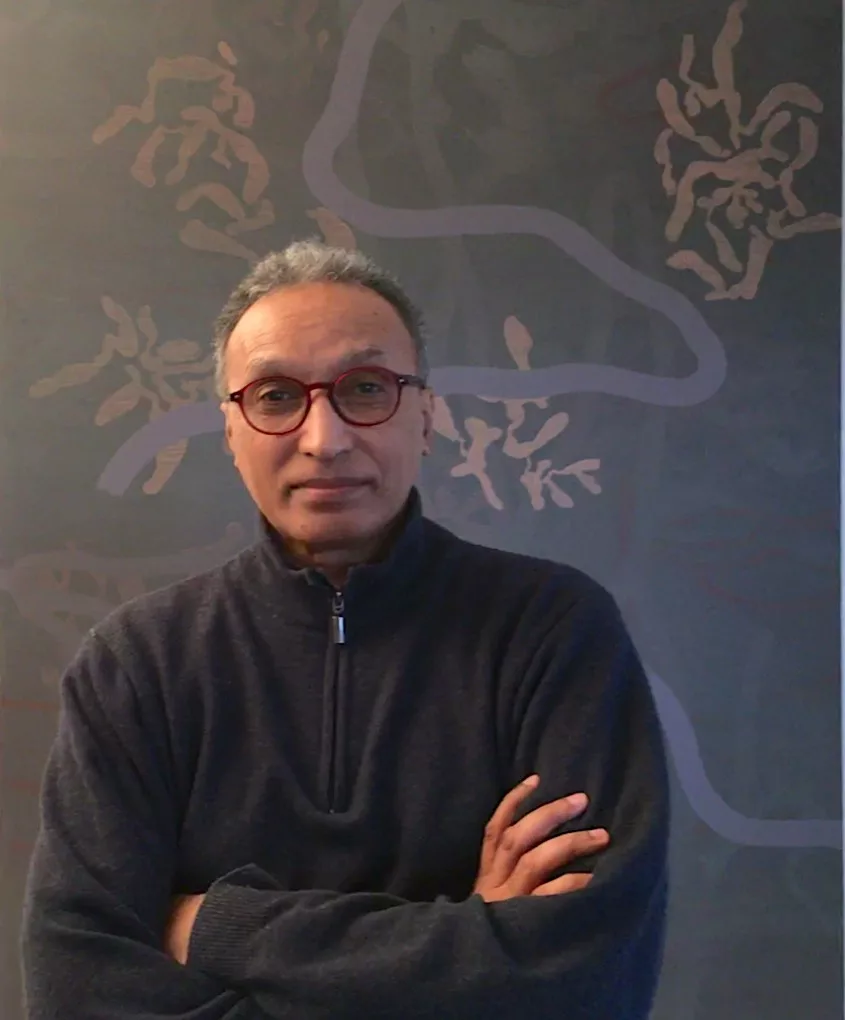

Elephant Writer, Folasade Ologundudu, speaks to South African artist and curator Gavin Jantjes about his practice ahead of his first retrospective. Sade also gains insight from art historian and curator Salah M. Hassan about the significance of Gavin’s work.

Sade: You spent a significant amount of time in exile, correct?

Gavin: 24 years. From 1970 until 1994.

