It’s been a busy week in Germany. Straight off the back of Gallery Weekend Berlin, a few days packed full of openings, beer, cigarettes and not enough sleep, I find myself on the four-hour train ride to Bavaria’s capital for Public Art Munich (PAM). In a more leisurely fashion than Berlin’s frenzied and tightly-packed single weekend of openings, PAM runs from April through to late July, with “performances, interventions, public gatherings, talks, aperitifs and much more” taking place every weekend.

The title of PAM this year is Game Changers. Curated by Joanna Warsza, the happening brings together over twenty artists including Alexandra Pirici, Ari Benjamin Meyers, Jonas Lund and Julieta Aranda. Each artist has been assigned a site, which had or has the potential of becoming a “game changer”, with a focus on Munich’s political past and present, which has been punctuated by moments such as the 1919 proclamation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, the Olympic Stadium’s 1972 inauguration and the 2015 welcoming of refugees into the central train station. Over the course of the forty-eight-hour opening, the Munich public and the visiting art tourists are calmly navigated across the city to witness five performative acts, a welcome break to the often harried, trolley-dash nature of biennales and public art events.

Opening the trail is Aleksandra Wasilkowska’s Gold for Natascha, Silver for Timofei. Walking to the piece through woodland paths we enter a small sanctuary, which is woven through with spring blossoms, and are greeted by smiling women serving lemon tea—there is an almost cultish kitsch to the place. At the foot of the path is a rather lopsided building complete with three wavy spires, and something that could potentially be regarded as a Christian cross heads the main tower. On entering the building we’re sucked into another world, a garbled audio scripture, akin to a film script created by John Waters and Ryan Trecartin, is played backwards, filling the room, which is loaded with candles, Hello Kitty stickers and images of a multitude of gods, goddesses and religious icons. The ceiling is covered in glistening silver foil.

This is my first encounter with storytelling and mythmaking in Munich. In the gardens of this beautiful poly-church, I am told various, slightly different versions of stories by keen locals and agents of PAM about how an “exiled Russian hermit” and his wife, Timofei and Natascha, illegally constructed the “East-West Peace Church” in the mid-1950s, and covered the ceiling with chocolate wrappers, giving asylum to those in need. According to some tales, the architects of the Olympic Stadium were inspired to mimic this roofing in their “floating” roof design and save the illegal church from been flattened for the sporting event—this all occurred in the seventies, back when stadiums and sporting events at least appeared to have had ethical guidelines regarding local residents.

After tea and an informal talk from the artist, the crowds gather in front of the Peace Church to be led in procession to said stadium. During Anna McCarthy & Gabi Blum’s Parade of the W(e/a)k, a group of colourful protesters descend from a hilltop, many with the word “Nein” emblazoned on their t-shirts. I happen to be walking with a hot-blooded sceptic, who tells me the stadium’s design was an aesthetic coincidence. He tells me the city’s mayor is a member of the “new right” and describes Munich as a place with heavy state policing and surveillance. He relays this as we enter the epic sci-fi-looking stadium, with masked performers handing out flowers and pamphlets.

“The artists become the facilitators for wider discussions; no-one is discussing the material aspect of the works, the aesthetic choices or how effective their conceptual framework is”

I am hustled into another conversation, as we queue for beers, about football hooliganism, the gentrification of stadiums and the social impact of the game. Finally taking our seats, the small crowd of about 150 people watch the eagerly awaited reenactment of the 1974 World Cup match between East Germany and West Germany. The original game was the only direct battle of sorts between the two sides of the then German state—which meant the stakes were high. It was not only a game but a political encounter between two countries that had only recently officially recognized each other. In the 1974 original, the two teams played with determination and fear, this was not just a game, this was about national legacy. They antagonized each other without results for almost the full ninety minutes until West Germany scored one goal in the final moments of the game; a micro victory.

In the 2018 PAM version of the game, the artist Massimo Furlan and the actor Franz Beil both reenact the radio commentary seamlessly until Beil falls to the ground, holding his ankle. The crowd cheer and then begin shouting insults, goading him to get up, keep playing, stop time wasting. Moments go by and Beil doesn’t move, only mouthing something unintelligible over the crowd’s roars—the commentary goes on but the reenactors have lost the plot. Eventually, paramedics turned up on the pitch and Beil is taken away, waving to the crowds with a grin. Furlan plays on alone, pacing the pitch. Moments later a streaker strips at the sideline and runs across the pitch, bare-arsed in the light mist of the rain, followed by security guards—the crowd goes wild, as the very literal act of game-changing is accomplished in our broken concentration. The game continues, and very little happens, but the crowd stay chatting, shouting and drinking.

“Moments later a streaker strips at the sideline and runs across the pitch, bare-arsed in the light mist of the rain”

Overall, I don’t feel that PAM, fail or succeed in their intention of producing “game changers”, but what they do, is introduce chaos theory to an area of life (contemporary art) which is usually based on a determined set of outcomes (the exhibition). This chaos is produced effectively by the sites they have selected, setting most of the works in public spaces, which offers easy chatter between viewers. Hence the stories, responses and actions begin to pass from viewer to viewer, instead of the artists holding all the cards. The artists become the facilitators for wider discussions; no-one discusses the material aspect of the works, the aesthetic choices or how effective their conceptual framework is, but instead they talk about the broader micro and macro shadows they cast on Munich, Germany and humanity as a whole.

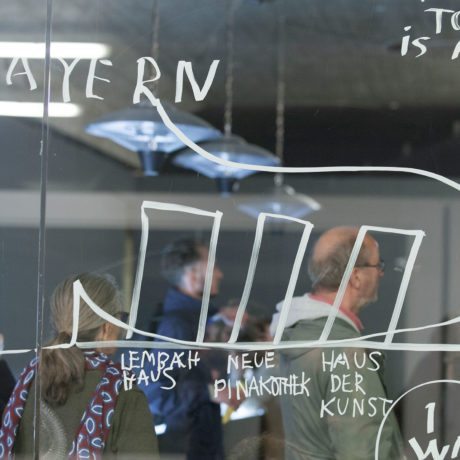

One such artist is Franz Wanner. I meet him over brunch just before Dan Perjovschi’s Live Painting 1 Labor Day. Wanner explains to me how his research led him to uncover four sites used for private covert surveillance that had been set up in Munich to allow the government to spy on its citizens. One of these sites was inside the Frauenkirche, and he broke the news on national radio last week. This has led to the complex question of whether the church worked with the secret service to exploit and abuse the public space it inhabited and violate its congregation’s trust—this has now become a national concern. Wanner explains to me that his artwork has led to a very real form of activism. PAM has perhaps inadvertently enabled him to uncover truths about the city of Munich that cannot be ignored. This is what is truly unique about the programme, Joanna Warsza has enabled a political discussion about public space that in itself is a potentially provocative radical game changer for the future of art and public life—and it’s only the first weekend.

All images © Paul Valentin und Michael Pfitzner. Courtesy the artist and PAM 2018