Seedy motels, fast food joints and the romantic underbelly of urban life are all synonymous with the warm artificial glow of neon. Since the 1920s, the commercialization of “liquid fire” has seen countless industries quite literally put their name up in lights, and although other more high-tech forms of illumination are now available, no other form appears to equal its allure, particularly for artists.

While fluorescent light served as a pillar of minimalism (immortalized by Dan Flavin), the malleable nature of neon tubing has seen contemporary practitioners continually reinvent the form, using it to interrogate everything from violence and loss, to bodily identity and romance.

Tracey Emin

As the doyenne of the form, Tracey Emin has been creating iconic neon sculptures inscribed in her own handwriting for decades. Her poetic phrases often read like extracts from love letters: “The Kiss Way Beautiful”, “You Touch My Soul” or more mournful texts: “I Know, I Know, I Know”, “She Lay Down beneath The Sea”. These beautiful signs feel particularly evocative when out in public, where people can ascribe their own meaning, as seen in St Pancras station’s “I Want My Time With You”—it is actually made from LEDs, but Emin’s experience with neon aesthetics makes the deviation practically imperceptible—and her ode to Margate in the form of a sign that appears to light up the seaside: “I Will Never Stop Loving You.”

In a recent interview for Issue 38 she explains that she was the one to blaze a new trail for neon as a legitimate art material: “At one point it was a really dying industry, but now it is having something of a renaissance. It’s a beautiful material.”

A Fortnight of Tears, White Cube Bermondsey, until 7 April

Ivàn Navarro

Ivàn Navarro builds a world of illusion through his deft use of neon and mirrors, but his practice is far more than an experiment in aesthetics. The Chilean artist views electric light as an important representation of the Pinochet dictatorship, where the government would often turn off the grid as a form of control, as well as utilizing electricity as a form of torture. Navarro has often used neon to investigate communication, whether it be through echomimetic word play of the visceral response we all have when confronted with different colours. As the artist explains: “We add meaning to things ourselves and that’s how my work generates different opinions.”

This Land is Your Land, Navy Pier, until 30 April

Romily Alice Walden

The internet went wild when Romily Alice Walden first presented her series of neon portraits. These beautiful sculptures celebrate a variety of female bodies based on anonymously donated selfies, which are the antithesis of the Jessica Rabbit proportions favoured by the historical home of neon—strip clubs and seedy bars. Since then she has continued to use the medium to interrogate issues of gender, sexuality and ableism, utilizing figurative forms as well as abstraction. In her installation, My Body Is The House That I Live In she examines the culture of “wellness” through the lens of her experiences as a disabled artist.

