The first cowboy Jonathan Lyndon Chase met was their own grandmother. She grew up on a farm in Georgia before migrating to the city of Philadelphia when she was 16. When Chase was born in 1989, she became a “third parent” to them, playing an intimate role in their upbringing.

Their grandmother would captivate them with stories of her adventures on the farm, and they spent hours watching Westerns together. She was also a devout member of the Baptist Church. “At times it divided us, as I was figuring myself out as a gay person and grappling with the trauma I went through,” Chase recalls. “But we still bonded deeply on things such as cowboys.”

When Chase’s grandmother passed away, the Philadelphian artist returned to the figure of the cowboy in their memories, in dreams, and in their works. Cowboys became a prominent motif in their depictions of queer Black love and community, riding across canvases in exuberant colours and unruly brushstrokes.

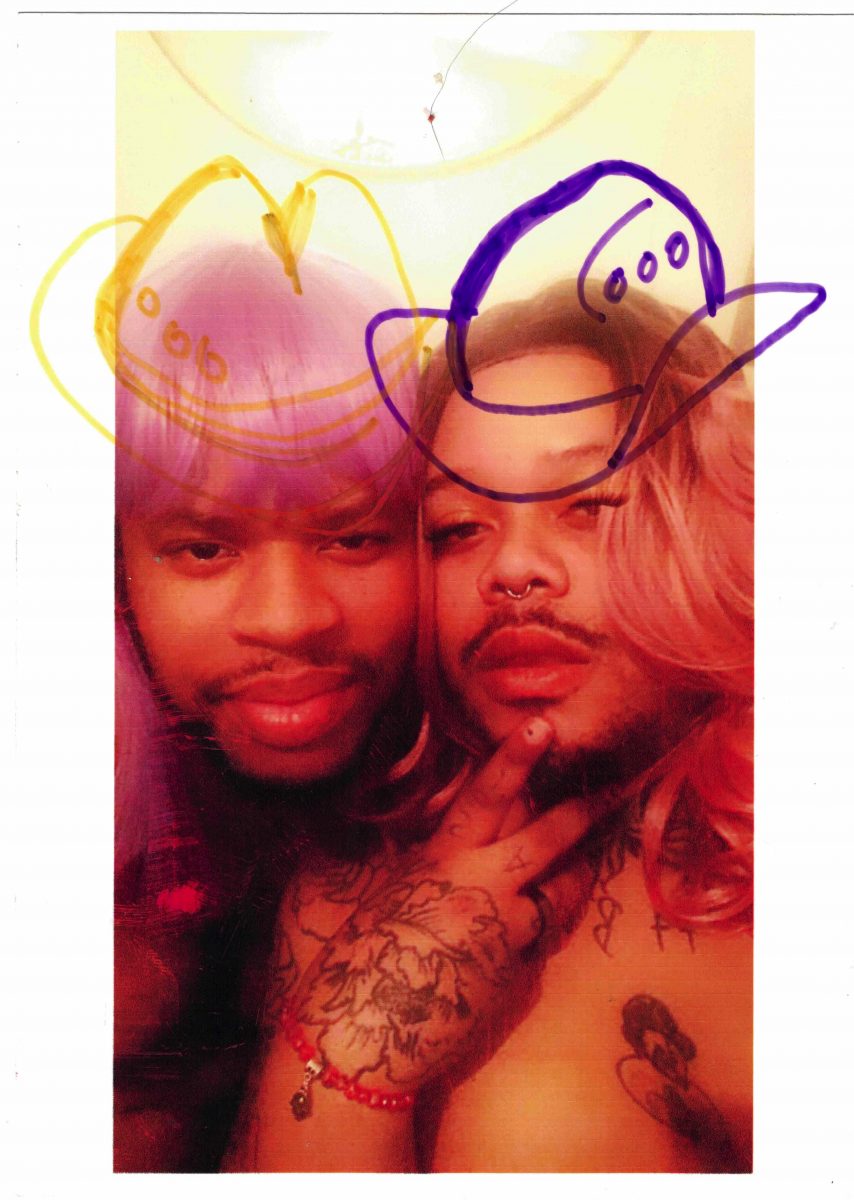

- Both: Jonathan Lyndon Chase, wild wild Wild West/Haunting of the Seahorse, 2020

Out of their grief came Wild Wild Wild West/Haunting of the Seahorse, an experimental two-part book. A “love letter” to their grandmother, where pen and ink drawings of cowboy hats, horseshoes and naked cowboys on horseback swirl among crucifixes, tears, handwritten outpourings, and faded photographs of My Little Pony toys with rainbow manes.

