After a brief meeting with the arrestingly warm artist at Rhythms and Reflections

After a brief meeting with the arrestingly warm artist at Rhythms and Reflections

, her solo exhibition at Waddington Custot gallery in London in November 2016, I have crossed the Channel—Brexit not withstanding—to visit Fabienne Verdier’s two studio spaces about an hour’s drive outside Paris.

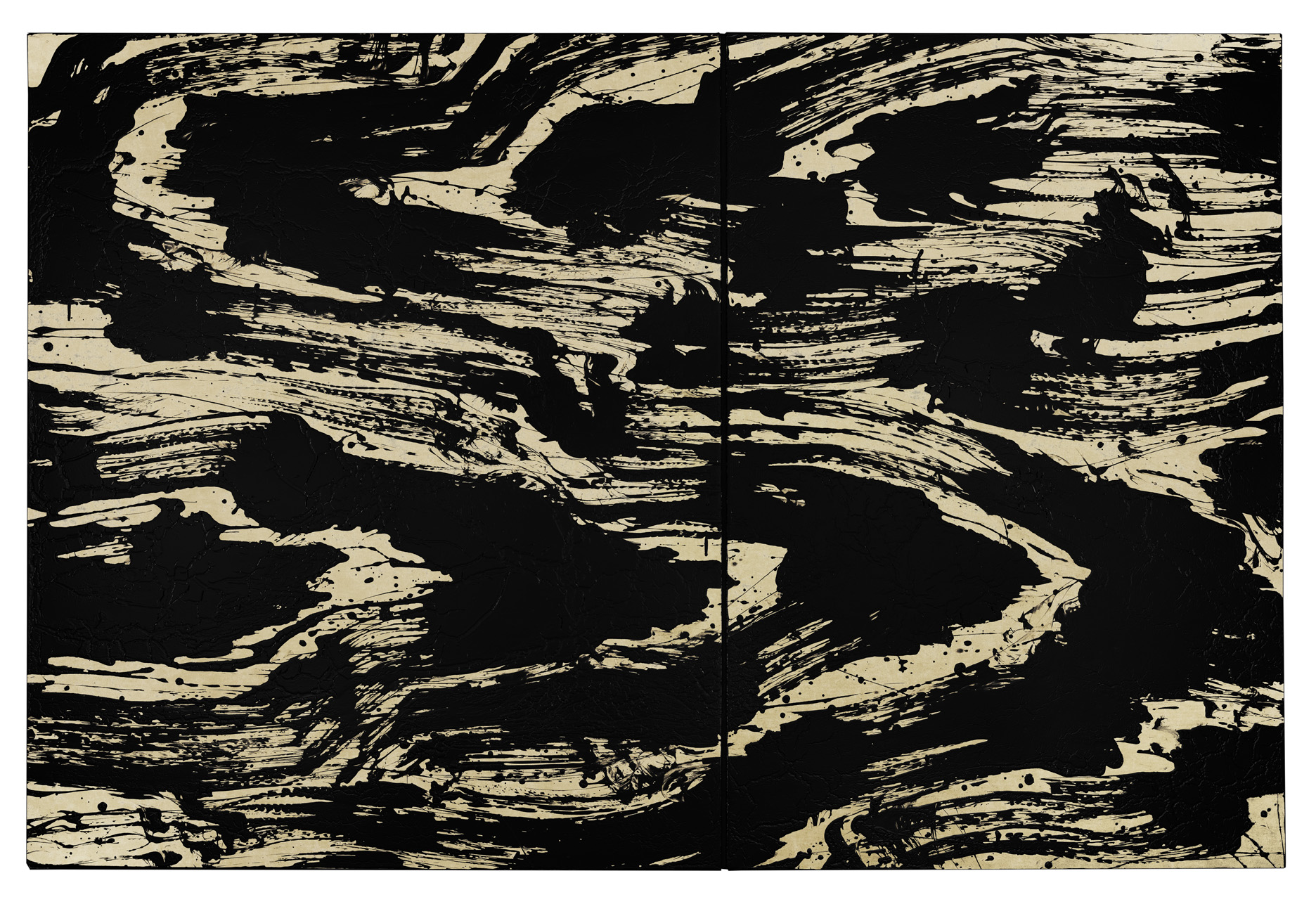