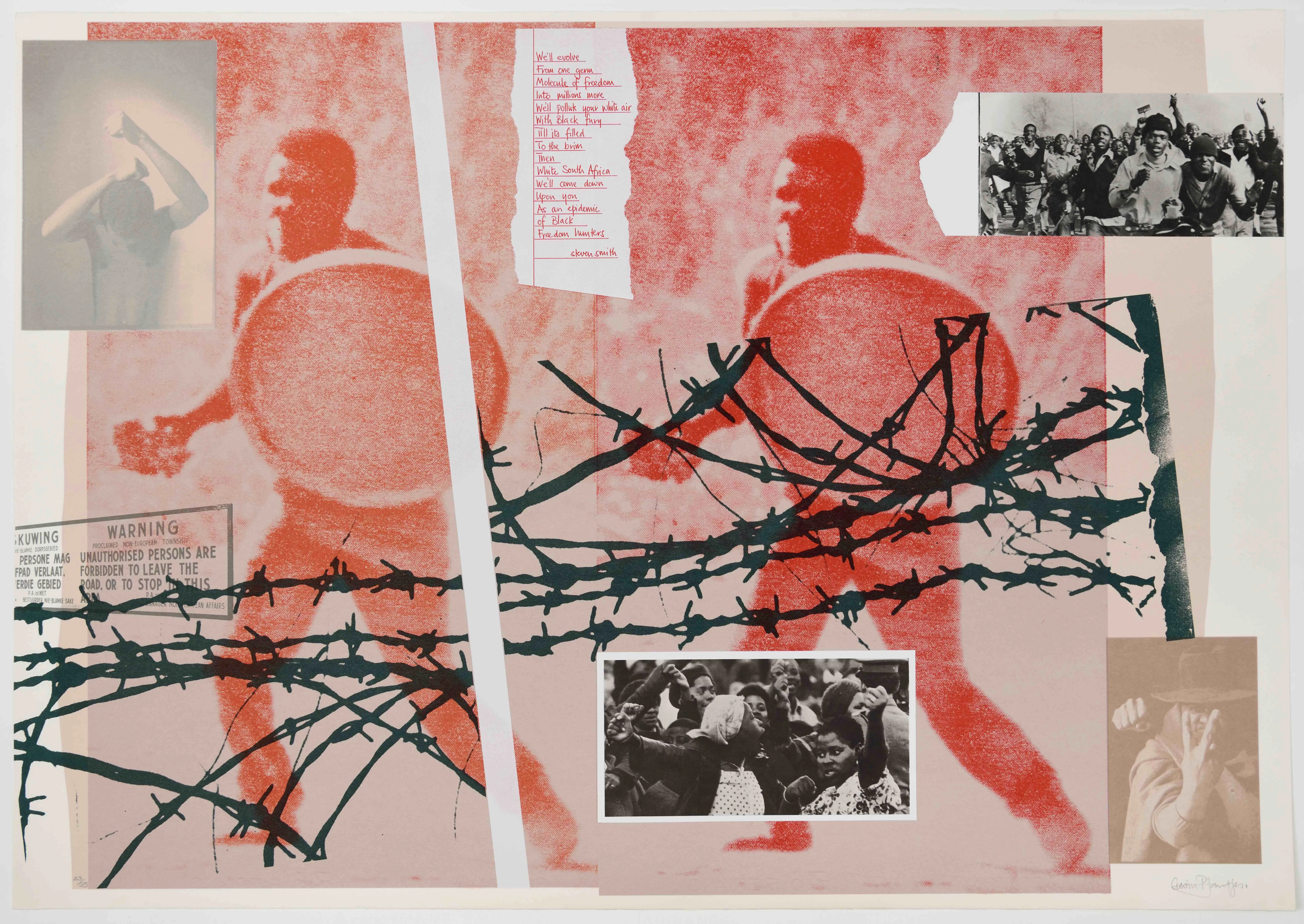

Sade: Talk to me about your most well-known work, The South African Coloring Book. What impacted you to create that body of work?

Gavin: I had a bitter experience of growing up under apartheid. When I won a DAAD scholarship to study in West Germany I began to address this inhumanity that was an official state policy. With the exception of maybe the former Soviet Union, everyone else tolerated apartheid. Their economics were connected to apartheid. Their trade routes depended on apartheid. I made the coloring book primarily for my student colleagues, who knew very little about what was happening on the African continent and in particular, South Africa.

The coloring book is an information tool which a lot of people used as education for those who knew nothing about apartheid, including the United Nations, and organisations in Geneva, who republished it in a miniature edition that was spread amongst American, West German and Swiss schools, because it was published by a Swiss organisation. That was the first time the state took official action against me. Before it was private actions, harassing me, my family, and friends as private citizens. They tried to stop me from talking about apartheid when I was in South Africa but when I left South Africa, they could no longer do this. My work was officially banned. The coloring book and two posters I made for the United Nations refugee council in Geneva. Those three works specifically were banned by the subnational state, and I was made persona non grata, which meant you could not communicate with me, you could not own any of my work, and if you did own any of my work, and dared to display it inside South Africa, you could be arrested. This coincided with the Soweto Uprising in June, and I showed at the ICA (London) around the same time in that summer. So in the art world there was a discourse that related very much to the real world, a discourse about school children being murdered by state police.

Sade: Tell me about your Zulu period. How did that series come to life?