While the figure of the cowboy is a point of healing for Chase, a potent connection to their grandmother, it is also represented as an intersectional space of desire, self-discovery and decolonisation. “Cowboys in American history have predominantly been symbols of beauty and masculinity and have been mostly white and heterosexual,” Chase writes, after listing touchstones of the Western genre: Brokeback Mountain, Bonanza, Gunsmoke and Rifleman.

“Cowboys have been largely depicted in porn as a sex symbol in gay culture,” they continue. “How do we reframe or uncolonise desire and uncolonise beauty?” Intimate and introspective, Wild Wild Wild West confronts received notions of the cowboy as a paragon of all-American masculinity, and contributes to a progressive canon of image-making that remaps the Wild West into a landscape of individual and collective expression.

“From music to fashion, art to cinema, this highly-charged icon of Americana has become a prism through which to refract and rethink identity”

It is a potent symbol for reinvention and has for several years been explored in popular music and fashion with the birth in the late 2010s of the “yeehaw agenda” (a term coined by pop culture archivist Bri Malandro). Propelled by Black artists like Solange and Megan Thee Stallion, this viral movement sought to reclaim country culture and Western aesthetics.

The image of the gay cowboy has also been reframed in recent years, from musician Lil Nas X’s bedazzled cowboy getups to queer Colombian artist Bobby Larson’s Howdy Homo prints of cowgirls. Meanwhile, photographer Luke Gilford

has worked to joyfully document America’s queer rodeo community.

The movement redresses the history of erasure, which has largely removed the one in four cowboys who were Black from popular representation. While there were numerous cattle-raising Native Americans and Mexican vaqueros, Hollywood has for decades whitewashed the cowboy narrative.

This shift has extended to the art world too. In 2016, influential group exhibition Black Cowboy was presented at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Curated by Amanda Hunt, it shed light on African American communities with long histories of keeping and training horses. Among the featured photographs were Brad Trent’s portraits of the Federation of Black Cowboys, Deana Lawson’s serene scenes of shirtless men on horseback in Georgia, and Ron Tarver’s snapshots of Philadelphia’s urban riding clubs.

