Farley Aguilar has long been an avid reader and a film aficionado, but one quote has stayed with him longer than others. It is from Invisible Cities by the Italian writer Italo Calvino. “The inferno of the living is not something that will be,” writes Calvino. “If there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together.”

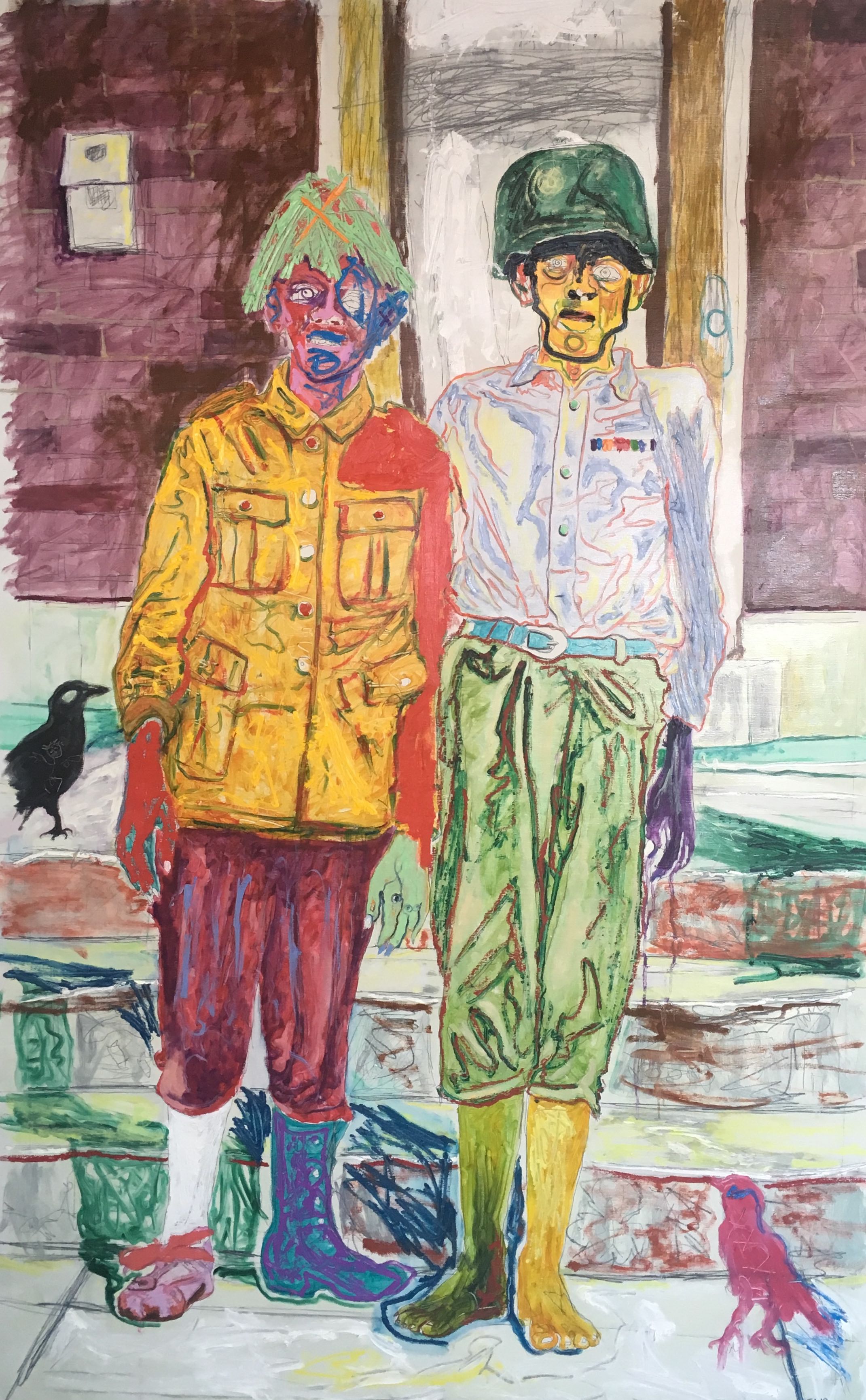

Looking at the self-taught painter’s works, which have been described using various diabolical words and phrases such as “waking nightmare”, “delirious” and “frenzied”, the excerpt rings especially true. Aguilar presents groups, large and small, of apparent lost souls—ghostly, threatening and desolate. On the one hand they are phantoms from another time, doomed to drift forever in a purgatory-like state. On the other they are you and I—individuals in the here and now, each of whom, Aguilar seems to suggest, has a part to play in the collective wretched state of affairs in which we find ourselves.

