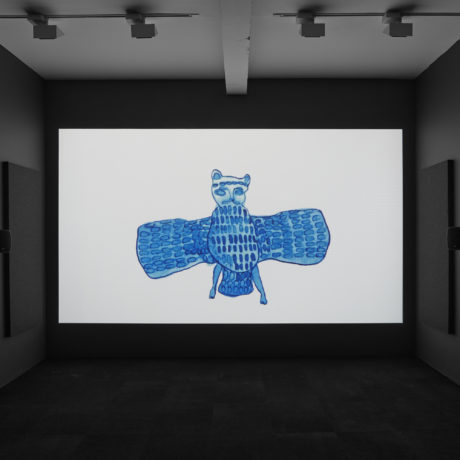

French artist Christine Rebet takes her shoes off to walk into the rooms of her own exhibition. A hand-drawn animation shows the story of the Temple of Eninnu, which was constructed in the twenty-second century BC in ancient Mesopotamia—that covers the majority of Iraq and Kuwait, along with some of Syria, Iran and Turkey in today’s geography—after a god “appeared” to a ruler called Gudea in a dream. Well, that’s how the story goes. Thunderbird (2018) shows a landscape of mountains and puffing geysers which seems to melt into the sand and clay used to build the temple bricks. A soundtrack of a frantic Iraqi oud, which represents the sound of American bombardments and local destruction of cultural sites in recent years, plays from a hidden compartment in the wall. The room itself has only just been constructed, and will stand just two months before it is destroyed. Christine Rebet’s Time Levitation will be the last exhibition in non-profit Parasol unit’s East London space.

- Left: Thunderbird, 2018; Right: Brand Band News, 2005; Both: Installation view of Time Levitation at Parasol unit, London, 2020. Photography by Benjamin Westoby

“Mesopotamians had techniques for being remembered,” Rebet tells me. “In the foundations of Gudea’s temple they buried this.” She shows me an image of a cone covered in glyphs. “The text of Gudea is inscribed on it, and it is also votive. A mini sculpture. If someone digs it up, it will tell them how to rebuild the temple as it was, so that every layer of it put down in the future is exactly the same as in the past. This culture knew that it would decline, that its temples would be destroyed, and at the same time they performed an act of resistance to total destruction. This was part of the civilization: built in. I thought about it as a working image of eternity.”

“We never knew where my father was during the war. We just knew that he disappeared”

After the recent widespread damage of the ancient heritage site Palmyra, Rebet was looking to make a piece about it. “Then I read in the New York Times that the British Museum had found funding for rescue archaeology at various Iraqi sites. I thought, these archeologists are the people making sure that things are eternal. We worked in conjunction: while they excavated the temple, I creatively reanimated the dream that led to its construction.”

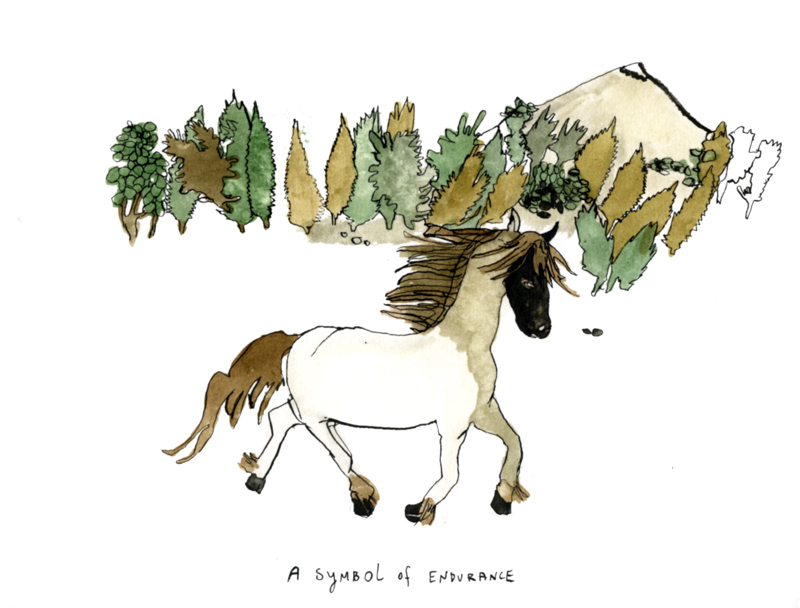

Monk Walk, from Breathe In, Breathe Out, 2019. Ink on paper, 40 x 30 cm. Courtesy the artist