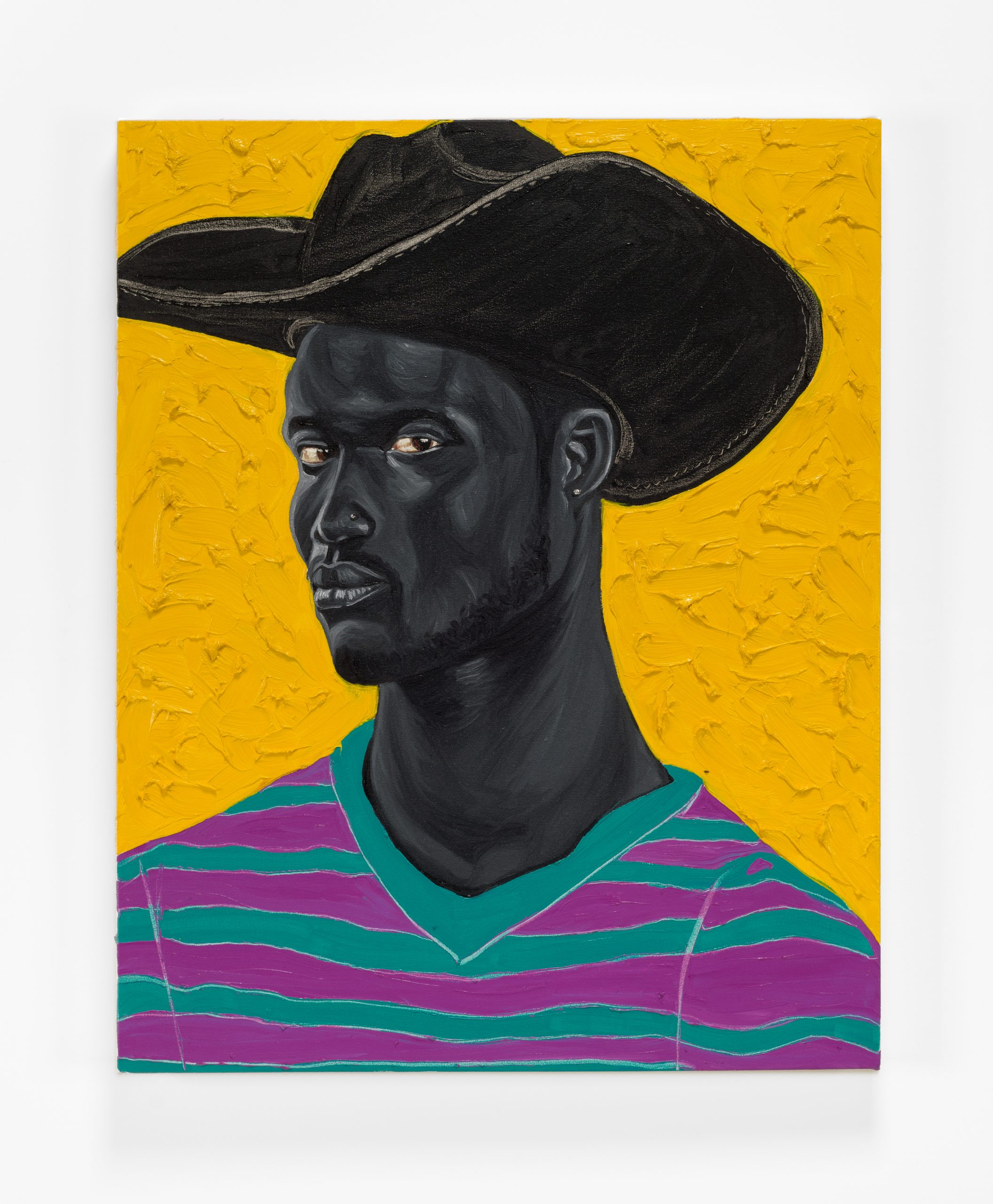

Elsewhere, Portland-based Ghanaian painter Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe creates a new face for this character through his own Black Cowboy project. Painted in vivid, transformative colours, Quaicoe’s majestic portraits of Black cowgirls and cowboys are visions of empowerment and reclamation.