My Body Is The House That I Live In, SOHO20 Gallery, until 8 March

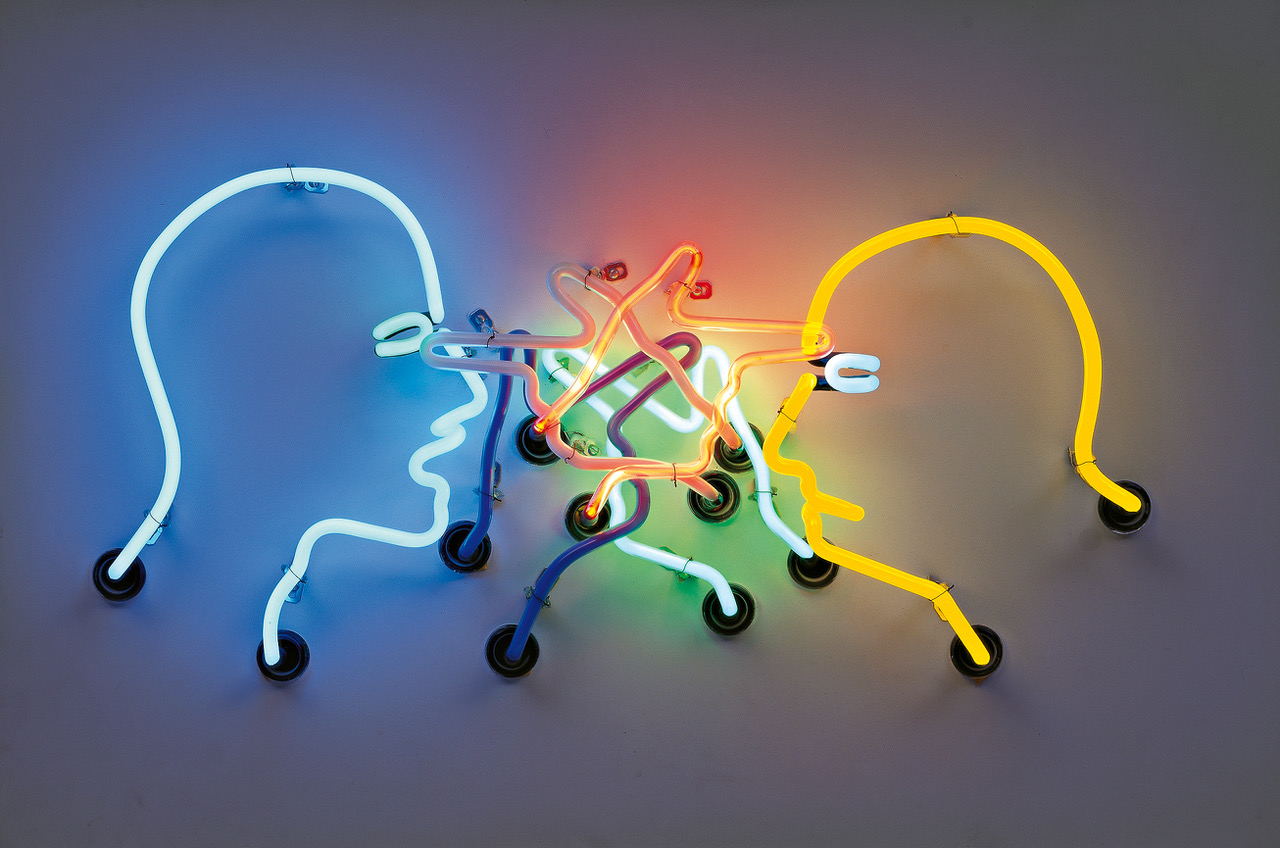

Bruce Nauman

Multimedia artist Bruce Nauman is known for his wordplay, often creating canny neon sculptures that flicker between apocalyptic and comical phrases—“eat/war” and “run from fear/ fun from rear” being a couple of choice examples. Equally, he harnesses the kinetic power of the form to create lurid and absurd images of people having sex or simply conversing. Nauman has worked in every conceivable medium since the 1960s, often using his own body as a “raw material” and continuously experimenting. However, the allure of his neons seem to get the popular vote. A recent ARTIST ROOMS exhibition at Tate Modern was an absolute magnet for audiences (particularly kids) who took delight in reading his salacious texts aloud, or simply basking in the sculptures’ manufactured glow.