Animation as reanimation. Did Rebet choose to work in the medium because it was always bound to ideas of new life: renewal and even resurrection? “No. I found that part of my mission later. At first it was just natural for me to tell stories. When I started I was fascinated with how the first practitioners used it as an act of resistance. Animation started underground after film, and rose with sound and jazz. Early cartoons were considered subversive. Betty Boop was censored in the 1930s for being too erotic.” The German philosopher and literary critic Walter Benjamin, for one, enjoyed the freedom animation had to comment on anything, being divorced from human actors. He was also worried about the “sadistic fantasies” that were played out. Mickey Mouse and his ilk were “figures of a collective dream”, functioning like “fairytales” and radically symbolizing the lives of those who watched them. The subjects of works in Rebet’s show range from ecological allegory to public protest, the rise of Fascism in the twentieth century and French colonialism.

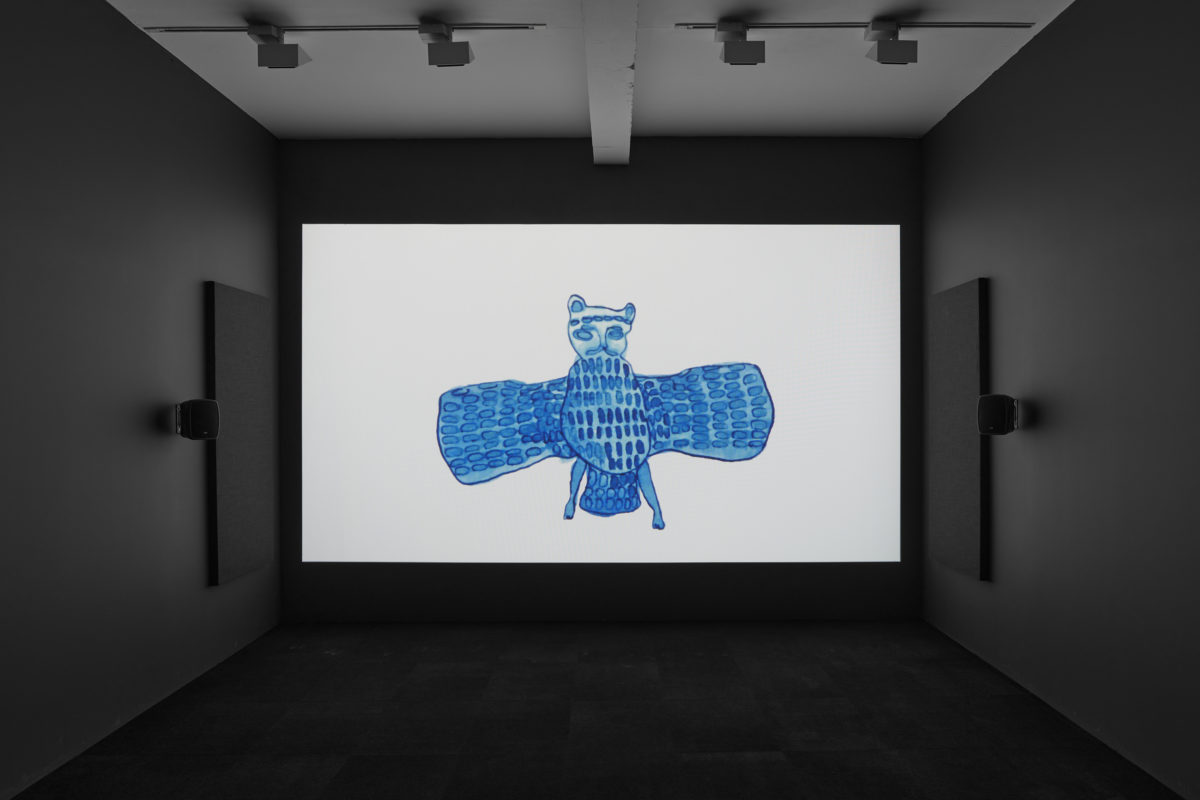

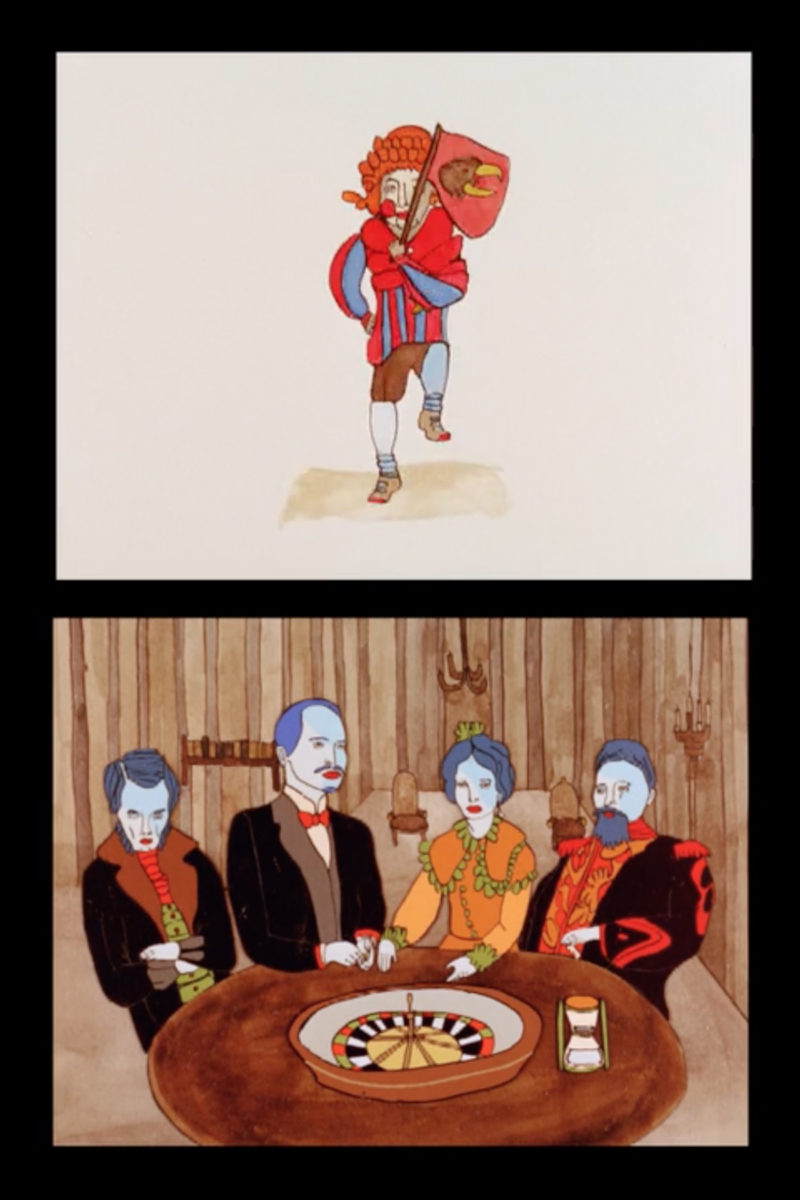

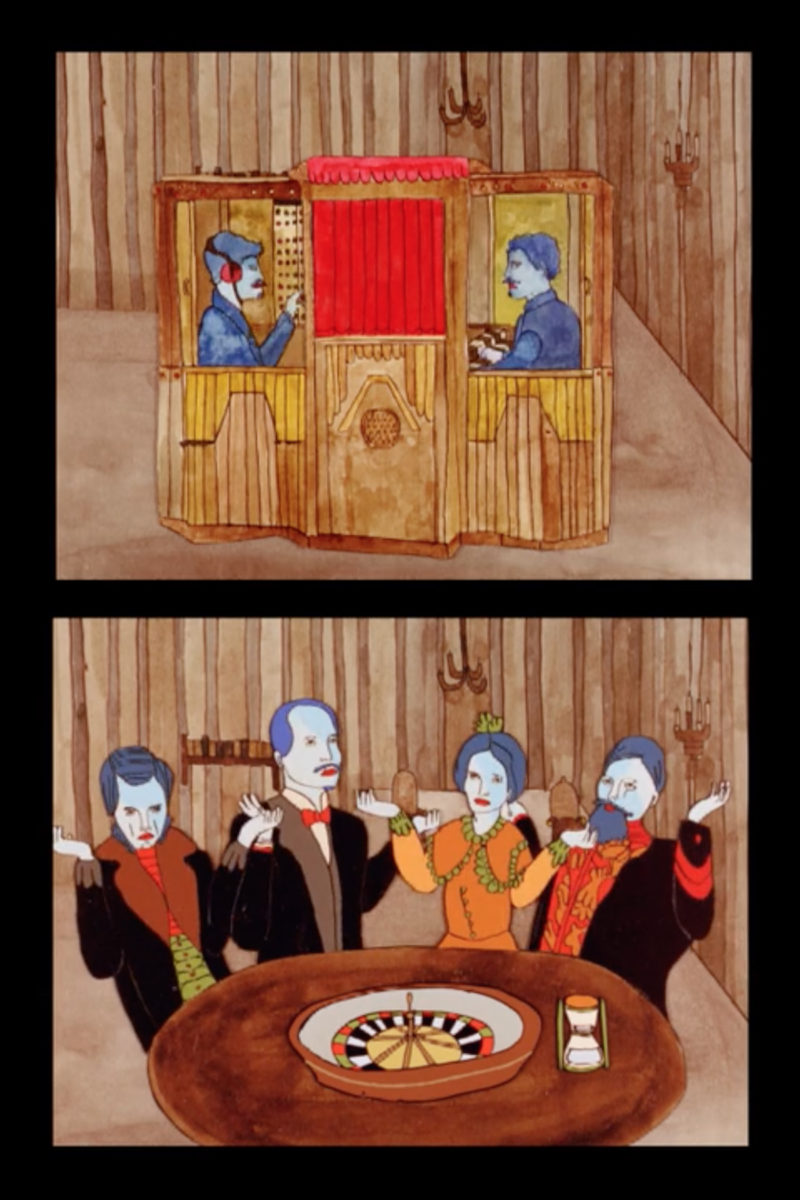

- The Black Cabinet (stills), 2007. Two-channel animation shot on 35mm transferred to HD, sound 3:50 min. Courtesy the artist

