I first met Guillaume Vandame back in 2015. He was sporting gym shorts and a sweatband, shouting things like “I love you! I believe in you! Sweat!” and “Consult your physician!” at me. I’ve come to realise that with Vandame, this sort of hi-NRG opener really isn’t that surprising. These missives were part of a piece he and regular art partner Josh Wright were orchestrating with Monster Chetwynd, an “Insanity Workout” for the ICA’s fig-2 programme. This formidable trio proved to be the instigators of what’s been, hands down, the most joyful art experience I’ve ever had.

Vandame is largely self-taught in the technicalities of art, having focused his studies on art history, which might explain his work’s conceptual core and its frequent textual leanings. People are an equally crucial thread throughout his myriad practice. The works always have a sense of communion and connection; outside of the collaborative Wright & Vandame duo, his independent projects frequently render the viewer an accomplice of sorts, whether through literal participation, or the less demonstrative act of peeling back various layers of narrative and suggestion.

Recurring motifs of language and meaning, interrogating heteronormative histories, social engagement, desire, intimacy and queer identity unite Vandame’s work. Recent projects have included a series of vividly hued canvas prints bearing gestural, expressive representations of his lovers; a series of works and accompanying public exhibition programme inspired by the poet Thom Gunn; a walk through the City of London in which participants became human sculptures in an ambulatory LGBTQI+ flag; and a series of works created with Franks Red Hot Sauce and Durex Lubricant (“a new style of art I am calling non-representational gay art,” says Vandame).

He credits his Long Island upbringing with his ongoing love affair with Abstract Expressionism (and his occasional insistence on being the First Openly Gay Abstract Expressionist). That area was once the site for the studios of De Kooning, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock; and their influence is redolent in Vandame’s approach to colour, conceptual rigour and experimental processes.

“Discrimination and hatred towards gay and queer people has not disappeared, it’s just taken a new form”

- Left: Guillaume Vandame, Kinky AF, 2019. Used pizza boxes and found wood. Right: Homage to the Square (Daniel and Me), 2018, used condom and used pizza box

Your art feels like it always has “you” in it, whether it’s a performance where you’re physically involved, or because of the way you talk through your images with such detail and openness. How do you approach the relationship between you as a person, and the person making the art?

I’ve always tried to have a very holistic vision with the exhibitions I do: it’s not just about experiencing the art within the space, but how to activate that through public programming or something experiential. In the walk I did for Sculpture in the City, I was almost a stand-in for the person who might feel disenfranchised, disconnected, or who lacks a sense of belonging; definitely in the queer community, but also in the world in general. I do think it’s a heightened thing for LGBTQIA+ people, and something codified in our society. There is a sense of disconnect because it’s not completely conventional.

When I began doing projects independently, I started thinking about how to do that within a queer context as maybe more of a personal agenda. There’s an ongoing conversation now around how exhibitions and public programming will change moving forward [in the wake of Covid-19], but simultaneously, the issues related to queer identity are still valid. Things like access to preventative treatments for HIV/Aids or Black Trans Lives Matter haven’t disappeared just because of the pandemic. Discrimination and hatred towards gay and queer people has not disappeared, it’s just taken a new form.

You work across writing, printmaking, drawing, video, text and more. How do you describe what you do, especially in terms of the queer identity that’s at the heart of so much of your work?

I think of myself almost as a gay Pop artist in a way, because some of the issues I’m dealing with as an artist could be seen as archetypally gay. I’m trying to interpret those issues in a way that’s accessible while still maintaining something that’s nuanced and tasteful, or that has the execution of high art. I like thinking about language and meaning: how a symbol, image or cultural artefact changes over time.

On one hand queer culture is debased, or degraded, or “less than”. There’s the sense that it’s abject; it’s the same reason why certain words in gay culture can still be so potent and charged. But being gay is also aspirational. How do you deal with these two conflicting ideas? Someone has described my practice as a form of visual activism, and I would embrace or accept that as well.

