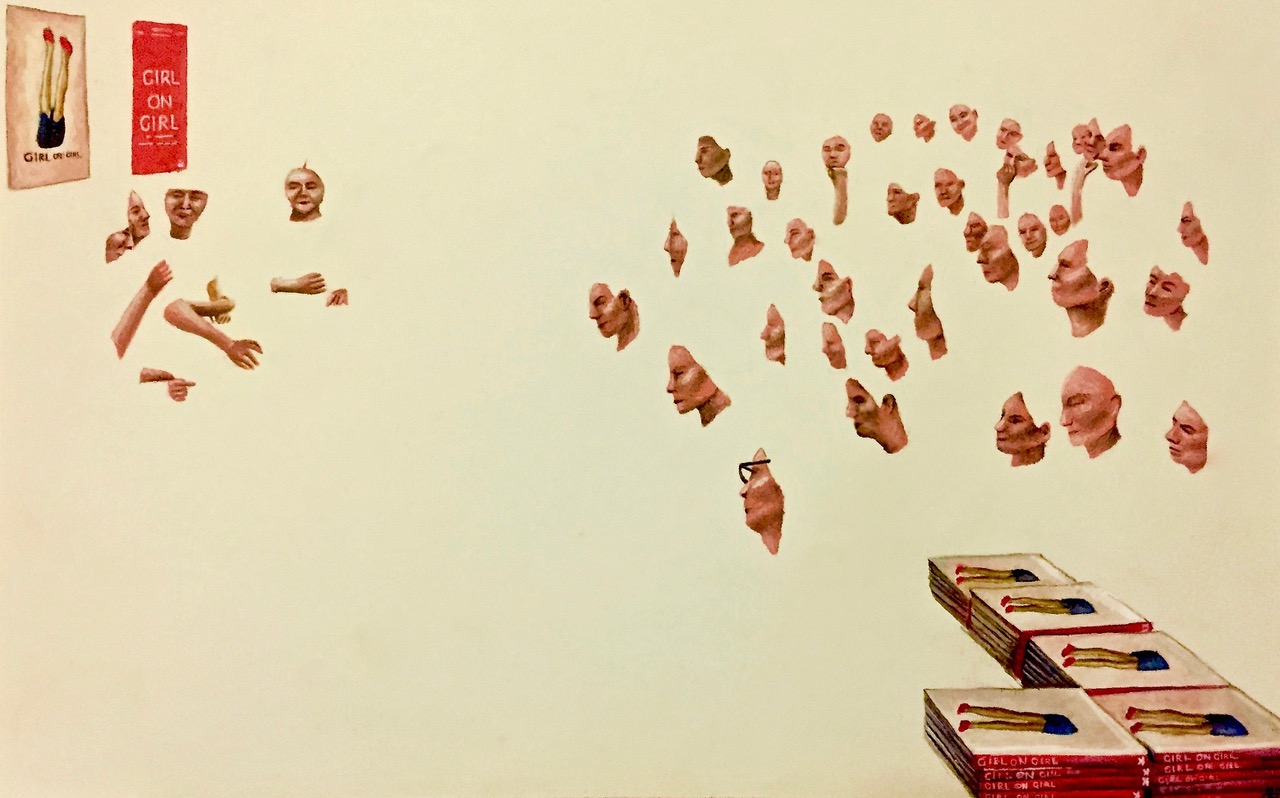

Charlotte Jansen is endlessly inquisitive. As a regular contributor to Elephant magazine, and Editor-at-Large for the past few years, her selection of artists and subjects is consistently bold, curious and boundary-pushing. For Girl on Girl, an image-rich book which invites forty artists to discuss their practice with Jansen, there is the sense that, while every artist adheres to the simple principle of being female and photographing females, there are a broad range of approaches represented—not all of them aligning with a straightforward view of feminism. From Maisie Cousins’s sumptuous, wet and fleshy photographs to Yvonne Todd’s plastic, suburban shots of manikin-like individuals, we see the female body, life and aesthetic reclaimed by women, for everyone.

We gathered the female contingent of Elephant–Jansen, Emily Steer and Molly Taylor–to find out more.

Emily Steer: Where did Girl on Girl begin for you? Was there a particular artist or group of artists who you first engaged with?

Charlotte Jansen: I had been looking at a lot of photographs online, and reading and writing a bit too about this new movement—or perhaps trend—with female photographers like Petra Collins, Mayan Toledano, Dafy Hagai and Arvida Bystrom. From there I started to think about how women are either commercialized or criticized for doing this kind of work with their bodies.

ES: How would you describe the artists featured in Girl on Girl in a few words?

CJ: Visualizing a world that doesn’t exist and that we haven’t seen before. And not all feminist…

Molly Taylor: That’s interesting. As a young woman working in contemporary art (which, despite its wealth, is ostensibly made up of quite a liberal bunch), I always just assume everyone’s feminist. Especially the artists. What kind of signifiers were there that some of the artists weren’t engaged with (or actively opposed) that movement?