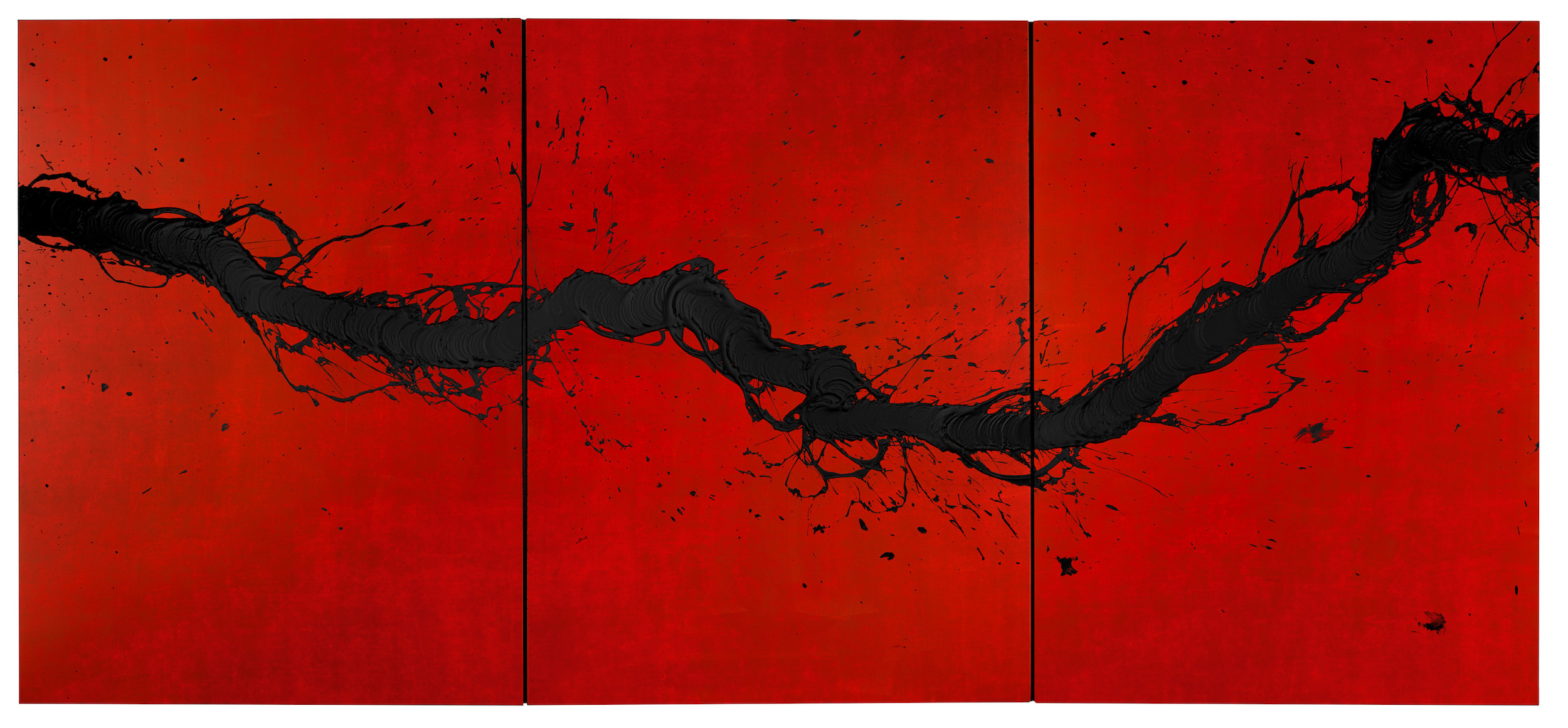

Verdier’s works are large-scale and impactful. She paints from above with a variety of large and often unconventional tools including a brush made from twelve horsetails and a funnel-type contraption that delivers paint directly onto the canvas. In positioning the canvas on the floor, gravity pulls the paint directly towards it. It’s a force that is evident in the weight of the painted line.

