If you were walking through Trafalgar Square last spring, you might have caught sight of a glistening Lamassu standing on top of the Fourth Plinth

, the empty spot that is now a platform for challenging contemporary art. This winged bull deity was a replica of the sculptures that stood at the entrance to the Nergal Gate of Nineveh (now Mosul) for thousands of years, until they were systematically destroyed by Isis in 2015.

While these ancient carvings were reduced to rubble, Iraqi artist Michael Rakowitz began resurrecting their forms to scale, using Middle Eastern foodstuffs. His Fourth Plinth Lamassu was constructed from hundreds of date syrup cans, alluding to the enormous trade that once heralded Iraqi dates as the best in the world, and the complex processes that allowed companies to export their products during UN sanctions, from 1990 to 2003.

- Michael Rakowitz cooking at Felix Refettorio, London; Asma Khan, Tangra chicken kebabs. Photos by Joe Woodhouse

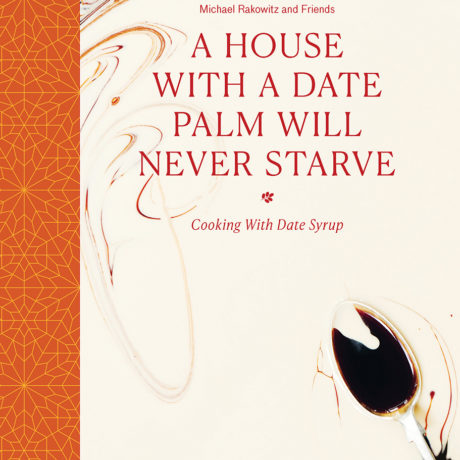

Now, Rakowitz has published a new cookbook, titled A House with a Date Palm Will Never Starve (which borrows from an old Mesopotamian proverb), which coincides with his major exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. “This cookbook seeks to extend the space of Lamassu beyond the Fourth Plinth into your cupboards and bellies,” he promises. The result is an incredible mix of traditional and modern recipes conceived by “Michael Rakowitz and friends”, including renowned chefs such as Prue Leith, Yotam Ottolenghi and those who span the genres, such as Iraqi artist and food writer Linda Dangoor, not to mention Rakowitz’s own mother, Yvonne.

Cooking with date syrup in the Moro kitchen. Photo by Caroline Irby

These collaborative cultural exchanges are not only mouth-watering, but are also peppered with family anecdotes, childhood memories and even political history. Dangoor, for example, recalls buying turnips on the way home from school in Baghdad before relaying her short and sweet recipe for Shalgham helu; while Rakowitz explains the cultural erasure of Masgouf, a national dish of barbecued fish with date syrup marinade: “Dating back to ancient Babylon, the basic recipe consists of a fresh carp fished from the Tigris River […] In 2007, Baghdad’s imams issued a fatwa on the carp swimming in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, declaring them unclean and unfit for human consumption due to the large number of corpses floating in the waterways.”

- Left: Soli Zardosht, Roasted sea bass; Right: Brett Redman, Olive oil, yoghurt and date syrup cake. Photos by Joe Woodhouse

These brutal truths lay bare the horrors and violence of the conflict, and it goes without saying that these aren’t facts that you would usually find in a recipe book, but Rakowitz’s ability to embody the flavour of a complex cultural heritage, the diaspora and its many intersections is what makes this book a joy to read, whether or not you plan to actually cook anything.

“This book serves the notion that culture is best absorbed via the stomach”

It is also a wonderful way to learn about the artist’s long relationship with food, which forms an integral part of his practice. For example, he cooked with London schools during his Fourth Plinth tenure to spread information about the project and its origin, and he launched Enemy Kitchen back in 2003. This “itinerant cooking workshop” that began as Baghdadi cookery classes and developed into a functional food truck in Chicago, which was staffed by Iraqi refugee chefs and US veterans of the Iraqi war as their sous chefs, as a way of inspiring healing conversations and collaboration as much as producing delicious food.

He also launched a pop-up restaurant called Dar Al Sulh (Domain of Conciliation) in Dubai, which celebrated Iraqi Jewish dishes—it was “the first in the Arab World to serve the cuisine of Iraqi Jews since their exodus, which began in the 1940s”.

All in all, this book serves the notion that culture is best absorbed via the stomach. Covering everything from fried chicken to cocktails, it shows the incredible versatility of an ingredient many of us will swear we have never tried, and infuses the joyous spirit of shared meals with cultural knowledge that goes far beyond the reductive headlines of conflict.

Rakowitz calls on an age-old custom to exemplify not only the importance of the ingredient he has become so obsessed with, but his ever-optimistic outlook: “In Iraq, it is traditional for parents to place a date in the mouth of their newborn baby, so its first taste of life is sweet: a harbinger of things to come. Here’s to a sweet future.”

A House with a Date Palm Will Never Starve

Published by Art / Books in association with Plinth

BUY NOW