It’s not just the pictures we take, or the pictures we share, that have currency within our increasingly visual culture. Our physical appearance is more “flattened” into a 2D image than it has been at any point in history, and the tools for editing and refining that image have never been more accessible. Psychologists are even beginning to define a new condition: “selfie dysmorphia’”. At the same time, cosmetic surgery is becoming more culturally visible, with many surgeons actively recruiting through “before and after” images on social media, bringing the blood and guts of the process into our visual consciousness even as the pouty, symmetrical, homogenous results fill our feeds.

Cosmetic enhancement is simple, it’s relatively cheap, and everyone’s doing it. It’s practically self-care in a world where physical appearance can drastically affect mental health. But it’s also labour; you’re expending time, energy, and resources in pursuit of a vaguely defined and subjective goal. Both the goal and the labour are deeply entangled in vision, aesthetics and the culture of images, so where better to turn for insight than art? Sure enough, many contemporary artworks engage with the new reality of plastic surgery as part of a “self-care” routine, continuing the age-old investigation into the paradoxes and uncertainties that surround labour in pursuit of beauty.

Kate Cooper’s video pieces often carry the sense of a draining struggle against powerful and visceral inevitability. In one, an animated woman in athleisure drags herself staggeringly along a treadmill that just won’t stop running in the other direction. In one, jaws strain against a violent orthodontic device, baring perfect teeth in a contorted grimace. In another, a face with the “uncanny valley” quality common to all digital renderings of human beings is slowly covered with blood. It’s a visual almost impossible not to associate with “vampire facial”—a skincare procedure in which your own blood is extracted and the plasma re-injected into your face, for shining, death-defying results. Cooper’s videos have an edge of anti-decay desperation, with rotting disembodied zombie-hands, anxious breathing and stress-cleaning all leaving a powerful sense of the toll wellness and aesthetic labour can take on us—especially, but by no means exclusively, on women.

Art has had an ambivalent relationship to plastic surgery for decades, in part because art has an ambivalent relationship to beauty. In the nineties, French artist ORLAN underwent dozens of cosmetic procedures as artworks, documenting her efforts to create a classical self-portrait using her own body as a “modified readymade” in a series of videos and photographs. This transition from the human body as a platonic ideal to the human body as mere matter to be transformed, Pygmalion-like, into something perfect, is echoed in contemporary attitudes to plastic surgery.

“Art has had an ambivalent relationship to plastic surgery for decades, in part because art has an ambivalent relationship to beauty”

Today, that attitude to flesh has been married with the aspirational language of wellness and self-actualisation. There’s a kind of prestige associated with having taken steps towards becoming the version of yourself you want to see in the world. Amalia Ulman’s controversial Instagram artwork Excellences and Perfections (2014), which involved her digital “influencer” persona having a (fake) boob-job, explored this added performative dimension. The visibility of the blood and bandages were as much a part of the visual story as the classic before and after, or the old-fashioned discretion.

There are, of course, less extreme forms of aesthetic labour. Perhaps the most common is simply the use of digital filters on our own selfies to alter or enhance our features, from surreal puppy ears and anime eyes to the subtle hyper-control of “FaceTune”. These are tools available for free to all, which don’t require a general anaesthetic or leave scars. These apps take changing your physical appearance beyond simply fulfilling your social obligation to be beautiful and ageless, and turn it into a form of creative expression. They allow people to mix, match and modify their gene-given “readymade” to their hearts’ content.

Cindy Sherman, whose decades long practice of turning herself into an image makes her uniquely well placed to reflect the current reality, recently created an Instagram account packed with wildly warped selfies, run through what looks like dozens of editing apps, filters, and other digital magic mirrors. Sherman hasn’t commented on these selfies at all but they represent a clear, if ambivalent, engagement with the possibilities and pitfalls of creating and expressing yourself though personal appearance. Sherman’s selfies are warped to the point of melting, and her ageing face grins through sparkles and flower crowns almost ghoulishly. At the same time they look like lots of fun, and there’s a humour and an honesty there that reflects the democratic “every face gets a platform” quality of social media.

