice your breathing pattern: be aware of how you are breathing and where you are breathing from,” says Kalpana Arias in a guided meditation. “As you inhale, feel that prāna, that life force, coming up from the earth, through the soles of your feet. With every exhalation, focus on your sacrum, on that gravitational pull between your breath and the earth. The relationship that you are cultivating here is with your body and the earth.”

Arias is a climate activist who runs Nowadays on Earth, an organisation focused on nature connection in the digital age. She is also an ecosomatics educator. “Ecosomatics is understanding your body in relation to your environment, so that you recognise yourself as part of nature,” she explains. An extension of the yoga and mindfulness practices that are ever more popular in our stress-inducing societies, ecosomatics is increasingly becoming part of modern dialogues, with ideas around the breath permeating a number of current exhibitions, art installations and performances.

Arias’s Sunday-morning Radical Roots workshop in “ecosomatics and rewilding” is part of a programme of events linked with Our Time on Earth, the Barbican Centre exhibition in The Curve gallery (until 29 August). Billed as “an immersive exploration of radical ideas for the way we live”, it brings together art, science and activism to suggest creative solutions to the climate crisis. And it begins with your breath.

In a dark and curtained antechamber, an audio piece summons you into the space: “Breathe. Just one breath, shared by all living things. Breathe. Your breath comes from sea creatures and trees.” Spoken by the rapper Speech Debelle, the script was written by Andres Roberts, founder of the Bio-Leadership Project, a movement of people and organisations aiming to protect and regenerate our planet.

“The whole essence of this exhibition is to remind us that we are a living species within a living system, and isn’t that amazing!”

“We wanted to open the exhibition by inviting visitors to firstly connect to themselves, and remind them of the most fundamental aspect of being alive, shared by all living things, our breath,” says Caroline Till, one half of research agency FranklinTill and co-curator of Our Time on Earth. “The whole essence of this exhibition is to remind us that we are a living species within a living system, and isn’t that amazing!”

When artist Ersin Han Ersin, director of London-based experiential studio Marshmallow Laser Feast (MLF), spoke at the recent Our Time on Earth symposium, he too began his talk by asking the audience to close their eyes and breathe.

“Inhale. Exhale. That breath happens almost 17,000 times a day, and the air for roughly 9,000 of them come from trees,” he says. “When we contemplate the relationship between our breathing cells and the breathing planet, we encounter this great question: where does your body end, and where does the world begin? In breathing, the boundaries between our physical self and others, inside and outside, become blurred. We use this notion as the central theme in our body of work to remind everyone that you are not just an individual but an ecosystem.”

