Annie Ernaux’s Exteriors (1996) is an invocation of looking outwards, and as I imagine anyone familiar with the London Underground during commuter hours would easily tell you, this is a somewhat rare task for the city dweller. In fact, it is a somewhat rare task for many these days– the significance we place on self-awareness, self-analysis and self-branding (a la self-care) is not without reason, but it is a double-edged sword, sharing its seat with narcissism. Identity itself can become a sword itself: one to be branded by others rather than inextricable from them. Exteriors opens with a Rousseau quote: “our true self is not entirely within us”.

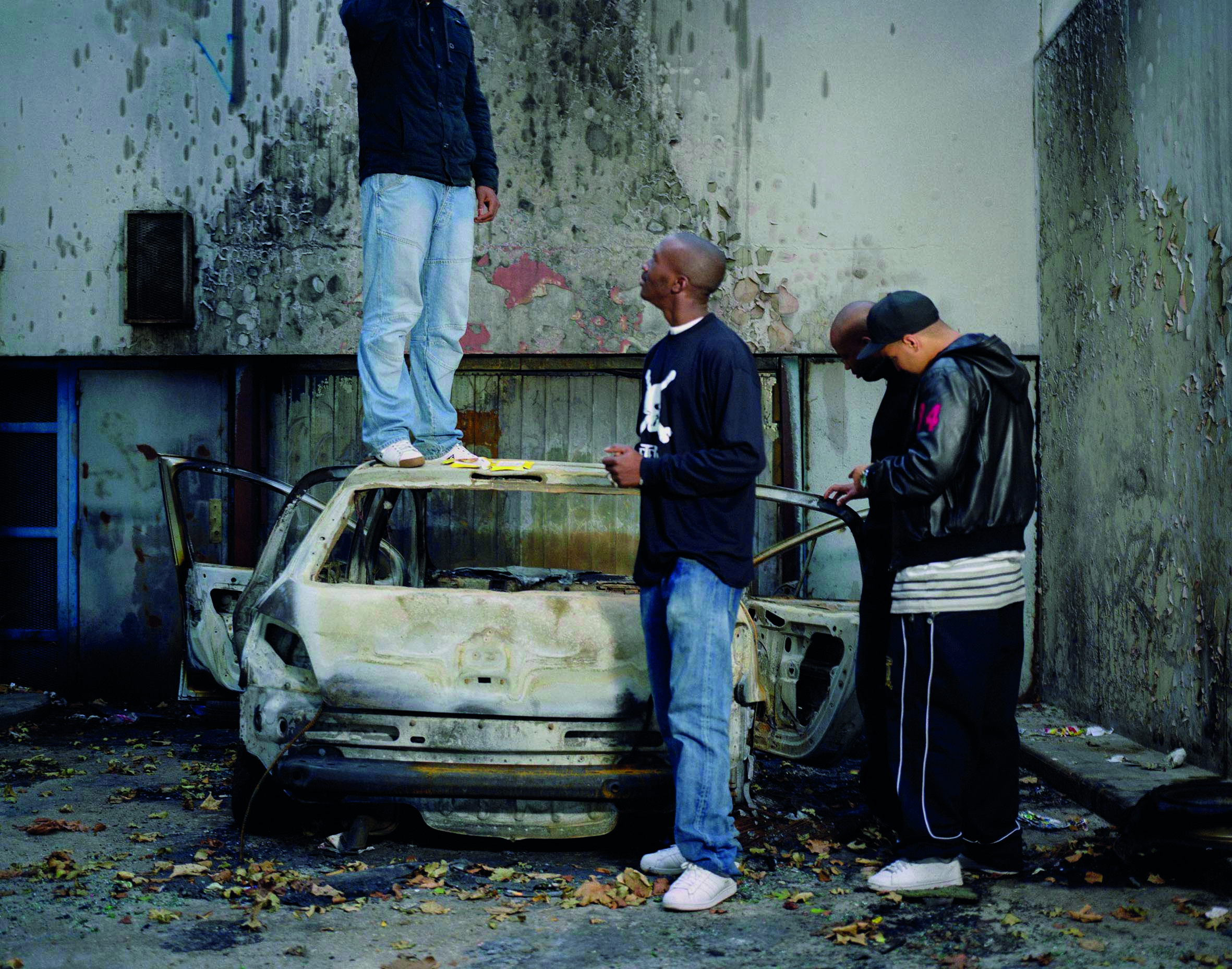

In its eponymous exhibition at the MEP Paris, curated by Lou Stoppard, fragments of Exteriors are placed alongside the work of multigenerational street photographers. The show was conceived shortly after the coronavirus pandemic, during which public space had become something rather uncharacteristic: private, weighted with privilege and the shadow of death. Despite the texts’ origins, as recorded moments from suburban Paris during the years of 1985 to 1992, their observations are no less pertinent to contemporary existence. Ernaux –who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2021– seeks to record her subjects “as through the eyes of a photographer”. The results are, like the images chosen by Stoppard to accompany them, detached but lyrical; poems in prose and visual form.