Parasol unit first included one of Rebet’s works in a 2007 group show about animation, Momentary Momentum. Now, Time Levitation will be the exhibition on which Parasol unit’s Wharf Road London space ends a fifteen-year run of innovative installation-led shows. Founder Ziba Ardalan tells me it is the resourcefulness of Rebet’s works—created “often with minimal budget, but incredible diligence”—that echoes the outlook of her own gallery space and influenced her choice of final show. “Rebet’s work,” says Ardalan, “apart from constant change as the nature of animation requires, is about renewal and metamorphosis. I find this vision quite refreshing and in many ways it corresponds to my own vision: to always look for renewal. At this very moment when Parasol unit repositions its activities, I think showing Rebet’s work is quite fitting.”

It’s a space that utilizes every hidden nook of its architecture. Over the years here I’ve seen boats suspended in high shafts, and sculpture stretch through the glass to the yard outside. For Rebet’s show, individual screening rooms have been built and decorated to become immersive capsules for viewers. “This aspect was there from the beginning in my work, because I come from theatre,” Rebet tells me. “I’ve always had a space in mind for the work to be shown, a landscape for it.” For the recent work Breathe In, Breathe Out—in which a monk in Thailand undergoes transformations into a range of animals, plants and architecture—viewers can sit on a bench or straw tatami poufs on the gallery floor. For 2007’s The Black Cabinet, which describes a Fin de Siècle seance, the viewing room has been covered in a red damask wallpaper and hung with a crystal chandelier. Victorian chairs have been ordered in. For more austere animations, such as 2015’s In the Soldier’s Head, we are limited to a traditional dark room. (“The theatre of the mind,” Rebet calls it.)

“This culture knew that it would decline, that its temples would be destroyed”

Animation, and the obsessiveness of character it requires, has at times driven Rebet away from the form. “The drawing can take eight months,” she tells me. “You have to do each drawing and there are 3000 of them. So I have to make the process quick for it to stay vivid for me, and to stay engaged. Once you dive into the animation there is less room for creativity. It just becomes something that you suffer. Even psychologically you suffer. You wake up and you have to calculate each drawing for a day. You spend eight months on something which takes two minutes to watch.”

For 2011’s kinetic sculpture The Square, she spent months shuffling four different powders into position around a slab of white plaster for the animation. “After months I broke it. I couldn’t do it anymore. I was fed up. It was responding to Beckett’s television play Quad but that was nine minutes long and I was never going to get through. So I smashed the plaster and made that part of the piece.”

