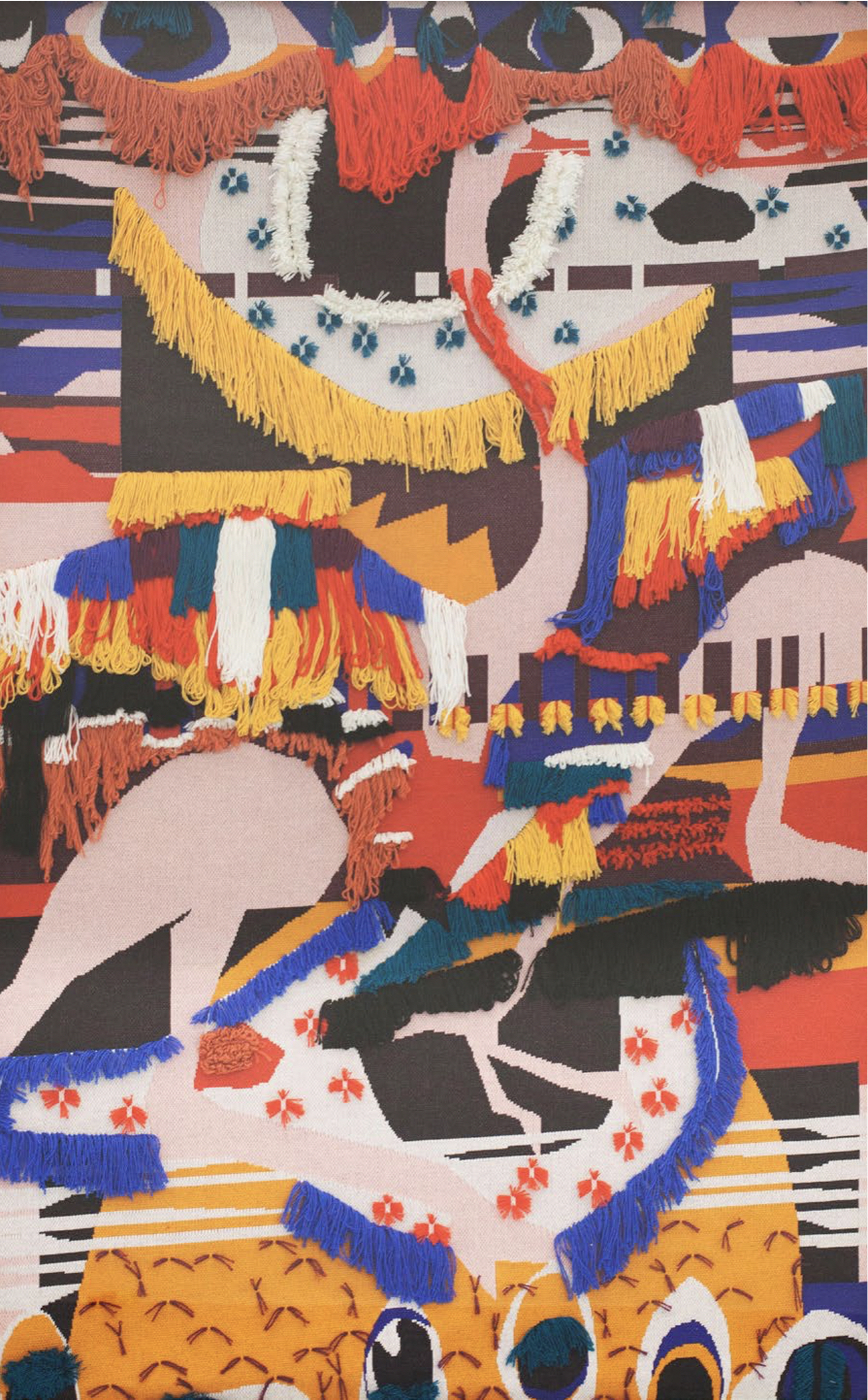

Henrik Vibskov has a neat way of summarizing his sprawling creative life. “I am a multidisciplinary person who works with textiles,” he says. Those textiles can be hanging on a gallery wall, paraded down a Paris catwalk or adorning the set of an opera or dance production. They are on sale at Vibskov’s boutiques in New York and Copenhagen. At a stretch, you could also point to the textile skins that Vibskov beat for seven years as drummer in the electronic music combo Trentemøller. “I’m sorry, I’m a little bit difficult to put in a box,” the designer says (let’s call him a designer). “That’s super-annoying, I know.”

Many believed Vibskov’s return to Denmark in 2001 following his reputation-forming studies at Central Saint Martins would signal a retreat. But despite establishing Copenhagen as his base, Vibskov has never been far from the spiritual epicentre of the fashion world. He is the only Scandinavian to be offered a yearly show at Paris Fashion Week and is a member of the Chambre Syndicale de la Mode Masculine. In 2011 he became a laureate of the Söderberg Prize, the highest accolade for a designer in the Nordic region.

Vibskov’s varied creative pursuits are intriguingly intertwined. Depending on your vantage point, his photographs shift in tint and texture like samples of billowing fabric. His music has its own sturdy weave and careful colour control. But as his catwalk shows have become more conceptual and theatrical, so galleries, opera houses and dance companies have lured him into more abstract but traditional creativity. In the first half of 2017 he has a major solo exhibition in Paris, a performance at the MAD museum in NYC, serves as curator at Mindcraft (the Danish pavilion) at the Salone Mobile in Milan while his designs will be seen in Madama Butterfly at the La Monnaie opera house in Brussels and in the Norwegian Ballet’s Swan Lake at the Théâtre du Champs-Elysées in Paris.

