One of the best days out to be had in Britain this summer is an excursion to the De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea. Not only is the seafront building a modernist gem resembling an ocean liner with multiple decks and a spiral staircase within a glass cylinder, but the gallery is also hosting an inspired pairing of shows by two British female artists from different generations. In the main gallery, Alison Wilding uses the seascape to activate her bewitching abstract sculptures from four decades in “Right Here and Out There”, while upstairs Florence Peake’s “Rite: On This Pliant Body We Slip Our WOW!” embodies corporal movement through expressive sculptures and a fresco inside a fleshy-pink painted room.

Seventy-year-old Wilding, long overlooked in favour of male peers such as Tony Cragg and Richard Deacon, is on top form. She has wisely chosen not to compete with the mesmerizing coastal scene but to embrace it. Her two-part work Assembly (1991) comprising a steel husk and complex structure of interlinking PVC slats suggests container ships glinting on the horizon, while on the roof terrace, her 2018 floor installation Riptide mimics the rhythm of the waves beyond the railings with ripples of rebar capped with buoy-like polystyrene spheres.

This is a show that rewards time; hidden elements unfold from different perspectives and colours burst from what initially seems a monochromatic display. A tall steel cylinder titled Red Skies (1992) reveals a vertical blood-red sliver like magma in the earth’s crust or dawn seeping across the horizon. Drowned (1993) resembles a monolithic black cone until viewed backlit by the window when murky green fills the interior, evoking the unnerving sense of being enveloped by the sea.

Weightlessness and mass, light and dark, presence and absence, maintain an enigmatic tension in these works. Materials such as neoprene, steel and acrylic are transformed into otherworldly shapes that exude quiet menace. Three black rubber floor sculptures bubble with life beneath their surfaces; from Carpet 1 (1995) rise two pointy horns, which are mirrored in the sharp wings of a black steel sculpture Locust (1983). From a high niche, Floodlight (2001), an ovoid form enclosing a translucent yellow centre, recalls an omniscient eye.