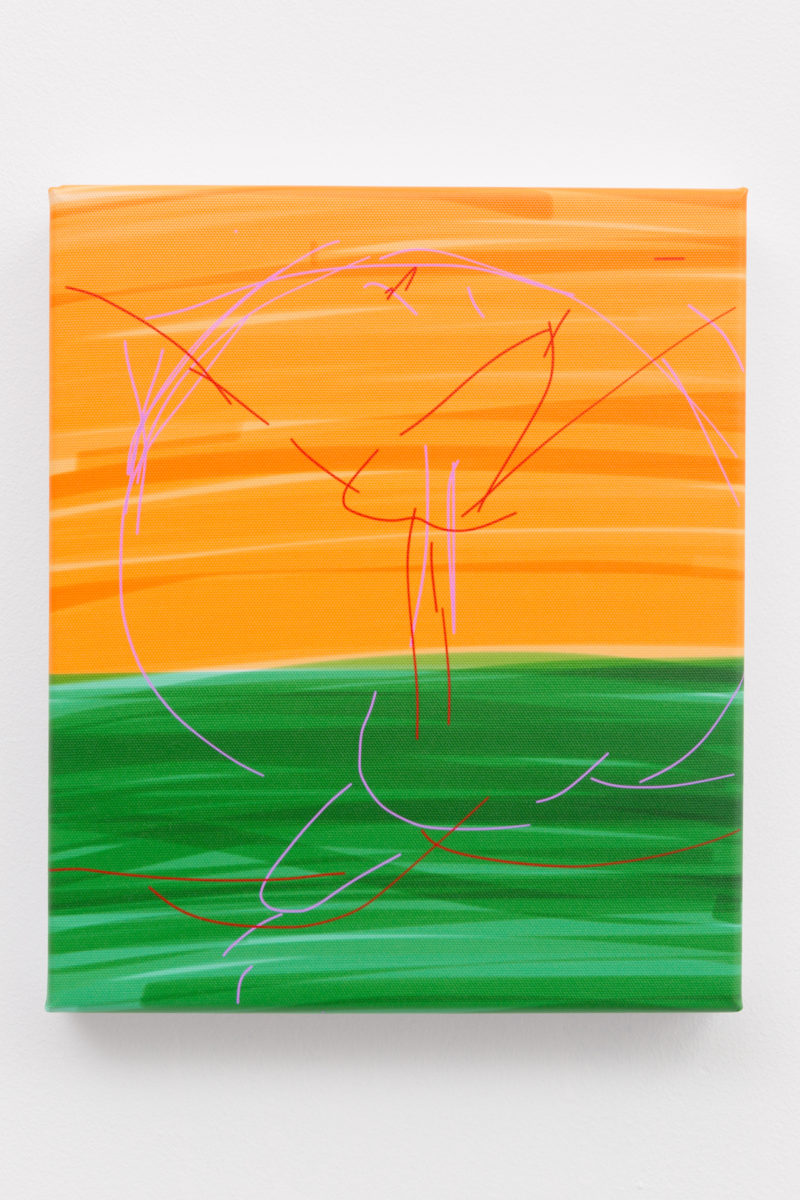

- Guillaume Vandame, Untitled (Lovers), 2018-2019

Do you feel artists have a responsibility to explore politicised ideas?

I think of “queer art” nowadays as two different strands: one is the act of institutional critique, but then at the same time, maybe queer art is just the presence of queer artists in a space, even if it’s not charged. Being queer will always be an act of resistance: a museum presenting queer art is a very political act, even if the subject matter isn’t, because it’s an act of solidarity for those marginalised identities or individuals.

For the same reason, I don’t think I will ever make something that’s conventionally understood as a painting or a sculpture because it will always be marked by a certain kind of otherness. Some people who are queer artists might even say that this is a non-issue, and that they have been able to divorce it successfully. But because I know that there’s so much social injustice in the world, far beyond the Western world’s attitude towards gay people, we still have a mission as a society to protect and defend those rights. It will never be something that we can take as a given.

