We begin in the garden. Derek Jarman once wrote that the gardener “digs in another time, without past or future, beginning or end… Here is the Amen beyond the prayer”. The garden, then, proposes a new kind of history, one unconstrained by the temporal. The titular work of BingenTV, an exhibition at Mimosa House by the artists and scholars Sophie Seita and Naomi Woo, is a talk show ostensibly about gardening, allegedly shot in 1987 but cancelled due to Thatcher’s infamous Section 28 amendment. Note allegedly, which is key to the work. It is no matter that the show’s original existence cannot be verified, no matter that its footage is suspiciously high-resolution or that I recognise one of the actor’s faces. The nature of BingenTV is speculation, a technique so unnatural to ‘the archive’ but, as Seita and Woo propose, so urgent.

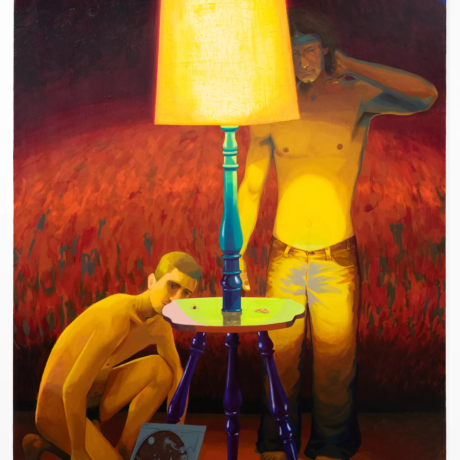

Art galleries are kind of like gardens if you think of art as something living, like a plant. A monumental textile piece hangs floor to ceiling at the entrance of Mimosa House. It reminds me of a tree and reads: “To tend/ to sow/ to grow/ to mend/ to mix/ to teach/ to learn/ to make/ to weed/ to heal/ to sing”. It forms an affirmation with which to proceed into the exhibition. Abandoned to the capricious body fluids of the outdoors– its dirt and elements– we find ourselves in an exquisite disarray, a submission of sorts. Seita calls this radical amateurism, the idea of “experimentation as hugely pleasurable”, for which the garden and the art institution are (quite literally) fertile ground.

BingenTV was conceived alongside The Hildegard von Bingen Society for Gardening Companions, a queer-feminist collective which situates the garden as a haven for an anti-institutional, radical community. The story of its namesake 12th-century saint is not dissimilar to that of the society itself– von Bingen’s contributions to botanical healing, music, proto-surrealist prose and mysticism were unrecognised until the late 20th century. She is now one of the earliest identifiable composers– of eerie chants whose monastic roots have largely been discarded in favour of countless contemporary meditation playlists (perhaps Spotify, like Jarman’s garden, is transcendent of time!)

Seita and Woo are not the first to identify the radical nature of von Bingen’s work. During the late 20th century, she enjoyed a cult-like following amongst New Age spiritualists, as well as the second-wave feminist movement. After all, much of her texts have a contemporary presence– her concept of viriditas (the healing power and verdancy of nature) is particularly exigent. “The air lives in viriditas and in the flowers”, she wrote, “and the waters flow as if alive, and the sun lives within its own light, and when the moon has waned, it is rekindled by the light of the sun and thereby lives anew, and the stars shine forth in their own light as though alive”. When we fight against nature, von Bingen says, we are fighting a losing battle. If only we had listened!

Von Bingen’s sole allusion to the existence of a secret group of women appears in the form of vox inauditae linguae, her ‘unknown’ (i.e. secret) language, which was assumed to have perished with her death. From this initially abstract revelation, encountered by Woo and Seita in 2020, a jigsaw history grew: of poetry, diary entries, and photographs, as well as– most significantly– conversation. Threads of knowledge trace Mary Seacole to Rosa Luxemburg to Adrienne Rich, all suspected members of the society. From the detritus of a pandemic, which spread like rumours of a storm from overseas, forgotten traces of community and shared history were unearthed.

