Modern life can feel like an intolerable, deafening cacophony, pummelling us from screens, leaking across paper-thin apartment walls, screeching through metal train carriages, rattling insomniac minds. It’s little wonder that so many turn to twenty-first century #mindfulness—ancient wisdoms neatly reformatted for tinny phone earbuds and cutesy sans-serif fonts—to help drown out the sounds.

But there’s a reason we sing lullabies to small, pre-verbal sound-gurglers, and that certain songs are often the most resonant emblems of a time, place or first love. And as people are becoming more open to practices such as yoga and meditation, sound therapy is booming. Alternative healer Louise Shiels attributes this partly to sound healing’s passivity. “It’s just about ‘receiving’,” she says. “Sound baths aren’t necessarily an aural experience, because you’re not always actively listening—it’s the body taking in these frequencies and vibrations.”

Cafe OTO, London

The profundity of sound isn’t just down to fripperies like childhood memories, folkloric tradition, indie-disco nostalgia or even its modern-day meditative properties. Sound and brain chemistry are so intertwined that we often ignore the everyday terminology that spells it out: take beta-blockers (medication used to manage heart conditions and anxiety), for instance. Wave and brain frequencies are measured in hertz (Hz), and fall into five categories: gamma (40-100 Hz), involved in higher-process cognitive functions like learning and memory; beta (12- 40 Hz), which help focus and stimulate our waking minds (caffeine increases beta activity, beta-blockers lower it); alpha (8-12 Hz), which bridge the gap between conscious and subconsciousness, and aid relaxation; theta (4-8 Hz), involved in daydreaming, sleep, creativity and emotional connections; and delta (0-4 Hz), associated with the deepest levels of relaxation and restorative sleep.

“The more I’ve played the gong or bowls, the more layered and polyrhythmic my music production has become”

As such, sound can directly shift our brains from one state to another: it can calm, arouse and even heighten creativity. This power has long been explored by musician Janine A’Bear and her audio-visual artist partner, Steven McInerney. Both recently trained as gong practitioners, and they explore the fundamental properties of sound frequencies and vibrations daily in multifarious ways: in healing contexts for others and for their own mental wellbeing, in art-making, and by exploring the more nebulous capacity of sound to alter the subconscious.

“I had thought that [my music-making and gong healing] were quite separate, but now I play gong for myself every morning and then sit down and make music, or experiment,” says A’Bear. “The more I’ve played the gong or bowls, the more layered and polyrhythmic my music production has become. They’ve definitely influenced the way my brain thinks when I’m programming beats.”

While McInerney first explored gongs purely through an interest in their musicality, he’s seen their effects “creep into” his own compositions. “With the film side of what I do there’s always been a psycho-spiritual connection, exploring altered states of consciousness. I don’t know if the gong space has influenced that or the other way round, but I’ve seen a natural process.”

Aïsha Devi’s music similarly works with the healing powers of sound frequencies and delivers them to club spaces. Her practice deliberately sites music in opposition to what she has termed the “parasitic” quotidian frequencies of devices like phones, computers and even fridges—and the way corporate culture subliminally uses music to provoke consumerist desires.

Her deployment of music in healing and ritual spaces draws from the Eastern spirituality of her Nepalese-Tibetan ancestry—Vedic Hindu texts, metaphysics and her personal meditation, from which she developed her technique of harnessing specific variations in vocal vibrations. Learning from Tibetan monk rituals, she’s described combining multiple oscillations and poly-harmonies with the frequencies of her music to potentialize sound’s impact on not just our minds, but our physical organs, cells and DNA.

Devi sees such ways of working with sound, most notably binaural frequencies (those which denote a difference between what we hear in the right and left ear), as analogous to narcotics—a way to “escape physicality” through inducing the state of supra-consciousness (transcendence of individual consciousness towards a universal one). Her work, then, goes way beyond the “hypnotic” descriptor beloved of music journalese and instead strives for both dissolution of ego and of boundaries between the “real” and the metaphysical.

- Steven McInerney, Singing Bowls

In 2015, composer Max Richter worked with a neuroscientist to create Sleep, an eight-and-a-half-hour, night- long concept album, or “personal lullaby for a frenetic world and a manifesto for a slower pace of existence”, as he put it. Sleep’s release was accompanied by listening sessions in which the audience was given beds for the night: for one, Richter and other musicians performed the entire piece live (setting two Guinness World Records for both the longest live and longest radio broadcast of a single piece of music). When I went to a Sleep playback event—a pyjama party of sorts on a shop floor—the experience was profound. Listening back to the record, I realized that I’d heard less than ten minutes of it, instead dozing into the longest snooze I’d had in years. Maybe that was its scientific alchemy; maybe, too, it’s the product of listening with a rare intensity and purpose.

The art of listening as a key to understanding not just music, but the world around us, is pivotal for many in creating an order of sorts in mental chaos. Pioneering musician and composer Pauline Oliveros developed “deep listening” in 1988, when she and two other musicians improvised on their instruments in a cistern fourteen feet underground. “We had to respect the sounds that came from the walls and had to include it in our music sensibility,” Oliveros has said. “To hear is the physical means that enables perception; to listen is to give attention to what is perceived both acoustically and psychologically.”

“Deep listening” evolved from a playful pun to a serious artistic concern, and Oliveros went on to found the Deep Listening Institute, which aims to “strive for a heightened consciousness of the world of sound and the sound of the world”.