In response to her own working boredom, Rebet also started to look for ways of imbuing the meticulous process of animation itself with abstraction and an element of chance. For In the Soldier’s Head she immersed some of her drawings in water, the degradation mirroring her father’s PTSD after his participation in the French-Algerian War. “I filmed them as they soaked, and I added ink to the water. We shot the drawing being animated, and then the water dissolved the animation because the animation can’t function anymore. It’s also a performance as it happens. I always have to go through a performance. Making and viewing it, you are feeling what it is like to be disappearing. We never knew where my father was during the war. We just knew that he disappeared.”

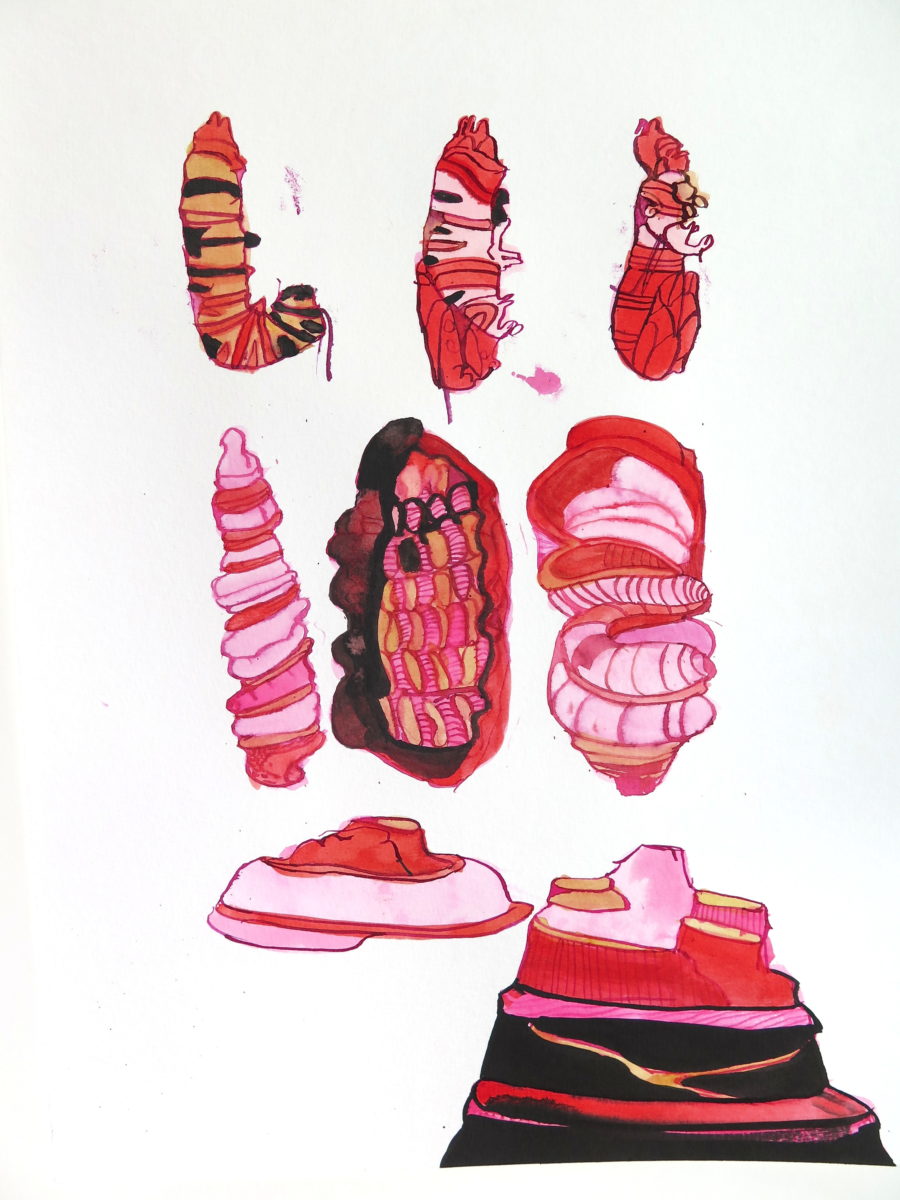

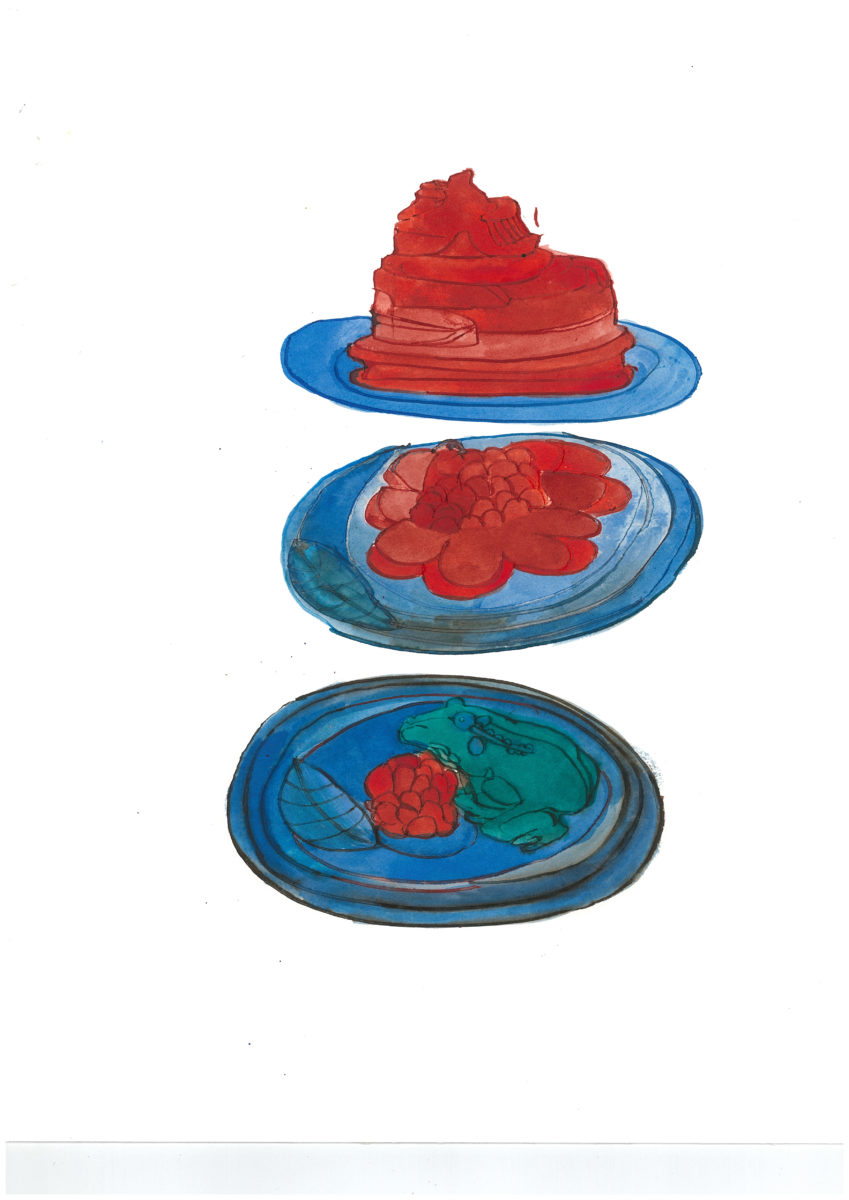

- From left: Tree of Life, 2019. From the series Breathe In, Breathe Out. Ink on paper, 40 x 30 cm; Centre: From Larva to Magic Mountain, 2019. From the series Breathe In, Breathe Out. Ink on paper, 40 x 30 cm; Right: Nénuphar, 2019. From the series Breathe In, Breathe Out. Ink on paper, 40 x 30 cm. All images courtesy the artist

Moving from room to room, we speak about the uncanny and what Rebet describes as “the soul of cinema”: the ancient, flickering effect that can be observed while watching animations. In an age of digital production, where animation can be produced on a computer without drawing each individual frame, does she think the soul of cinema—and animation as an art form—needs saving?

“I think what you can do in the digital age is great. But I am interested in preserving hand-drawn animation for myself because it is my act, my gesture. My gesture is to draw. The magic of the hand. That’s why I like this piece, Thunderbird—because it’s really about construction.” We look to a frame from that film which is hung on the gallery wall. The hands that lay the ancient bricks are drawn. And in the film they will turn into photographed hands in the present, wiping dust off the excavated past. “That’s my mission.”