Another quote, this one taken from the wall of the exhibition: “Instead of being clearly available as visible evidence, queerness has existed as innuendo, gossip, fleeting moments” (José Esteban Muñoz). Perhaps, then, gossip can be labelled as a radical practice, particularly since those derided for it (by the patriarchy) are most often marginalised people. Beyond playground politics and she said/he said, the reparative capacity of gossip is evident, exemplified by movements like #MeToo. “Gossip can absolutely be a feminist practice”, Woo affirms. I like to think of it as the radical potential of the unofficial account.

Gossip can also be necessary, particularly for those whose stories are not written into the canonical tomes of history. After all, in order to evidence, the pinnacle of academic exactitude, you must have a presence to evidence from. Both Seita and Woo are familiar with the upper echelons of intellectual rigour, having met whilst studying at Cambridge and forged careers in academia and classical music, respectively, alongside their collaborative art practice. Seita insists that “it’s not so much that we’re not interested in academic rigour at all”, but rather “rigour mixed with intuition, or frivolousness, or silliness, fandom, curiosity, openness, and maybe even frustration or confusion or ambiguity”. It is all of that which does not have a place in a setting striving for unimpeded clarity: a rebellion against the academy’s problematic ‘purity’ of thought.

Like gossip, speculative fiction slips through the gaps, its possibilities informed by the marginalised writers and artists who have led its utilisation as creative methodology. The visual artist Sin Wai Kin, whose solo show Portraits closes at Soft Opening on December 16th, employs the dissolution of binaries through drag culture, dramaturgy and ‘self-historicisation’. The writer Saidiya Hartman calls her work “critical fabulation”, a reparative process in which “the desire and want of something better decide the contours of the telling”. Seita and Woo neither deny nor confirm BingenTV’s fictionality– the film is the consequence, not the crux, of their practice. To the artists, the question of validity is not even important in this context; by refusing to confirm the imagined, BingenTV is forcibly enlisted into the archive. In the end, the questions provoked by the show remain the same. How might global queer and feminist histories have manifested had they not been erased?