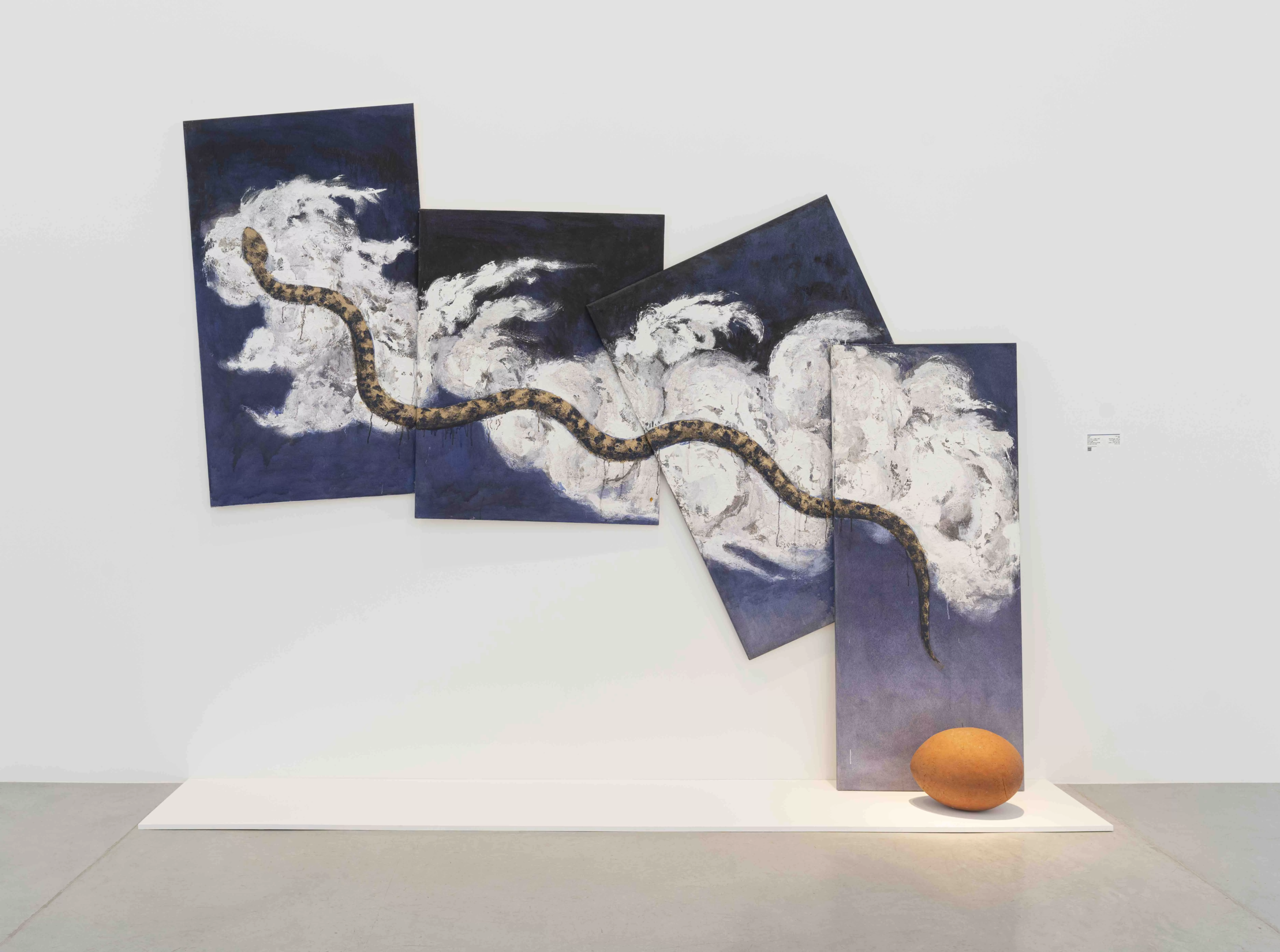

Gavin: In the 90s I moved away from printmaking and started painting the Zulu series. Just so you understand, the word Zulu, which often refers to the people in South Africa, is actually incorrect. What they really call themselves is, Amma which means people, and Zulu means the space above your head, which is the sky. So they are ‘the people of the space above your head,’ which is, in other words, God’s people. That’s the connection to the word Zulu in that series. What I did in that series was use the night sky as the background of the imagery. The research I did was related to African cosmology and astrology that starts with Egyptology and runs right through the continent. Most early African cultures and even current African cultures have a very strong relationship to the night sky. All the imagery in the Zulu series came from the understanding that the sky belongs to everyone. It doesn’t belong to any country or nation. It’s a space for every human being to engage in their own way. People have placed their mythologies, wishes, and dreams into the night sky.

Sade: I want to ask a little bit about what you’re investigating in your non-figurative paintings from 2017 to present day? What are you interested in right now, as a creator and as an artist?

Gavin: I stopped making art and became curator and director of Norway’s largest contemporary art museum, the Henie Onstad Art Center, In Oslo. I took over with a very clear plan. I was very critical of so-called mainstream institutions across Europe and the West for their lack of insight into the work of so-called artists or artworks coming from the global South. One of my big challenges was that I, in fact, was becoming a gatekeeper, like all the other gatekeepers I’d been criticizing. For a very long time I made no art. I exhibited works from my earlier life in group shows but I did not have a studio and I did not produce a single work of art.

Then after almost 20 years, I decided to go back to my studio. The question was, what was I going to do? I became more and more aware that people from the global South were being expected to make certain kinds of work. We were constantly engaging with someone else’s perceptions of us and therefore what we really wanted to do as artists was being ignored. I felt this was an urgent problem.