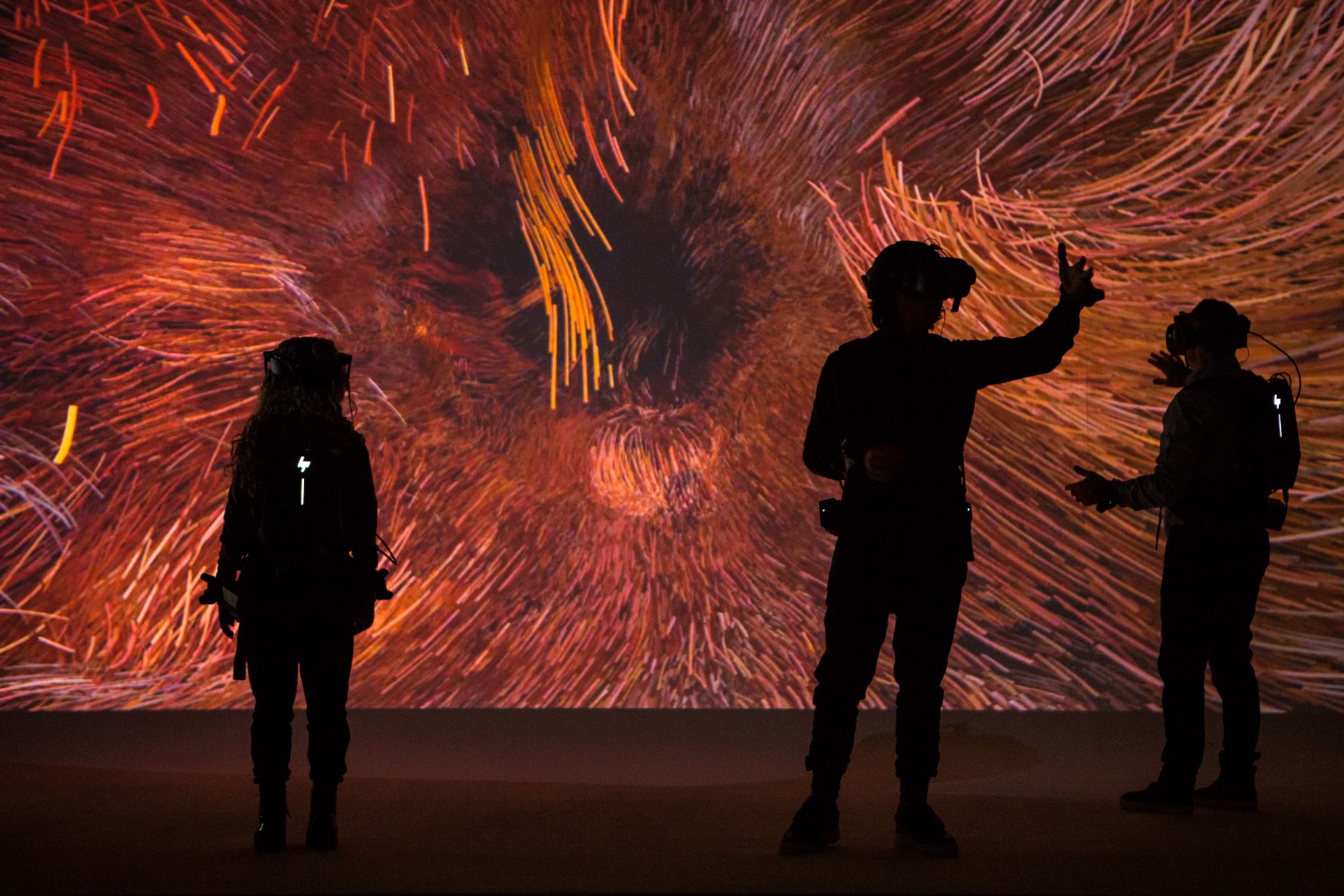

This relationship is explored in We Live in an Ocean of Air, MLF’s immersive, interactive virtual-reality installation on show at the ArtScience Museum in Singapore (until 2 October). It’s based around a giant sequoia tree. “You can see the breath coming out of your mouth and going in the tree; you can see the photosynthesis taking place,” Ersin explains. “It makes the link very potent. We aim to make the invisible visible, and to spark wonder and awe.”

At the Barbican, MLF is represented by Sanctuary of the Unseen Forest, a mesmerising video work that exposes the inner workings of a Ceiba pentandra tree in the Colombian Amazon. The tree pulses with energy, connected to the sounds of the rainforest and the rhythm of your breath. It’s an engaging moment in an exhibition that is incredibly thought-provoking, but at times also rather overwhelming.

Marshmallow Laser Feast & Andres Roberts, We Live in an Ocean of Air, 2022, installation view at ArtScience Museum, Singapore

At London’s Wellcome Collection, another melding of art and science is focused on the breath. In the Air (until 16 October) looks at how the air we breathe is “an ecological, social and political substance”, one that house viruses, pollution and toxic clouds. It’s starting point is poetic: Tacita Dean’s three-minute, black-and-white film A Bag of Air, in which a hot-air-balloon rises in order to capture the air “so intoxicated with the essence of spring that when it is distilled and prepared, it will produce an oil of gold, remedy enough to heal all ailments”.

“It brings together art, science and activism to suggest creative solutions to the climate crisis. And it begins with your breath”

There’s immersive video here, too: Air Morphologies by Matterlurgy (the collaborative practice of London-based artists Helena Hunter and Mark Peter Wright) surrounds the viewer ominously with oversized air pollution particles. But there is also quiet and serious contemplation, headphones on, watching Death by Pollution (2021), a documentary by Black and Brown Films looking at how air pollution caused the tragic death of nine-year-old Londoner Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah in 2013.

The similarly titled Into Air (until 29 July), meanwhile, is an altogether different exhibition. At St Cyprian’s Church in London’s Marylebone, the solo show by Singaporean artist Dawn Ng explores the passage of time in a highly tactile manner. Across films photography and painting, she documents the disintegration of large sculptural blocks of frozen pigment. “Into Air is a moment to explore how time slips and slides and is never forever, just now, like a breath: intimate and life-giving,” says curator Jenn Ellis, who also connected Ng with composer Alex Mills to create a site-specific “breath piece” for the show, based around his meditative scores.

“I quickly found that Alex and I were both exploring the same theme of ephemerality in our own artistic language: mine with visual colour, texture and form; his with breath, sound and musical structures,” says Ng of the collaboration that layers Mill’s choral breathwork over her time-lapse film of ice disintegrating.

“Across these myriad cultural contexts, the rather throwaway line “remember to breathe” has never resonated so deeply”

Their work and the setting combine to poignant effect. The piece was performed by five singers, who were “invited to move through the music to the rhythm of their own breath, not to an external tempo, and to find their own way through the piece,” explains Mills. “For the past few years I have been experimenting with how breath can help performers achieve greater creative, emotional and even spiritual expression.”