Her paintings are generally made in two stages. First, a single-colour background is created and meticulously worked into to give it a tremendous amount of depth. Against this, she then creates single or multiple lines with her enormous alt-brushes. The lines are created with minimal sweeps, perhaps a single continuous movement, from which smaller, vein-like marks often track away. Watching the artist at work, on film, I was surprised by how quickly she moves when applying her line.

“It’s between control and uncontrol,” she tells me. “It’s the great mystery of painting. If you completely control it, the mystery could get lost in the paint. If you don’t control it at all, nothing happens. It is death. But when you are there with the brush there’s an intuitive experience, where suddenly your brain and your nervous system understand that something has happened. I always play with this, as if I’m waiting for the accident.”

This forms the very dynamic part of the artist’s practice, for which her first studio space, sitting in an industrial complex, seems ideally suited. This morning, three white-suited, masked assistants are testing finishes in a glass-doored booth, conjuring visions of HBO’s Breaking Bad. One of Verdier’s large, bicycle-handled brushes hangs from a mobile metal beam at least twice human-height overhead, red-and black-tinged with paint. There are large canisters full to the brim with painty water, brushes of every size and shape hang from the wall, and sunflower yellow, bright blue and black freshly painted canvases are propped against tables.

The second studio space is calmer, almost Zen, built into the grounds of the cottage the artist shares with her husband and son. It fuses Eastern and Western architecture. In the grassy area between house and studio, little can be heard but a quiet trickle from the perfectly rectangular pond. To one side of the garden is a circle where Verdier burns the works that haven’t quite made it for her.

“I want to learn a lot before and do research and wait for the maturation of the abstract mind to talk with some substance,” the artist says of the many notes and marked books that lie about her black-walled library, stacked floor to ceiling with books, natural forms, skins, fossils and semi-precious stones and notebooks. “But I never want to import that in a figurative way. I like to learn about the history and background of which artist turned around which idea, and how they painted and represented it. How Anish Kapoor turned around the idea of the circle, or a Flemish master of the fifteenth century, or Leonardo da Vinci. This makes the form I have to invent much more vivid, and also I try to see the whole human artistic experience together to enrich the abstract language.”

“The painting sends me what she wants to say. I’ve been waiting for that for thirty years”

It’s easy to find yourself reading natural forms in Verdier’s non-representational work—mountainscapes, branches of trees and clusters of capillaries. For the artist these are all one and the same.

“I am nature, I have all these forms in my brain, in my memory, in my bones, in my blood,” the artist says with characteristic passion. “We have a huge force as human beings. That connection is the most interesting thing in the whole world. We often learn that there is you and the whole. But in fact we are one. It’s a beautiful thing because, despite the huge complexity, there are rules behind it. Painting allowed me to understand all of that.”

Verdier has had a tempestuous relationship with rules throughout her life, throwing off many traditional techniques and expectations, but dedicating herself wholeheartedly to others. “At six my parents divorced. I was the first of five children and it was very difficult for me,” she tells me. “I have a kind of hypersensitivity. On the weekends when we visited my father, I would often go to the museum and suddenly I was in contact with artists like Yves Klein and I felt so well in that kind of art milieu. At that time I said to my father: ‘I want to be a painter.’ He taught me with a traditional easel. He really wanted me to encounter reality through perspective. The thing he wanted, I didn’t see. He said I was a rebel. During all my life after, in art school, it seemed that all traditions were death for me. I wanted to catch the spirit. At that time they said: ‘Maybe only in Asia can you train yourself to have this mastery of spontaneity.’”

Verdier moved to China in 1985, aged twenty-two. She studied at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in Chongqing, and also trained under a Chinese master, Huang Yuan, learning the gruelling processes of spontaneous painting.

“The traditional training [in China] could have broken me forever,” she says. “It was so hard, and so strict and demanding. You have to recognize that you are nothing. At that moment, something, some integrity or some natural spontaneity, and a clear vision of what reality is, appeared. You have to understand that after years and years I am just beginning to have that freedom. You have to paint like you breathe. I learnt how to master spontaneity in one brush stroke and one energy line, and once you transform that one energy line you can suggest every form in the world.”

She doesn’t like to align her Chinese training with her practice too closely now, however, and in many ways it has moved past any specific location or culture. But there is certainly a sense of landscape and the natural world within those lines that makes it difficult to ignore the Eastern influence entirely.