While Oliveros has never been a direct influence on the work of London-based artist and musician Beatrice Dillon, it’s not hard to see parallels between cistern-delving and Dillon’s 2017 project Taut Line, shown at AND Festival and Somerset House in a cave and underground tunnels respectively. Inspired by the history of rope-making at the Peak Cavern site and the “physiological or mystical qualities of sound + bass + emptiness as perfected in Jamaican Dub music”, Dillon says, this multichannel sound installation used six oscillating sine waves running at different pitches, speeds and volumes in a dark, subterranean context. The six individual note strands eventually interlock into a single chord (a minor eleventh, typically found in gospel); with the sound shaped by the space itself and where the listener was situated within it at a particular time.

“Sound baths aren’t necessarily an aural experience, because you’re not always actively listening”

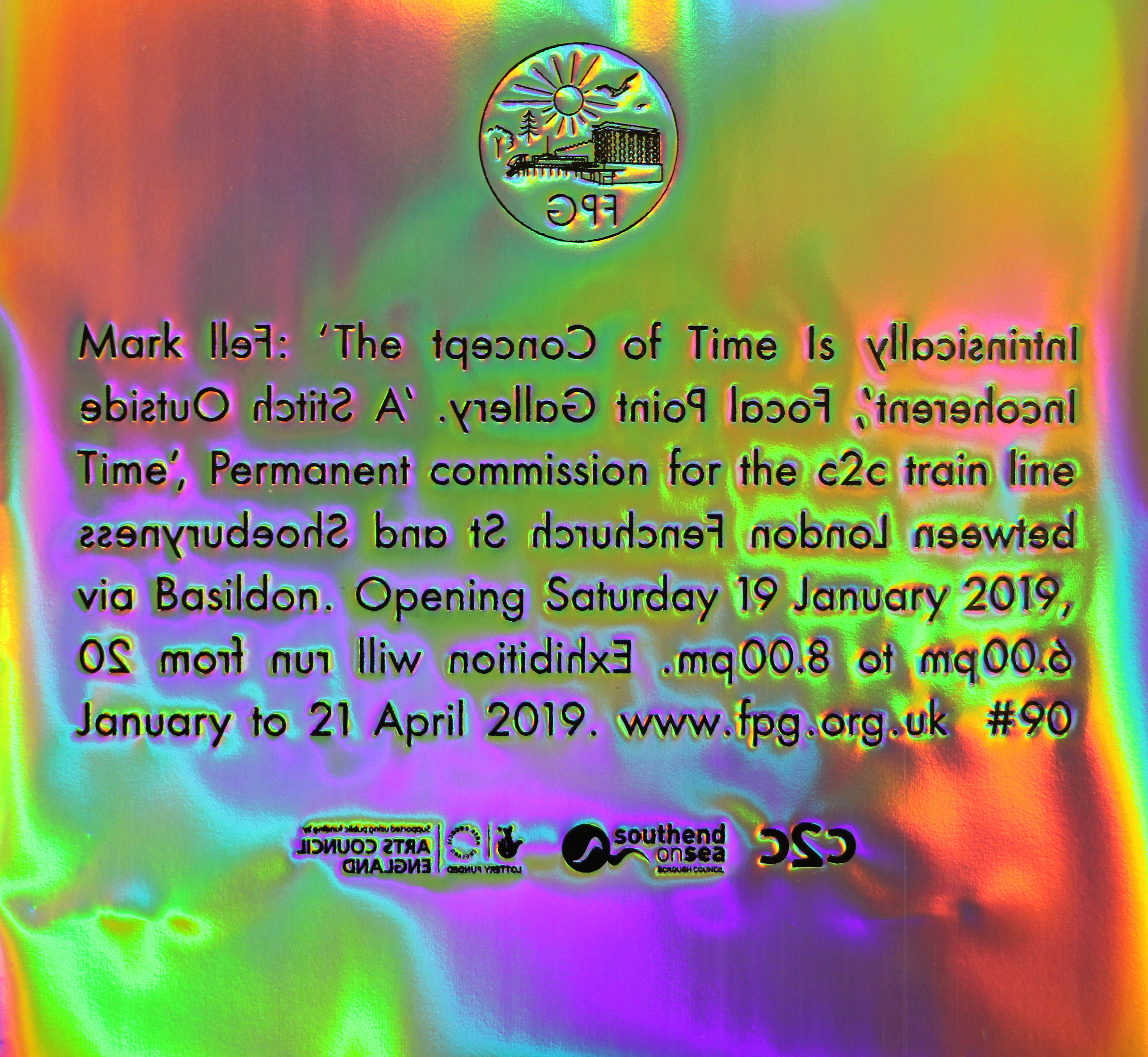

Time, again, was at the fore in music producer and artist Mark Fell’s app, A Stitch Outside Time, an ever-evolving sound composition developed in collaboration with artist Rian Treanor and developer Peter Worth, alongside Fell’s show at Focal Point Gallery in Southend. Designed for passengers on the c2c train line running between London and Southend, the app uses generative music technology that simultaneously responds to the train’s movement and the user’s location, meaning the exact same piece of music is never repeated. Here, sound becomes an integral manifestation of how we physically situate ourselves in the world—in that it responds to location and motion—but also how we place ourselves there more esoterically. For many daily c2c users, the experience is perfunctory, often frustrating and occasionally unpleasant. Fell’s piece takes this commute and makes art of it; it makes us listen to the journey itself through the datasets it creates, and the potential for them to become music.

Perhaps, then, we should fixate less on solipsistically shutting out the world’s noise and more on truly, wholly listening. Listening is a mysterious, profound art that’s unique to each of us. Gloriously, though, it’s also part of a loftier connected cultural experience on an imperceptible level. “Whether it’s chanting ‘om’ or singing a football chant, you’re using voices to create a certain vibration: they’re different ways of doing the same thing,” says A’Bear. “No one can deny that the influence of sound to change the way you feel is immense.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 40

BUY ISSUE 40