London might be under lockdown, but I’ve been travelling more than ever. Last week alone, I aimlessly strolled around the central French city of Blois in search of its chateau’s double helix staircase. After reading a novel set in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, I wandered through Grahamstown, and then headed to the waterfronts of Recife, Brazil, striving in vain to find the apartment building at the heart of the film Aquarius. Even the pandemic is taking me around the world: a news report took me to Crema in Lombardy, which in turn led me to wander around the nearby town of Caravaggio, intrigued by its potential connection to the painter.

“I’ve started playing little incomprehensible games. Put yourself on the edge of a Spanish town and try to get to the Plaza Mayor in as few clicks as possible”

These vicarious journeys were all made through Google Street View, the ultimate facilitator of armchair travel. In the best of times, barely a day passes when I don’t plonk the little yellow man down in some barely notable town that I’ve stumbled across while working. Confined to the house, my habit has become rabid. I can barely read or watch anything without jumping into the app. What might be hours have passed by while I try to make sense of downtown Los Angeles and survey the exurbs of Naples, all in a halting variant of the silent film phantom ride.

I was a latecomer to the joys of Street View. When it initially expanded to the UK in 2009, I remember feeling discomfort that the places of my personal life were online for all to see, failing to consider that such things would be of interest to almost no-one else. I’d long been obsessed with cities—as a child I dreamed of designing them for video games—but failed to make the obvious connection. And there was also the worry of denuding unseen places of their excitement and mystery.

My addiction came much later, from a combination of precision and procrastination. While writing, I would often mention buildings that I had not seen first-hand, or if so not recently. I wanted to provide some context as to what, say, an artist’s studio looks like, what it abuts, what sort of area it sits in. I also relished having a justifiable distraction from the work at hand. Once dropped on the street, of course, it was difficult to step back. Minutes would pass by strolling, always at a strange, just-above-human height.

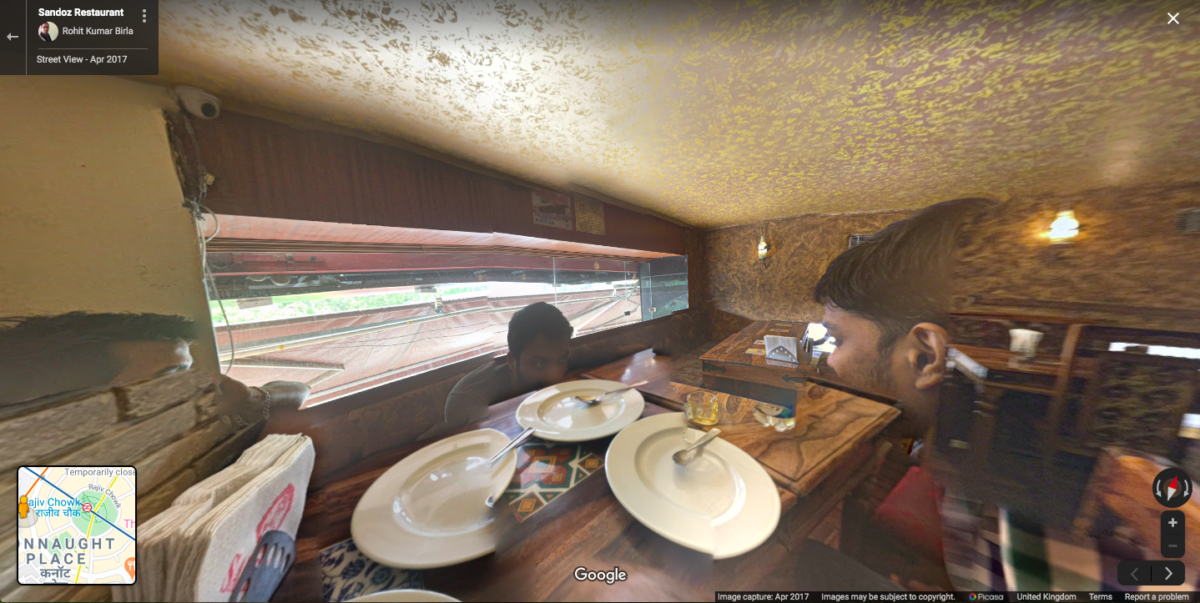

- Phantasmal forms in a New Delhi restaurant

It didn’t take long for Street View to transition from work aid to leisure pursuit, indulged whenever I have a moment to spare and often when I have not. I’ve started playing little incomprehensible games. Put yourself on the edge of a Spanish town and try to get to the Plaza Mayor in as few clicks as possible, counting all the jamón shops along the way. I wonder at the strange glitches, where people become translucent or a building appears twice its actual height. Housemates have more than once entered the sitting room to find me red-faced, trying to scroll around a German town where only small fragments of streets are covered.

Street View is never perfect. Views are spoilt, as in life, by other vehicles. The insertion of additional photographs by users can both frustrate and delight. There seems to be barely a hair salon in the world, for instance, that has not been comprehensively mapped, presumably by its own proprietors. You shuffle a few metres to the side, and clear blue skies turn to grey. Often the most tantalising part of a street is exactly that part which Google’s cameras have decided not to map, leaving you to leap from one side to the other in hope that some secret between-shot exists. And vast parts of the world have no coverage whatsoever. The only thing you’ll see of China, for instance, are user-installed photographs of heritage sites, with very occasional private restaurants somehow slipped in.