Her process is meditative, but also physically demanding. “I put my whole self into it,” she tells me. “It’s very strange because in one way I forget who I am and what I want to say because I become the subject of my painting. In fact, you are in the non-being attitude but in this non-being ritual, during the painting session, maybe finally you find the deepest state of being you ever knew.

“Is it unconscious or superconscious? I don’t know. You are in hyper concentration and suddenly the tree appears by itself. Because I am in total devotion, I give all my energy. Sometimes doctors tell me my painting sessions are very dangerous. Sometimes I need whisky to recover… But at the same time I am born and reborn again. This revitalizes me enormously. Painting has helped me to survive in this world, perhaps. If I do not paint every day it is difficult for me.”

Of course, the dynamic, physical gesture within the work—the line—is very much in dialogue with the backgrounds; sometimes dramatically contrasted tonally with the powerful lines, at others, created black on black. “For me, it’s the idea that the void is not a void,” she says. “So first I have to create a universe with fluctuations, vibration. If there is no vibrational environment, the form cannot appear. I realized that I couldn’t create that microstructure only with the brushes so I create with mixed techniques, with layers of painting and then some layers of screen printing. I continue with glaze and light like the Flemish masters. After twelve or thirteen layers, some vibration appears.”

Although Verdier’s work has had a lot of formal and conceptual consistency over the past three decades, in the last couple of years she has taken steps in new, experimental directions. The first of these was a substantial project in collaboration with the Juilliard School in New York, where she painted alongside musicians. The results were shown in Rhythms and Reflections. In these works, one line becomes two, three and four. They spread out across the canvases, flowing and rippling like water, forming patterns and repetitions in some places, and moving off into their own tempo in others. It was a demanding journey.

“At the very beginning I decided to read the whole dictionary”

“Over the years I have built a strong aesthetic concept,” she tells me, “but when I encountered the music…What a big mess for me! Great musicians invited me to play with them and they said: ‘You have to play with your other painter’— which is to say, don’t stay in your aesthetic thought, but forget everything and let your brain, heart and body catch the wave. Suddenly there were a lot of new abstract structures: my abstract paintings with my aesthetic abstract construction and the music’s abstract construction also. It didn’t work together. So I had to destroy all the things I thought I had built and I tried to accept this new experience.”

This summer Verdier will be the first visual artist in residence at the sixty-ninth edition of the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, painting to music in live workshops.

Recently, words have also found a way into her practice, as she has created works that formally explore the French dictionary Le Petit Robert. “The great master of lexicography Alain Rey knocked on the door. I told him I was afraid. In my mind I had just music at that moment and he said: ‘Words are music. I am eighty-seven, I have devoted my life to those dictionaries. But now I realize that I created for each word an objective text. We need a poetic view. With your abstract painting you could enrich our experiment in a subjective way.’”

True to form, once she committed, Verdier really committed. “At the very beginning I decided to read the whole dictionary,” she laughs. “Every page. I realized it was impossible. I thought maybe it’s an idea to create a kind of inventory of all the forms I turned around during my thirty years as a painter contemplating the natural world. I decided to create twenty-two paintings. At the beginning I chose one word and it was too simple, there was no creative shock for people to discover something new. So I decided to create couples. When you put two words together you open a new poetic field.”

I view the resulting works in their development stage—bold and energetic, related to word couplings including “labyrinthe, liberté”, “esprit, évasion” and “force, forme”.

It feels as though, after following a very direct and considered path for a long time, Verdier has recently changed tack. “You often have your old patterns disturb you and it’s very difficult for me because I have this great matter in my mind,” she says. “I recognize de Kooning, I recognize Rothko—all the great masters of strong energy and action painting. But I have to find my little path. Recently, really after thirty years of hard work, very hard, you have no idea, something free appeared and it’s not for me to decide: I want to paint this. The painting sends me what she wants to say. I’ve been waiting for that for thirty years. And I can’t explain it. It’s a mystery.”

Studio photography by Benjamin McMahon. Artwork images courtesy the artist and Waddington Custot, London

This feature originally appeared in issue 31

BUY ISSUE 31