“It’s interesting how individuals are swept along in a kind of sea of their times,” says Aguilar, on Skype from his home in Miami. “Everyone dresses and thinks alike and performs certain tasks. One thing I am interested in is promoting human agency. The subject has to remember that they do have a say.”

At the heart of Aguilar’s work is an interest in and scepticism of the creation of power structures, a fascination with the dynamism of the group in society, and a preoccupation with human fallibility. Themes that weave in and out of his paintings include inequality and its genesis and effects, the impact of capitalism’s relentless march, and the threat of populism. His paintings could be read as depictions of a broken society tearing itself apart.

For his latest collection of works, recently on show at London’s Edel Assanti in Farley Aguilar – Contraiety, the artist drew from Lewis Hine’s child labour images and other archival photographs that feature breaker boys (young coal mine workers) and female operatives who were employed in the garment and electrical industries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which contends that inequality is not accidental but rather a feature of capitalism, was a key source of inspiration for this most recent work. “I found that book fascinating because it’s a longitudinal study on the economics of societies,” says Aguilar. “It was eye opening to see how societies have [evolved]. It’s not a law of nature.”

“One thing I am interested in is promoting human agency. The subject has to remember that they do have a say”

Sometimes attacking the canvas with paint when he feels a strong emotion towards a character, Aguilar uses photos as “jumping off points” and occasionally scratches in fragments of text and found scrawled drawings using graphite to point to “the dark things in society” and build psychological profiles of his menacing, vacant characters.

“The graphite is interesting because it is traditionally not seen in the finished painting,” he says. “It’s almost like the skeleton or the ghost of the painting. In some of my paintings I almost make the graphite explicit—you can see it on top. As for putting in text or drawings, I look up little pencil drawings of planes and bombs and fires by children who have been exposed to war, and also find images of toilet drawings that are disturbing, explicit or hateful. It’s an anonymous way for society to rid itself of things it can’t say out loud. I find those fascinating and use them a lot in my paintings.”

Aguilar never went to art school and came late to painting, in his twenties, although he dabbled with paint as a child. There is a lot of back and forth in the way he builds up each painting, he says. “I react intensely to what I think is going on in the image and then I’ll back away from that intensity, look, and try to think about what took place. So it’s a back and forth between a calm, more rational way of dealing with the image and an explosion that is more psychological and emotional.”

Using black and white photos allows more room to work with colour, Aguilar says, adding that he researches widely and may look at many photos before one resonates with him. “I’ll look up a certain subject like a boy holding a flag or a group of people outside of a school or a factory,” he says. “A lot won’t work but there will be one or two that will speak to me and I can work with them and use them as a starting point.”

“I started off with images of children dressed up at Halloween parties or kids walking around—just mundane snapshots, images that weren’t meant for high art or to be beautiful,” he continues. “I’ve taken them out of that context to re-evaluate the image or so the viewer can re-evaluate themselves.”

“I hope the fact you have these groups of people from the past staring [engenders] feelings of empathy”

The symbol “X” often features in his paintings, as do swirls, both of which are used very deliberately. “The ‘X’ is fascinating because in cartoons it means a character is dead, and an ‘X’ was used in the past by people who couldn’t read to sign off a contract. ‘X’ is also a variable that’s unknown, so there’s a lot of weight that can be attached to it. I always see a swirl as [representative of] indoctrination, like in the Dr. Mabuse movies by Fritz Lang

in the early 1930s,” he continues. “That swirling movement is now seen as cheesy but I see it as a powerful symbol of being indoctrinated into a system of one’s own time.”

Children and Flag, 2019. Oil, oil stick, and pencil on linen, 213.4 x 158.8 cm

While Aguilar doesn’t want to tell people what to think or feel, there is an undeniable tension in his work between a society or world that is beyond hope and a sense that all is not lost.

“I’ve just started reading Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit, which is to do with this empowering subjecthood and how you can create a different pattern of seeing things,” he says. “It sounds so didactic and ridiculous. It’s always [up to] the viewer how they relate to things. I hope viewers ask why these people are staring, why they are in this situation, why they are presented to me in this way. I hope the fact you have these groups of people from the past staring [engenders] feelings of empathy, or makes the individual feel as though they can do something or be awakened.”