“Being queer will always be an act of resistance: a museum presenting queer art is a very political act, even if the subject matter isn’t”

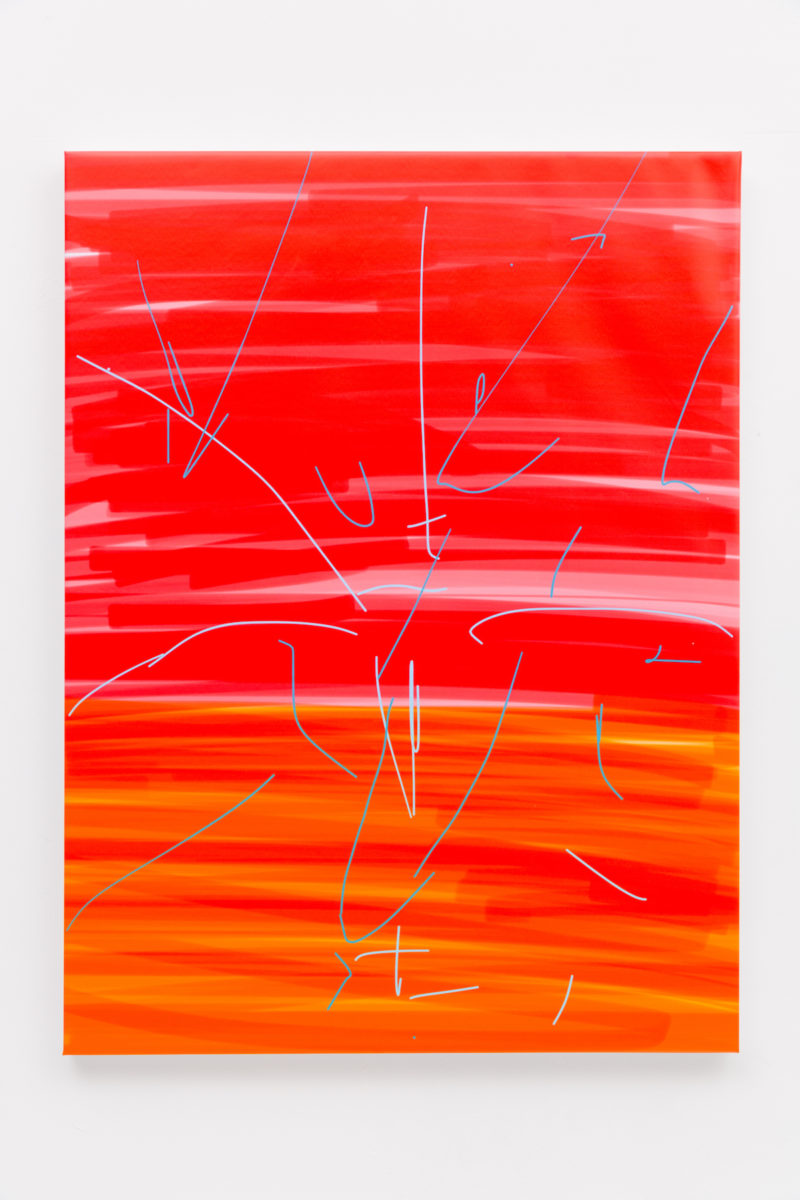

- Guillaume Vandame, Donald and Me, 2018-2019

At your recent SET exhibition, Nightsweats, you were showing some pretty personal works depicting lovers, which you drew on your phone. What’s the story behind those?

