The legacy of Ishirō Honda’s 1954 cinematic triumph, “Godzilla,” extends far beyond the big screen. Unfolding against the backdrop of post-war Japan, devastated by atomic bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a dormant leviathan, mutated by nuclear testing, emerges from the Pacific Ocean and wages war against humanity. For a group of Asian American artists reckoning with the exclusionary policies and lack of representation in the art world in 1990, Godzilla became a fitting moniker. The metaphorical resonance of the anarchist lizard’s emergence, reflecting the consequences of nuclear testing and the struggle for recognition, mirrored the artists’ own challenges and their determination to reform the tide of hegemonic American consciousness.

In the largest and arguably most indicative exhibition to examine Godzilla to date, Eric Firestone Gallery mines the motifs, interventions, and shared dialect of the Asian American Arts network to offer a glimpse into the nuances of artist collective formations and raise questions around the aesthetics of diaspora. GODZILLA: Echoes from the 1990s Asian American Arts Network spans two spaces in their New York gallery, featuring established artists whilst amplifying the voices of those who have not been centred in the canon and who made their careers showing in alternative spaces.

The 1990s marked a pivotal era for people of Asian heritage in the United States. The decade followed the 1965 federal rulings that eliminated long-standing exclusionary immigration quotas previously restricting the composition and size of Asian America. Concurrently, refugee statutes enacted in the aftermath of the Vietnam War triggered a significant surge in new migration and settlement. During the period from 1980 to 1990, the total Asian Pacific American population witnessed a remarkable growth of 95%. In its earliest iteration, Godzilla comprised of just a handful of artists – Byron Kim, Ik-Joong Kang, Arlan Huang, Bing Lee, Ken Chu, Margo Machida and others. All of whom convened at cheap joints to discuss identity politics and the formation of a lateral network of creatives in what was casually referred to as the Tuesday Lunch Club.

“The primary catalysts for the founding of Godzilla included Chu’s interest in forming an Asian American Museum, Machida’s desire for investment in Asian American culture, and Lee’s desire for community and networking,” exhibition curator Jennifer Samet tells Elephant. “Their first meeting notes established goals, which included education and discussion to foster information exchange and mutual support, connecting with critics and writers qualified to write about AA.”

As a result of its open membership policy and the popularity of its eponymous newsletter – designed by Charles Yuen with punchy graphic and a humorous spirit – the network had reached over 2,000 members nationwide by 1995. Subsequent gatherings ranged from loft parties, where food was brought and shared, to structured panels, presentations, and ‘slide slams’ culminating in several group exhibitions and interventions.

Godzilla traced its lineage back to the Asian American movement on the West Coast during the late 1960s and, more specifically, to Basement Workshop, established in 1970 in New York’s Chinatown. Responding to the evolving socio-political and racial landscape in the United States, they drew inspiration from emergent identity-based organisations and motions such as Third World internationalism, the Black Power movement, the Chicano movement as well as the anti-war, labour, and feminist movements. Interconnecting political activism with artistic creation, Godzilla’s ethos was deliberately undogmatic, allowing for a nimble evaluation of the hereditary and contemporary challenges it faced: institutional racism, Western imperialism, anti-Asian violence, the AIDS crisis, and representations of Asian sexuality and gender, among other urgent issues.

One of Godzilla’s earliest actions was perhaps its most significant. In collective protest, members, including curator Eugenie Tsai, wrote a letter to then-director of the Whitney Museum, David Ross, decrying the absence of Asian American artists in their 1991 Biennial and offering to put him in touch with their network. “The letter had a direct and substantive impact,” says Samet. “It established a dialogue with not just the Whitney but other New York museums. In the fall of 1991, Godzilla members were invited to a meeting with Ross, submitted slides of 12 artists, and participated in a panel discussion. The next Biennial in 1993, was notably invested in identity-based work, including Asian American artists’ representation.”

Still, in the years Godzilla was active – from 1990 to 2001– Asian culture was often pigeonholed into a narrow perception, artificially held in a static state of antiquity, or relegated to cultural studies. Despite the strong intellectual basis of the art produced, institutional frameworks consistently failed to incorporate this richness into their programs. Consequently, from its conception, Godzilla sought to differentiate its goals from that of a museum, eschewing institutionalisation or corporate funding structures and curating alternative spaces to feel validated.

