“I got into graphic design through clubbing and concerts,” explains London-based DJ, musician and artist Fred Deakin. That multi-genre, audio-visual meltdown has joyously fuelled Deakin’s catalogue, from his club nights to his work as one half of ambient music duo Lemon Jelly (with Nick Franglen), co-founder of award-winning commercial design studio Airside (with Nat Hunter and Alex Maclean) and currently as professor of interactive digital arts at the University of the Arts in London.

“I got into graphic design through clubbing and concerts,” explains London-based DJ, musician and artist Fred Deakin. That multi-genre, audio-visual meltdown has joyously fuelled Deakin’s catalogue, from his club nights to his work as one half of ambient music duo Lemon Jelly (with Nick Franglen), co-founder of award-winning commercial design studio Airside (with Nat Hunter and Alex Maclean) and currently as professor of interactive digital arts at the University of the Arts in London.

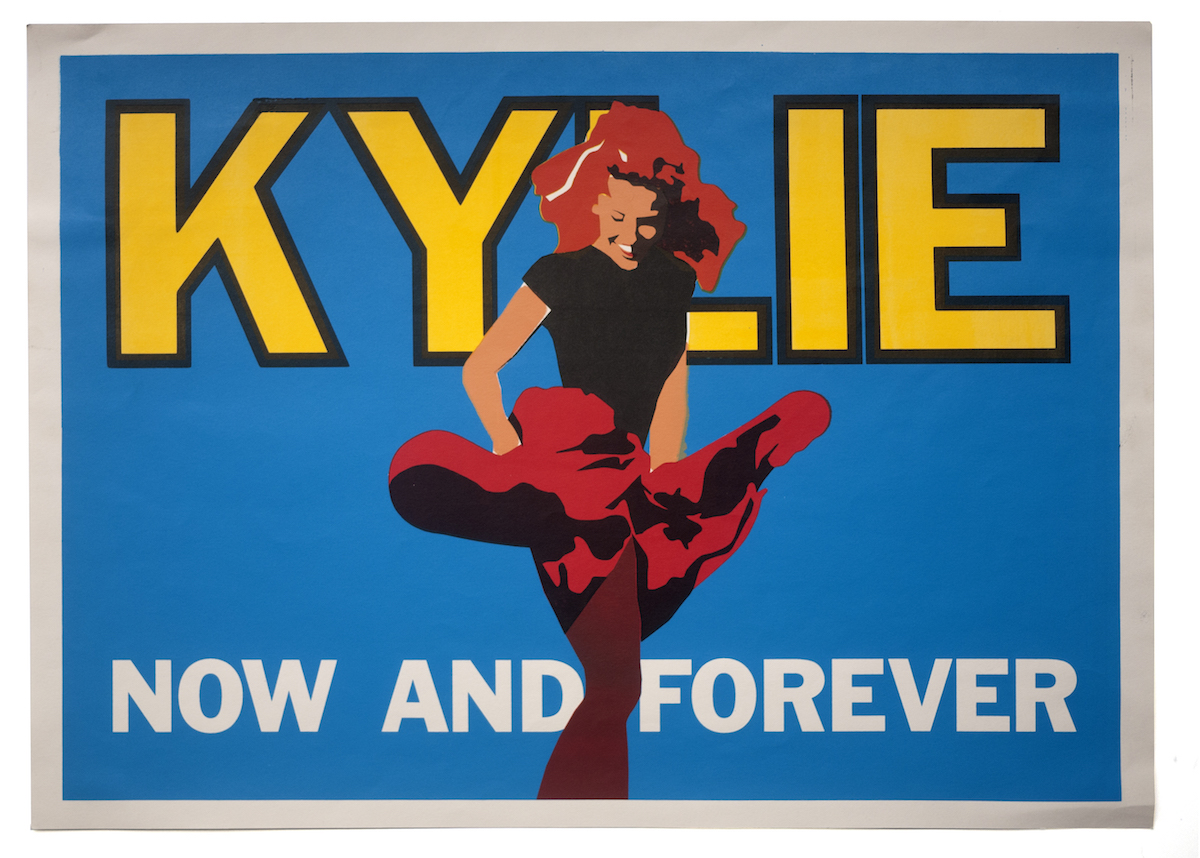

Deakin grew up simultaneously at the DJ decks and the design desk. His earliest attempts at graphic art came in the form of homemade cassette covers for bootleg gig recordings and hand-printed fanzines. When he describes his formative influences, you can sense their flavours in his own work, from the emotive 1930s and 1940s expressions of British poster painter Tom Purvis, to the sharp 1970s and 1980s record artwork of Malcolm Garrett, the vibrant grooves of US west coast psychedelia and the thrilling pulse of the indie music store. “A record shop called Honky Tonk Records on the Kentish Town Road played a big part in shaping me,” he recalls. “Fritz Catlin from the post-punk band 23 Skidoo worked behind the counter and shared his excellent tastes with me.”

It was arguably in the nightlife queue, though, that Deakin’s creative attitude was defined. He recalls being turned away at the door of an early eighties London club night called Dial 9 For Dolphin, while “an older and cooler crowd” were waved through. “It made me think: ‘I wanna be inclusive,’” he says. “There is a visual vernacular about inclusiveness; one of the nicest things about acid house was that it switched from VIP culture to smiley faces and inviting everyone to the party, where there was enough cake for everyone.”

