I’m not going to lie, mythology makes my head spin. I remember parts here and there, but really I have very little knowledge about who is mother to whom, or which sisters descended from which god. I recently found myself Googling “Iolanthe”, when trying to figure out which of Medusa’s sisters I played in my performing arts A-level, before remembering she is in fact the lead fairy and titular character in the very brilliant 1882 play by comedy opera creators Gilbert and Sullivan. I recognized the names of neither of Medusa’s sisters, which made me wonder if it was in fact another famous goddess whose sibling I played. She was a weak character, and a lot of people died throughout the performance (not in actuality, I do hope, but in the narrative). It wasn’t quite as depressing as our performance of Federico Garcia Lorca’s Blood Wedding, from which I remember almost nothing apart from a lot of wailing, but it was pretty close.

A knowledge of Greek and Roman mythology that is sketchy at best is perfectly sufficient to dive into Phaidon’s mammoth new, coffee-table-worthy book Flying Too Close to the Sun: Myths in Art from Classical to Contemporary, which brings together art from the last 3,500 years and is beautifully made, with a textured orange cover. There is an especially handy selection of family trees at the end of the book, covering different houses and kingdoms. A quick scan of this refreshes my memory; it was, in fact, Antigone’s sister, the feeble Ismene, who I played at school.

Within the book itself, chapters are broken up by theme and story, rather than by the chronology of the art made, which gives it more impact than reading like a timeline, where the content then feels less characterful and more museum-like or illustrative. Besides, mythology is such a vast subject, which has influenced such an enormous group of artists over the years, one would imagine that putting together any sort of coherent and all-encompassing timeline would be a losing game. Instead the chapters bring a variety of stories to colourful life.

It’s great to see pieces of contemporary and historical art sitting alongside each other, where readers can explore the responses of artists from varying time periods in the same space. Take the chapter Flying Too Close to the Sun: Daedalus and Icarus as an example—this section draws together the work of unknown artists from the years BC, with that of Frederic Leighton (1869), Anselm Kiefer (1981) and, of course, Henri Matisse, with his hugely famous Icarus from 1947. In the introduction to the section we read about Daedalus, the creative father of the famously doomed Icarus, as an artist, a man ultimately ruined by his “unchecked imaginative power”. Perhaps an early example of the artistic troubled genius.

