The boundaries between art and life are often blurred at the best of times, but as millions around the world settles into isolation for the foreseeable future, the two have come together with alarming ease. Suddenly, the postcards or posters on our walls at home are the only artworks that we might see for months to come, while that particular shade of blue on a wall can start to feel like a mirror to your mood as the days drag on. Short of travelling beyond the four walls of our homes, renovation and re-ordering can become a form of escapism.

For the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark (1920-1988), painting was a way to explore and challenge traditional understandings of two and three-dimensional space. In her redefinition of the relationship between art and life, she sought to give shape to the interior experience that take place within the privacy of the home. A radical pioneer of modernist art, she questioned what art could be, asking how it could act as a tool for accessing sensory memory. “We do everything so automatically that we have forgotten the poignancy of smell, of physical anguish, of tactile sensations of all kinds,” she once said.

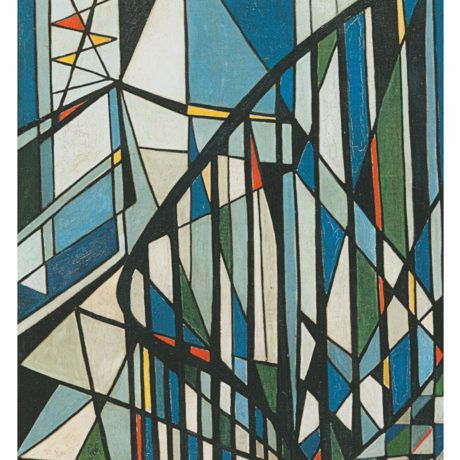

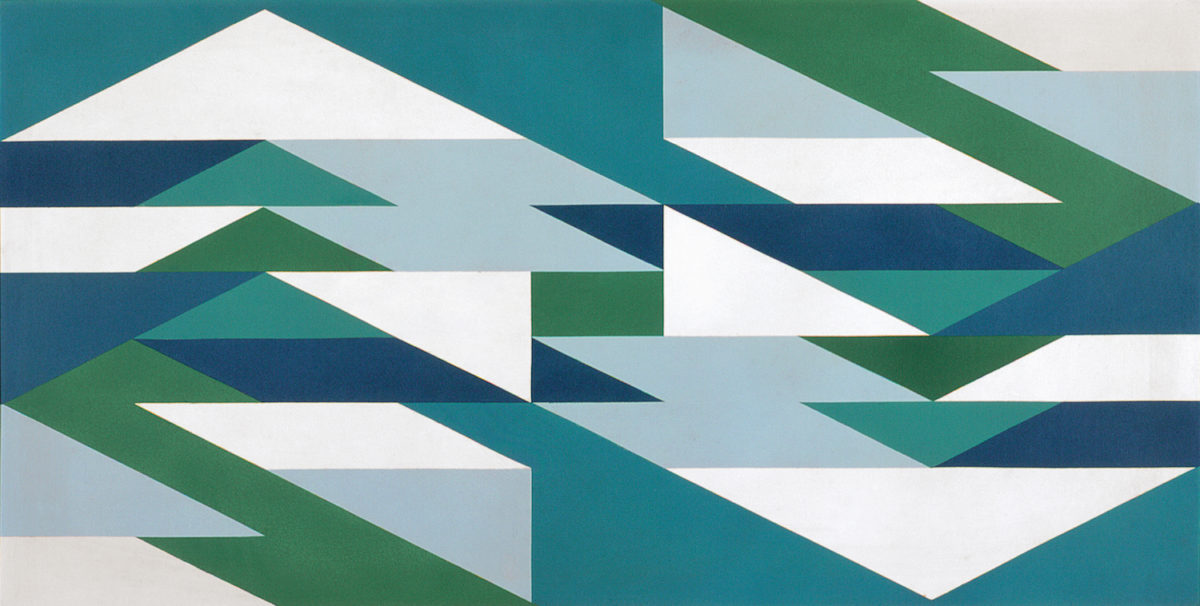

- Left: Modulated Surface, 1957. Collection Ana Eliza and Paulo Setubal. Right: Modulated Surface No. 20, 1956. Fundação Edson Queiroz Collection, Fortaleza

Art and architecture meet in her bold geometric abstractions. She saw painting as an experimental field, where the modulation of space could be expressed through extending the limits of the canvas. Clark spent much of her life in Rio de Janeiro. where she worked as part of the artist collective Grupo Frente alongside fellow avant-garde modernist artists such as Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape. An ardent follower of Piet Mondrian and Fernand Léger, she briefly studied painting under the latter in Paris between 1950 and 1952. Their influence can be seen in the bold colours and patterns of her work, which take an architectonic approach to form and line.