“These apps take changing your physical appearance beyond simply fulfilling your social obligation to be beautiful and ageless”

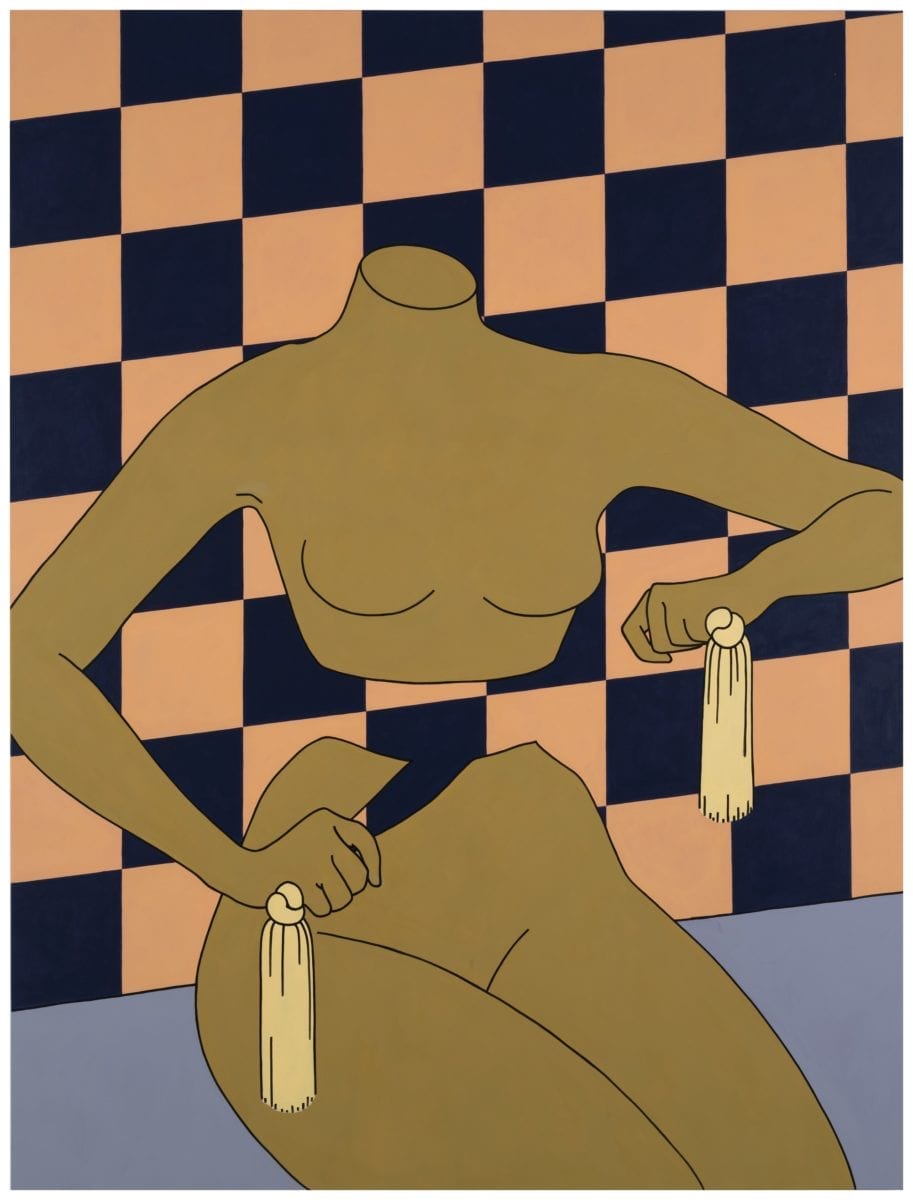

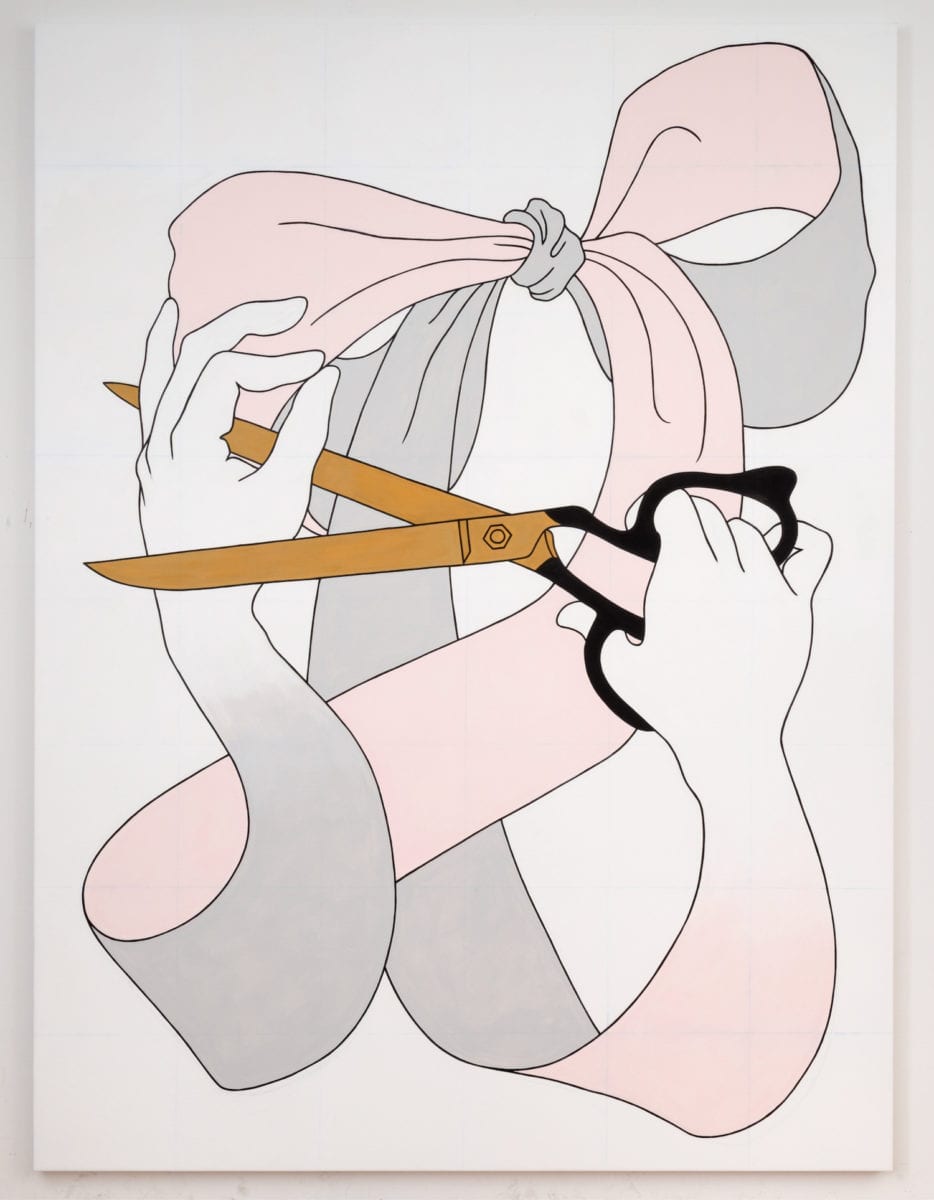

Caitlin Keogh’s surreal, symbolism-laden paintings often evoke the exhausting tension of twisting yourself in knots, carving yourself out, and stitching the results together into something that still ends up feeling disembodied. Floating hands weave tasselled ropes through perforated, headless torsos or wield paintbrushes, surrounded by thorny plants, soft organs, fungi, arms and armour. Her colours, usually bright and clean, are punctuated by muddy khakis and dark greys—the colours of mould and decay. The tension between labour and entropy, as embodied in the female body, is very present in Keogh’s works.

- Caitlin Keogh, Interiors, 2016. Courtesy the artist, The Approach, London, and Bortolami Gallery, New York. Photography © John Berens Photography

- The Modiste, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Bortolami, New York

The pressure to perform aesthetic labour, either going under the knife or turning a digital scalpel on yourself, has increased beyond even the dreams of the man who has more ghostly fingers in today’s cultural pie than any other twentieth-century artist. Andy Warhol one famously said, of the denizens of Hollywood, “They’re so beautiful. Everything’s plastic, but I love plastic. I want to be plastic.” His brazen admiration was shocking at the time. Today, when cosmetic surgery is an open secret (if it’s secret at all), his honesty is much easier to digest, and even relatably frank. An early print titled Before and After I (1961) shows a hooked nose transformed into the perfect seventies ski-slope, and the artist himself underwent a botched nose-job to relieve an insecurity baldly addressed in an early polaroid, over which the artist scribbled a speculative lower hairline and a slimmed down nasal profile.

“The pressure to perform aesthetic labour, either going under the knife or turning a digital scalpel on yourself, has increased”

In later life Warhol became obsessed with bodybuilding, another activity which has moved from a cultural niche into the mainstream; which sees the body as clay; broadcasts images of its process as widely as its results; and which leads many to surgical enhancement when exercise alone cannot provide the required results. Cooper’s animations shows a woman in a sweaty, inflatable plastic muscle-suit that puffs out or sucks in to her body, inspiring a sympathetic sense of suffocation; of the breathless anxiety that our never-ending battle against entropic decay, failure, and ugliness inspires. Historically, art and artists have frontline experience in that struggle, and so there’s a matter-of-factness in much of the work that engages these themes, which reminds us that for all the indicators that social media might be heightening things, physical perfection is a very old obsession.