The idea of singing and breathing together is expanded in Oliver Beer’s video-performance work Composition for Mouths (Songs My Mother Taught Me)

that is currently on show at Manchester Art Gallery

, as part of British Art Show 9 (until 4 September). Pairs of performers create unusual duets by joining their lips in a tight seal, creating a single mouth cavity, and singing compositions based on their earliest musical memories.

“With nowhere else to go, their lungs are emptied out through each other’s noses, and, at the meeting point of the two voices, a third voice appears,” says Beer. “After all this time apart, for me, showing this work again is a cathartic return to being able to exchange air and ideas and music with each other.”

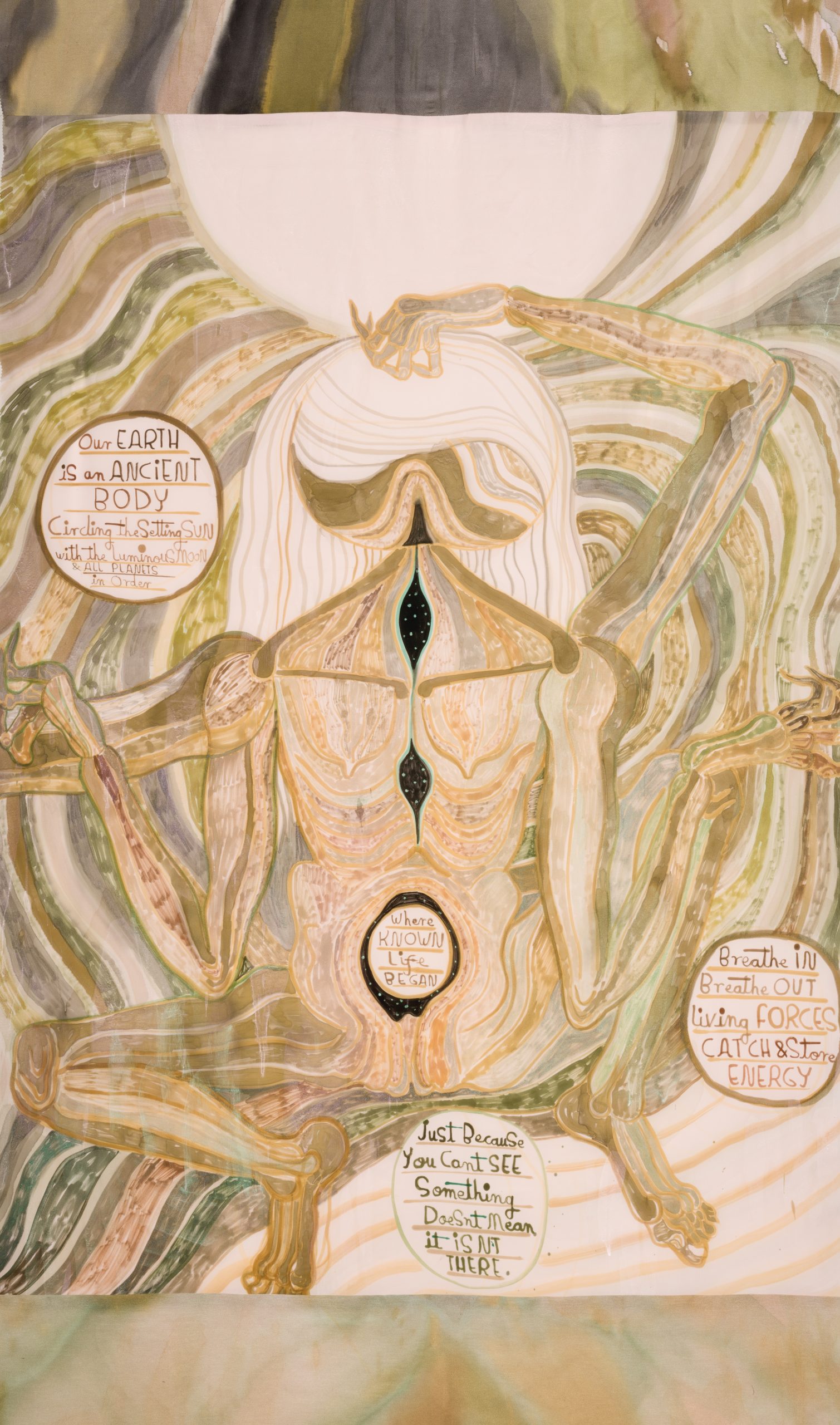

Even in Emma Talbot’s monumental new silk paintings at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, the breath is referenced. While The Age / L’Età depicts a woman tackling the Herculean modern-day trials of the climate crisis, one of Talbot’s texts reminds us: “Breathe in, breathe out, living forces catch and store energy”.

Across these myriad cultural contexts, the rather throwaway line “remember to breathe” has never resonated so deeply.

Victoria Woodcock is a freelance journalist and a contributing editor on the Financial Times’ HTSI