Bruce Nauman: Rooms, Bodies, Words, Museo Picasso Málaga, 18 June–1 September

Glenn Ligon

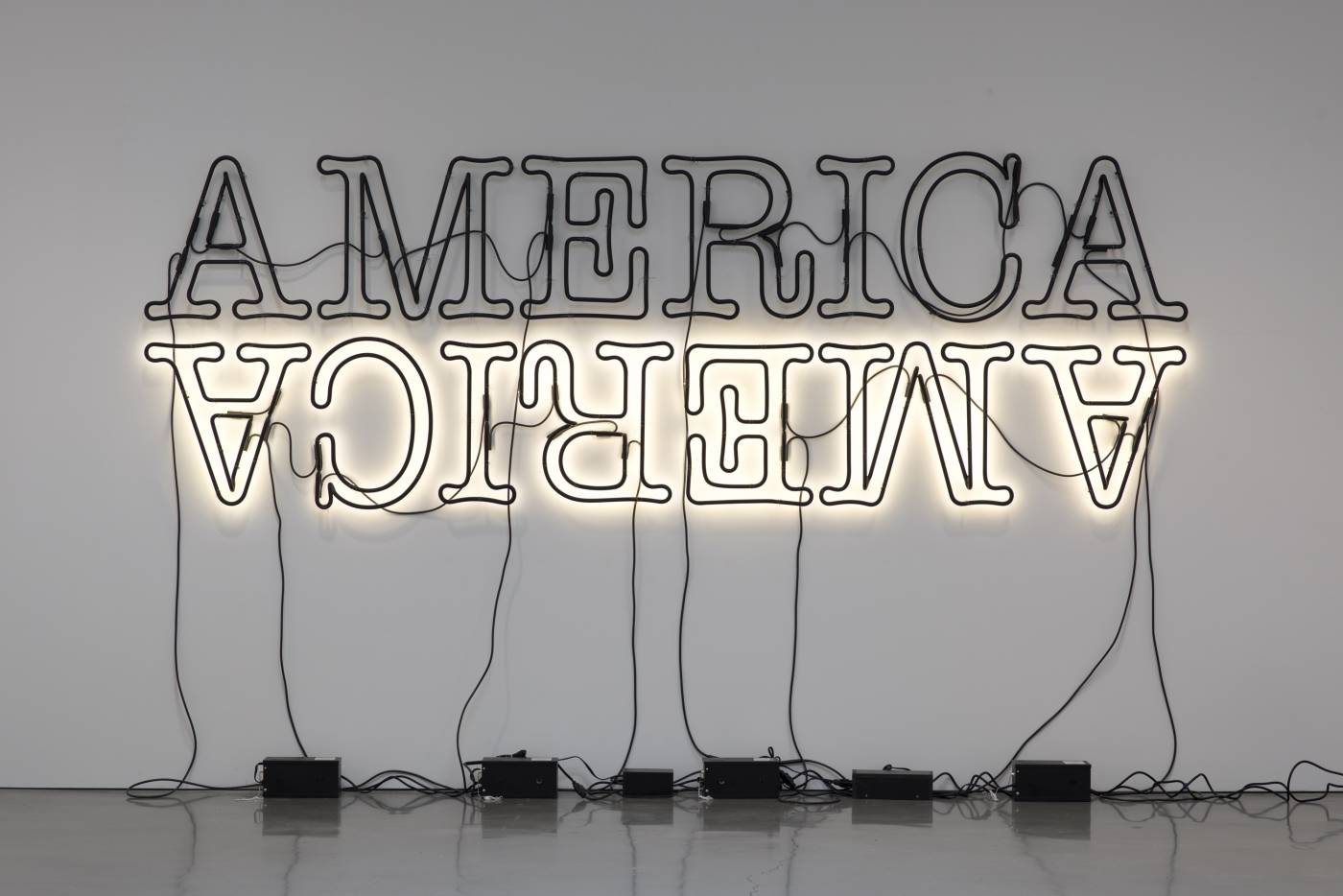

Glenn Ligon examines the power of the written word in his text-based practice, references seminal literary figures such as James Baldwin and Zora Neale Hurston in his interrogation of American identity. His bold neon sculptures consist of a variety of typography that etch out phrases such as “Negro sunshine” (taken from Gertrude Stein’s novel Three Lives) and “Bruise/Blues” (references police brutality) but his most famous works simply spell out “America” in utilitarian letterforms.

He has experimented with the sculptural elements of the word, considering the subversive messaging that can be communicated by presenting the term backwards, or upside down. In some instances, the tubes are also painted black, questioning the paradox of “black light” and alluding to issues of binary politics, which is often exemplified by the illuminated cracks and chips that form on the painted surface.

Glenn Ligon: Selections from the Marciano Foundation, Marciano Foundation, until 5 May

Elephant’s Issue #38 is out now, featuring an interview with Tracey Emin

BUY NOW