There are many reasons to be jealous of Peggy Guggenheim (her vast wealth, impeccable taste, her cadre of lovers) but most of all because the art collector and socialite did something most people never will: she touched a Jackson Pollock painting. In fact, she probably touched more modern masterpieces than most people will ever even get to see.

Just watch Peggy in the 2015 documentary Art Addict. Throughout the film, she fondles and pats priceless works as if they were newborn babies in need of love and attention. It seems so natural when she does it, her hands have the firm assuredness of an experienced nurse, as if to say, “They aren’t as fragile as you think”. Yet, the very idea of touching art in a museum feels inherently wrong. Even when we see art that encourages touch, most of us feel reticent and usually end up double checking with the security guard before doing anything.

“Part of Peggy’s genius was that she understood that people get turned on to art by having intimate experiences with it”

It may come as a surprise to learn that “Look, Don’t Touch” wasn’t always the golden rule of museums. European institutions in the 17th and 18th centuries allowed patrons to handle objects. In a paper on museum history, art historian Constance Classen explains that “the curator, as a gracious host, was expected to give information about the collection and offer it up to be touched.”

By the time Peggy was rubbing elbows with the artistic avant-garde of 20th-century Europe, touching art was no longer the norm. With museums and galleries now open to the public, for the most part, the experience became more efficient and less intimate. As a matter of preservation, it was now unfeasible to allow any visitor to touch whatever they pleased.

Does this mean Peggy was selfish, that she acted to feed her own ego through art? It’s true, she touched art because she wanted to, not because the museum culture or even artists encouraged it. However, it is hard to believe that Peggy touched art as a power play. She was a self-described ‘black sheep’ who felt most at home with her art. The actress Mercedes Ruehl, who played her on Broadway, noted that “the only time [she] saw [Peggy] at ease was when she picked up this sculpture by Arp. She was actually happy when she was connecting to the art.”

If you love something, you want to touch it. Tactile feeling is how we experience the world most intimately. Sight, hearing, and smell can observe the world at a distance, but touch requires immediate proximity. The details of an object’s composition (texture, weight, and temperature) all come into focus with touch.

“When you see objects that have been known and handled, you do begin to understand what incremental touch does in the world. It’s about kindness”

