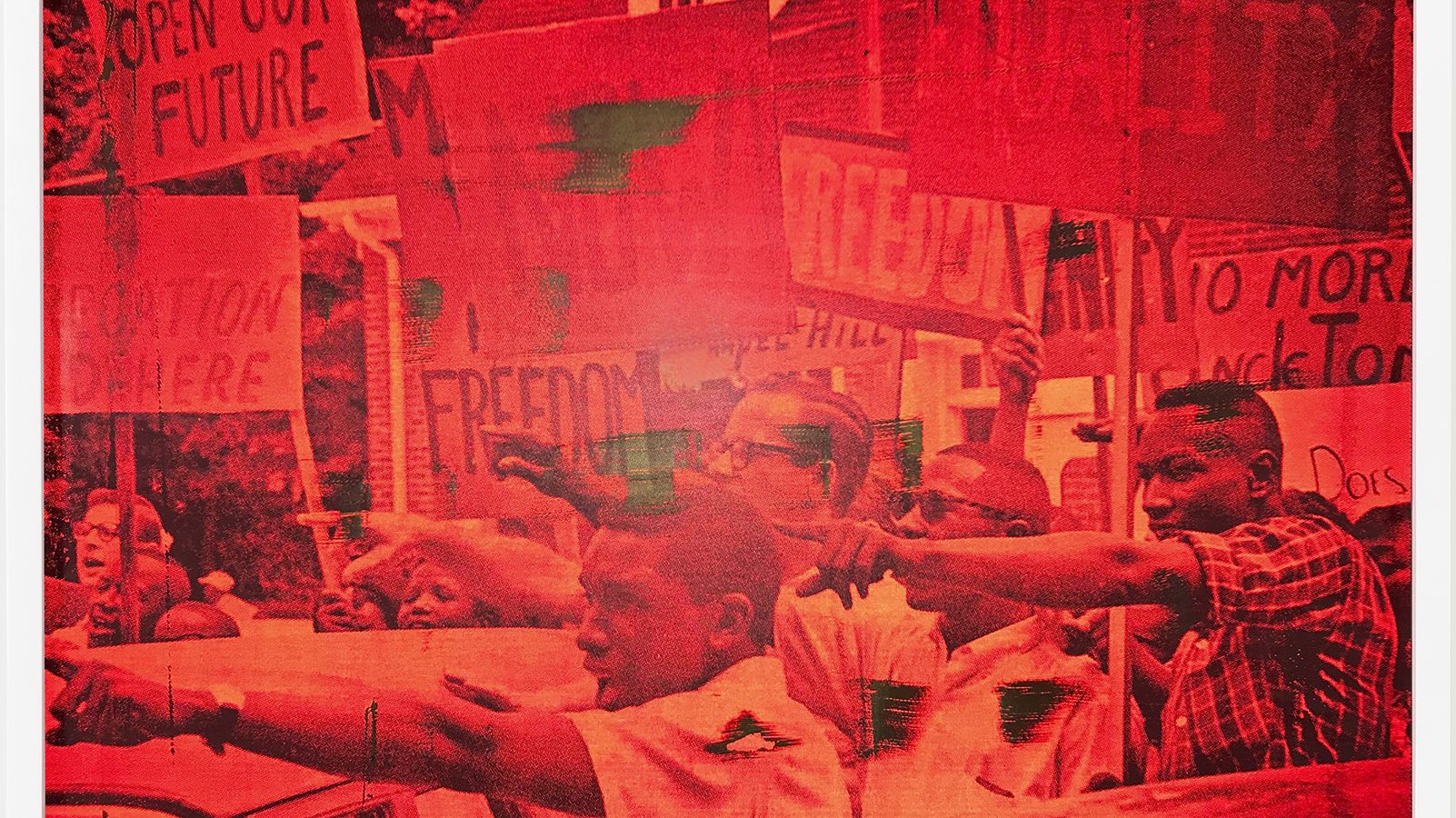

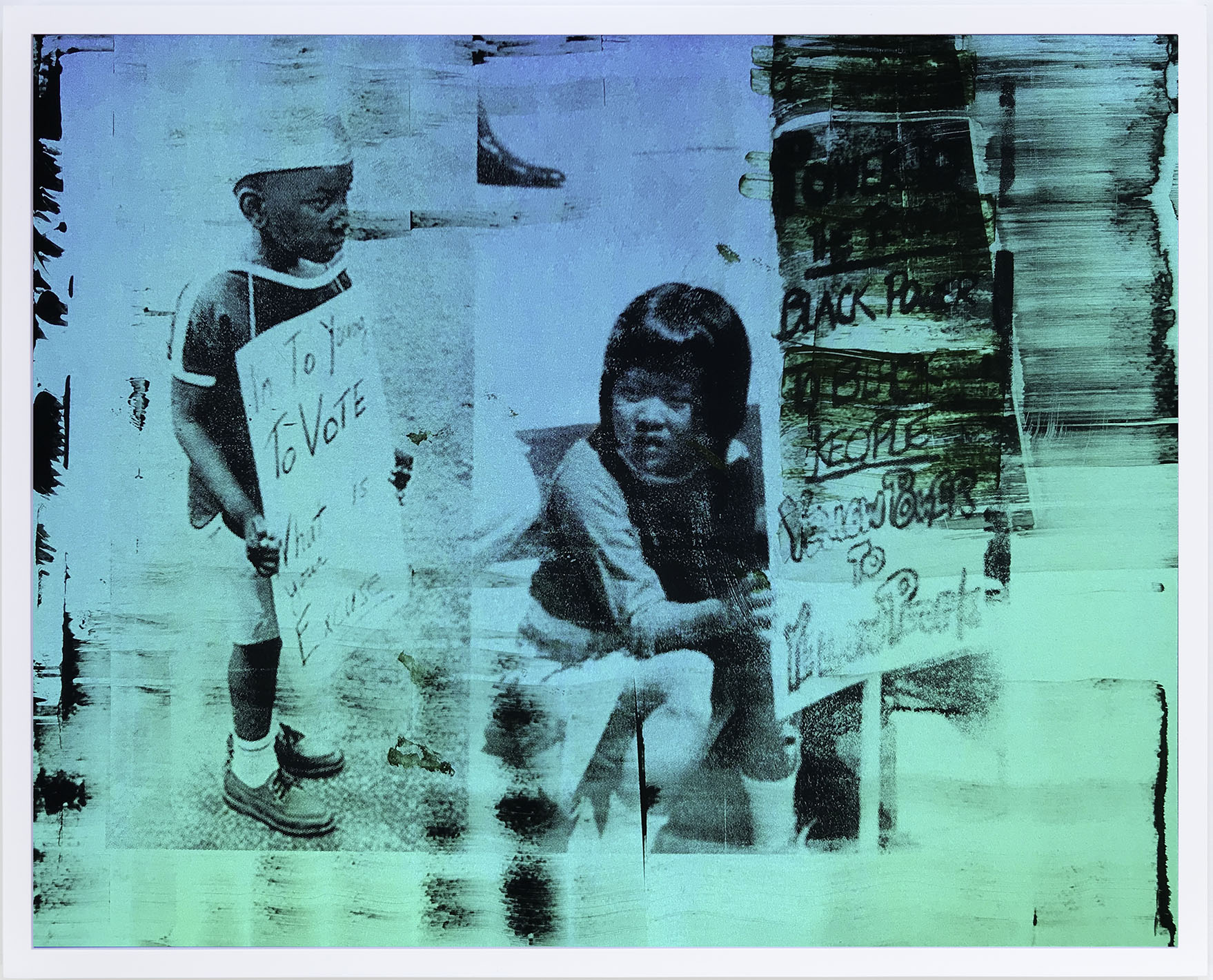

Power to the People I’m too Young to Vote (blue and gold), 2018, (flash)

Hank Willis Thomas is on a constant investigation to understand how we perceive the imagery and communications that surround us, and the myriad ways that differences in race, gender and social status impact those reactions. He has doctored advertisements to highlight representations (and stereotypes) around identity, invited a broad public to air their views in The Truth Booth and collaborated (through the artist super PAC For Freedoms) on a billboard that combined an image of the civil rights march in Selma in 1965 with the contemporary political slogan “Make America Great Again”.