“Short of travelling beyond the four walls of our homes, renovation and re-ordering can become a form of escapism”

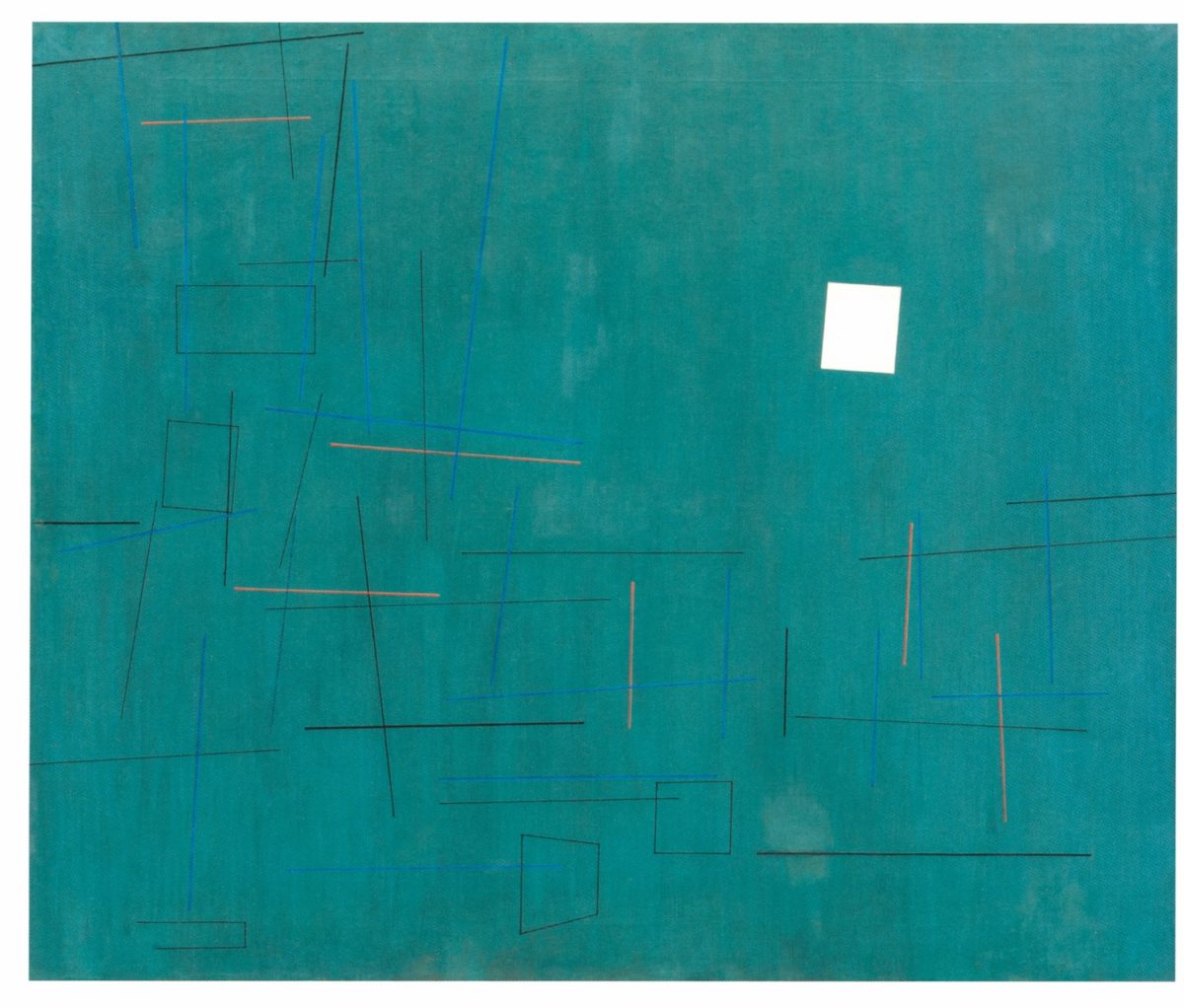

In an early work of Clark’s, she pressed soft graphite to paper in criss-crossing lines until the darkest shadows of these forms appear to almost gleam. Architectural abstraction recurs across her compositions, whether her focus turns to the windows of a church, the cramped space of her own studio or the motif of a flight of stairs. Clark wished to take painting beyond its limits, and set out to create dynamic environments that could “break the frame”. She was interested in the space around her work, and asked how the interior and exterior could connect.