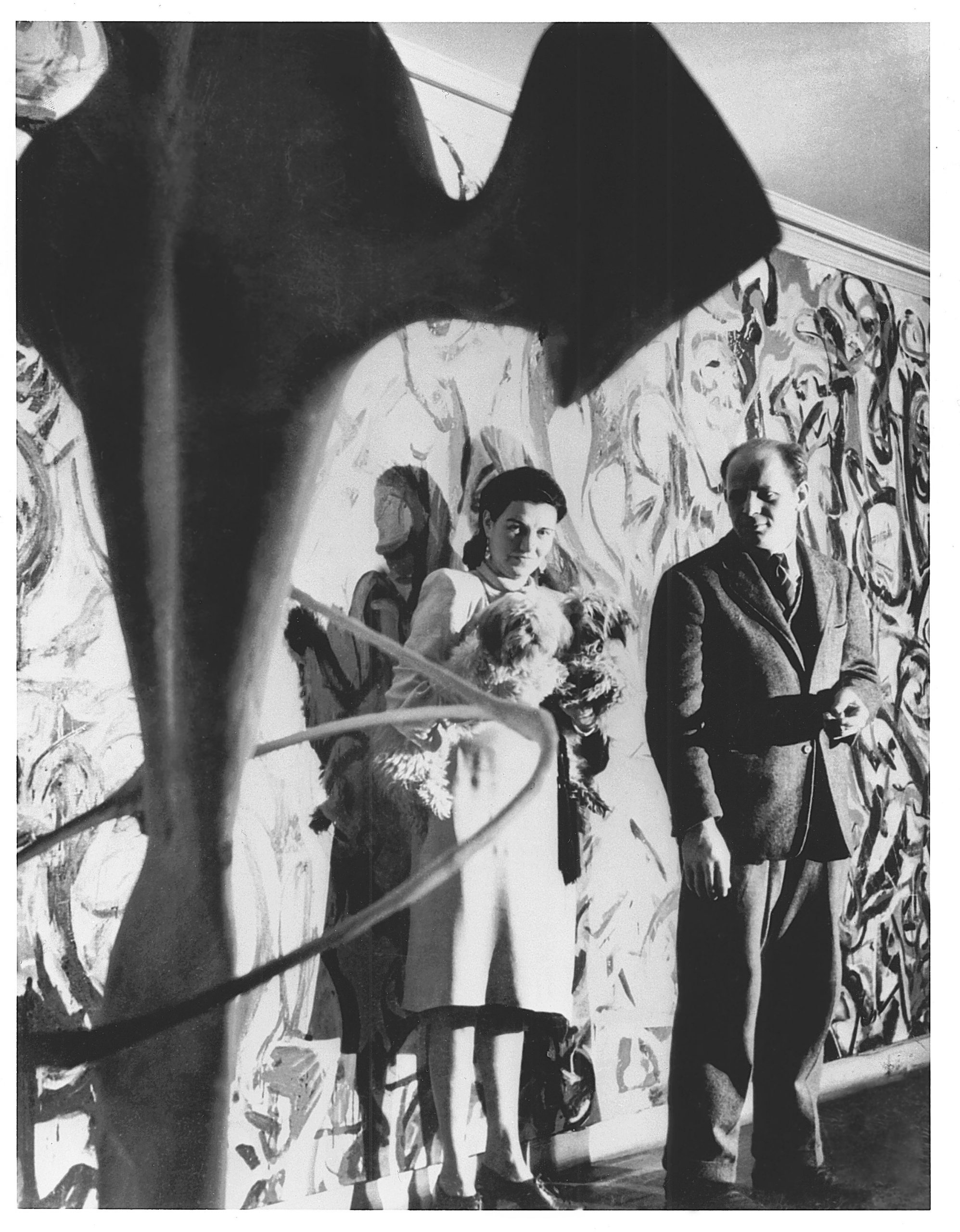

To paraphrase LACMA director Michael Govan, part of Peggy’s genius was that she understood that people get turned on to art by having intimate experiences with it. When she created her NYC space Art of this Century she worked on the design with Friedrich Kiesle, and it was meant to have the intimate feeling of a library. They mounted paintings on poles so the viewer could adjust the work according to the light with the aid of a hand crank. Time magazine described it as a kind of “artistic Coney Island”.

While Peggy was able to create an experimental art space, the role of the modern museum is to ensure its collection is kept safe. So even when artists create work that is meant to be touched, the museum may or may not oblige. Take the 2014 MoMA retrospective of Brazilian painter and installation artist, Lygia Clark, whose work explored the therapeutic possibilities of physically interacting with art. One of the featured sculptures, bichos is a series of steel, aluminium, and gold panels meant to be arranged anew by each viewer. Rather than allow visitors to touch the work, MoMA supplied a replica for people to play with. Preservation was deemed more important than the artist’s intention.

In contrast, visitors to the 2021 Henry Moore retrospective (at the Henry Moore Studio and Gardens in Hertfordshire) were encouraged to touch the work, in line with Moore’s wishes for how his art should be experienced. The curator British artist Edmund de Waal said: “When you see objects that have been known and handled, you do begin to understand what incremental touch does in the world. It’s about kindness. It’s something profound about touch and memory.” For De Waal, the record of touch is a positive addition to the experience of the art over time rather than a danger to its existence.

“The faux pas of ignorantly touching (or even breaking) a piece is something of a pop culture motif”

For Brazilian contemporary artist Ernesto Neto, blurring the lines between art and audience is an important facet of his practice. Viewers are invited to touch and smell his technicolor textile sculpture installations in an all-encompassing sensory experience that recalls Brazilian traditions, including Indigenous practices. “When you think of samba,” he says. “It’s something that you are all doing together. It’s not like the artist is on the stage and the audience is on the ground. When you think about the Indigenous traditions, it’s always inclusive.”

Olafur Eliasson made a similar argument with his 2019 Tate Modern retrospective, which included the installation Moss Wall. This tactile, lichen-covered work changes colour, expands and gives off an odour when watered, reminding visitors that the natural world is far from a static entity. A sign encouraged visitors to touch the piece and experience these textural sensations. As the artist explains, “We have eyes in our fingers too”.

Despite these examples, the idea of touching art in any contemporary setting is still uncommon. One could argue that the “look, don’t touch” policy is as much about separating the artist from the audience and creating something rarefied as it is protecting the work itself. The faux pas of ignorantly touching (or even breaking) a piece is something of a pop culture motif, whether it be a boy who tripped and punched a $1.5 million painting, or Homer Simpson eating the ‘gummi’ Venus de Milo.

The idea of touching art in museums has also become something of a subversive act, with environmental activists using it as a tool to highlight the imminent threat of climate change. Among the slew of recent incidents include a young man disguised as an elderly woman who caked the Mona Lisa (or at least its protective glass), and “just stop oil” activists who glued themselves to a Van Gogh in London’s Courtauld Gallery, before throwing soup at another in the National Gallery. Of the latter incident, British culture minister, Nadine Dorries tweeted that these protestors were “attention seekers” who “aren’t helping anything other than their own selfish egos.”

While no art was harmed in either case, these transgressive acts highlight just how shocking the idea of touching a work of art remains. For now at least, a hands-off policy holds true.

Meridian Payseno is an American writer based in Berlin