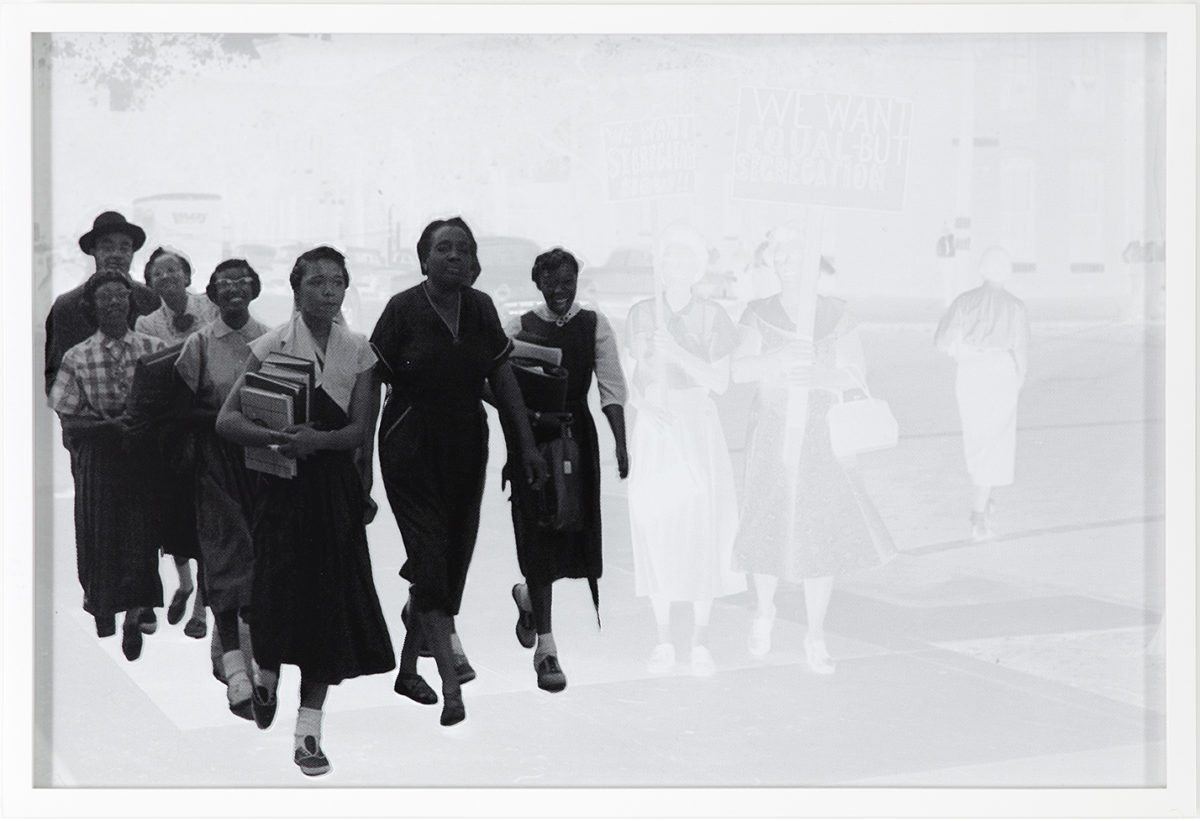

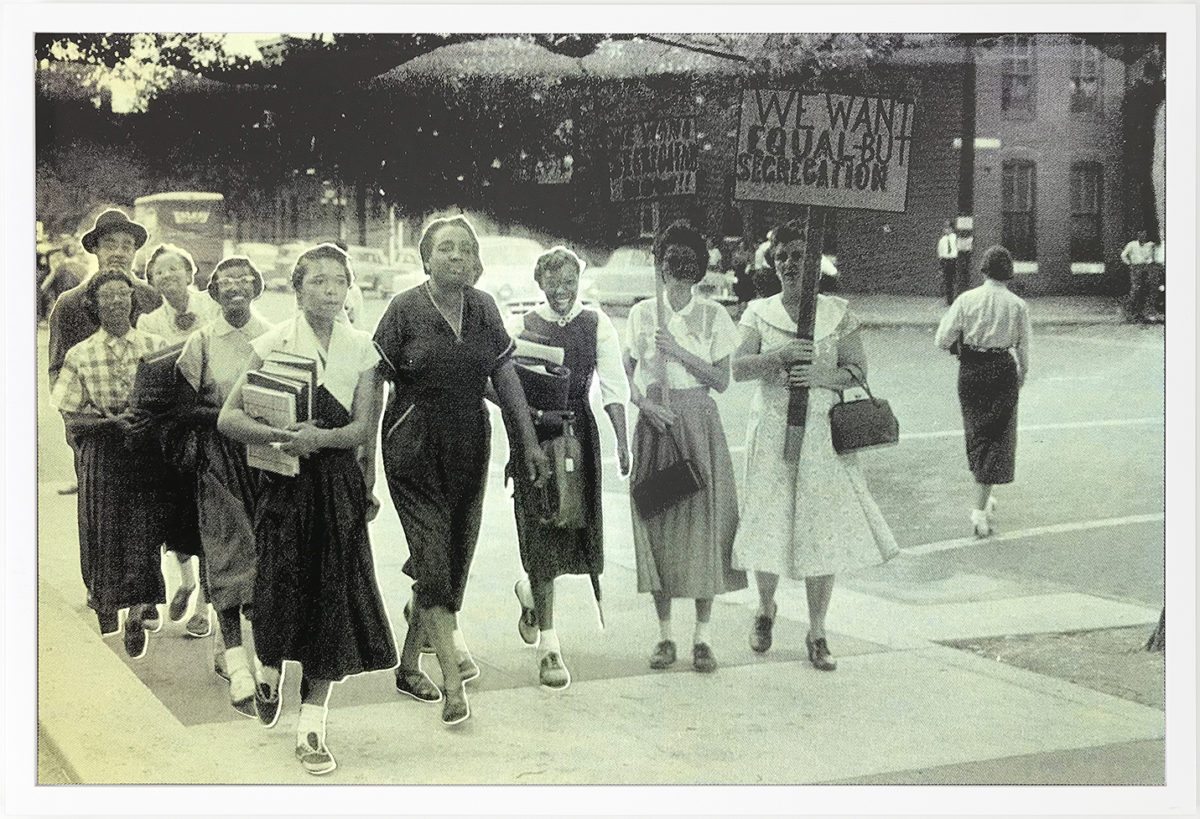

In his new show at Jack Shainman in New York, he has used utilitarian, reflective materials to present archival protest images that have varying levels of visibility, depending on the viewer’s interaction with them. Many are “activated” by using a flashlight or the viewfinder of a smart phone, which suddenly reveals the wider context of the action taking place.

You are using a very specific reflective material in many of the works on display. What is its significance?

The show is a different journey for me because I’m primarily using one material. There’s a retroreflective screen, which is rarely used in fine art. It’s an industrial material used for “stop” signs and to make other forms of public wayfinding. I’m trying to use it as a method to illuminate images, stories and parts of history that are often overlooked or have become so lost in the landscape of hyper-consumption of photography, through mediums like Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. These limit our capacity to actually look closely, because we’re trained to scroll past, and we’re constantly trying to discover the next best thing.