So the thing that I had begun to struggle with when I first made A South African Colouring Book, especially the idea about the notion of freedom came right back full circle to say to me, ‘you have the freedom of choice.’ I did not want to an apartheid artist. That was never my intention. I just wanted to be an artist in the same way that Robert Rauschenberg wants to be an artist or Jeff Koons wants to be an artist. But when I tried that people said ‘you shouldn’t be doing this. You come from Africa, you should be doing this African thing. And so these last seven years have been dedicated to that project.

Sade: One of the things that’s coming up for me is firstly, the title of the retrospective, To Be Free! and thinking about the ways in which you’ve worked to enact freedom over your career and over many bodies of work. And then leaving the studio for so long and coming back to it. What’s next for you? Are you still excited about making work?

Gavin: When I returned to the studio, I was skeptical of non figurative work. After two years, I was having so much fun. Every moment was a challenge and of course, by now, I had vast experience being an educator, writer, artist, and an institutional leader. I had a very broad perspective, at a very high level, of what the art world was about.

Many years ago, I was having an exhibition in Holland, when a young boy of 14 or 15 asked me, why did I become an artist? I thought about it for a long time. I realized, when I was 3 or 4 years old, my kindergarten took me to a children’s art center. It was the one and only Black children’s art center in the country at that time, in apartheid South Africa. The reason I enjoyed going there from a young age was that nobody told me what to do. The arts was literally the first liberal space that I could register in my life.

Being a curator and exhibiting works of artists from all over the world, I have traveled and seen a lot of art. Curators in the West do not do this. They go to the Venice Biennale or Castle Documenta and think they’ve seen the world. No, you haven’t, the world is a much greater place. Travel through India, Africa, Australia and meet artists. Travel through the southern American states and meet artists. There are millions of them and they are producing superb work that is just as good as anything coming out of Europe. The expectation that the global south doesn’t produce anything of value, is a completely dead argument. It’s been proven over and over again. Institutions can no longer deny this. Therefore, collecting on a national basis in any nation is literally absurd. You have to rethink this position of the artist and you have to rethink the expectations that the West and Western art history has of these artists and appreciate the work for what it is.

Sade: What about Gavin’s work interests you, and why do you think it was important to put on this show now?

Salah: It was really part of my own intellectual and scholarly journey to come to an artist like Gavin Jantjes. The story of Gavin came as a natural evolution of my own interest. This is a man whose lived in Europe since the 1970s and was never given his dues.

That’s my attraction to Gavin. He’s an artist whose had multiple lives, as an activist, artist, curator, and painter. And also the different movement in his life, which shows which is, we are lucky actually with the support of the Sharjah Foundation. But it’s only Sharjah that gave that kind of support in terms of providing that, supporting publications, supporting the exhibit, which is very costly, really costly. But they have the space, they have the vision, and Hoor [Al Qasimi] is a very visionary person. Really, the Sharjah Foundation has been one of the most important in comparison to anything I have seen.

Sade: Can you speak about the collaboration with Whitechapel Gallery in London and how that came to be?

Salah: I felt that the show should have been done in England, Germany or South Africa. Sharjah was willing to support it. We know Gilane Tawadros, who is the current director of Whitechapel Gallery, and a good friend of mine. We’ve collaborated a lot. She’s founding director of the International Institute of Visual Art, which is a very important institution and she was very receptive to Gavin’s show. She’s an activist and important member of the Black British establishment so it came naturally to collaborate with her.

Sade: Gavin created a new body of work specifically, specifically for this exhibition called the Sharjah Series. Can you talk about how this came about and your impressions of this newer abstract body of work?

Salah: I go back to understand Gavin’s life. When we said to be free. It is the essence of his aesthetic for his work for activism, all of them, either as an activist or as an artist or as a curator. The pursuit of freedom has been fundamental to it. Moving through the different period, as you’ve seen it, the earlier body of work, of the prints, the screen prints, which was tied to activism. his work from the late 70s, early 80s, all the way to 2000. It was all threaded through being an activist, meaning it has always had a political value, Then came the period in the 2000 when he moved back to England. He decided to go into non figurative form. He doesn’t even call it abstract. He insists on calling it non figurative.

Sade: In your opinion, what is important about Gavin’s work, and how is it relevant to the social and political conditions of the contemporary moment we’re living in?

Salah: The idea of freedom is very important. If you look at today’s conditions, apartheid still exists. The only way international capitalism can work is through an apartheid system. The relevance of Gavin’s work is that we see a replay of the issues that he fought against still happening today. The pursuit of artistic freedom is so important.

Written by Folasade Ologundudu