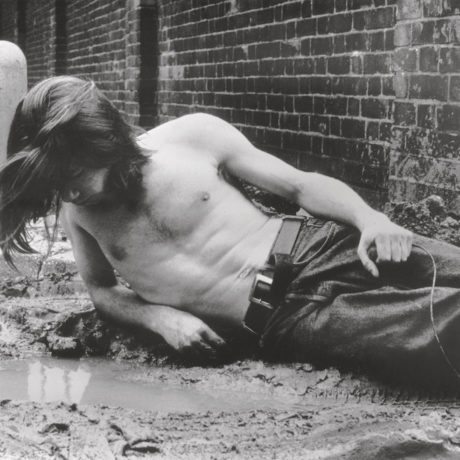

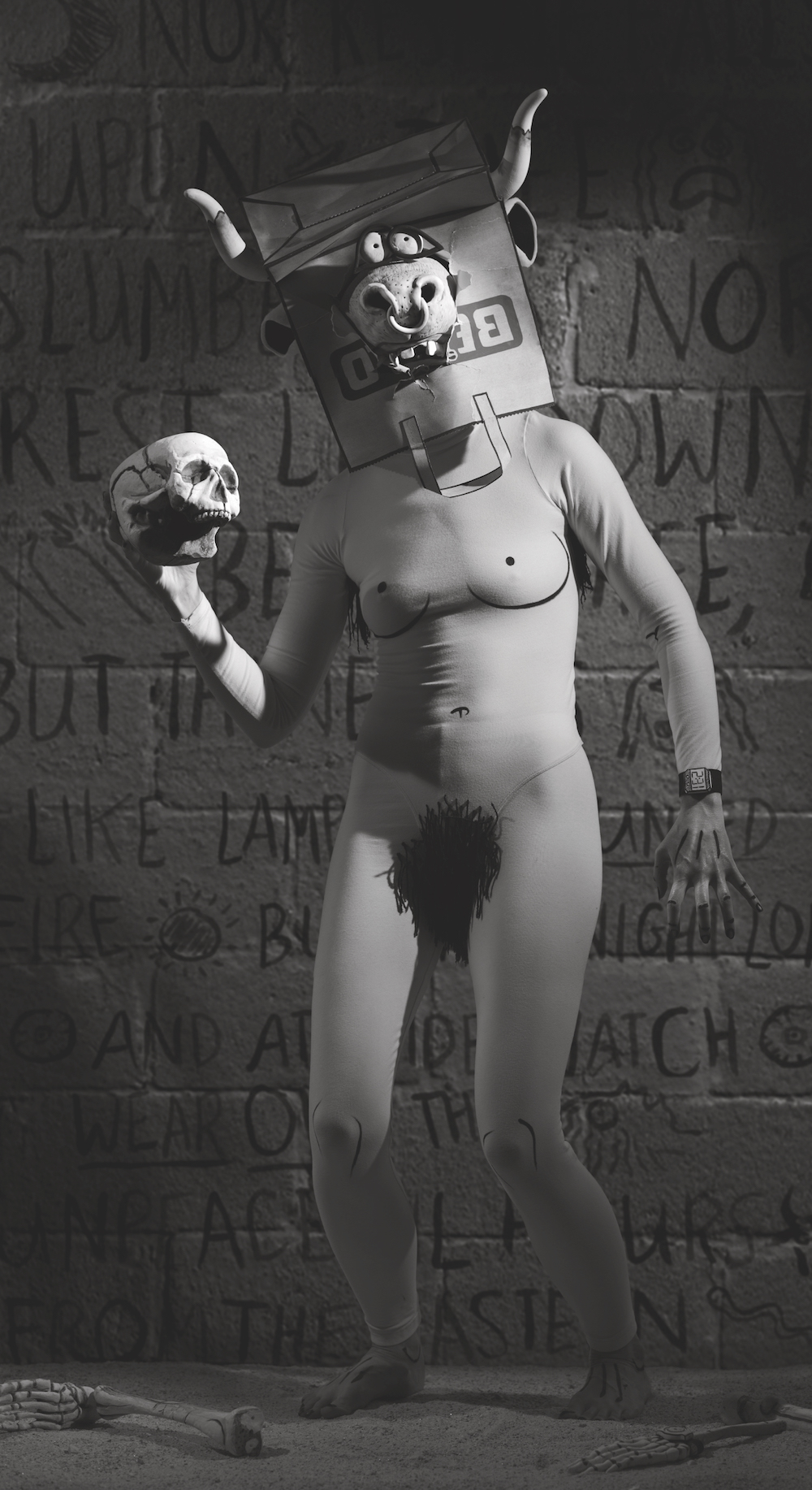

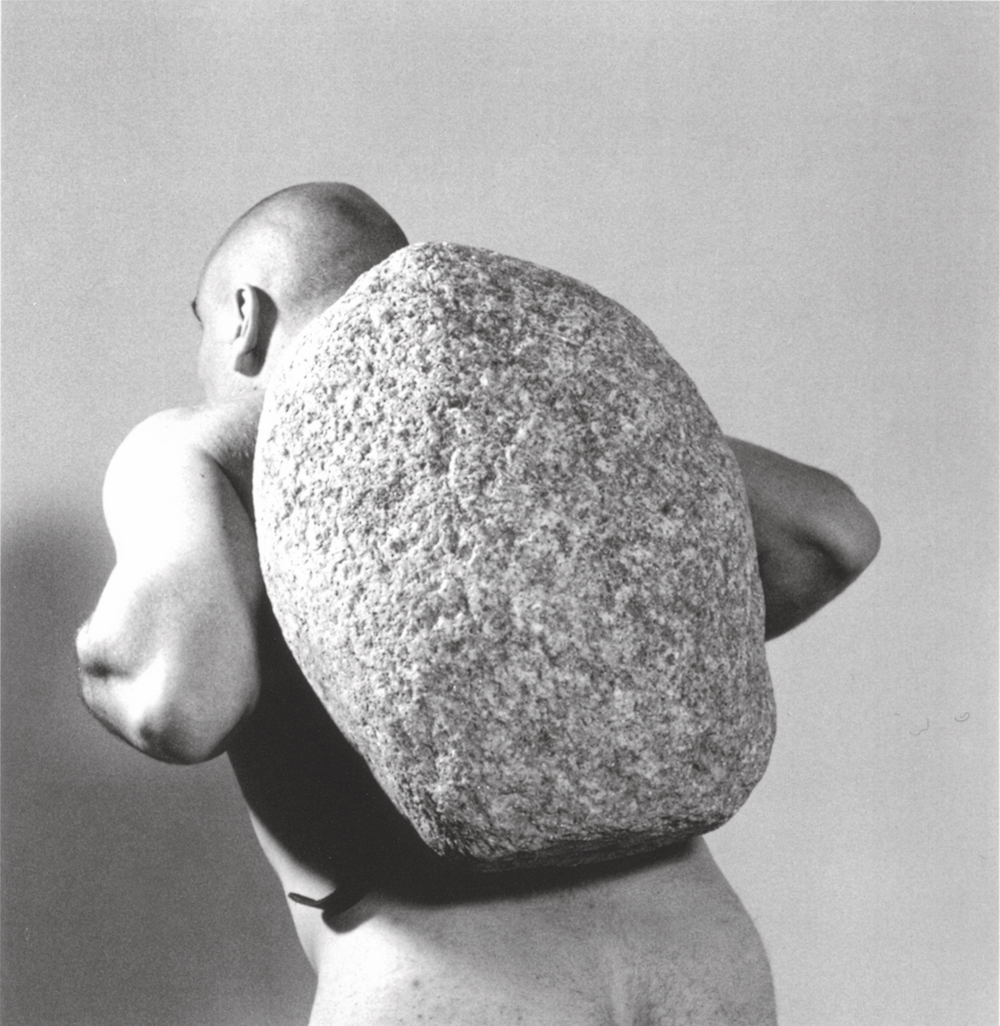

Here we see the visual kapow of the meeting of art and mythology, with the ripped torsos of father and son emphasized in characteristic, lustful glory in the early works; lavish, angel-like wings, sometimes shown on their own as a sign of both hope and human weakness; and the dark onset of tragedy. We also see the changing face of art, where more literal and symbolic imagery gives way to conceptual subtlety, the various myths becoming more of a starting point, or an influence among many, than material for literal illustration (though there are some contemporary works that use the literal to hilarious ends: see the Jaime Pitarch work below, a one-eyed glasses frame, which is fit for a cyclops).

Mythology is heavenly fodder for artists, not only because of the powerful and hugely impactful imagery that has sprung from its stories over the years, but also the lessons and view of humanity that are wrapped up in each of these. Throughout mythology we see human folly and the wins and complications of mortal life addressed again and again—providing fertile ground for artists who often seek to explain or explore the human condition.

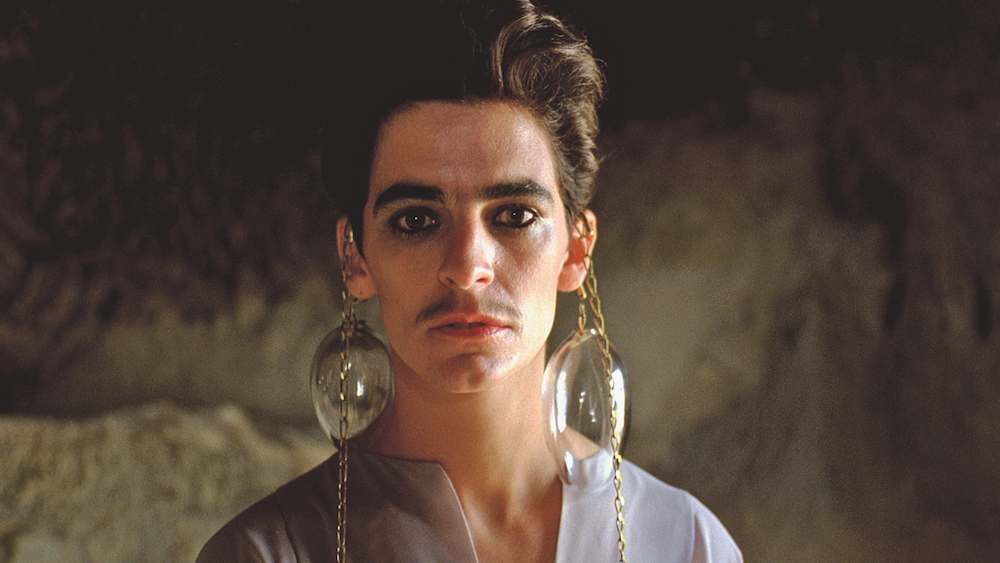

- Ursula Mayer, Medea, 2013. Still from colour film, 12 minutes © and courtesy the artist

- Jaime Pitarch, Cyclops, 2007. Deconstructed and reconstructed eyeglasses, 9 x 7 x 16 cm. Courtesy the artist and Spencer Brownstone Gallery

There’s another thing that makes visual art and mythology so well-suited. Despite the at-times dense nature of both, when both are working well, they can be understood or “got” in a split second. When even a novice like myself sees a vision of Icarus, I immediately think of his over-heated fall from grace—the sticking power of his story means we all understand the basic message of getting ahead of yourself and ultimately trying for too much. Throughout the book there are potent messages, which can be picked up on by the various visual clues left by artists, even when we don’t know the full story.

For those looking for the full story, there is certainly a lot of information to be found here, where every chapter comes with a description of the relevant myth, and every artwork with its own blurb. There is a lot to learn. In essence, however, it feels like a subject that explodes ever outwards, and despite these introductions and the family trees at the back, I finish feeling as though I have only tickled the surface of the enormous story of mythology, and indeed the enormous story of art. You’ll definitely want to take to Google (or further books) to continue your studies or support you while reading Flying Too Close to the Sun—and this level of intrigue is certainly no bad thing for a book to set off.

Flying Too Close to the Sun: Myths in Art from Classical to Contemporary

Out now with Phaidon

BUY NOW