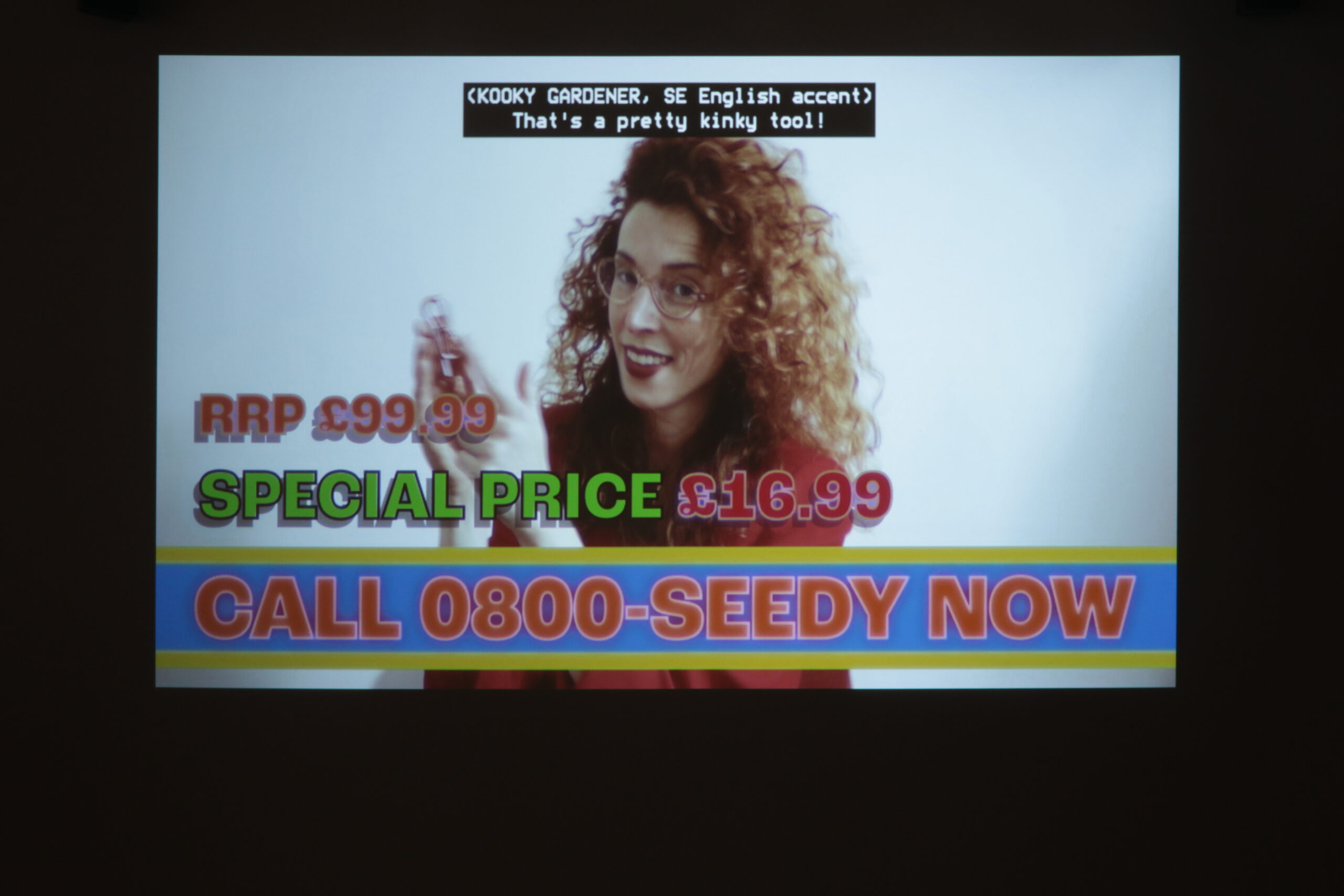

BingenTV’s host, Gardenia, is an effervescent heartthrob who blows kisses at her audience and whirls across her set in lurid blazers and sweetheart candy eyeshadow, an absurd trope of the decade she is depicted in. Episodes are bifurcated by adverts for kinky ‘gardening tools’ and an invocation of von Bingen’s spirit marked by the rubbing of ‘radishes’. It is all quite endearingly nonsensical and totally removed from the reservedness suggested by an oppressed and secret society. In fact, what it really is, is quite funny.

I begin to think: I probably don’t have as much fun in galleries as I ought to. Art institutions can be so serious– you can’t really blame them, as concerned as they are with proving the validity of their commentary. BingenTV proposes that artistic research be as legitimised as that of the academy. I should note– the halls of scholarship are not a heartless place, nor are they a lost cause (there are those who dissemble the canon from the inside). But, as Boris Groys writes in The Fate of Art in the Age of Terror (2005), “art institutions are places where we are reminded of the whole history… so that we can measure our own time against this historical background”. Seita continues: “Even when we were entirely confined to academia, we felt the limitations of what it could offer for the kind of things we wanted to know, or the kind of ways we wanted to express that knowledge”.

What Seita and Woo really wanted was a setting in which they could imbue art and research with love. Derived from Audre Lorde’s mantra of self-care as self-preservation, and, consequently, political warfare, love becomes revolutionary action. I have a bell hooks quote at the top of my notes app: “The word ‘love’ is most often defined as a noun, yet the more astute theorists of love acknowledge that we would all love better if we used it as a verb”. Love as a verb = tending, sowing, healing, growing. Are we still in the gallery or back in the garden? I can’t quite remember.

What fight for justice is not cut through with love? What else fuels our drive to grapple with the insurmountable derangement of war and the world? Empathy, solidarity, even anger– these can all be forms of love, which feels particularly pertinent given the current state of global politics. And, although BingenTV is concerned with the archive, this is– as aforementioned– the kind of history that dispels with the binaries of past, present, and future. What happened then is just as concerned with the now. Love as a verb = love as action, action, action.

As an alternative model to the historical canon, a propagator of the art institution’s reparative potential, and a queer community of care, BingenTV is a pertinent reminder that those qualities which exist most potently outside of the academy– speculation and love– can be more radical than those which exist within it. To finish, a von Bingen quote: “An interpreted world is not a home. Part of the terror is to take back our own listening, to use our own voice, to see our own light.” An interpreted world may not be a home, but a garden is!

Words by Ella Slater

bingenTV is on at Mimosa House from 27 October until 6 December 2023

17 Theobalds Road

London WC1X 8SP