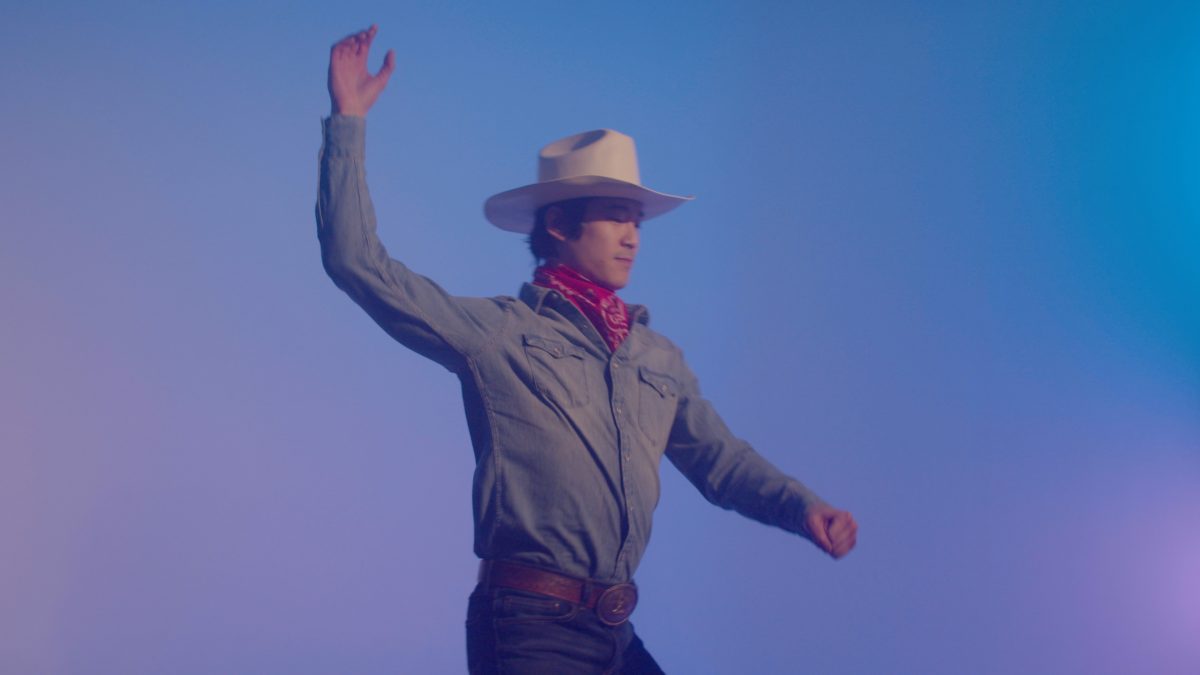

New York artist Kenneth Tam used the archetype of the cowboy as a foil for Asian American masculinity in his 2021 video exhibition Silent Spikes. In the film, he reflects on the intertwined histories of American westward expansion and immigration to the US. Tam’s interest in the cowboy has roots in the movie Westerns his father, who came from Hong Kong, used to watch.

“While there were numerous cattle-raising Native Americans and Mexican vaqueros, Hollywood has for decades whitewashed the cowboy narrative”

“Thinking about my father’s relationship to these images definitely fed into my desire to investigate the character of the cowboy,” Tam says. “And also because it was a cinematic or representational space in which Asian American men were occluded. I wanted to see what would happen if you had them play these characters, how I could complicate that figure, take it to a place that perhaps did not yet exist.”

In his two-channel film, Tam spotlights the labour strike organised by thousands of Chinese Transcontinental Railroad workers in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 1867. Set alongside this narrative are sequences involving five untrained performers of Asian descent. Dressed as cowboys, the men undertake a series of activities, such as imitating the dance-like movements of rodeo riders and riding a creaking mechanical bull.

“The figure of the cowboy is represented as an intersectional space of desire, self-discovery and decolonisation”

Taken out of context, there’s a nakedness to the gyrations and thrusts of the rodeo movements, through which Tam renders vulnerable the masculine figure of the bull rider. The choreography imitates the film’s rhythms more broadly: how it entangles past and present, audio and visual forms, moving away from the idea of the cowboy as an apex to aspire to and exploring the spaces around it and beyond. “The cowboy itself is a figure I’m a bit ambivalent about,” Tam explains. “It’s less about my participants inhabiting that swagger, and more about asking how their identities, histories or their physicality can complicate it.”

Themes of displacement are present in the films that inspired Tam’s project. These include Chloé Zhao’s The Rider (2017), about an injured rodeo rider who loses his sense of purpose, and Lu Chan’s Kekexili: Mountain Patrol (2004), which transposes the conventions of the Western to Tibet.

In Silent Spikes, these influences materialise in the recurring tracking shot of a railroad tunnel. “The cowboy comes with so much meaning, so much baggage,” says Tam. “But this amorphous tunnel is the opposite of that. It hints at the construction of a new kind of masculinity, one that’s perhaps more open-ended and isn’t fully delineated.”

While the cowboy is a point of departure for Tam, rather than an icon to be reclaimed, the artist joins Chase in presenting this highly-charged symbol of Americana as a prism through which to refract and rethink identity. From art to cinema, music to fashion, the cultural plains of the Wild West have begun to offer moments of release, and a place for lost stories to be found.

Madeleine Pollard is a Berlin-based journalist specialising in culture and current affairs