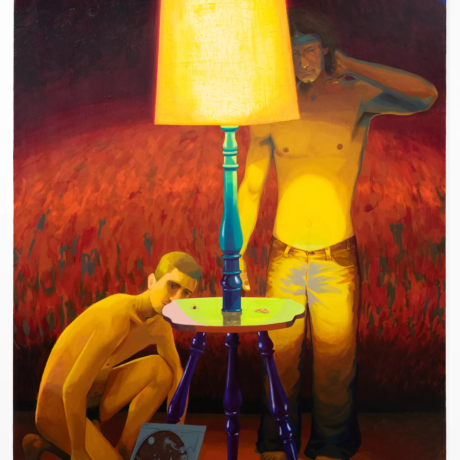

Both mediums are presented as equal partners in a deliberate curatorial attempt aimed at evoking contemplation of our approach to text and imagery, as well as the (non–)realities conveyed by them. The written fragments are presented in small text on blank, luminescent white pages, meaning you’re required to get close up to read them (at least I do, in my short-sightedness), and evoking an intimately conspiratorial feeling, like whispering a secret. One reads: “Only screwing matters, and, on a darker part of the wall, in red, there are no inferior men.” A wall nearby shows a Henry Wessel image: a woman pulling her skirt up, revealing a leg on which a large bruise is blossoming. Even in black and white, the scene is visceral, a voyeuristic depiction of sex and violence.

Other notable names adorn the photographs’ captions: Claude Dityvon, Bernard Pierre Wolff, and Dolorès Marat, to name a few. Marat’s hazy, somewhat Lynchian depictions of everyday scenarios are my favourites. In Le café des Halles (1997), knickers and thighs are reflected in the blood-hued flusher of a public toilet, a setting in perpetual, awful limbo between communal and private (the proverbial lunchroom for losers). The image is that of a quotidian moment loaded with narrative potential, but the words surrounding these evocative scenes don’t describe them, instead existing in dialogue with them. They are united in their approach to creation: to convey reality without compromise.

What it means to capture reality is, as Stoppard tells me, “in some ways a very tired debate” in photography since people generally understand that a photograph is never truly real. Language further complicates things with the ruses of ‘fiction/non-fiction’, and the exclusivity of snooty intellectualism. Perhaps the objective recording of reality is a slightly utopian task, particularly nowadays, as implicated as it is with image currency, digital manipulation and artificial intelligence, as well as our own, increasingly internet-based, existence.

The internet rewards spectacle. It values that which claws a few seconds of attention from our numb, media-saturated stupor or nightly doom-scrolls. I imagine writing my own daily Exteriors: its train carriages would be populated with endless bobbing thumbs, its overheard conversations drowned out by the tap-tap-tapping of the Apple keyboard. What would this say about us? “The feelings and thoughts inspired by places and objects are distinct from their cultural content”, Ernaux writes, “thus a supermarket can provide just as much meaning and human truth as a concert hall”.