When we meet at his workshop on Copenhagen’s industro-chic Paper Island, Vibskov is preparing for the imminent opening of his third solo exhibition at Ruttkowski;68 in Cologne. The exhibition’s centrepiece will be forty-eight over-sized spinning tops made from oak and ash, and painted in a bright but tightly controlled scheme of pinks, yellows, reds and blacks. As if to emphasize the fact that everything in his creative life is connected, Vibskov points to the origins of the idea: a series of smaller spinners used decoratively in the tiny café he runs next door.

The spinning tops neatly encapsulate one of the most ignored but consistent features of Vibskov’s work: his sense of control and his respect for form. The shapes themselves are varied but stray minimally from the toy’s established geometry. Their paintwork, applied by hand, is highly considered (“I decided to add this turquoise quite late on,” Vibskov says, pointing to a tiny band of greenish-blue on one object).

A few years back he did something similar: taking Børge Mogensen’s “No 1” sofa and other chairs—sacrosanct design classics in Denmark—reupholstering them with his own colours, symbols and textures but leaving the physical design intact. Critics have pointed to Vibskov’s resolute stance outside the minimalist Scandinavian design tradition and its dogmatic principles, but in truth his work has started to reveal that tradition’s magnetic pull. His treatment of Mogensen’s furniture adumbrated that idea; if anything, Vibskov is becoming more and more Nordic.

There is something very tangible about a lot of your work in wood. The pieces want you to touch them.

We’ve tried to base a lot of the works on the same methods or processes we use for handcrafts, textiles and fibres; the ways of working are related. So if you want to touch it or feel them, I’m cool with that.

“The mind is good at adapting to the environment it’s in, like a chameleon”

Some of your stick work—in particular, these protruding wooden sticks that form something like a pointillist surface with their tips—could almost be textiles.

I have references from my education and background in textiles but I try to respect each material on its own terms. It’s not that I look at a wood piece and think of it as a textile piece. But it’s certainly connected to experimenting, which can produce surprising results. A lot of the preparation for the Ruttkowski show has simply been looking at what’s around—picking stuff up, like the spinners from the café. We never have much time, but the result is that it’s a little more direct and intuitive.

You talk of depth in your work, but not so much of discipline, which is clearly important—your view of form and your setting of parameters.

I grew up in the Danish countryside. So I’m aesthetically educated in our history of design and craft—without knowing it, in a sense. So, yes, I’m “controlled” in a Danish way, but I’m also from the countryside where everything doesn’t look all organized as it does in the city. I am Danish, but in other ways I’m not really Danish.

Does your aesthetic outlook change when you’re in New York?

I find the mind is good at adapting to the environment it’s in, like a chameleon. People are adapting their styles and so on, using coded signals, deciding how to appear. You quickly see that those people in New York who look the same are people who are doing the same work. If I was hanging out there longer I probably would too.

Would you be freer there? There are critics in Europe who only focus on the playful edge in your work.

I’ve been referred to as a gøgler [literally, “performer”]—a sort of clown, someone who stands and juggles. I really hate that word because that’s not what I’m doing. People writing from a conservative northern European point of view—British and Scandinavian—see the colours I use and that’s the best they can think of. In that sense, yes, it really depends on where you come from and where you’re working. To someone working in celebrity menswear, of course I look like a clown. But if you’re in Africa, maybe it’s not so clownish. I do think there are many layers to what I do: political, cultural, religious.

“I was sitting there and I thought: hey, maybe we should only do dance stuff, only work in that field!”

How do you reconcile those layers with the commercial imperatives of the fashion world?

It can be super-annoying. I’ve been doing music for thirty-four years, and that has many similarities with the textile business: you need a viewer, you need someone to come to the concert, you need sales agents and fairs. The human behaviour is similar: the hype, the pushing. The problem for me as an artist is that some people see my work in fashion and for some reason they believe it devalues my other creative works, which I think is a shame. It’s the other way round, I think. People are kind of “oh yeah, he does fashion, he’s not a real artist”.

Surely it works both ways? The fashion world might credit you with a little more gravitas and therefore afford you more freedom.

That’s true. Sometimes I feel I should just go one hundred per cent one or the other, but these days it’s much more common to be multidisciplinary. It has opened up. Fifteen years ago it was like, “no, you can’t come to this place, because you come from the wrong area”.

Were you schizophrenic about it in your own mind?

Not really. I was perhaps more engaged; engaged with energy to try other things. In the fashion world it can be quite dictatorial: that runway has to look like that, this has to be in this position. Perhaps it made me try other things and say, “No, let’s hang some bird necks down” [the show Necks Plus Ultra], and try all sorts of weird things.

Now that you’re collaborating more and more with stage directors, is that ability to act on impulse more constrained?

I’m pretty easy-going. I’m cool with someone else having control. But I know if I had full freedom it would be better. Sometimes I’ve been working on a project where they’re like, “Hey, just do what you want”, and then we’ve built it up from there. That’s a much better process for me than a director or a lighting designer steering me. But whatever you’re doing you never have one hundred per cent freedom. Budgets, materials, the space…

Will you be working more in theatre?

Yes. Dance in particular. We did costumes for a dance piece in Austria recently, and the company [Ingri Fiksdal

] took the costumes as the starting point. We had a dialogue and stuff, but we delivered the costumes and they then decided what they could do with them—how they could move in them. So it was choreographed later on. That was a pretty wild experience. I was sitting there and I thought: Hey, maybe we should only do dance stuff, only work in that field! But the theatre world is old and institutional. I don’t have time to sit in a room for three months and watch endless rehearsals. But something like that dance show really gets you thinking about the possibilities. There are so many.

This feature originally appeared in issue 30

BUY ISSUE 30