Eric Firestone Gallery represents several African American artists involved in identity-based collectives, including Joe Overstreet, Kenkeleba House, Ellsworth Ausby, and Cinque Gallery. Following the unprecedented growth of the Asian American population in the past thirty years, it became clear to Samet that efforts to redress decades of institutionalised racism and ignorance were also needed for this community of artists.

“Setting the curatorial parameters for the gallery’s latest exhibition proved difficult,” she shares. “As well as artists, Godzilla had also included art historians, writers, and cultural producers.” In resolving to exhibit historical works spanning photography, painting, performance, sculpture, and collage alongside a vitrine of ephemera and more recent commissions from Godzilla’s members, the gallery honours the non-hierarchal, open-ended structure of the network, fanning the fire of transhistorical collaboration.

Ranging from evocations of community, belonging, and heritage to expressions of a more elusive and ephemeral nature, individual artists, past and present, are given due space to negotiate their evolving relationships to ‘Asian-ness’. As Godzilla founding member Margo Machida writes in the foreword for ‘Envisioning Diaspora: Asian American Visual Arts Collectives’ (2008) this Asian-ness “confers a viable means through which artists can view and address contemporary society.”

“Much of the work in GODZILLA contends with and draws attention to the traumas and savagery of colonialism, war, and persecution, which, of course, led to these multiple diasporas but also transform the show into a transcendent, beautiful, and playful aesthetic experience,” Samet adds.

For the last ten years, founding member and multi-media artist Bing Lee has been building a body of work which pursues a line of communication between his early life in Hong Kong and his time in New York. The glyphic tiles in Truth (Pictodiary #1) underline his desire to create an alternative language, neither Asian nor American. “When I moved to New York in 1979, I posted my works on walls in lower Manhattan for some time,” Lee recalls. “Since initiating the ongoing project Pictodiary in 1983, I have committed to making iconographic images every day, which relay memories, fantasy, and social concerns. These images are a visual vocabulary.”

Like Lee, Charles Yuen joined the network in the early days before the gatherings had even been given a name. Yuen is a third-generation Hawaiian with a hyphenated identity – Chinese-Japanese-American – which he tells us “seems to have engendered a sense of dislocation with a dose of alienation.”

In his existential oil painting Invisible Man (1984), linear elements containing Chinese queues (hairstyles) inscribe themselves in an undulating landscape that, when viewed with greater perspective, reveal a face, prompting us to unpack the scene like a surrealist riddle. “Abstractly my alienation visually manifests in a quietly catastrophic, receding space collapsing in on itself,” Yuen shares. “Within this context, the subjects of my paintings vary, largely focused on exploring the human condition influenced by current events. I work at finding qualities embedded in these events with the potential of transcending topicality.” Jug Boy (1994) for example is anchored in a notion of flexible narratives. “By placing pictures within pictures, I wanted to create stories that would change depending on the viewer’s disposition at any particular time.”

The expressive visual practice of Helen Oji, a third-generation Japanese American, first came to the attention of the New York art scene in the early 1980s. Her Kimono series featuring pseudo-origami-shaped paper thickly layered with acrylic and rhoplex evolved to incorporate abstract and explosive phenomena as well as allegorical meditations on her Japanese heritage. In the painting Give and Take (1994), exhibited at Eric Firestone Gallery, Oji centralises the teapot to limn an exchange of communication between past and present. The metaphysical composition – in which a smaller teapot contained within itself pours into a spool of loose thread – calls to mind a Matryoshka or stacking doll, a symbol of Russia whose real origin is believed to be Japanese. “In this painting, I was thinking about my relationship with my mother and what I learned from her about her keen gifts of sewing and constructing garments,” Oji shares. “For me, the teapot is an iconic shape. It is a symbol of friendship, storytelling, and conversation. In the Japanese tea ceremony, the teapot is a central character in a complex dynamic between participants. Each utensil used symbolises peace, harmony, and hospitality. It has a positive impact, emphasising beauty, simplicity, mindfulness, patience, and care.”