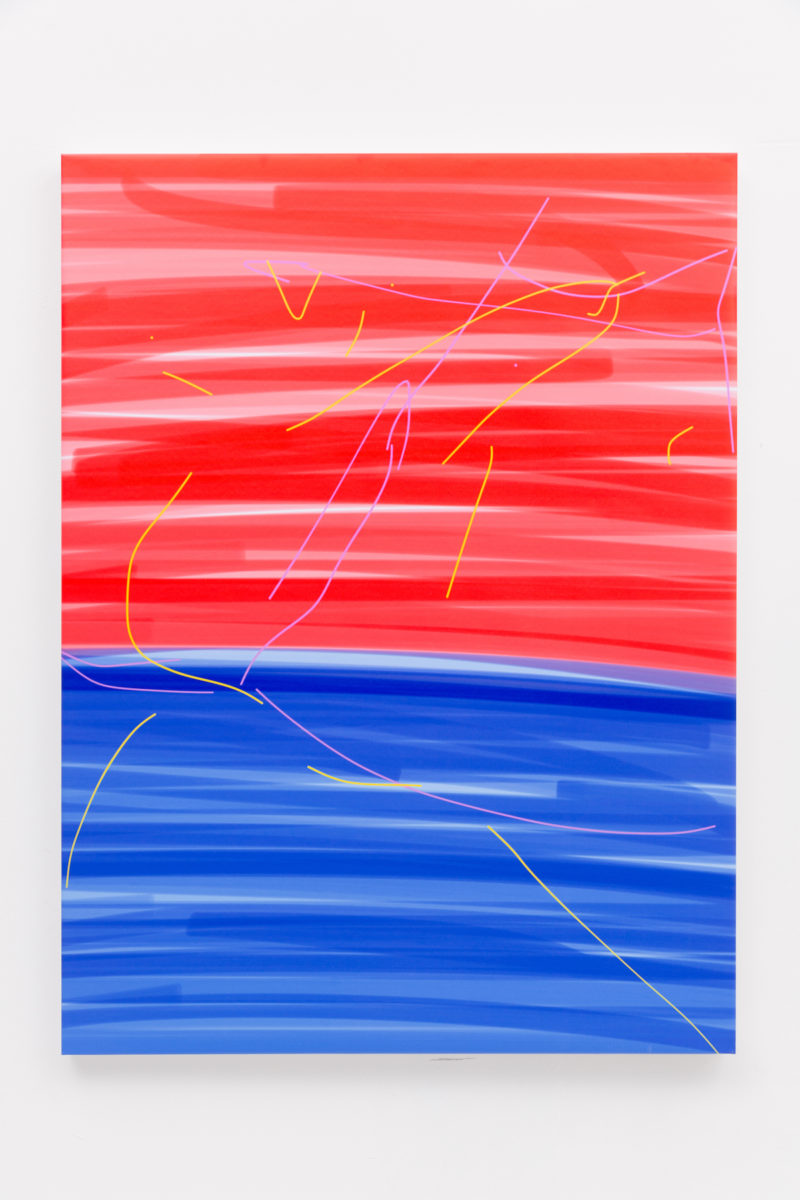

When I started doing the drawings in the spring of 2017, it was a process of trial and error. At the time, I was working on an experimental video essay called love songs, the greatest hits of Celine Dion and Mark Rothko, which consists of a series of video studies of paintings from the Rothko room at Tate Modern juxtaposed with Celine Dion’s music. In between going to and from Tate Modern on the tube, I began making drawings on my phone responding to Rothko. He was able to create seemingly infinite layers of colour through paint, and I realised I could essentially do the same thing on my phone, just adding layers and layers of colour digitally. Originally, the drawings were more abstract, but then I had this eureka moment one day where I thought, “What would happen if I disrupted the colour field with two people? Not just two people, but two men having sex?” The result was instantly gratifying.

I didn’t think I was ever going to publicly show the drawings; they felt almost too intimate. Printing them on canvas as unique artworks felt like a poetic gesture and materialising them in a way that was lost through video. Canvas would be a way of maintaining that sort of quality while also querying it: it would no longer strictly be a colour field, as it would have this queer subject matter. I describe the works as if Mark Rothko and De Kooning had a gay child with an iPhone! More recently, I realised that Rothko also made paintings of people on the subway. A lot of the drawings I was making were on the underground, when I was going from Tate Modern, or from a guy’s house to somewhere else. I always made them afterwards.

- Left: Guillaume Vandame, Kevin and Me, 2018-2019. Centre and right: Joe and Me, 2018-2019

I’m guessing it’s quite emotional to look back on those more personal works. How have your feelings towards them changed over time?

When I look at the works, sometimes I can place a memory or person in the situation. Obviously, I was having sex before I started making the works, so there are other people that were in my mind, but the main guy who inspired the paintings never knew about them. He was a muse but he was also like an anti-muse. I think he would have been dismissive but loved the adoration. There were times when I was completely obsessed with him, and of course, it was completely unrequited. I was so beholden to him, and although if I take a step back I could say “If he’s treating me like this, why would I even bother to engage with him, just stop seeing him,” or whatever, the truth is that it’s so hard to let go. Maybe being slightly secretive about it, or at least not sharing it with him, was a way of trying to cultivate that agency.