CJ: I suppose it’s not that they wouldn’t call themselves feminist, but that their work isn’t necessarily. I think when we see the art women make about bodies we automatically assume the motive is feminist, but bodies are only bodies. Assuming everyone is feminist is good and I think it should be a given, but insisting this kind of work is feminist first keeps it in this narrow category of art that is very marginalized and understood as only interesting to women. Feminism is still a very narrowly perceived thing.

By the way, I’m surprised you assume most people in the art world are feminist: it seems to be a very masculine and phallogocentric world to me!

MT: I guess I mean that, if asked, most people at an art opening, say, would be like, “Yeah, yeah, I’m a feminist.” Even if the structure of the art world in reality disavows those values.

CJ: Yes, that’s the worst kind of feminist! We need to see real things happening.

ES: In the introduction you describe Mayan Toledano’s Sherris in Palm Springs making you feel angry when you first encountered it, which I can really relate to! You also mention that not all of the artists featured in the book are necessarily “pro-women”. Have you collated your group of artists with any boundaries at all in mind, or have you tried to keep this as open as you possibly can?

CJ: Yes, I feel a lot of anger towards photographs!

MT: What kind of anger?

CJ: I’ll see magazine covers and feel enraged sometimes, or my blood will boil at ads on the tube. Once you start noticing the sexism in our photographic language, you realize how endemic it is. It was very important to me to explore what those images are really doing in our current society, to try to get deeper into how we see, and question why we see women the way we do and how women might be contributing to that, or changing it.

ES: Are there any artists in the book now whose work you still find confronting?

CJ: Yes. But I think it’s important to have a discussion with everyone, because some of the photographs I find difficult from a feminist perspective are some of the most influential and popular now. It’s also good to remember that we don’t all agree: you can’t say all women photographers approach their work in the same way. I think through the book I also discovered how complex our experience of looking at women is and how hard it is for women to move forward. Especially when it comes to sexualized images.

MT: Yeah, it seems clear that there is a palpable disdain for women taking and distributing sexualized images of themselves online, but there’s also a backlash that points out this disdain only occurs when the women themselves are in control of the image—rarely when they’ve been produced by men. Did your research for the book influence the way you saw this conflict?

CJ: Definitely. The online-only exhibition Body Anxiety (2015)—which will no doubt be seen in years to come as a really pivotal exhibition—shed a lot of light on this topic in particular for me too, as well as some of the debates I got into on Twitter after I wrote about it. It was curated by Jennifer Chan and Leah Schrager (who appears in the book). Women who decide to photograph themselves or other women have a lot of challenges to face. It’s one of the areas that’s the most difficult for women to do anything in, because our response to women in photographs is so strongly conditioned.

MT: Some of my favourite work in the book is by Chinese artist Pixy Liao, who photographs herself and her boyfriend posed in surreal, funny images that play with the representation and roles of gender in relationships. How did you come across her work? And what made you feel strongly about including it?

CJ: She’s great, isn’t she! I really like how honest she is in her interview too, she isn’t a feminist and she doesn’t think the genders are equal. I came across her work at an exhibition at Flowers Gallery in New York, in which Juno Calypso was also included. I really wanted more artists from outside the West in the book but it’s really hard to get to them, with the language barrier, and particularly in China, with the fact they don’t have Instagram. Liao is now based in NYC and speaks very good English so it made her work accessible to me. But I think there’s a lot more work to be done there, I’d be really interested to know more about the practices of women working with their bodies in contexts outside the West. As Liao also told me, her work wasn’t really appreciated as much in China. Different cultures of course have really different attitudes to gender, sexuality, bodies. I think I only just begin to touch on this through the artists in the book, but would love to explore it more. I don’t think the Western perspective is the default.

ES: You mention it being more difficult to engage with artists in China due to the lack of Instagram, and also feature artists such as Alexandra Marzella in the book, who have really developed their practice on Instagram. Do you think the existence of social media has helped propel the female gaze in photography more so than other mediums, or do you feel this is reflected throughout the wider art world?

CJ: I think social media has completely overturned everything. The female gaze was a concept confined to the academic world before that, now it can be applied to our entire visual culture. Social media has exploded the concept of visibility, of how and what we see, and how we respond to it. Almost as interesting as the photos and videos Marzella posts, for example, are the comments she gets.

ES: On the flipside of that, social media has also allowed even more objectification of women, as well as showing up inconsistencies in how the male and female bodies are censored. Is it possible for artists to keep up?

CJ: I think social media has made the discrepancies, like you say, between how we look at male versus female bodies, very obvious and visible, more so than ever before—perhaps that’s also contributing to the urgency we feel to change things now. It’s as if we’ve just started from the beginning again online, negotiating all of these issues of censorship as women artists have had to in the past. I think that slowly the gaze is shifting, though, as more and more women are now in control of the images we see.

ES: Since creating the book have you come across artists who are already doing something completely new? Who would make it into a sequel?

CJ: I genuinely feel they’re all doing something new. I’m not trying to say that everything is original, there’s a historic root for everything if you want to trace it back, but it’s new to the times and context we’re living in.

ES: And do you have any particular favourites in Girl on Girl?