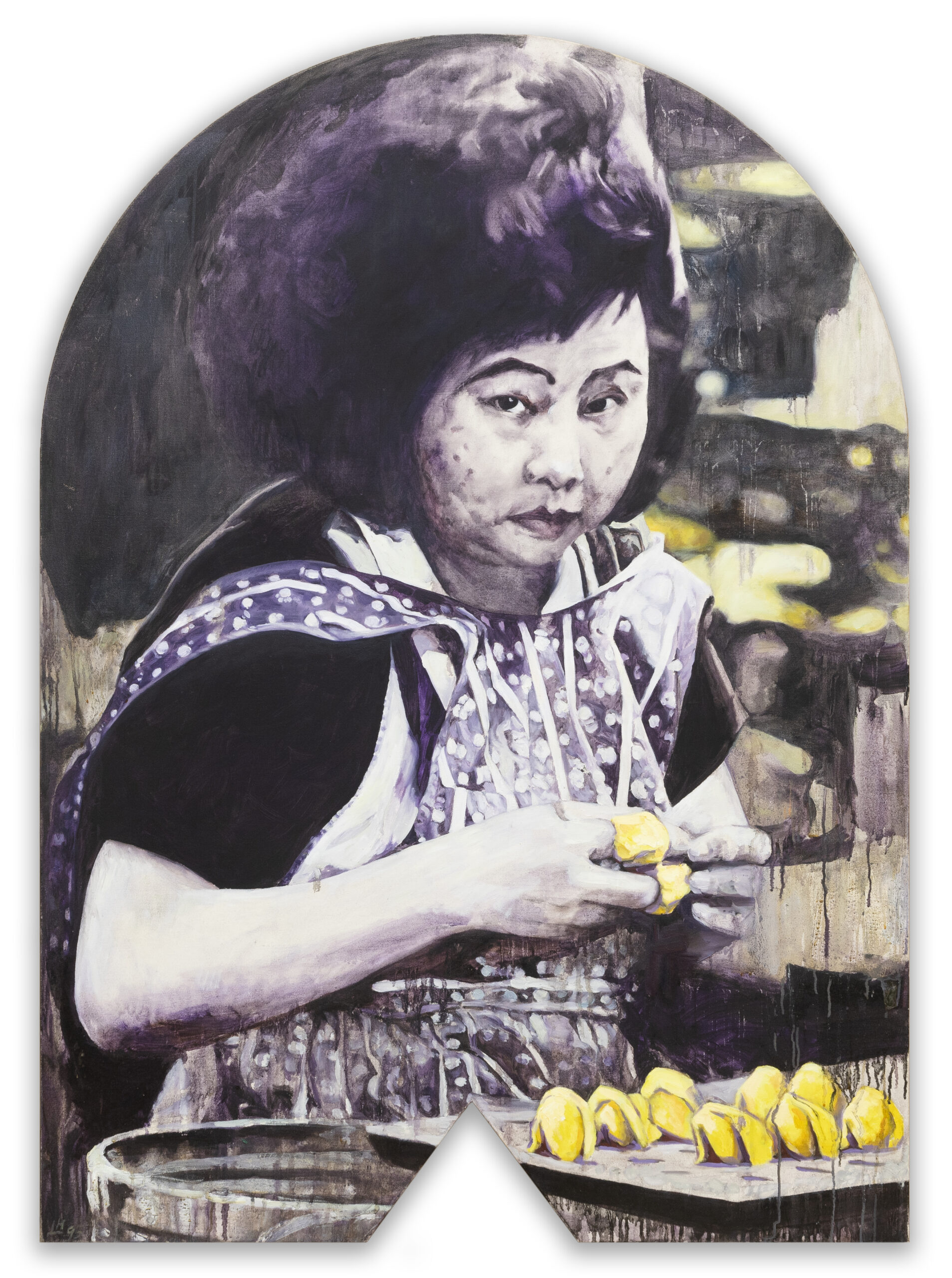

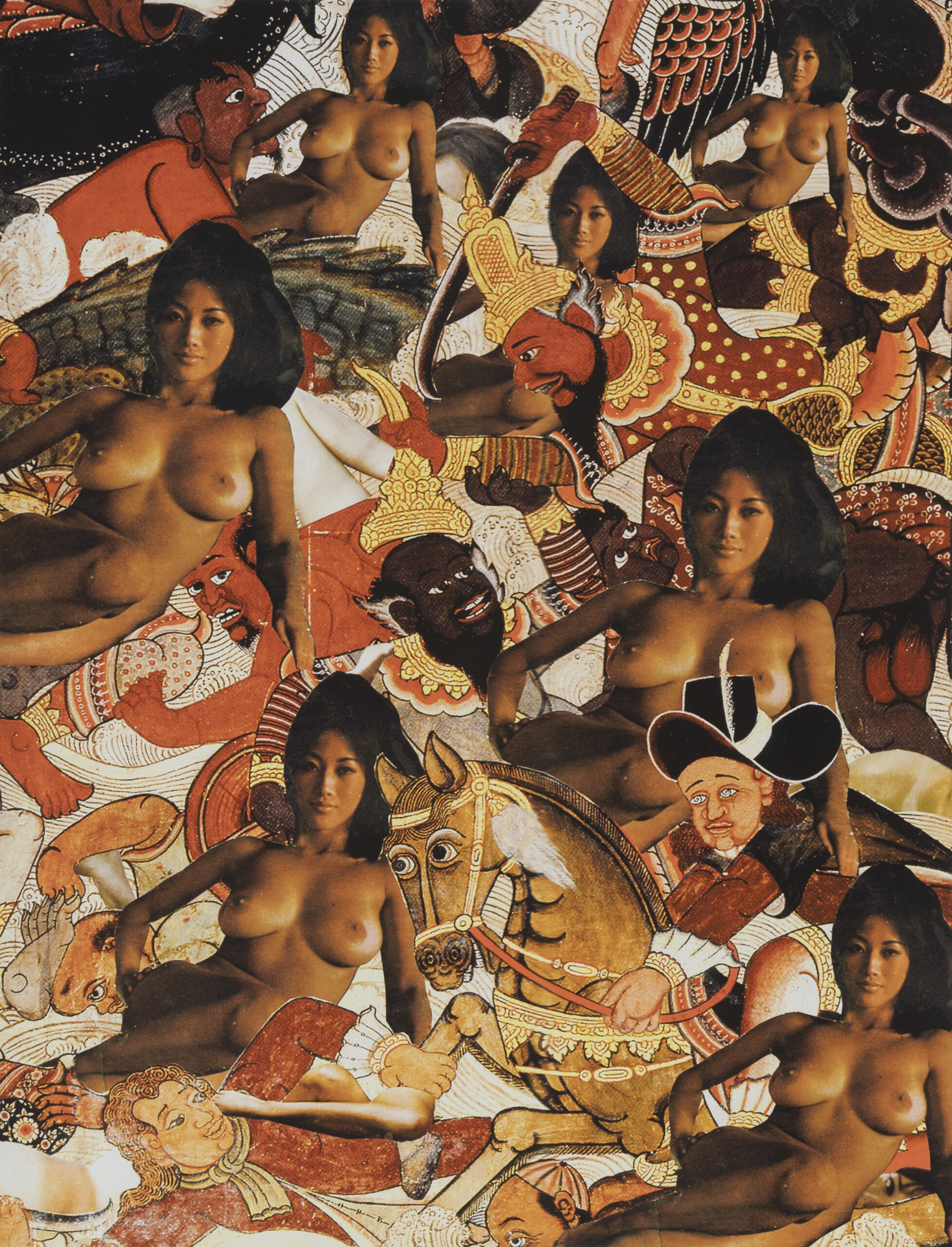

Elsewhere in the gallery, multi-media artist Skowmon Hastanan presents a carefully restored sculptural assemblage piece originally presented in Godzilla’s 1993 exhibition The New World Order III: The Curio Shop which appropriated the notion of a Chinatown curio shop to underscore the exoticisation of Asian people and culture. Drawing upon her background as the child of two doctors stationed at the Thai-Laotian border during the Vietnam War, Hastanan recontextualises images of sex workers and Playboy models to draw attention to the sex industry in Thailand and the objectification of Asian women in modern American media.

While some may suggest that Godzilla’s plight for collective visibility is inherently political and that their various actions did indeed have political implications, what unified the group and mobilised members were issues pertaining almost solely to the practice of visual art. “I do not consider the artistic content of my work to be political,” says Oji. “Being an artist and an Asian American woman does politicise me in some ways, but what I appreciated about Godzilla was the synergy of camaraderie within the collective that made things happen. Through the group’s newsletters, I was exposed to even more artists and exhibitions featuring AAIP artists across the country. It was great to know how many people like me were out there in the world whose artistic interests were similar to mine.”

The pieces comprising GODZILLA, then, demand to be approached with the same disparate way of viewing the world that they depict. Meeting in what Yuen describes as a “Venn diagram of experiences”, are textured and dynamic engagements with diasporic experiences and multi-hyphenated identities. Relying on matrices of relationships, the network confronted the inhospitality of the 20th-century contemporary art scene with gusto while simultaneously imagining an Elysium of pan-Asian unity. As such, when the group dissolved in 2001, it was by no means the end. “The spirit of Godzilla continues and can be felt throughout the exhibition,” reflects Lee. “It serves to prove the perpetual importance of co-existing across multiple standpoints of heritage, tradition, arts and culture.”

Written by Millen Brown-Ewens