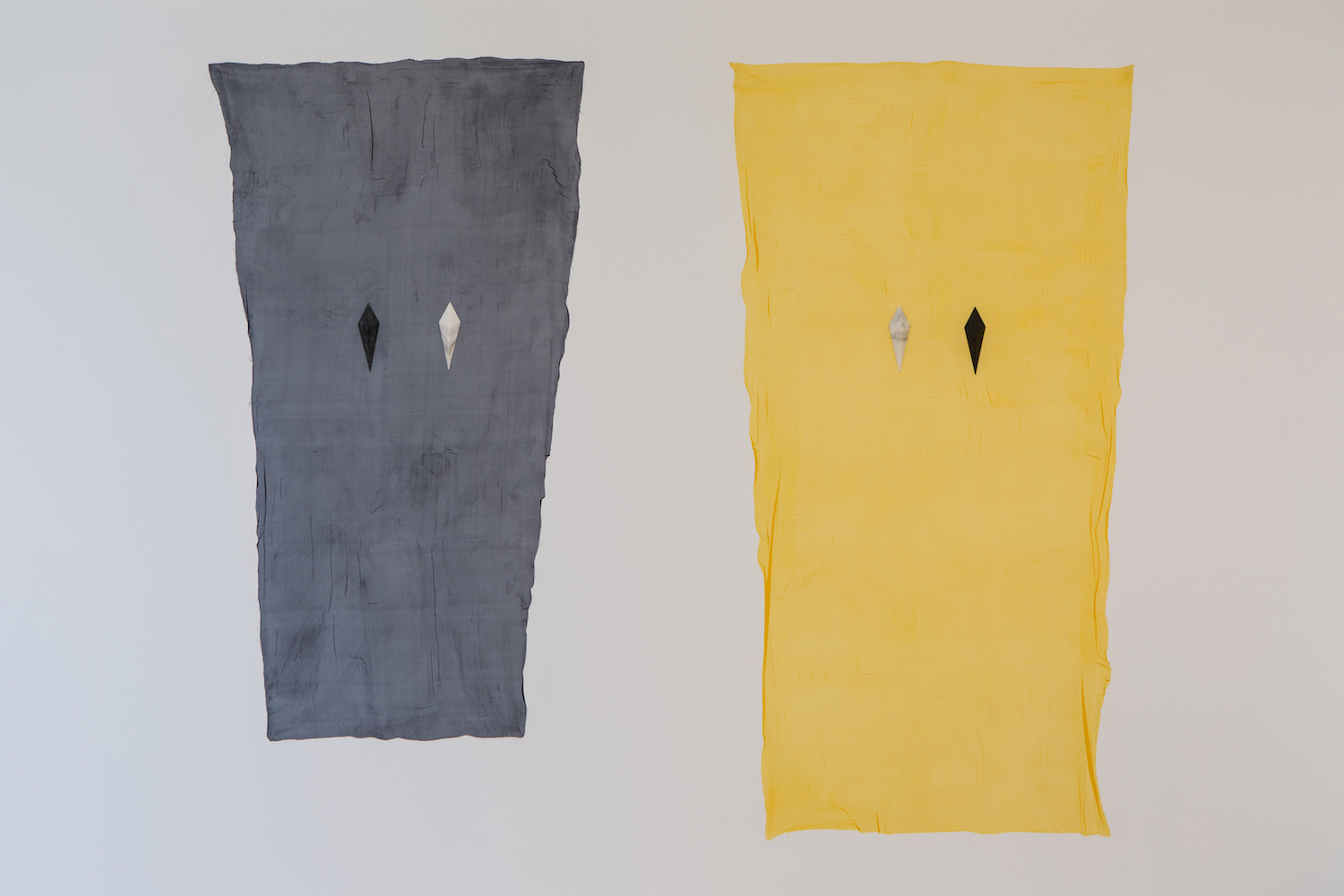

Contrasting with Wilding’s clean lines and precise forms is Peake’s raw, visceral show. Its centrepiece is a sprawling clay sculpture, embedded with hair and human prints, the physical memory of Peake’s performance that opened her exhibition. In Peake’s orgiastic choreography, naked dancers interpreted Igor Stravinsky’s emotive 1913 score The Rite of Spring using six tonnes of wet clay, which pulsated with life, merging with bodies that erupted and writhed in animalistic embrace. Mirroring the elemental landscape of the clay below, the walls are adorned with brutal clay masks and a primal frieze of tumbling bodies enacting the sacrificial rite in earthy tones.

The two shows present a discordant clash of materials, disciplines and styles. Yet the juxtaposition works beautifully. Wilding has known Peake since she was ten, being the daughter of Wilding’s friend Phyllida Barlow, another female artist receiving overdue recognition. I meet Wilding in her Hackney studio, where we are joined by Peake for a lively discussion about their shows.

Elizabeth Fullerton: What determined your concept for the show, Alison?

Alison Wilding: You’re faced with quite a difficult space with De La Warr. It has a low ceiling and is very long, and actually what you really want to do is look out of the window at the sea. The challenge was to make that work with the work. I wanted the work to be seen with the sea in the background, it just doesn’t happen anywhere else.

EF: So the coastal horizon influenced your selection of works?

AW: And by the way the light works with the building. I knew that some quite old pieces of mine would really utilize that light coming in from the side that would light things up in a way top light doesn’t do and artificial light can’t do.

EF: Your sculptures often conceal and reveal simultaneously.

AW: It’s just something that’s there in the work, maybe a bit perverse. A lot of these works are stupid mistakes that in retrospect seem funny. With Drowned, there’s a load of stuff on the inside that I, in my naivety, thought would be revealed when the piece was assembled, such as the gold leaf on those two heavy curved steel parts that hold the acrylic cone [inside] up. There’s no way anyone’s going to see that. And on top holding everything in stasis is a copper hemisphere that’s been specially chromed, but you don’t see that either. Richard Wentworth once said that I made all my work backwards and I think there’s some truth in that.

“I wanted the work to be seen with the sea in the background, it just doesn’t happen anywhere else”

EF: References to nature abound, such as the steel rings around black balloon casts comprising Cuckoo 2 (2015) or your roof deck installation Riptide.