CJ: It’s hard to pick, because there are so many! I suppose among the work I connect most to, that speaks the most to me personally, would be Pinar Yolacan, who approaches so many different questions through her depictions of female bodies, the female gaze on colonialism, art history, culture, fashion… I love the fact she makes her costumes by hand for each of her subjects—with things like meat and Latex—she’s really creative. It also takes her years to complete each series, it’s not just a point-and-shoot job.

I also discovered Yvonne Todd’s work in the process of doing this book, whose pictures are so dark, sardonic and weird. On the other hand I really love Jaimie Warren because she is so much fun and exploring the theatre of the self with so much colour.

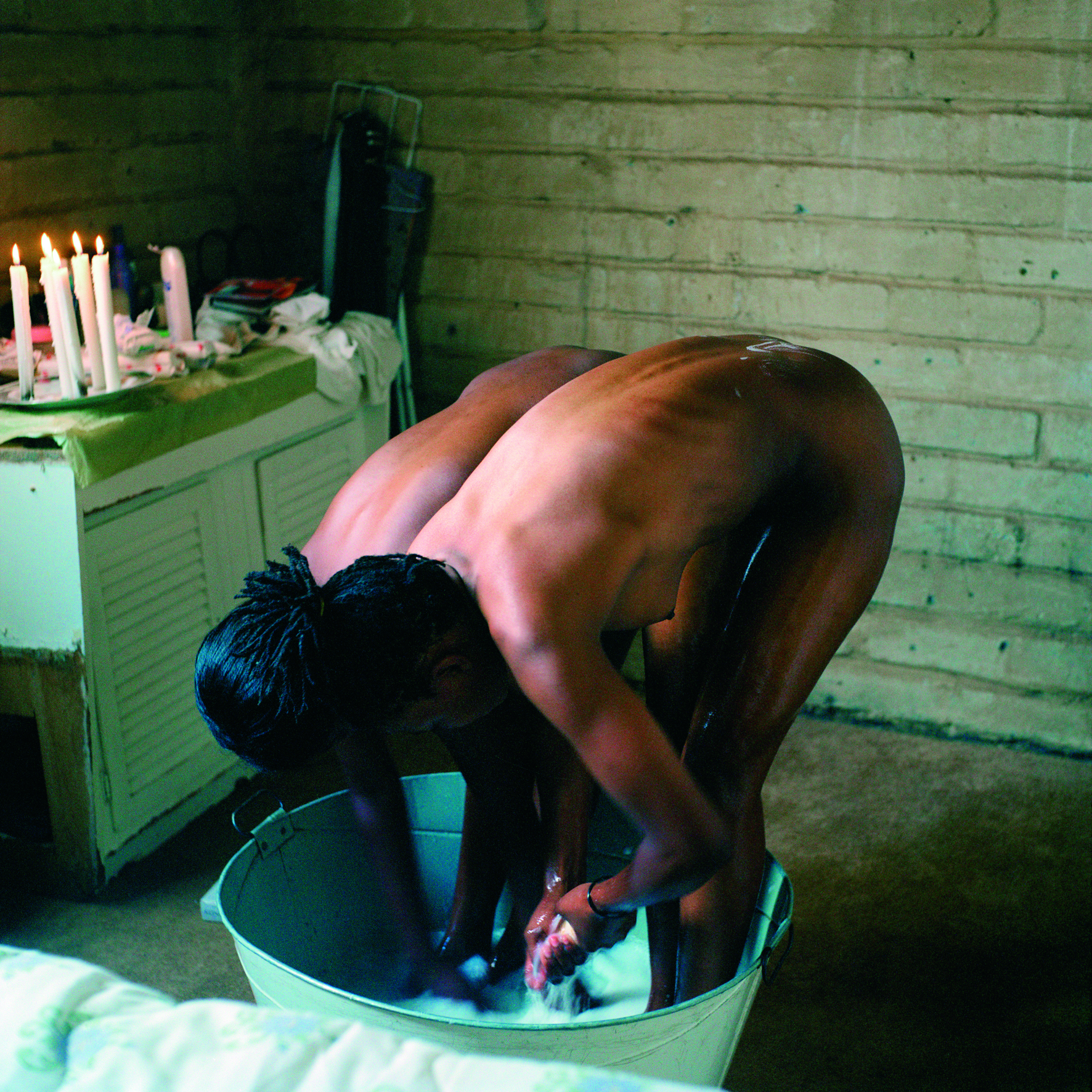

I have to mention Zanele Muholi. Her project is so inspiring. She’s seen awful things happen in her community—to people she knows, people who have been killed or attacked or raped because of their gender or sexuality—yet she manages to produce such power, so much beauty, in her photographs, and really show the dignity and humanity of her subjects.

But I really hope everyone will find their own place and their own inspiration in this book, whatever their gender. There’s so much you can take from these pages if you’re open to it.

‘Girl on Girl’ is out now with Laurence King Publishing. You can buy Elephant Issue 25: Girl on Girl from our website. Original painting from Girl on Girl launch by Harriet Lloyd-Smith.

Zanele Muholi. Beloved I, 2005, courtesy of the artist