Deakin’s own parties presented this spirit of togetherness with a fantastic irreverence. His immersive mid-eighties night Thunderball was a free-wheeling alternative to the “too-cool-for-school attitude” of other clubs in Edinburgh, where Deakin was a student. Early-nineties club Misery was also resolutely anti-cool, with a surreal playlist spanning from Scottish dance act Finitribe to porcine puppets Pinky and Perky, complemented by strange props like vacuum cleaners and chopped onions on the dancefloor. By the end of the eighties, Deakin’s vision loomed large in east London’s hip new hotbed: Impotent Fury was a monthly Friday happening at multi-level Shoreditch venue 333. Its music policy was wonderfully unpredictable—on the main floor, a gameshow-style “Wheel Of Destiny” would be ceremoniously spun every thirty minutes, and its pointer might land on anything from drum’n’bass to Europop or TV sitcom themes—and its look was vividly hypercolour. Impotent Fury’s flyers reflected Airside’s flat vector graphics (now much-imitated) and depicted varied British faces: masked health professionals, a snooker-playing pensioner. British club culture suddenly felt like an accessible work of art.

“I got the notion that you could create an iconography for yourself. I do love a bit of angst, but my thing has always been joy.”

“I was looking to brighten up the visual landscape,” explains Deakin. “The eighties and early-nineties had a very black grunge distressed feel—which is great in itself—but I wanted to explore something more friendly and inclusive, with these big silhouettes of flat colour. “I got the notion that you could create an iconography for yourself. I do love a bit of angst, but my thing has always been joy.”

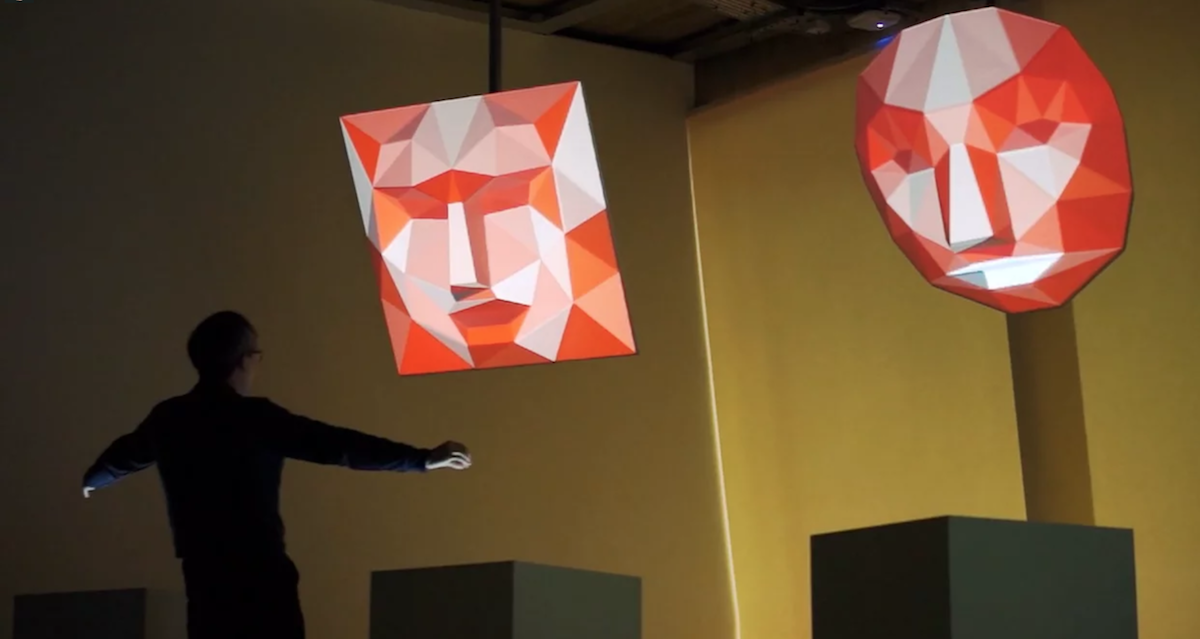

Airside also designed the playful visuals for Lemon Jelly’s trippy melodies, including highly collectible record artwork (2001 seven-inch Soft/Rock came in a denim sleeve with a condom in the pocket; their Lost Horizons album poster was reprinted in 2016) and live performance details, such as the light projections that flooded London’s Somerset House courtyard during their 2004 headline gig. Airside studio closed in 2012, and there are no plans to reform Lemon Jelly (though Deakin and Franglen are long-time friends), yet that inclusive energy endures in Deakin’s latest projects, with recurring themes of spontaneity and interaction. These have ranged from digital art installations like 2015’s Intravox (where visitors could “conduct” an ensemble of singing “alien heads”) to his current improvised shows including The Concept: an intimate east London theatre set where chaotic sketch comedy is soundtracked by Deakin constructing an album on the hoof, blending folk stylings into electronic loops.

“I love engaging with an audience, and I’ve always been drawn to work that messes with the fourth wall and really blows people’s minds. When it works, it feels like a genuine co-creation,” he says. “Allowing people to play and join in is really exciting and important. The intention is to give people the tools to create for themselves.” This aim extends to Deakin’s academic role. “What I teach at Saint Martins is how to go boldly into the unknown,” he explains. “It’s about trying to create something emotionally connected, using new technologies”.

So too, does it extend to his upcoming immersive show. “I’ve been working for four years on a science fiction concept album which has been a real journey to make—it’s almost there now. Maybe I’ll tour it alongside an improvised album show and people can judge which one is better…”

As ever, Deakin sounds ready to roll with the surprises.