In 1955 she made a series of maquettes, inspired by her teacher Léger who himself had worked with Le Corbusier to create a number of maquettes for his designs. Clark’s tiny imaginary rooms fully embrace her desire to transcend the frame; instead of hanging the painting on the wall, the wall becomes the painting. Here, she set out to fabricate a space where art and life could be navigated and combined in a truly dynamic manner. “What I seek is to compose a space and not compose in it,” she explained.

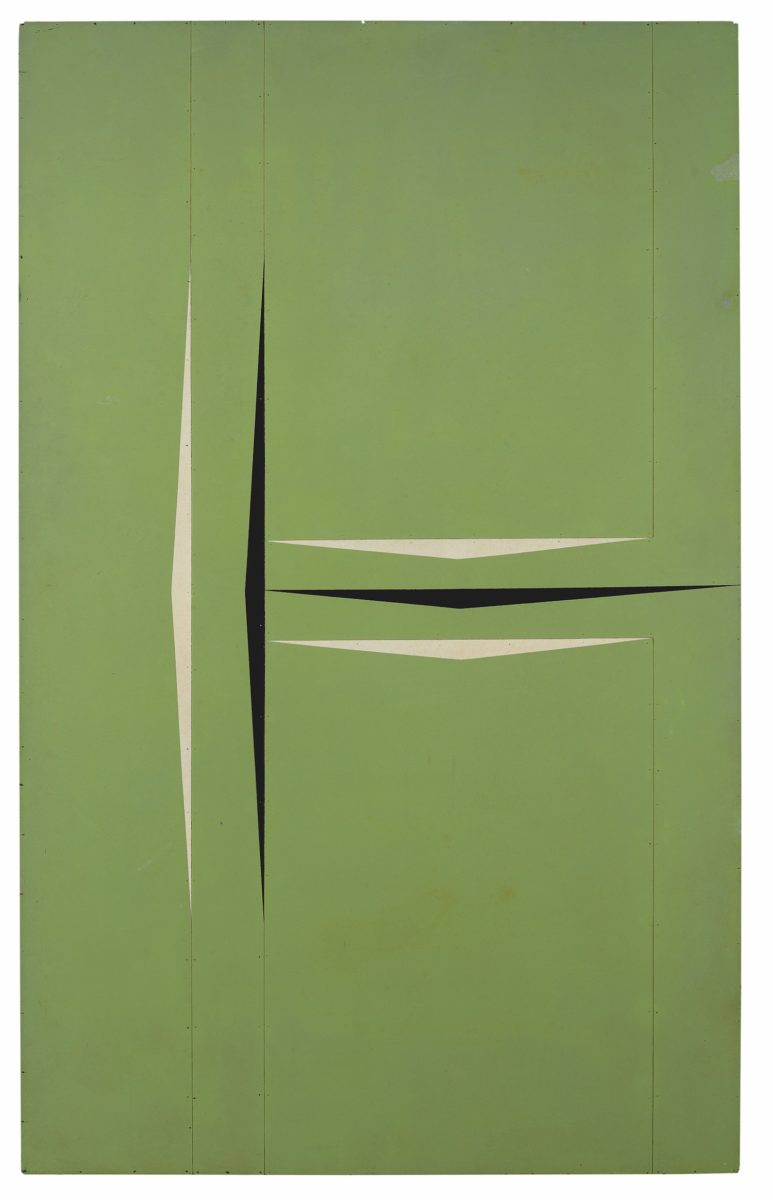

Clark would often construct individual panels before arranging them in her large-scale paintings, creating lines of connection between sections. Through this method, she was able to manipulate the structure of the painting itself and its geometry, enabling these works to become architectural elements within a space. In the latter half of the decade, she abandoned her colourful approach and focused on how she could modulate space and through fundamental monochromatic elements, highlighting the contrast between light and dark.

“Painting is an experimental field,” she stated, and she explored the juxtapositions of space that could be performed within it. It is a poignant phrase, and one that lends itself to the title of the current exhibition at Guggenheim Bilbao dedicated to Clark’s early work. Now closed temporarily due to the Coronavirus restrictions, Clark’s dedication to the creative potential of interior space takes on new meaning, when even a newly-hung picture or freshly-swept kitchen can offer some comfort amidst all the uncertainty. Never have our homes felt so symbolic of our isolated moment.