AW: It’s probably always been there. I think it’s a legacy of my dad who was such a keen bird watcher. With Riptide, something in the news alerted me to the word—those guys who were drowned in Camber Sands. I got absolutely obsessed with being able to describe a riptide. It’s such a beautiful word for something that is really quite scary.

EF: What dictates your choice of materials?

AW: It is possible to use anything and probably that comes from when I left the Royal College in 1973 and had absolutely no money. I felt really on my own so I was literally using stuff like brown paper and silk, anything I could find. Being able to turn that into something else was something I knew I had to do. I had to be clever with what little resources I had and that’s stayed with me.

EF: How important is your own hand in your work?

AW: It absolutely is. In every piece of work, however much is made outside the studio, there’s always a point when only I can make a decision. Sometimes there’s a need to make something very small which is just about me being in the studio on my own and that’s actually my favourite thing.

EF: Do you relate your abstract sculptures to the body?

AW: Yes definitely. You’re aware of what your reach is in the studio, why you need a tall person to do particular things. In the eighties I made quite a lot of work that was probably very much about the female. I was interested in thinking about the body in a different kind of way, not figuratively but as a container for an idea or something else. I’m not interested in that now but I was.

EF: That leads into Florence’s work. How did you respond to each others’ exhibitions?

Florence Peake: I like that there’s this contrast, this big splurging mess upstairs and that distinct difference is very liberating. At the same time, I can relate to things in Alison’s work which feels supportive for me. This is probably my first major solo show so it’s quite nerve-wracking and there’s a sense that downstairs there’s something with more weight and experience going on.

AW: But your performance was amazing. It was gobsmackingly brilliant actually. It was a pity that you couldn’t have done it every day. I just loved that chaoticness of it and that’s why what you’re left with after seemed tame in comparison.

FP: It does feel sad it was only performed once. We’re taking it to Site Gallery in Sheffield next February and hope to bring it to London. Each time what gets left in the space will be very different. I find it very difficult sometimes to resolve those romantic notions of performative gesture that leaves a remnant behind. How to remodel the space and still hold that quality of what’s left from the performance so it has its own identity or autonomy away from that moment that happened?

“I like that there’s this contrast, this big splurging mess upstairs and that distinct difference is very liberating”

EF: Do you see affinities between your works?

AW: Nothing tangible but I go with it completely. The idea of clay and being able to manipulate anything is central to what anybody who makes stuff does and Florence has this huge backstory about what she’s doing that isn’t just rolling around in clay. It’s much much bigger than that.

FP: I find your work esoteric and there’s a fantasy I have around it being quite mysterious. There’s something very internal, like the inside of the body so the experience is more like some of the processes that I do with my dancers, not necessarily the end result that’s in the gallery upstairs.

A lot of my teaching is to do with images that get placed inside the body and then moving with them. Some of them are quite stark, things like falling through curved darkness; you build soundscapes with those images and guide your students through. They’re very profound, physical experiences. There’s something about your work that has that.

AW: How did you get into clay?

FP: It’s the bodiliness, its physicality, elasticity and plasticity. All these different qualities very much related to somatic movement practices, where the internal experience and anatomy and physiology are privileged over imitation of movement.

“It’s really exhausting because the amount of physicality is quite demanding. The clay very much choreographs the body”

But you actually have to work the clay a lot for it to become safe because there’s elements of the performance that are quite dangerous. You flood the clay with water and in all this slipping and sliding it gets this momentum. I did Rite in Palais de Tokyo and we didn’t have enough time to work the clay; one of the dancers spun and kicked another and she bit through her lip. We do a three hour rehearsal before the main performance and that’s just working the clay so you understand what it’s doing. It’s really exhausting because the amount of physicality is quite demanding. The clay very much choreographs the body.

EF: What drew you to The Rite of Spring?

FP: I just love this polyrhythmic attack, the sense of being ambushed. I find it very spatial so it feels like being flung off a cliff and then into wide open space and tucked into a cavity. If you’re a dancer/choreographer it feels like it’s off limits to work with if you’re not mega mega famous. I thought one way of dealing with that was to make a sculptural interpretation rather than it just being a dance performance.