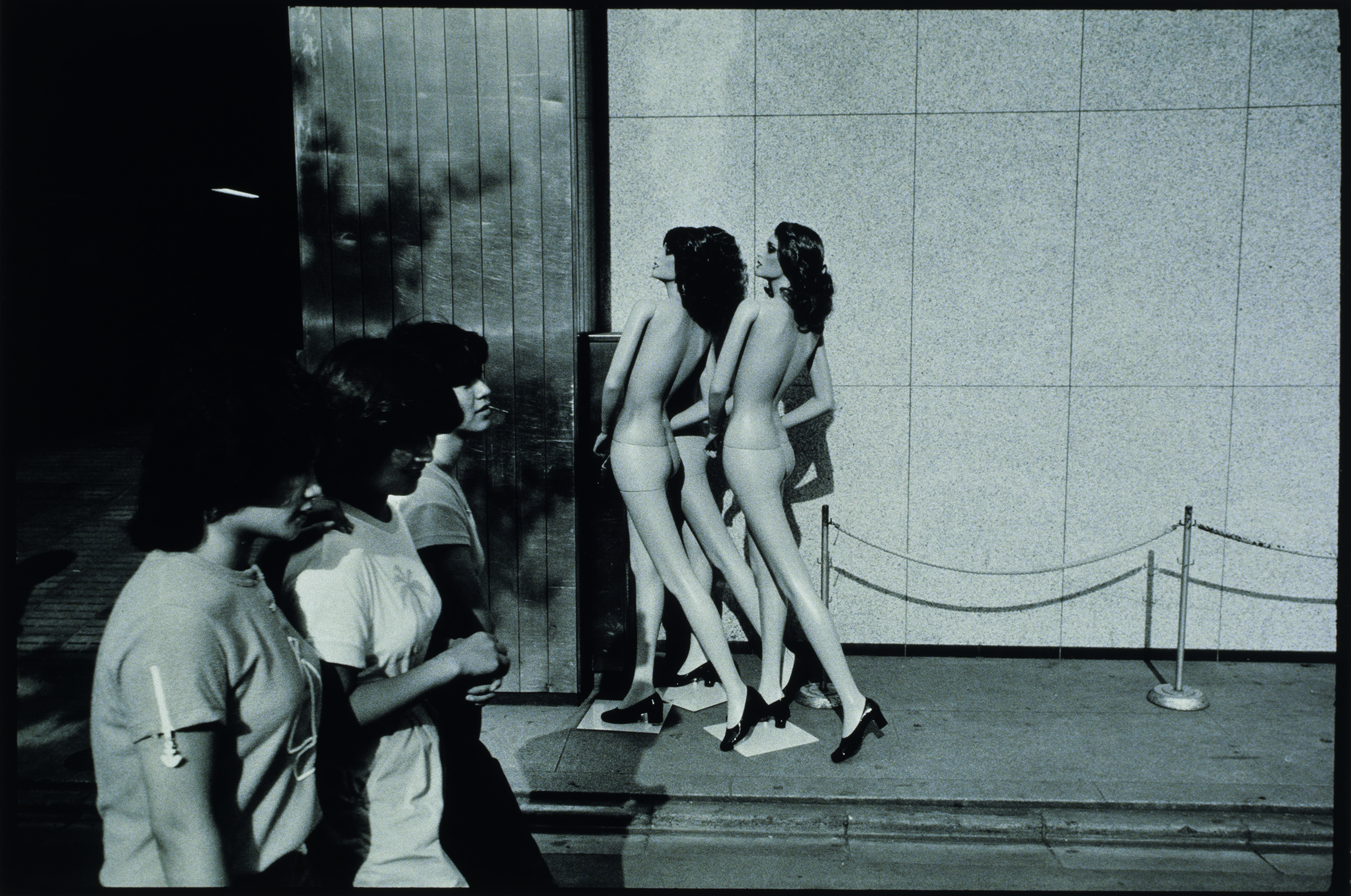

For Ernaux, public transport (in particular Paris’s suburban commuter trains, the RER) has always been ripe with meaning and human truth; illuminations of both systemic and individual attitudes to gender, race, class and age.. One of the images on display at the MEP is Hiro’s Shinjuku Station, Tokyo, Japan (1962), a claustrophobic, near-life-size depiction of a crammed subway carriage. At its far end, a young woman is pressed to the window, an expression of quiet exasperation on her face. The men surrounding her, whose shoulders her forehead does not even nearly reach, show no signs of concern. I think of the discomfort of being shoved up against strangers, the brush of a man’s hand against a girl’s thigh or the bitter smell of someone’s morning coffee on their breath. “I believe that desire, frustration and social and cultural inequality are reflected in the way we examine the contents of our shopping trolley or in the words we use to order a cut of beef or to pay tribute to a painting,” Ernaux says. They are present “in anything that appears to be unimportant and meaningless simply because it is familiar or ordinary.”

My own first encounter with Ernaux’s work was Simple Passion (1993), in which the author records a two-year affair with a married man in her characteristically stark but vulnerable prose. I’d recently read Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick (1997), and the parallels between the two struck me. Both books are accounts of lives, or periods of lives, lived completely for another; they are complex truths. In confession, obsession; sickness, both Ernaux and Kraus elicit liberation. Ernaux writes, as Stoppard describes, in an “unsentimental but probing way, about her own emotions, but also topics like abortion, death, love and desire.” She cuts to the chase and tells you: you’re a woman, and you’re enough.

Simple Passion is one extreme in the subjective/ objective spectrum of Ernaux’s writing, Exteriors being the other, but they are united in their concern for interpersonal relationships. Exteriors has perhaps been overlooked within Ernaux’s body of work because its starting point is not individual experience, unlike that of so many contemporary narratives. Despite art history’s upending of the figure, the majority of (fictional) literature remains rooted in the individual moral adventure. Exteriors’ content is not comprised of other people but transformed by them.

I finish writing this text on the train, accompanied only by cheap red wine and the silence of strangers, of whom I know little and who know little of me. However, it is in these fleeting encounters that I find myself, my attitudes, perceptions, and prejudices. Other people are both portals to empathy and mirrors to identity. No more staring at the cracks in the pavement! Another excerpt: “It is other people – anonymous figures, glimpsed in the Metro or in waiting rooms – who revive our memory and reveal our true selves through the interest, the anger or the shame that they send rippling through us.”

Written by Ella Slater

Exteriors – Annie Ernaux & Photography is on view at MEP until 28 May 2024.

more info