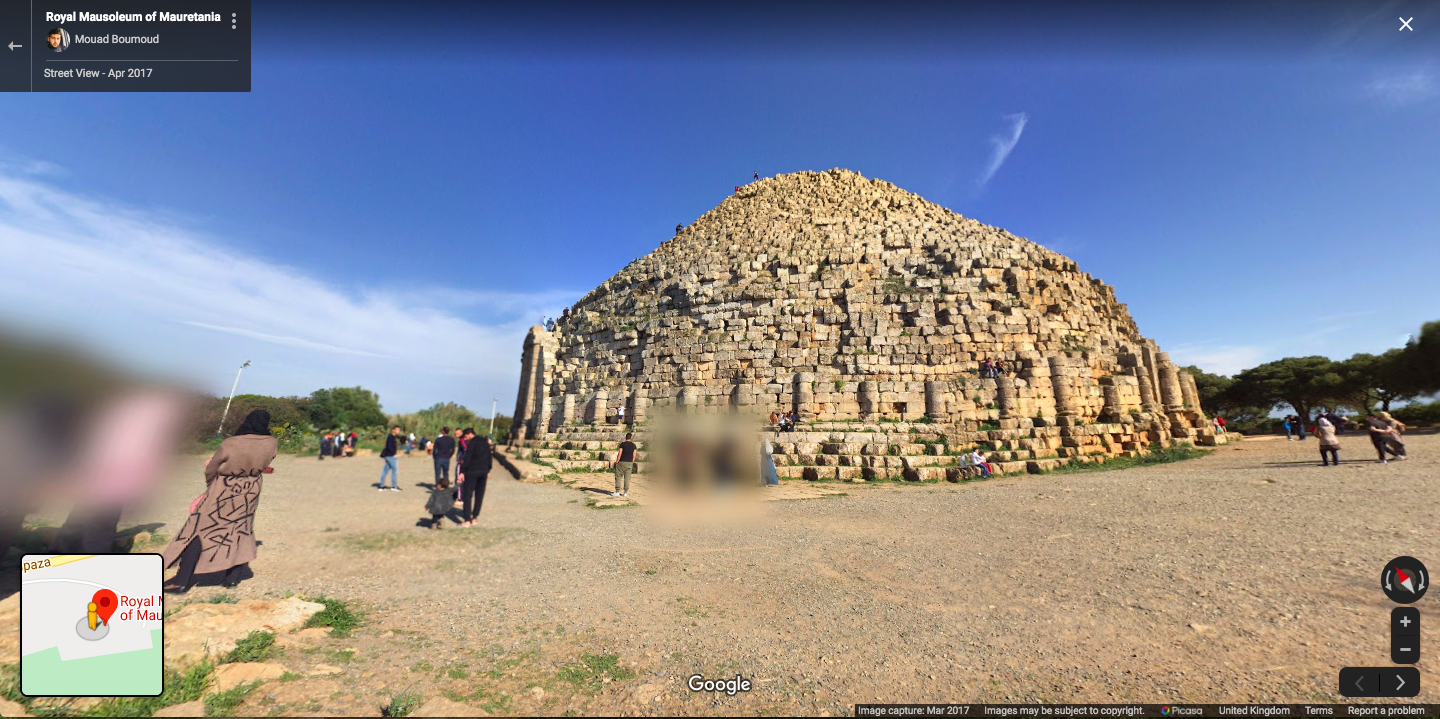

In the places it does fully cover, Street View offers an unprecedented tool for understanding what places actually look like. With a handful of exceptions overrepresented in art and media, the built environment of even global capitals from Mexico City and Mumbai is often elusive to those have not lived in or visited them. Search a city on Google Images, and you’ll get a mixture of wide panoramic views and monuments. But for most of those living in or visiting a city, what actually counts are the things in-between: the workaday buildings, the high streets and residential roads, the transitions between one area and another. This is where Street View excels.

“Doug Rickard repurposed Street View as a medium for documentary photography, a digital echo of the photojournalism of Walker Evans and Robert Frank”

For towns off the standard business and tourist belts, even less is available outside Street View. I particularly enjoy exploring the dozens of small European cities, almost as beautiful as their more well-worn neighbours but for whatever reason barely charted. And rather than deadening my desire to experience them in person, Street View makes me want to experience them with motion, my own eyes and the other senses, to turn them from 2D to reality. The grim corollary, of course, is that one is unlikely to live long enough or have the time and resources to visit more than a fraction of these places. More often than not, Street View is as close as I’ll get. I sometimes wonder if I’ll start to confuse places the I’ve actually been with those I’ve digitally glided through.

In the application’s early years, several artists seized on its potential as a medium. Californian photographer Doug Rickard repurposed Street View as a medium for documentary photography, a digital echo of the photojournalism of Walker Evans and Robert Frank. Jon Rafman’s recently restarted Nine Eyes of Google Maps (2008–ongoing) homes in on oddities, such as a gang of masked children or a burning car. The late Michael Wolf sought similar anomalies, sometimes even ending up using the same images as Rafman.

As interesting as all these projects are, for me they are a little besides the point. I love Street View not for its exceptional ruptures but for its seeming mundanity. I don’t want to use it to tour the Uffizi or Philip Johnson’s Glass House, but for its snapshots of often unexceptional places and people at unexceptional times. The artwork it reminds me of the most is Thomas Struth’s series Unconscious Places, where the German photographer captured cities on his first visit, untainted by prior first-hand experience. By letting you purposefully leap into a new town, a trip on Google Street View might tell you things about a place that an actual journey cannot.