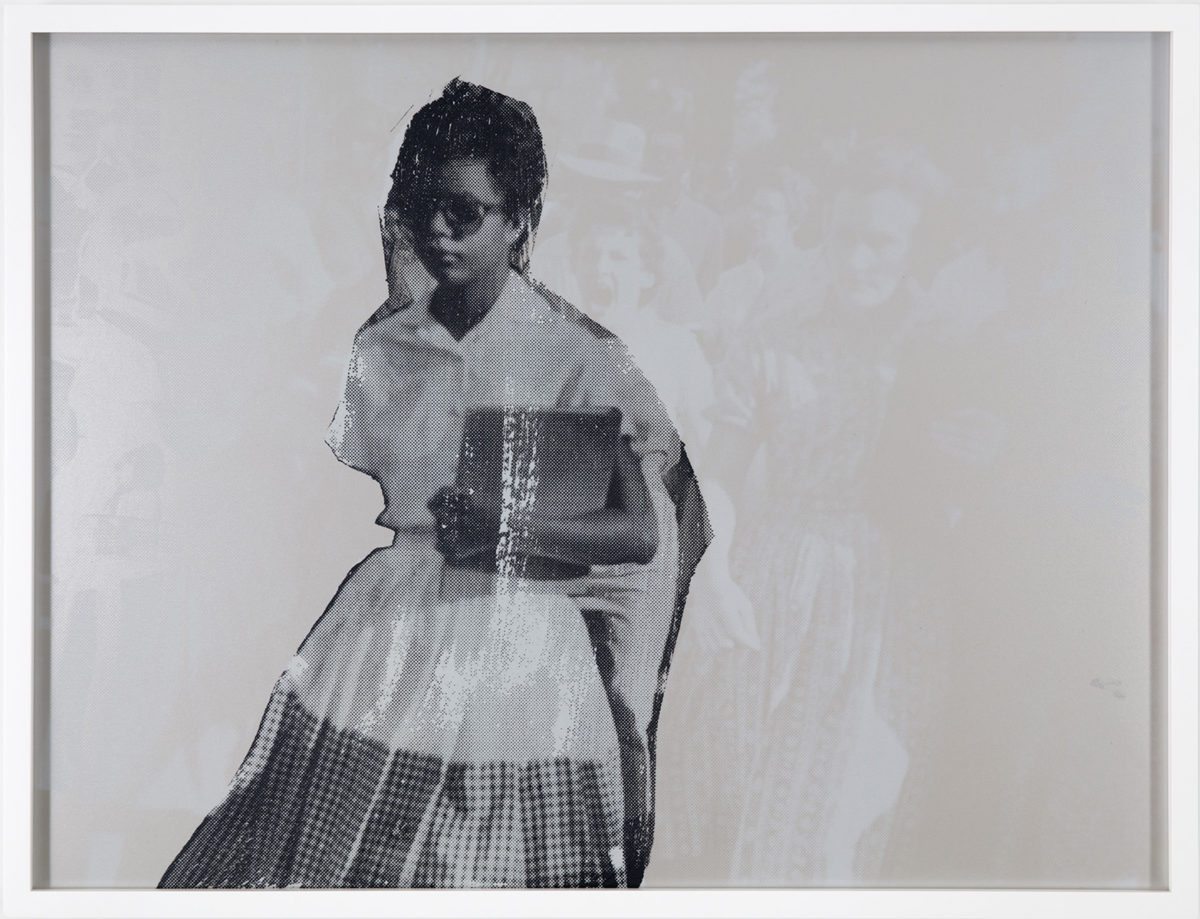

- I Tried to see a friendly face, 2018 (no flash)

- I Tried to see a friendly face, 2018, (flash)

The show is an opportunity for provocation; for myself and viewers to pause; to reflect and to see things in a new way and maybe discover things we should have seen. A lot of images are about protest, mostly in the United States and around civil rights. I was trying to connect them to a greater narrative of the past.

It’s the kind of work that, even when you’re looking with your own eyes, you wonder, “Am I really seeing it?” The work demands that the viewer moves around in order to see it. For example in photographs of Turbulence, which features an image surrounded by gold, it would almost never look like that to the naked eye. It would only look that way if you were staring at it with the sunlight right behind you, or with a flash.

The way that you view the work in person, with all these different ways of seeing, seems so prescient at this point in time. We need to be so careful about the information we are digesting.

Yes, for sure. I’ve always been interested in framing and context and how depending on where you stand it affects your notion of the truth and reality. You can see that in other work that has been discussed by Elephant, like Unbranded: A Century of White Women. Also, the Truth Booth project, where it’s really about how, by removing one small element, you can actually reveal an underlying truth. I’m really interested in both me and the viewers becoming investigators and explorers; helping to create a greater curiosity about the information we’re getting, how we get it, and how we react to it. It’s about not taking anything at face value. We’re also in a period of political rhetoric that relies heavily on slogans and advertising methodology.

That’s a tried and true strategy in politics. Just look at the Third Reich, that was all about branding and getting people to buy into a notion about themselves and the world. If we think about Volkswagen, that’s a product of Nazism. It was designed as “the people’s wagon”, and we think about [the car] as apolitical, as a product. But it’s the product of a political regime’s branding strategy.

“There were times when photographs were especially revered, because of the unique perspective that they gave us on life.”

Have you worked with existing protest images from your archive for this show?

Yes, I’ve worked with a couple of the images before, but they’re all brand new pieces. I have a constantly growing archive. I’m a photographer and a photo historian, so that research has been an important element of my life from before I can really remember. It is a form of navigation and making sense of the world. Photographs are often seen to document our representations of the truth. They can also challenge these ideas.

- We want equal - but...(II), 2018, (no flash)

- We want equal - but...(II),, 2018 (flash)

It seems like we’re also making our own truths, through live-streaming events or otherwise documenting actions that might not otherwise be seen. There’s an element of that, in the fact that people need to view your work through a device, in order to experience all of its different facets.

Correct; how do we see again? There were times when photographs were especially revered, because of the unique perspective that they gave us on life. We could pontificate and learn about ourselves and the world. I guess I’m trying to reawaken that––the revelatory feeling.

It almost looks as if something has been physically wiped away from some of the images you have used as if it is being uncovered. Is there deliberately more noise and texture?

I’d say some of them, not most of them, are more painterly. There are more mirror works in this show as well, and a stainless-steel sculpture. So, you could argue that the entire show is about reflection. It takes a different effort, working in the more painterly way. But maybe doing that calls attention to the manipulation that is going on by me, the relationship with the photographer, and the medium itself.

Freedom Now (red and gold), 2018, (flash)

I think the concept for the show is actually really simple. It’s about the ongoing, perpetual and never-ending quest for equal rights. The weed is constantly growing. One of my catchphrases is, “The road to progress is always under construction.” We’re always trying to reach this plateau where we think everything will be okay and we’ll all be on equal footing; that justice will be served. But every time we get there we realise that these people were left out or forgotten, that they weren’t part of the calculation. I think the question is: “What is it that we want, what does equality look like, and what does that mean in the future?”

Hank Willis Thomas: What We Ask Is Simple

Until 12 May at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

VISIT WEBSITE